Epidemiology of breast cancer

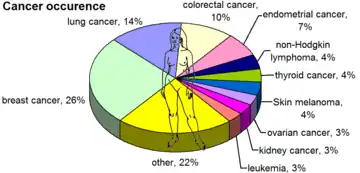

Worldwide, breast cancer is the most common invasive cancer in women. (The most common form of cancer is non-invasive non-melanoma skin cancer; non-invasive cancers are generally easily cured, cause very few deaths, and are routinely excluded from cancer statistics.) Breast cancer comprises 22.9% of invasive cancers in women[2] and 16% of all female cancers.[3]

|

no data

<2

2-4

4-6

6-8

|

8-10

10-12

12-14

14-16

16-18

|

18-20

20-22

>22

|

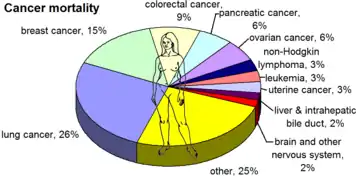

In 2008, breast cancer caused 458,503 deaths worldwide (13.7% of cancer deaths in women and 6.0% of all cancer deaths for men and women together).[2] Lung cancer, the second most common cause of cancer-related death in women, caused 12.8% of cancer deaths in women (18.2% of all cancer deaths for men and women together).[2]

The number of cases worldwide has significantly increased since the 1970s, a phenomenon partly attributed to the modern lifestyles.[4][5]

By age group

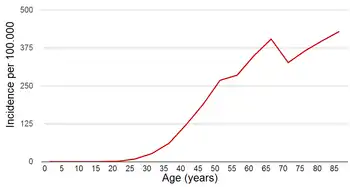

Breast cancer is strongly related to age, with only 5% of all breast cancers occurring in women under 40 years old.[6]

By region

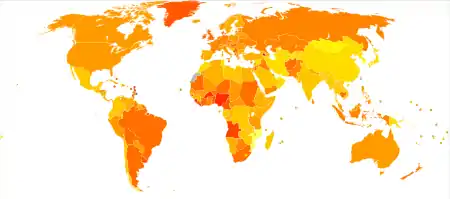

The incidence of breast cancer varies greatly around the world: it is lowest in less-developed countries and greatest in the more-developed countries.[7] In the twelve world regions, the annual age-standardized incidence rates per 100,000 women are as follows: in Eastern Asia, 18; South Central Asia, 22; sub-Saharan Africa, 22; South-Eastern Asia, 26; North Africa and Western Asia, 28; South and Central America, 42; Eastern Europe, 49; Southern Europe, 56; Northern Europe, 73; Oceania, 74; Western Europe, 78; and in North America, 90.[8]

United States

The lifetime risk for breast cancer in the United States is usually given as about 1 in 8 (12%) of women by age 95, with a 1 in 35 (3%) chance of dying from breast cancer.[10] This calculation assumes that all women live to at least age 95, except for those who die from breast cancer before age 95.[11] Recent work, using real-world numbers, indicate that the actual risk is probably less than half the theoretical risk.[12]

The United States has the highest annual incidence rates of breast cancer in the world; 128.6 per 100,000 in whites and 112.6 per 100,000 among African Americans.[10][13] It is the second-most common cancer (after skin cancer) and the second-most common cause of cancer death (after lung cancer) in women.[10] In 2007, breast cancer was expected to cause 40,910 deaths in the US (7% of cancer deaths; almost 2% of all deaths).[14] This figure includes 450-500 annual deaths among men out of 2000 cancer cases.[15]

In the US, both incidence and death rates for breast cancer have been declining in the last few years.[14][16] In the US, the age-adjusted incidence of breast cancer per 100,000 women rose from around 102 cases per year in the 1970s to around 141 in the late 1990s, and has since fallen, holding steady around 125 since 2003. Age-adjusted deaths from breast cancer per 100,000 women rose slightly from 31.4 in 1975 to 33.2 in 1989 and have declined steadily since, to 20.5 in 2014.[17] Nevertheless, a US study conducted in 2005 indicated that breast cancer remains the most feared disease,[18] even though heart disease is a much more common cause of death among women.[19] Studies suggest that women overestimate their risk of breast cancer.[20]

UK

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in the UK (around 49,900 women and 350 men were diagnosed with the disease in 2011), and it is the third most common cause of cancer death (around 11,600 women and 75 men died in 2012).[22] The age-standardised incidence rate of breast cancer is 113.4 per 100,000 populations in Wales and there has been a significant increase in the incidence of breast cancer in Wales over the last three decades, which is likely to be partly due to the introduction of the National Health Service Breast Screening Programme.[23]

Developing countries

"Breast cancer in less developed countries, such as those in South America, is a major public health issue. It is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women in countries such as Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil. The expected numbers of new cases and deaths due to breast cancer in South America for the year 2001 are approximately 70,000 and 30,000, respectively."[24] However, because of a lack of funding and resources, treatment is not always available to those suffering with breast cancer. It has also been shown that while the overall incidence of breast cancer appears to be higher in Caucasian women, black African women tend to present at a younger age and with a more aggressive disease pattern, a pattern that has also been reported among black women born and bred in London suggesting a more genetic link rather than only an environmental cause or late presentation.[25]

Incidence and Mortality

Data on breast cancer in Sub Saharan Africa is available, though extremely limited compared to developed countries.[26] Breast cancer has the highest incidence among Sub Saharan African women, and has now also the highest mortality rate in many of the countries in the region, before cervical cancer.[27] Breast cancer causes 20% of cancer deaths in women and represents 25% of cancers diagnosed.[27] Incidence rates of breast cancer varies from region to region in Sub Saharan Africa and are 30.4, 26.8, 38.6 and 38.9 respectively in Eastern Africa, Central Africa, Western Africa and Southern Africa.[28] Sub Saharan Africa has lower incidence rates for breast cancer than developed countries but the mortality rates reflected in the region are much higher.[27][29] Many reasons were found to be the source of this disparity, including the fact that breast cancer is diagnosed at later stages in Sub Saharan Africa.[29] For example, while Central Africa had a mortality/incidence ratio of 0.55 in 2012, the US had only 0.16.[26] In addition to being diagnosed at later stages, breast cancer in Sub Saharan Africa was also found to have an earlier onset compared to western countries.[27] Screening is considered an important tool to tackle the late stage diagnosis of breast cancer by most policy makers in African Countries, especially given that treatment is greatly limited by the lack of resources.[26][30] More research is also required to produce more updated data on breast cancer and better understand the variances there and how they affect the burden of the disease in the region.[26][29][30]

Challenges

One of the major challenges in reducing the burden of breast cancer in Sub Saharan Africa remains the lack of National Cancer Control Programs and the lack of human as well as financial resources.[26] The majority of countries lack integrated prevention and treatment programs, which complicates the control of the disease in those countries. Also, the regions disposes of a disproportionally low number of cancer registries, along with resources and facilities for treatment.[27] This all factors into the different countries' difficulties to ensure that women at high risk are identified and that the disease is diagnosed early enough to have better chances of being treated.[26][27] The lack of affordable and effective treatment methods also renders the efforts to promote early detection because those affected are then faced with inaccessible and unaffordable resources in the cases where they are available.[26] The challenges to tackling breast cancer in Africa are varied, not fully understood, and further complicated by possible unique risk factors that could be highlighted by further studies,[27] but developing strategies that foster early detection are viewed in literature as a priority for effective fight against the disease.[31]

Male breast cancer

Male breast cancer is a much less talked about issue due to its lower incidence with less than 1% of breast cancer in Sub Saharan Africa.[32] A review of the disease found that male to female ratio was higher in Sub Saharan Countries than in developed countries and that onset of the disease occurred on average 7 years latter in men than in women.[32] There is a noticeable decrease in the male to female breast cancer ratio in recent years but that might be associated to the recent increase in female breast cancer in the region. There is still little understanding of the causes of the higher risk for male breast cancer in Sub Saharan Africa and on male breast cancer in general, leading to poor clinical management of the disease.[32]

References

- "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Retrieved Nov 11, 2009.

- "World Cancer Report". International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2008. Archived from the original on 2011-01-14. Retrieved 2011-02-26.(cancer statistics often exclude non-melanoma skin cancers such as basal cell carcinoma which though very common are rarely fatal)

- "Breast cancer: prevention and control". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2015-09-06.

- Laurance, Jeremy (2006-09-29). "Breast cancer cases rise 80% since Seventies". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- "Breast Cancer: Statistics on Incidence, Survival, and Screening". [Imaginis Corporation]. 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-09.

- Breast Cancer: Breast Cancer in Young Women WebMD. Retrieved on September 9, 2009

- Youlden, Danny R. (Winter 2012). "The Descriptive Epidemiology of Female Breast Cancer: An International Comparison of Screening, Incidence, Survival and Mortality" (PDF). Cancer Epidemiology. 36 (3): 237–248. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2012.02.007. PMID 22459198.

- B. W. and Kleihues P. (Eds): World Cancer Report. IARCPress. Lyon 2003

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. (2008). "Cancer statistics, 2008". CA Cancer J Clin. 58 (2): 71–96. doi:10.3322/CA.2007.0010. PMID 18287387. Archived from the original on 2011-07-03.

- American Cancer Society (September 13, 2007). "What Are the Key Statistics for Breast Cancer?". Archived from the original on January 5, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- Olson, 2002. pages 199–200.

- W.B. Cutler; R.E. Burki; E. Genovesse; M.G. Zacher (September 2009). "Breast cancer in postmenopausal women: what is the real risk?". Fertility and Sterility. 92 (3): S16. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.07.061.

- "Browse the SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975–2006".

- American Cancer Society (2007). "Cancer Facts & Figures 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 10, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-26.

- "Male Breast Cancer Causes, Risk Factors for Men, Symptoms and Treatment on". Medicinenet.com. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- Espey DK, Wu XC, Swan J, et al. (2007). "Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2004, featuring cancer in American Indians and Alaska Natives". Cancer. 110 (10): 2119–52. doi:10.1002/cncr.23044. PMID 17939129.

- "Female Breast Cancer - Cancer Stat Facts".

- "Women's Fear of Heart Disease Has Almost Doubled in Three Years, But Breast Cancer Remains Most Feared Disease" (Press release). Society for Women's Health Research. 2005-07-07. Archived from the original on 2007-10-21. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- "Leading Causes of Death for American Women 2004" (PDF). National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- In Breast Cancer Data, Hope, Fear and Confusion, By DENISE GRADY, New York Times, January 26, 1999.

- chart for Figure 1.1: Breast Cancer (C50), Average Number of New Cases per Year and Age-Specific Incidence Rates, UK, 2006-2008 at Breast cancer - UK incidence statistics Archived 2012-05-14 at the Wayback Machine at Cancer Research UK. Section updated 18/07/11.

- "Breast cancer statistics". Cancer Research UK. 2015-05-14. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- Abdulrahman, Ganiy Opeyemi (2 May 2017). "Breast cancer in Wales: time trends and geographical distribution". Gland Surgery. 3 (4): 237–242. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2014.11.01. PMC 4244508. PMID 25493255.

- (Schwartzmann, 2001, p 118)

- Abdulrahman, Ganiy Opeyemi; Rahman, Ganiyu Adebisi (1 January 2012). "Epidemiology of breast cancer in europe and Africa". Journal of Cancer Epidemiology. 2012: 915610. doi:10.1155/2012/915610. PMC 3368191. PMID 22693503.

- Pace, Lydia E.; Shulman, Lawrence N. (2016-06-01). "Breast Cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and Opportunities to Reduce Mortality". The Oncologist. 21 (6): 739–744. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0429. ISSN 1083-7159. PMC 4912363. PMID 27091419.

- Brinton, Louise A.; Figueroa, Jonine D.; Awuah, Baffour; Yarney, Joel; Wiafe, Seth; Wood, Shannon; Ansong, Daniel; Nyarko, Kofi; Wiafe-Addai, Beatrice (April 2014). "Breast Cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa: Opportunities for Prevention". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 144 (3): 467–478. doi:10.1007/s10549-014-2868-z. ISSN 0167-6806. PMC 4023680. PMID 24604092.

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet] Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013.

- Espina, Carolina (2017-09-17). "Delayed presentation and diagnosis of breast cancer in African women: a systematic review". Annals of Epidemiology. 27 (10): 659–671.e7. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.09.007. PMC 5697496. PMID 29128086.

- Youlden, Danny R.; Cramb, Susanna M.; Dunn, Nathan A. M.; Muller, Jennifer M.; Pyke, Christopher M.; Baade, Peter D. (2012-06-01). "The descriptive epidemiology of female breast cancer: An international comparison of screening, incidence, survival and mortality" (PDF). Cancer Epidemiology. 36 (3): 237–248. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2012.02.007. PMID 22459198.

- Jedy-Agba, Elima; McCormack, Valerie; Adebamowo, Clement; dos-Santos-Silva, Isabel (2016-12-01). "Stage at diagnosis of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet Global Health. 4 (12): e923–e935. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30259-5. ISSN 2214-109X. PMC 5708541. PMID 27855871.

- Ndom, Paul (June 2017). "A meta-analysis of male breast cancer in Africa". The Breast. 21 (3): 237–241. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2012.01.004. PMID 22300703.