Empire Mine State Historic Park

Empire Mine State Historic Park is a state-protected mine and park in the Sierra Nevada mountains in Grass Valley, California, U.S. The Empire Mine is on the National Register of Historic Places, a federal Historic District, and a California Historical Landmark. Since 1975 California State Parks has administered and maintained the mine as a historic site. The Empire Mine is "one of the oldest, largest, deepest, longest and richest gold mines in California".[3] Between 1850 and its closure in 1956, the Empire Mine produced 5.8 million ounces of gold, extracted from 367 miles (591 km) of underground passages.[4]

| Empire Mine State Historic Park | |

|---|---|

View down the main drift at Empire Mine | |

| |

| Location | Nevada County, California, USA |

| Nearest city | Grass Valley, California |

| Coordinates | 39°12′13″N 121°2′34″W |

| Area | 853 acres (345 ha) |

| Established | 1975 |

| Governing body | California Department of Parks and Recreation |

Empire Mine | |

| Area | 777 acres |

| Built | 1896 |

| Architect | Polk, Willis |

| NRHP reference No. | 77000318[2] |

| CHISL No. | 298[1] |

| Added to NRHP | December 09, 1977 |

History

In October 1850, George Roberts discovered gold in a quartz outcrop on Ophir Hill,[5] but sold the claim in 1851 to Woodbury, Parks and Co. for $350 (or about $11,000 today, adjusted for inflation). The Woodbury Company consolidated several local claims into the Ophir Hill Mine, but they mismanaged their finances and in 1852 were forced to sell the business at auction.[5] It was purchased by John P. Rush and the Empire Quartz Hill Co.[6]:27 The Empire Mining Co. was incorporated in 1854, after John Rush was bought out.[6]:15,28[7]:87 As word spread that hard rock gold had been found in California, miners from the tin and copper mines of Cornwall, England, arrived to share their experience and expertise in hard rock mining. Particularly important was the Cornish contribution of the Cornish engine, operated on steam, which emptied the depths of the mine of its constant water seepage at a rate of 18,000 US gal (68,000 l; 15,000 imp gal) per day.[6]:19–21 This enabled increased productivity and expansion underground. Starting in 1895, Lester Allan Pelton's water wheel provided electric power for the mine and stamp mill.[6]:16 The Cornish provided the bulk of the labor force from the late 1870s until the mine's closure eighty years later.

William Bowers Bourn acquired control of the company in 1869.[6]:31 Bourn died in 1874, and his estate ran the mine, abandoning the Ophir vein for the Rich Hill in 1878.[6]:34 Bourn's son, William Bowers Bourn II, formed the Original Empire Co. in 1878, took over the assets of the Empire Mining Co., and continued work on the Ophir vein after it was bottomed out at 1,200 feet (370 m) and allowed to fill with water.[7]:87[8] With his financial backing, and after 1887, the mining knowledge and management of his younger cousin George W. Starr, the Empire Mine became famous for its mining technology.[6]:36[7]:87 Bourn purchased the North Star Mine in 1884, turning it into a major producer, and then sold it to James D. Hague in 1887, along with controlling interest in the Empire a year later.[6]:37

Bourn reacquired control of the Empire Mine in 1896, forming the Empire Mines and Investment Co. In 1897, he commissioned Willis Polk to design the "Cottage", using waste rock from the mine. The "Cottage" included a greenhouse, gardens, fountains and a reflecting pool. Between 1898 and 1905, a clubhouse with tennis courts, bowling alley and squash courts were built nearby.[6]:39

The Empire Mine installed a cyanide plant in 1910, which was an easier gold recovery process than chlorination. In 1915, Bourn acquired the Pennsylvania Mining Co., and the Work Your Own Diggings Co., neighboring mines, which gave the Empire Mines and Investment Co. access to the Pennsylvania vein. The North Star also had some rights to that vein, but both companies compromised and made an adjustment.[6]:45,48

In 1928, at the recommendation of Fred Searls of Nevada City, Newmont Mining Corp. purchased the Empire Mine from Bourn. Newmont also purchased the North Star Mine, resulting in Empire-Star Mines, Ltd.[7]:87 The business was managed by Fred Nobs and later by Jack Mann.

Gold mines were defined as "nonessential industry to the war effort" by the War Production Board of the US Government on 8 October 1942, which shut down operations until 30 June 1945. After the war, a shortage of skilled miners forced the suspension of operations below the 4,600-foot level by 1951.[6]:74–75

By the 1950s inflation costs for gold mining were leaving the operation unprofitable. In 1956 a crippling miners' strike over falling wages ended operations.[6]:77 Ellsworth Bennett, a 1910 graduate of the Mackay School of Mines in Reno was the last "Cap'n" (Superintendent) of the Empire, and the only person from management allowed across the picket line (the miners' lives depended on his engineering skills and they worked as a team). Bennett oversaw the closing of the Empire on May 28, 1957 when the last Cornish water pumps were shut and removed. In its final year of operation in 1956, the Empire Mine had reached an incline depth of 11,007 ft (3,355 m).

In 1974 California State Parks purchased the Empire Mine surface property for $1.25 million ($6.48 million today), to create a state historic park.[6]:81 The state park now contains 853 acres (345 ha; 3.45 km2; 1.333 sq mi),[9] including forested backcountry.[3] Newmont Mining retained the mineral rights to the Empire Mine, and 47 acres, if they decide to reopen the Empire Star Mines.[6]:81

Geology

A Granodiorite body five miles (8 km) long, north to south, and up to two miles (3.2 km) wide, underlies the district. This body intruded into surrounding metamorphic rocks. Gold ore deposits reside in the quartz veins, ranging from 3 to 7 ounces per ton. The Empire Vein outcrops to the east on a north-south strike, dipping at a 35-degree angle to the west. The vein was mined with inclined shafts following dip, with horizontal shafts (drifts) every 300–400 ft (90–120 m) along strike. The ore was mined by stoping.[6]:25[10]:53–59

Museum

On weekends from May through October, volunteers dressed in Edwardian clothing give living history tours of the Bourn Cottage, the 1890s country estate home of William Bourn, Jr., and the Mineyard, with demonstrations of mine operations.

The park's museum contains a scale model of the underground workings of the Empire/Star mine complex, exhibits of ore samples from local mines, a recreated Assay Office and a collection of minerals. There are 13 acres (5.3 ha) of gardens to tour.

The Sierra Gold Park Foundation (SGPF) provides the interpretive and educational goals of this state historic park through donations, visitor center sales, membership dues and special events. It has a very active volunteer group.

See also

References

- "Empire Mine". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2012-10-10.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- "Empire Mine SHP". California State Parks. Archived from the original on 2011-12-16. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

- Forgione, Mary (February 21, 2014). "California: Park scraps gold mine tour after spending $3.5 million". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- Lescoher, Roger (1995). Gold Giants of Grass Valley. Empire Mine Park Association.

- McQuiston, F.W., 1986, Gold: The Saga of the Empire Mine, 1850-1956, Grass Valley:Empire Mine Park Association, ISBN 9780931892073

- Johnston, W.D., 1940, The Gold Quartz Veins of Grass Valley, California, USGS Professional Paper 194, Washington:US Government Printing Office

- Fullwood, Janet (1998-04-26). "In Grass Valley, the Empire Mine was California's biggest, most productive operation". Sacramento Bee. Sacramento, Calif. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

- "California State Park System Statistical Report: Fiscal Year 2009/10" (PDF). California State Parks: 32. Retrieved 2011-12-16. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Clark, W.B., 1963, Gold Districts of California, Bulletin 193, Sacramento: California Division of Mines and Geology

Gallery

Mule hauling an ore car in 1910

Mule hauling an ore car in 1910 Shift change in 1900

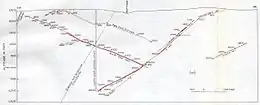

Shift change in 1900 Geologic cross section showing the relationship of the Empire and North Star Veins

Geologic cross section showing the relationship of the Empire and North Star Veins

Further reading

- Empire Mill and Mining Company (Gold Hill, Nev.), Giffin, O. G., Graves, W., & Nesmith, J. G. (1861). Empire Mill and Mining Company Collection.

- Wagner, H. H. (1939). The Empire Mine, Nevada County : registered landmark #298. California historical survey series : historic landmarks, monuments and state parks. Berkeley, Calif: State of California, Dept. of Natural Resources, Division of Parks.

- Carey, L. F. (1971). The Empire Mine properties: 1122 acres in the Sierra Nevada foothills, Grass Valley, Nevada County, California. Grass Valley, Calif: L.F. Carey, Realtor, Investment Properties.

- Steinfeld, C. C. (1996). The Bourn dynasty: the Empire Mine's golden era, 1869–1929. Grass Valley, CA: Empire Mine Park Association.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Empire Mine State Historic Park. |