Essequibo (colony)

Essequibo (Dutch: Kolonie Essequebo)[1][2] was a Dutch colony on the Essequibo River in the Guiana region on the north coast of South America from 1616 to 1814. The colony formed a part of the colonies that are known under the collective name of Dutch Guiana.

Colony of Essequebo Essequebo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1616–1815 | |||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||

Dutch Essequibo in 1800 | |||||||

| Status | Dutch colony | ||||||

| Capital | Fort Kyk-Over-Al (1616 - 1739) Fort Zeelandia (1739 - 1815) | ||||||

| Common languages | Dutch, Skepi Creole Dutch | ||||||

| Governing company | |||||||

• 1616–1815 | Dutch West India Company | ||||||

| Governor | |||||||

• 1616–24 | Adrian Groenewegen | ||||||

• 1796–1802 | Abraham Jacob van Imbijze van Batenburg | ||||||

| History | |||||||

• Established | 1616 | ||||||

• Ceded to the United Kingdom | November 20 1815 | ||||||

| |||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Guyana | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

History

.jpg.webp)

Essequibo was founded by colonists from the first Zeelandic colony, Pomeroon conquered in 1581, which had been destroyed by Spaniards and local warriors around 1596. Led by Joost van der Hooge, the Zeelanders travelled to an island called Kyk-Over-Al in the Essequibo river (actually a side-river called the Mazaruni). This location was chosen because of its strategic location and the trade with the local population. Van der Hooge encountered an older ruined Portuguese fort there (the Portuguese arms had been hewn into the rock above the gate). Using funds of the West Indian Company (WIC), van der Hooge built a new fort called "Fort Ter Hoogen" from 1616 to 1621, though the fort quickly became known amongst the inhabitants as Fort Kyk-Over-Al (English: Fort See-everywhere). The administration of the West Indian Company as well as the governor of the entire colony settled here in 1621.

Initially, the colony was named Nova Zeelandia (New Zeeland), but the usage of the name Essequibo soon became common. On the southern shore of the river the hamlet Cartabo was built, containing 12 to 15 houses. Around the river, plantations were created where slaves cultivated cotton, indigo and cacao. Somewhat further downstream, on Forteiland or "Great Flag Island", Fort Zeelandia was built. From 1624 the area was permanently inhabited and from 1632, together with Pomeroon, it was put under the jurisdiction of the Zeelandic Chamber of the WIC (West Indian Company). In 1657 the region was transferred by the Chamber to the cities of Middelburg, Veere and Vlissingen, who established the "Direction of the New Colony on Isekepe" there. From then on Pomeroon was called 'Nova Zeelandia'.

.jpg.webp)

In 1658, cartographer Cornelis Goliath created a map of the colony and made plans to build a city there called "New Middelburg", but the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665 – 67) put an end to these plans. Essequibo was occupied by the British in 1665 (along with all other Dutch colonies in the Guianas), and then plundered by the French. The following years the Zeelanders sent a squadron of ships to retake the area. While the Suriname colony was captured from the British by Abraham Crijnssen, the by then abandoned Essequibo was occupied by Matthys Bergenaar. In 1670 the Chamber of the WIC in Zeeland took over control of the colonies again. The Dutch colonies in the region endured much suffering as a result of the Nine Years' War (1688 – 97) and the Spanish Succession War (1701 – 14), which brought pirates into the region. In 1689 Pomeroon was destroyed by French pirates, and abandoned.

The Chamber of the WIC in Zeeland kept control over the colonies, which sometimes led to criticism from The Chamber of the WIC in Amsterdam, who also wanted to start plantation there. The Zeelanders however, had established the colony by themselves, and after they retook possession of Essequibo under command of the commander of Fort Nassau Bergen in 1666, they considered themselves as rightful rulers of the region. Under governor Laurens Storm van 's Gravesande, English planters started coming to the colony after 1740.

After 1745, the number of plantations along the Demerara and her side-rivers rapidly increased. Particularly, British colonists from Barbados began settling here. After 1750 a commander of the British population was assigned, giving them their own representation. Around 1780 a small central settlement was established at the mouth of the Demerara, which received the name Stabroek in 1784, named after one of the directors of the West Indian Company.

A group of British privateers captured Essequibo and Demerara on 24 February 1781, but did not stay. In March, two sloops of a Royal Navy squadron under Admiral Lord Rodney accepted the surrender of "Colony of Demarary and the River Essequebo".[3] From 27 February 1782 to February 1783 the French occupied the colony after compelling Governor Robert Kinston to surrender. The peace of Paris, which occurred in 1783 restored these territories to the Dutch.[4]

In 1796 it was permanently occupied by the British and by 1800, Essequibo and Demerara collectively held around 380 sugarcane plantations.

Border disputes

At the Peace of Amiens (1802), the Netherlands received the Essequibo colony for a short time, from 1802 to 1803, but after that the British again occupied it during the Napoleonic Wars. In 1812 Stabroek was renamed by the British as Georgetown. Essequibo became official British territory on 13 August 1814 as part of the Treaty of London and was merged with the colony of Demerara.

But it also became involved in one of Latin America's most persistent border disputes because the new colony had the Essequibo river as its west border with the Spanish Captaincy General of Venezuela. Although Spain still claimed the region, the Spanish did not contest the treaty because they were preoccupied with their own colonies' struggles for independence. On 21 July 1831, Demerara-Essequibo was united with Berbice to create British Guiana with the Essequibo River as its west border, although many British settlers lived west of the Essequibo.

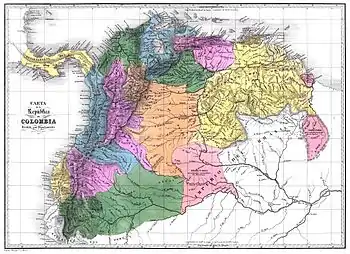

In 1835 the British government asked German explorer Robert Hermann Schomburgk to map British Guiana and mark its boundaries. As ordered by the British authorities, Schomburgk began British Guiana's western boundary with the new Republic of Venezuela at the mouths of the Orinoco River, although all the Venezuelan maps showed the Essequibo river as the east border of the country. A map of the British colony was published in 1840. Venezuela did not accept the Schomburgk Line, which placed the entire Cuyuni River basin within the colony. Venezuela protested, claiming the entire area west of the Essequibo River. Negotiations between Britain and Venezuela over the boundary began, but the two nations could reach no compromise. In 1838, Essequibo was made one of the three counties of Guiana, the other two being Berbice and Demerara.[5] In 1850 both countries agreed not to occupy the disputed zone.

The discovery of gold in the contested area in the late 1850s reignited the dispute. British settlers moved into the region and the British Guiana Mining Company was formed to mine the deposits. Over the years, Venezuela made repeated protests and proposed arbitration, but the British government was uninterested. Venezuela finally broke diplomatic relations with Britain in 1887 and appealed to the United States for help. The British prime minister Lord Salisbury at first rebuffed the United States government's suggestion of arbitration, but when President Grover Cleveland threatened to intervene according to the Monroe Doctrine, Britain agreed to let an international tribunal arbitrate the boundary in 1897.

For two years, the tribunal consisting of two Britons, two Americans, and a Russian studied the case in Paris (France). Their three-to-two decision, handed down in 1899, awarded 94 percent of the disputed territory to British Guiana. Venezuela received only the mouths of the Orinoco River and a short stretch of the Atlantic coastline just to the east. Although Venezuela was unhappy with the decision, a commission surveyed a new border in accordance with the award, and both sides accepted the boundary in 1905. The issue was considered settled for the next half-century.

In 1958, the county of Essequibo was abolished when Guiana was subdivided into districts. Currently, historical Essequibo is part of a number of Guyanese administrative regions and the name is preserved in the regions of Essequibo Islands-West Demerara and Upper Takutu-Upper Essequibo.[5]

On 1962, under UN policy of decolonization, Venezuela renewed its 19th-century claim, alleging that the arbitral award was invalid. In 1949, the US jurist Otto Schoenrich, a named partner in the New York law firm Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt & Mosle, gave the Venezuelan government a memorandum written by Severo Mallet-Prevost, the Official Secretary of the US–Venezuela delegation in the Tribunal of Arbitration, which was written in 1944 to be published only after his death. Mallet-Prevost surmised from the private behavior of the judges that there had a political deal between Russia and Britain,[6] and said that the Russian chair of the panel, Friedrich Martens, had visited Britain with the two British arbitrators in the summer of 1899, and subsequently had offered the two American judges a choice between accepting a unanimous award along the lines ultimately agreed, or a 3 to 2 majority opinion even more favourable to the British. The alternative would have followed the Schomburgk Line entirely, and given the mouth of the Orinoco to the British. Mallet-Prevost said that the American judges and Venezuelan counsel were disgusted at the situation and considered the 3 to 2 option with a strongly worded minority opinion, but ultimately went along with Martens to avoid depriving Venezuela of even more territory.[6] This memorandum provided a motive for Venezuela's contentions that there had in fact been a political deal between the British judges and the Russian judge at the Arbitral Tribunal, and led to Venezuela's revival of its claim to the disputed territory.[7][8] The British Government rejected this claim, asserting the validity of the 1899 award. The British Guiana Government, then under the leadership of the PPP, also strongly rejected this claim. Efforts by all the parties to resolve the matter on the eve of Guyana's independence in 1966 failed. As of today the dispute remains unresolved.

Governors of Essequibo

- Adrian Groenewegen (1616 – 24)

- Jacob Conijn (1624 – 27)

- Jan van der Goes (1627 – 38)

- Cornelis Pieterszoon Hose (1638 – 41)

- Andriaen van der Woestijne (1641 – 44)

- Andriaen Janszoon (1644 – 16..)

- Aert Adriaenszoon Groenewegel (1657 – 64)

- John Scott (1665 – 66)

- Abraham Crijnssen (1666)

- Adriaen Groenewegel (1666)

- Baerland (1667–70)

- Hendrik Bol (1670 – 76)

- Jacob Hars (1676 – 78)

- Abraham Beekman (1678 – 90)

- Samuel Beekman (2 November 1690 – 10 December 1707)

- Peter van der Heyden Resen (10 December 1707 – 24 July 1719)

- Laurens de Heere (24 July 1719 – 12 October 1729)

- Hermanus Gelskerke (d. 1742) (12 October 1729 – April 1742)

- Laurens Storm van 's Gravesande (d. 1775) (April 1743 – 50)[9]

- Robert Nicholson (27 February 1781 – 82)

- Abraham Jacob van Imbijze van Batenburg (22 April 1796 – 27 March 1802)

Commanders of Essequibo

- Albert Siraut des Touches (1784)

- Johannes Cornelis Bert (1784 – 87)

- Albertus Backer (1st time) (1787 – 89)

- Gustaaf Eduard Meijerhelm (1789 – 91)

- Matthijs Thierens (1791 – 93)

- Albertus Backer (2nd time) (1793 – 22 April 1796)

- George Hendrik Trotz (27 March 1802 – September 1803)

Directors-general

- Laurens Storm van 's Gravesande (1752 – 2 November 1772)[9]

- George Hendrik Trotz (2 November 1772 – 81)

Notes

- Luttenberg, G. (1840). Register der wetten en besluiten: betrekkelijk het openbaar bestuur in de Nederlanden,over het tijdvak van 1796 tot en met 1839 : nwe verm. en verb. uitg (in Dutch). Doijer.

- Kampen, Nicolaas Godfried van (1832). Geschiedenis der Nederlanders buiten Europa, of verhaal van de togten, ontdekkingen, oorlogen, veroveringen en inrigtingen der Nederlanders in Azië, Afrika, Amerika en Australië, van het laatste der zestiende eeuw tot op dezen tijd (in Dutch). Erven François Bohn.

- "No. 12181". The London Gazette. 21 April 1781. p. 1.

- Henry (1855), p.239.

- Regions of Guyana at Statoids.com. Updated 20 June 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- Schoenrich, Otto, "The Venezuela-British Guiana Boundary Dispute", July 1949, American Journal of International Law. Vol. 43, No. 3. p. 523. Washington, DC. (USA).

- Isidro Morales Paúl, Análisis Crítico del Problema Fronterizo "Venezuela-Gran Bretaña", in La Reclamación Venezolana sobre la Guayana Esequiba, Biblioteca de la Academia de Ciencias Económicas y Sociales. Caracas, 2000, p. 200.

- de Rituerto, Ricardo M. Venezuela reanuda su reclamación sobre el Esequibo, El País, Madrid, 1982.

- P.J. Blok & P.C. Molhuysen (1927). "Nieuw Nederlandsch biografisch woordenboek. Deel 7". Digital Library for Dutch Literature (in Dutch). Retrieved 14 August 2020.

References

- Henry, Dalton G. (1855) The History of British Guiana: Comprising a General Description of the Colony: A narrative of some of the principal events from the earliest period of products and natural history.

- Paasman, A.N., (1984) Reinhart: Nederlandse literatuur en slavernij ten tijde van de Verlichting, 4.1: Korte geschiedenis van de kolonie Guiana