Esther Johnson

Esther Johnson (13 March 1681 – 28 January 1728) was the English friend of Jonathan Swift, known as "Stella". Whether or not she and Swift were secretly married, and if so why the marriage was never made public, remains a subject of intense debate.

Esther Johnson | |

|---|---|

Esther Johnson, from an 1893 publication. | |

| Born | 13 March 1681 |

| Died | 28 January 1728 (aged 46) |

Parentage and early life

She was born in Richmond, Surrey, and spent her early years at Moor Park, Farnham, home of Sir William Temple, 1st Baronet. Here, when she was about eight, she met Swift, who was Temple's secretary: he took a friendly interest in her from the beginning and apparently supervised her education.[1]

Her parentage has been the subject of much speculation. The weight of evidence is that her mother acted as companion to Temple's sister, Lady Giffard, and that both Stella and her mother were regarded as part of the family. Stella's father is said to have been a merchant who died young: gossip that she was Temple's illegitimate daughter seems to rest on nothing more solid than the friendly interest he showed in her (there were similar rumours about his supposed relationship to Swift).[2]

Friendship with Swift

When Swift saw her again in 1696 he considered that she had grown into the "most beautiful, graceful and agreeable young woman in London". Temple at his death in 1699 left her some property in Ireland; it was at Swift's suggestion that she move to Ireland in 1702 to protect her interests, but her long residence there, like Vanessa's, was probably due to a desire to be close to Swift. She generally lived in Swift's house, though always with female companions like Rebecca Dingley, a cousin of Temple whom she had known since childhood.[3] Esther became extremely popular in Dublin and an intellectual circle grew up around her, although it was said that she found the company of other women tedious and only enjoyed the conversation of men.

In 1704 their mutual friend, the Reverend William Tisdall, told Swift that he wished to marry Stella, much to Swift's private disgust, although his letter to Tisdall, which outlined his objections to the marriage, was courteous enough, making the practical point that Tisdall was not in a position to support a wife financially. Little is known about this episode, other than Swift's letter to Tisdall. It is unclear if Tisdall actually proposed to Stella: if he did he seems to have met with a firm rejection, and he married Eleanor Morgan two years later. He and Swift, after a long estrangement, became friends once more after Stella's death.

Vanessa

Stella's friendship with Swift became fraught after 1707 when he met Esther Vanhomrigh, daughter of the Dutch-born Lord Mayor of Dublin. Swift became deeply attached to her and invented for her the name "Vanessa". She in turn became infatuated with him and after his return to Ireland followed him there.[4] The uneasy relationship between the three of them continued until 1723 when Vanessa (who was by now seriously ill from tuberculosis) apparently asked Swift not to see Stella again. This led to a violent quarrel between them, and Vanessa before her death in June 1723 destroyed the will she had made in Swift's favour.[5]

Secret marriage

Whether Swift and Stella were married has always been a subject of intense debate. The marriage ceremony was allegedly performed in 1716 by St George Ashe, Bishop of Clogher (an old friend of Swift, and also his college tutor), with no witnesses present, and it was said that the parties agreed to keep it secret and live apart. Stella always described herself as a "spinster" and Swift always referred to himself as unmarried; Rebecca Dingley, who lived with Stella throughout her years in Ireland, said that Stella and Swift were never alone together. Those who knew the couple best were divided on whether a marriage ever took place: some, like Mrs. Dingley and Swift's housekeeper Mrs. Brent laughed at the idea as "absurd". On the other hand, Thomas Sheridan, one of Swift's oldest friends, believed that the story of the marriage was true: he reportedly gave Stella herself as his source. Historians have been unable to reach a definite conclusion on the truth of the matter: Bishop Ashe died before the story first became public, and there were no other witnesses to the supposed marriage.[6]

Writings

A collection of her witticisms was published by Swift under the titles of "Bon Mots de Stella" as an appendix to some editions of Gulliver's Travels.[7] Journal to Stella, a collection of 65 letters from Swift to Stella, was published posthumously.

Last years and death

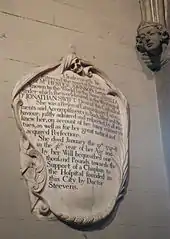

Her health began to fail in her mid-forties. In 1726 she was thought to be dying; Swift rushed back from London to be with her but found her better. The following year it became clear that she was gravely ill. After sinking slowly for months she died on 28 January 1728, and was buried in St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin.[9] Swift was inconsolable at Esther's death and wrote The Death of Mrs. Johnson in tribute to her; when he died he was buried beside her at his own request. A ward in St Patrick's University Hospital is named "Stella" in her memory.

Portrayals

In the 1994 film Words Upon the Window Pane, based on the play by William Butler Yeats, Stella is played by Brid Brennan. The plot turns on a seance in Dublin in the 1920s, where the ghosts of Swift, Stella and Vanessa appear to resume their ancient quarrel.

Publications (fiction)

- The Basilisk of St. James (London, 1945, Chapman and Hall) by Elizabeth Myers, wife of Littleton C. Powys, who was a brother of John Cowper Powys. The novel has as its main protagonist Jonathan Swift. Central to the plot is the personal conflict that arose from Swift's relationships with both Esther Vanhomrigh (Vanessa) and Esther Johnson (Stella).

- Morgan-Cole, Trudy J. The violent friendship of Esther Johnson, Penguin Canada, 2006.(ISBN 978-0-14-301768-4)

- Dean Swift and the Two Esthers by Lyndon Orr 1856 - 1914 from Famous Affinities of History: The Romance of Devotion

References

- Stephen, Leslie (1898). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 55. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 208.

- Stephen p.208

- Stephen pp.208-9

- Stephen p.215

- Stephen p.216

- Stephen pp.216-7

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 23 August 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Casey, Christine (2005). The Buildings of Ireland: Dublin. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 622. ISBN 978-0-300-10923-8.

- Stephen p.219