Epistolary novel

An epistolary novel is a novel written as a series of documents. The usual form is letters,[1] although diary entries, newspaper clippings and other documents are sometimes used. Recently, electronic "documents" such as recordings and radio, blogs, and e-mails have also come into use. The word epistolary is derived from Latin from the Greek word ἐπιστολή epistolē, meaning a letter (see epistle).

The epistolary form can add greater realism to a story, because it mimics the workings of real life. It is thus able to demonstrate differing points of view without recourse to the device of an omniscient narrator. An important strategic device in the epistolary novel for creating the impression of authenticity of the letters is the fictional editor.[2]

Early works

There are two theories on the genesis of the epistolary novel. The first claims that the genre is originated from novels with inserted letters, in which the portion containing the third person narrative in between the letters was gradually reduced.[3] The other theory claims that the epistolary novel arose from miscellanies of letters and poetry: some of the letters were tied together into a (mostly amorous) plot.[4] Both claims have some validity. The first truly epistolary novel, the Spanish "Prison of Love" (Cárcel de amor) (c.1485) by Diego de San Pedro, belongs to a tradition of novels in which a large number of inserted letters already dominated the narrative. Other well-known examples of early epistolary novels are closely related to the tradition of letter-books and miscellanies of letters. Within the successive editions of Edmé Boursault's Letters of Respect, Gratitude and Love (Lettres de respect, d'obligation et d'amour) (1669), a group of letters written to a girl named Babet were expanded and became more and more distinct from the other letters, until it formed a small epistolary novel entitled Letters to Babet (Lettres à Babet). The immensely famous Letters of a Portuguese Nun (Lettres portugaises) (1669) generally attributed to Gabriel-Joseph de La Vergne, comte de Guilleragues, though a small minority still regard Marianna Alcoforado as the author, is claimed to be intended to be part of a miscellany of Guilleragues prose and poetry.[5] The founder of the epistolary novel in English is said by many to be James Howell (1594–1666) with "Familiar Letters" (1645–50), who writes of prison, foreign adventure, and the love of women.

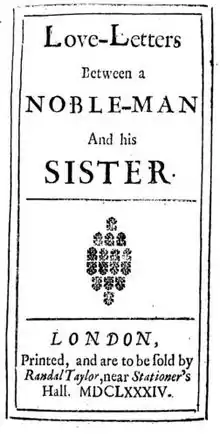

The first novel to expose the complex play that the genre allows was Aphra Behn's Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister, which appeared in three volumes in 1684, 1685, and 1687. The novel shows the genre's results of changing perspectives: individual points were presented by the individual characters, and the central voice of the author and moral evaluation disappeared (at least in the first volume; her further volumes introduced a narrator). Behn furthermore explored a realm of intrigue with letters that fall into the wrong hands, faked letters, letters withheld by protagonists, and even more complex interaction.

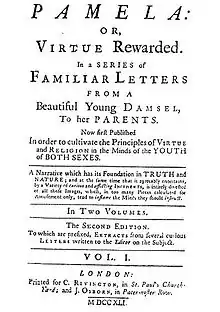

The epistolary novel as a genre became popular in the 18th century in the works of such authors as Samuel Richardson, with his immensely successful novels Pamela (1740) and Clarissa (1749). John Cleland's early erotic novel Fanny Hill (1748) is written as a series of letters from the titular character to an unnamed recipient. In France, there was Lettres persanes (1721) by Montesquieu, followed by Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse (1761) by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Choderlos de Laclos' Les Liaisons dangereuses (1782), which used the epistolary form to great dramatic effect, because the sequence of events was not always related directly or explicitly. In Germany, there was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) (1774) and Friedrich Hölderlin's Hyperion. The first Canadian novel, The History of Emily Montague (1769) by Frances Brooke,[6] and twenty years later the first American novel, The Power of Sympathy (1789) by William Hill Brown,[7] were both written in epistolary form.

Starting in the 18th century, the epistolary form was subject to much ridicule, resulting in a number of savage burlesques. The most notable example of these was Henry Fielding's Shamela (1741), written as a parody of Pamela. In it, the female narrator can be found wielding a pen and scribbling her diary entries under the most dramatic and unlikely of circumstances. Oliver Goldsmith used the form to satirical effect in The Citizen of the World, subtitled "Letters from a Chinese Philosopher Residing in London to his Friends in the East" (1760–61). So did the diarist Fanny Burney in a successful comic first novel, Evelina (1788).

The epistolary novel slowly fell out of use in the late 18th century. Although Jane Austen tried her hand at the epistolary in juvenile writings and her novella Lady Susan (1794), she abandoned this structure for her later work. It is thought that her lost novel First Impressions, which was redrafted to become Pride and Prejudice, may have been epistolary: Pride and Prejudice contains an unusual number of letters quoted in full and some play a critical role in the plot.

The epistolary form nonetheless saw continued use, surviving in exceptions or in fragments in nineteenth-century novels. In Honoré de Balzac's novel Letters of Two Brides, two women who became friends during their education at a convent correspond over a 17-year period, exchanging letters describing their lives. Mary Shelley employs the epistolary form in her novel Frankenstein (1818). Shelley uses the letters as one of a variety of framing devices, as the story is presented through the letters of a sea captain and scientific explorer attempting to reach the north pole who encounters Victor Frankenstein and records the dying man's narrative and confessions. Published in 1848, Anne Brontë's novel The Tenant of Wildfell Hall is framed as a retrospective letter from one of the main heroes to his friend and brother-in-law with the diary of the eponymous tenant inside it. In the late 19th century, Bram Stoker released one of the most widely recognized and successful novels in the epistolary form to date, Dracula. Printed in 1897, the novel is compiled entirely of letters, diary entries, newspaper clippings, telegrams, doctor's notes, ship's logs, and the like.

Types

Epistolary novels can be categorized based on the number of people whose letters are included. This gives three types of epistolary novels: monologic (giving the letters of only one character, like Letters of a Portuguese Nun and The Sorrows of Young Werther), dialogic (giving the letters of two characters, like Mme Marie Jeanne Riccoboni's Letters of Fanni Butler (1757), and polylogic (with three or more letter-writing characters, such as in Bram Stoker's Dracula). A crucial element in polylogic epistolary novels like Clarissa and Dangerous Liaisons is the dramatic device of 'discrepant awareness': the simultaneous but separate correspondences of the heroines and the villains creating dramatic tension.

Notable works

The epistolary novel form has continued to be used after the eighteenth century.

Eighteenth century

- Les Liaisons dangereuses is a 1782 French novel by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, about the Marquise de Merteuil and the Vicomte de Valmont, two narcissistic rivals (and ex-lovers) who use seduction as a weapon to socially control and exploit others, all the while enjoying their cruel games and boasting about their talent for manipulation (also seen as depicting the corruption and depravity of the French nobility shortly before the French Revolution). The book is composed entirely of letters written by the various characters to each other.

Nineteenth century

- Fyodor Dostoevsky used the epistolary format for his first novel, Poor Folk (1846), as a series of letters between two friends, struggling to cope with their impoverished circumstances and life in pre-revolution Russia.

- The Moonstone (1868) by Wilkie Collins uses a collection of various documents to construct a detective novel in English. In the second piece, a character explains that he is writing his portion because another had observed to him that the events surrounding the disappearance of the eponymous diamond might reflect poorly on the family, if misunderstood, and therefore he was collecting the true story. This is an unusual element, as most epistolary novels present the documents without questions about how they were gathered. He also used the form previously in The Woman in White (1859).

- Spanish foreign minister Juan Valera's Pepita Jimenez (1874) is written in three sections, the first and third being a series of letters, the middle part narrated by an unknown observer.

- Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897) uses not only letters and diaries, but also dictation cylinders and newspaper accounts.[8]

Twentieth century

- Dorothy L. Sayers and Robert Eustace's The Documents in the Case (1930).

- Haki Stërmilli's novel If I Were a Boy (1936) is written in the form of diary entries documenting the life of the protagonist.

- Kathrine Taylor's Address Unknown (1938) is an anti-Nazi novel in which the final letter is returned marked "Address Unknown", indicating the disappearance of the German character.

- Virginia Woolf used the epistolary form for her feminist essay Three Guineas (1938).

- C. S. Lewis used the epistolary form for The Screwtape Letters (1942), and considered writing a companion novel from an angel's point of view—though he never did so. It is less generally realized that his Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer (1964) is a similar exercise, exploring theological questions through correspondence addressed to a fictional recipient, "Malcolm", though this work may be considered a "novel" only loosely in that developments in Malcolm's personal life gradually come to light and impact the discussion.

- Thornton Wilder's fifth novel Ides of March (1948) consists of letters and documents illuminating the last days of the Roman Republic.

- Theodore Sturgeon's short novel Some of Your Blood (1961) consists of letters and case-notes relating to the psychiatric treatment of a non-supernatural vampire.

- Saul Bellow's novel Herzog (1964) is largely written in letter format. These are both real and imagined letters, written by the protagonist Moses Herzog to family members, friends, and celebrities.

- Up the Down Staircase is a novel written by Bel Kaufman, published in 1965, which spent 64 weeks on the New York Times Best Seller list. In 1967 it was released as a movie starring Patrick Bedford, Sandy Dennis and Eileen Heckart.

- Shūsaku Endō's novel Silence (1966) is an example of the epistolary form, half of which consists of letters from Rodrigues, the other half either in the third person or in letters from other persons.

- Daniel Keyes's short story and novel Flowers for Algernon (1959, 1966) takes the form of a series of lab progress reports written by the main character as his treatment progresses, with his writing style changing correspondingly.

- The Anderson Tapes (1969, 1970) by Lawrence Sanders is a novel primarily consisting of transcripts of tape recordings.

- 84, Charing Cross Road (1970, 1990) by Helene Hanff is the correspondence between Helene Hanff, a freelance writer living in New York City, and a used-book dealer working in London at Marks & Co.

- Stephen King's novel Carrie (1974) is written in an epistolary structure through newspaper clippings, magazine articles, letters, and book excerpts.

- Stephen King also used the epistolary style in his short story "Jerusalem's Lot", a prequel to his novel 'Salem's Lot that was first published in the collection Night Shift.

- In John Barth's epistolary work Letters (1979), the author interacts with characters from his other novels.

- Alice Walker employed the epistolary form in The Color Purple (1982).[9] The 1985 film adaptation echoes the form by incorporating into the script some of the novel's letters, which the actors deliver as monologues.

- Octavia Butler's speculative fiction novels Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998) are predominantly written as journal entries by the main character and protagonist, Lauren Olamina.

- The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13¾ (1982) by Sue Townsend is a comic novel in the form of a diary set in 1980s Britain.

- John Updike's S. (1988) is an epistolary novel consisting of the heroine's letters and transcribed audio recordings.

- Patricia Wrede and Caroline Stevermer's Sorcery and Cecelia (1988) is an epistolary fantasy novel in a Regency setting from the first-person perspectives of cousins Kate and Cecelia, who recount their adventures in magic and polite society. Unusually for modern fiction, it is written using the style of the letter game.

- Avi's young-adult novel Nothing But the Truth (1991) uses only documents, letters, and scripts.

- Bridget Jones's Diary (1996) by Helen Fielding is written in the form of a personal diary.

- Last Days of Summer (1998) by Steve Kluger is written in a series of letters, telegrams, therapy transcripts, newspaper clippings, and baseball box scores.

- The Perks of Being a Wallflower (1999) was written by Stephen Chbosky in the form of letters from an anonymous character to a secret role model of sorts.[10]

Twenty-first century

- The Whalestoe Letters (2000) by Mark Z. Danielewski is an epistolary novella and a companion piece to his debut novel House of Leaves. It is written with letters from the protagonist's mother who lives in a mental institution.

- Richard B. Wright's Clara Callan (2001) uses letters and journal entries to weave the story of a middle-aged woman in the 1930s.

- The Princess Diaries by Meg Cabot is a series of ten novels written in the form of diary entries. Cabot as also used the epistolary form in The Boy Next Door (2002), a romantic comedy novel consisting entirely of e-mails sent among the characters.

- Several of Gene Wolfe's novels are written in the forms of diaries, letters, or memoirs.

- Mark Dunn's Ella Minnow Pea (2001) is a progressively lipogrammatic epistolary novel – the letters become increasingly more difficult to read as the lipogrammatic constraints are brought in, and this requires the reader to attempt to interpret what is being written.

- La silla del águila ("The Eagle's Throne") by Carlos Fuentes (2003) is a political satire written as a series of letters between persons in high levels of the Mexican government in 2020. The epistolary format is treated by the author as a consequence of necessity: the United States impedes all telecommunications in Mexico as a retaliatory measure, leaving letters and smoke signals as the only possible methods of communication, particularly ironic given one character's observation that "Mexican politicians put nothing in writing."

- We Need to Talk About Kevin (2003) is a monologic epistolary novel written as a series of letters from Eva, Kevin's mother, to her husband Franklin.[11]

- The 2004 novel Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell tells a story in several time periods in a nested format, with some sections told in epistolary style, including an interview, journal entries and a series of letters.

- Griffin and Sabine by artist Nick Bantock is a love story written as a series of hand-painted postcards and letters.

- Where Rainbows End (alternately titled "Rosie Dunne" or "Love, Rosie" in the United States) (2004), by Cecelia Ahern, is written in the form of letters, e-mails, instant messages, newspaper articles, etc.

- Uncommon Valour (2005) by John Stevens, the story of two naval officers in 1779, is primarily written in the form of diary and log extracts.

- World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War (2006), by Max Brooks, is a series of interviews from various survivors of a zombie apocalypse.

- Diary of a Wimpy Kid (2007), by Jeff Kinney, is a series of fiction books written in the form a diary, including hand-written notes and cartoon drawings.

- The White Tiger (2008) by Aravind Adiga, winner of the 40th Man Booker Prize in 2008, is a novel in the form of letters written by an Indian villager to the Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao.

- The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society (2008), by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows, is written as a series of letters and telegraphs sent and received by the protagonist.

- A Visit from the Goon Squad (2010) by Jennifer Egan has parts which are epistolary in nature.

- Super Sad True Love Story (2010) by Gary Shteyngart.

- Why We Broke Up (2011) by Daniel Handler, illustrated by Maira Kalman.

- The Martian, by Andy Weir, is written as a collection of video journal entries for each Martian day (sol) by the protagonist on Mars, and sometimes by main characters on Earth and on the space station Hermes.

- The Sacred Diary of Adrian Plass Aged 373⁄4 is one of a series of books written by Adrian Plass, this one consisting entirely of diary entries. Another consists of transcripts of tapes, yet another consists of letters.[12]

- Illuminae, by Jay Kristoff and Amie Kaufmann, is told exclusively through a series of classified documents, censored emails, interviews, and others.

See also

Footnotes

- 11 Epistolary Novels That'll Make You Miss The Days of Letter Writing - Bustle

- A. Takeda. Die Erfindung des Anderen: Zur Genese des fiktionalen Herausgebers im Briefroman des 18. Jahrhunderts. Würzburg, 2008; U. Wirth. Die Geburt des Autors aus dem Geist der Herausgeberfiktion. Editoriale Rahmung im Roman um 1800. Munich, 2008.

- E.Th. Voss. Erzählprobleme des Briefromans, dargestellt an vier Beispielen des 18. Jahrhunderts. Bonn, 1960.

- B.A. Bray. L'art de la lettre amoureuse: des manuels aux romans (1550-1700). La Haye/Paris, 1967

- G. de Guilleragues. Lettres portugaises, Valentins et autres oeuvres. Paris, 1962

- "Treasures of the Library: The History of Emily Montague by Frances Brooke, 1769". Library of Parliament. Parliament of Canada. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- Piepenbring, Dan (21 January 2015). "The First American Novel". The Paris Review. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- 11 Epistolary Novels That'll Make You Miss The Days of Letter Writing - Bustle

- Top 10 modern epistolary novels|Books|The Guardian

- 11 Epistolary Novels That'll Make You Miss The Days of Letter Writing - Bustle

- Top 10 modern epistolary novels|Books|The Guardian

- 100 Must-Read Epistolary Novels from the Past and Present - Book Riot

External links

- BBC Radio 4's 15 March 2007 edition of In Our Times, "Epistolary Literature". Hosted by Melvyn Bragg.