Elizabeth Hickok Robbins Stone

Elizabeth Hickok Robbins Stone (September 21, 1801 - December 4, 1895) was an American pioneer woman who was inducted into the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame in 1988. Born in Connecticut and raised in New York, Elizabeth Hickok was married and widowed twice and had 8 children from her first marriage to Dr. Ezekiel Robbins. Most of her adulthood was spent as a pioneer, building homes and businesses with her husbands in Missouri, Illinois, Minnesota and Colorado. Both of her husbands participated in developing statehoods: Ezekiel Robbins in Illinois and Lewis Stone in Minnesota.

At about 62 years of age Elizabeth Robbins Stone and her second husband, Lewis Stone, took their wagon from Minnesota to Denver, Colorado where they operated a hotel for a few years. They then went north to Camp Collins, Colorado and built a house to provide the army officers' mess.

After her second husband, Lewis Stone, died, Elizabeth Stone ran the first hotel in the Fort Collins area, serving Overland Trail travelers. Stone financed and initiated businesses to support the growth in and around the Fort Collins, Colorado area. With her partner, Henry Clay Peterson, she had the first mill in Larimer County, Colorado and the second mill in Colorado. The settlement's first school was started in her home by her niece, Elizabeth Keays. After the "Great Fire of Denver" in 1863, she financed the building of the first brick kiln in the region. She owned and operated several hotels.

Early life

Elizabeth Hickok was born in Hartford, Connecticut on September 21, 1801 to David and Adah Hickok. The Hickok family moved to Watertown, New York in 1805.[1] In the early 19th century education for girls was not generally considered important, the rationale was that as women they would be primarily responsible for household duties and raising children which would not require them to be literate.[2] Unlike many girls at that time, Hickok learned to read and write.[3]

Marriages and children

Dr. Ezekiel W. Robbins

Elizabeth Hickok married her first husband, Dr. Ezekiel W. Robbins, on February 22, 1824 in Watertown, New York.[1] Ezekiel was born to Robert Robbins and Lucy Wright on August 20, 1802 in Verona, New York.[4] During the early 1820s, the Universalist Society was established in Watertown. Some parishioners of local churches wished to be dismissed from their church to enable them to join the Universalist church. Of Ezekiel, Pitt Morse, the first Universalist minister in the Watertown area, noted:

Some time during the winter past, Ezekiel W. Robbins, a young man of unblemished moral character, was excluded from the Congregational Church in Adams, merely for believing in the fulfillment in the divine mission of Christ.[5]

In June, 1824, Robbins received a letter of fellowship to the Universalist church.[6]

Elizabeth and Ezekiel had 2 children by 1828, one of whom was Washington I. Robbins, when they moved by wagon to the booming town of St. Louis, Missouri.[3][4] St. Louis, a departure point for the western frontier, was known as the "Gateway to the West".[7] Dr. Robbins established a medical practice and Elizabeth cared for the family, which grew to include 8 children.[3] Robert and Lucy Robbins, Ezekiel's parents, also moved to St. Louis; Robert died there in 1831 and Lucy in 1858.[4]

Between 1838 and 1840, the Robbins family moved to Chester, Illinois where Dr. Robbins established several public schools.[1][3] Dr. Robbins represented Randolph county, Illinois from 1844 to 1846 at the Fourteenth General Assemblies[8] and from 1847 to 1848 at the Illinois constitution convention in Springfield, Illinois.[9][10]

Their children included Washington, Lucy, Theodoria, Ellen, Walter, Dewitt, James and another child whose name is unknown.[4][11][12] In 1850, living at home with Elizabeth and Ezekiel, were daughter Ellen and three sons: Walter, Dewitt and James, ranging from 18 to 11 years of age.[11]

Ezekiel Robbins died on July 25, 1852 of cholera[3] during the epidemic raging in the midwestern United States from 1849 to 1855. At this time, there were no standard practices for prevention of infectious disease, such as specialized medical training, prevention, sanitation engineering or isolation of ill patients. In its early history, Illinois had a high incidence of infectious diseases.[13]

Elizabeth Robbins, who still had three sons to raise, moved back to New York for a period of time.[1][3]

Lewis Stone

In 1857 Elizabeth Hickok Robbins moved to the Minnesota prairie and married widower Lewis Stone[1][3] who immigrated from New Brunswick, Canada to Maine and then St. Anthony, Minnesota by 1850 with his previous wife, also named Elizabeth (born 1797 in Maine), and their children Jacob, Leonard, Joshua, Ezekiel, Rhodence, Lewis and Wallace.[14]

Living with Elizabeth Robbins Stone and Lewis Stone in 1857 were Lewis' sons Ezekiel (22) and Wallace (15).[15] In 1853 Lewis Stone and his brother George helped found the settlement of Langola, also called "Platte River", where they owned and operated the Stone Hotel and dining room.[16][17] In 1856 Stone was a representative for Benton County in the Minnesota territorial legislature. He was sometimes called "Judge" Lewis Stone, having served as a judge of elections in Stearns County, Minnesota in the 1858 statehood election.[18][19][nb 1]

According to letters written by James Fergus to his wife back in Minnesota, Lewis Stone traveled to Colorado in the spring of 1860 and panned for gold in "Gregory Diggings" [now Central City, Colorado].[nb 2] Elizabeth Stone remained at their home on the Platte river in Langola, Minnesota, sharing responsibility for running the Stone Hotel with Lewis' brother George and sister-in-law Mahalia Stone. Living with Elizabeth were step-son Ezekiel Stone and his children.[14][21] Traveling by covered wagon, the Stones made their way across Nebraska and down the South Platte River to Denver in 1862 where they purchased 12 lots. On the property was a restaurant and/or a "hotel" on land that is now part of Denver's Union Station.[3][22][23]

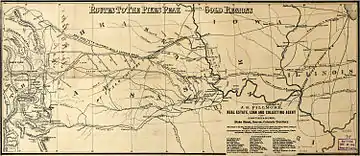

Map of the South Platte River watershed in Colorado from North Platte, Nebraska

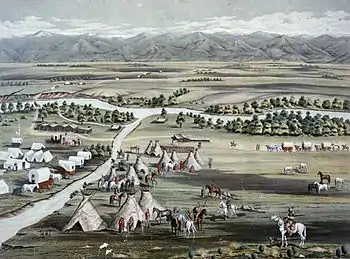

Map of the South Platte River watershed in Colorado from North Platte, Nebraska Denver, Colorado [Cherry Creek off the South Platte River] in 1859

Denver, Colorado [Cherry Creek off the South Platte River] in 1859

Leaving the Denver property in the hands of Lewis Stone's son,[23] the Stones moved in September, 1864 to an army post, Camp Collins, north of Denver to manage the officer's mess. The post was built to guard the overland mail route and to protect settlers from unfriendly Native American tribes. The post consisted of tents and a few cabins along the Cache la Poudre River. In 1890 the Rocky Mountain News described the camp as "nothing more than a parade ground and flagpole with three log huts on one side for officer's quarters, and on the east and west... log barracks for the men." The Stones were given permission to build a two-story house to serve as the mess quarters and their home; Within one month they were ready to use the building as a mess hall[3] and take in officers as boarders.[22] For the first year, Stone was the only woman in town. Described as a "merry" woman and gracious hostess, the men at Camp Collins nicknamed her "Auntie" Stone. Her husband, Lewis Stone, died in January, 1866[3] and was buried in the post's cemetery.[23]

Routes to Colorado, including the Overland Route

Routes to Colorado, including the Overland Route Camp Collins, Colorado in 1865

Camp Collins, Colorado in 1865 Stone's house, Camp Collins mess hall and later hotel

Stone's house, Camp Collins mess hall and later hotel Early Fort Collins cabins

Early Fort Collins cabins

Role in Fort Collins development

.jpg.webp)

A widow again about 64 years of age, Elizabeth played a part in Fort Collin's history in several ways. She was the first Euro American woman settler who created a sense of community for the soldiers at Camp Collins and the only woman founder of the town of Fort Collins.[23] She also created and ran several businesses.[24]

School

Shortly after Lewis Stone died Stone heard from her niece that she was recently widowed. At Stone's encouragement, Elizabeth Keays came to Colorado with her son, Wilbur[22] and moved in with her. Keays described the two-story cabin as a "very comfortable home for this country with three large rooms below and chambers for sleeping rooms." She and her young son shared a spare room with its "ingrain carpet, nice bed, window with a nice sunset view."[24]

Beginning in June 1866, Keays opened the settlement's first school in her aunt's home with 14 students[22] soon after she arrived from Illinois. In September, after a school board was formed, she was employed as the sole teacher in the first public school in Fort Collins. Abandoned officers' quarters were used as a schoolhouse. Elizabeth Keays married Harris Stratton on December 30, 1866, the first wedding ceremony in Fort Collins, and remained in the Old Fort Site in the late 1860s.[25]

Hotels

Pioneer Hotel

- The army decommissioned Camp Collins in March 1867, so the house built as an officer's mess was turned into the first hotel in Fort Collins, Colorado by Stone, which housed and fed Overland Trail travelers.[24] She also sold pies, bread, milk and butter to the soldiers.[22]

- After their marriage, the Strattons lived at Stone's house and took in boarders for the railroad. Stone lived at the newly built mill and took in boarders there who installed the mill machinery. The same year she obtained a land patent for 160 acres, becoming the first woman landowner and taxpayer in Larimer County.[22]

- Located in the 300 block of Jefferson Street, the two-story hotel was called "Pioneer Cabin", and used by the Pioneer organizations for meetings and dances. Stone sold the house to Marcus Coon in 1873 who moved it to a location where it became kitchen and laundry facilities for the Agricultural Hotel.[26] Later, it was sold to Mr. and Mrs. James F. Vandewark, who covered it in siding, painted it white and made it their home.

Cottage House

- From bricks made at her brick making business, Stone built Cottage House and ran a hotel out of it[24] until 1881 when her daughter, Theodosia Van Brunt, arrived from Illinois to take over its operation.[27]

- It was a large house with two porches on Jefferson Street. It was run by John Tingle, then Frank Campbell and his sister, Elizabeth Rich, who made improvements to the building. It was a popular place to stay for students who attended Agricultural College of Colorado, later Colorado State University, while they found a residence for the school year.

Blake House Hotel

- In 1873, she bought the Blake House Hotel.[24] The same year, she advertised her "National Hotel" in the "Handbook for Colorado" publication. In 1878, she renamed it "Metropolitan Hotel" and the following year it was taken over by B.S. Tedmon.[28]

- The Blake House, located in the 200 block of Jefferson Street, was built by George G. Blake in 1870. It was a large frame building with two traditional front porches. In 1871, Harry Conly was the proprietor. The Blake House was one of the hotels which was torn down to make way for the Union Pacific Railroad.

Grist Mill

In 1867 Stone developed a partnership with Henry Clay Peterson, the town's gunsmith; She provided the financing and initial ideas and Peterson oversaw the execution of the projects. The first was creation of a three-story grist mill, the town's tallest building, to meet the needs of the new wheat farms in the region.[29] It was first flour mill built in Larimer County, second in the state of Colorado, and powered by the water of the Cache la Poudre River.[23] It was built at the Old Fort site on the south side of the river with a 1½ mile long millrace to supply water power.[30] "Linden Mill" began production of flour in 1869 and its third floor was used for Masonic Lodge meetings beginning in 1870. At the end of 1873 both Peterson and Stone had sold their interests in the mill.[28]

The first mill in Colorado was operated by Andrew Douty near Boulder, southwest of Fort Collins; In 1867 he moved the mill to Old St. Louis, a previous settlement near Loveland.[31]

Brick making

Seven years after the "Great Fire of Denver of 1863" that demolished many of Denver's downtown buildings,[32] Stone realized that Fort Collins buildings were all wooden frame structures and built a brick kiln and founded a brick making business so that more formidable, permanent structures could be built. She and her partners operated the region's first brick kiln[29] at the site of the Old Fort in 1870.[30]

Community and civic activities

Assisting in the delivery of Fort Collins' first baby, Agnes Mason, Stone was also the town's first mid-wife.[22][33]

She contributed to every church in town and towards the creation of the Colorado Agriculture College, now Colorado State University. She was a founding member of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union. In 1879, she held a "good" dinner for men who met their promise not to enter a saloon for two months, and in 1881, helped form the Temperance Union and was elected treasurer.[27]

Later years

On her 81st birthday, four generations of her family attend a party held in her honor where she danced until 5 a.m. and then went home to make breakfast for everyone; She danced until she was 86 years of age.[27]

In 1885, when Stone was about 84 years of age, the Fort Collins Courier reporter described her: "She walks erect, reads a great deal, and talks sensibly. She curls her hair, wears her watch and chain, and dresses up for the afternoons as if she were yet a belle. In fact, she is a belle."[29] An advocate for women's right to vote, she cast her first vote at age 93, one year after Colorado women were granted the right to vote.[34]

In 1894 the Fort Collins Express identified six living children: Mr. W.I. Robins, Mr. Dewitt C. Robbins, Mr. James M. Robbins, Mrs. Lucy Fallis, Mrs. Theodoria Van Brunt and Mrs. Ellen Ray.[12]

Stone died on December 4, 1895. Her funeral was officiated by ministers of Presbyterian, Methodist, Episcopalian and Baptist churches.[23] In her honor, all of the town's businesses were closed for two hours. As she was interred the firehouse bell rang 94 times, once for each year of her life.[29] Stone is buried at the Grandview Cemetery in Fort Collins. Her grave has a granite marker. When the cemetery was created in 1873, six graves from the Camp Collins post cemetery were moved to the Grandview Cemetery,[35] one of which may have been her husband, Lewis Stone, who was buried at the camp.

The only remaining building associated with Camp Collins is "Auntie" Stone's cabin,[36] now located at the Heritage Center at the Fort Collins Museum in downtown Fort Collins.[29] She was inducted into the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame in 1988.[33] In 1991, "Auntie Stone Street" in southwest Fort Collins was named in her honor, "the founding mother" of Fort Collins.[34]

See also

- Clara Brown, another Colorado pioneer woman inducted into the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame

Notes

- Benton County was one of the first Minnesota counties starting in 1849. In 1855 Stearns County was formed [from a portion of Benton county].[20] Although Stone was said to be a territorial representative for Benton County in 1856, the area of the Langola settlement is now in Stearns County. Perhaps the now adjacent Benton and Stearns county lines shifted between 1855 (Stearns county formed from Benton County) and 1858 (when Stone was a judge of elections in Stearn County).

- Gregory Diggings is more commonly called "Gregory Lode" or "Gregory Gulch".

References

- Funke, 1.

- Fortin, Early Nineteenth Century Attitudes Toward Women and Their Roles.

- Varnell, 5-7.

- Thurtle, p. 225.

- Perciaccante, pp. 90-92.

- Loveland, pp. 141-142.

- St. Louis - Gateway to the West.

- Combined history of Randolph, Monroe and Perry counties, Illinois, pp. 124, 149.

- Lusk, 496-497.

- Combined history of Randolph, Monroe and Perry counties, Illinois, p. 121.

- 1850 U.S. Federal Census, Illinois, Randolph, Township 7 S R 5 W, p. 13.

- Mrs. Elizabeth Stone, Fort Collins Express.

- History of Medical Practice, p. 3, 151, 239-240.

- Peavy, Smith, p. 53.

- 1857 Minnesota Territorial and State Censuses, Township 38.

- Neil, Langola Township history

- Peavey, Smith, pp. 41, 53, 251.

- Folsom, p. 433.

- Peavey, Smith, p. 251.

- Folsom, pp. 432, 460, 710.

- U. S. Federal Census 1860 for Langola, Benton County, Minnesota.

- Funke, 2.

- Wommack, 212-213.

- Varnell, 6.

- City of Fort Collins, Old Fort Site, 20.

- City of Fort Collins, Old Fort Site, 18.

- Funke, 3.

- Funke, 2-3.

- Varnell, 7.

- City of Fort Collins, Old Fort Site, 7.

- Feneis, The History of Loveland.

- Denver History: Denver's Beginnings.

- Elizabeth Hickok Robbins Stone, Colorado Women's Hall of Fame.

- Funke, 4.

- Wommack, 208, 213.

- City of Fort Collins, Old Fort Site, 19.

Bibliography

- Combined history of Randolph, Monroe and Perry counties, Illinois. Philadelphia: J.L. McDonough. 1883. Retrieved 2011-07-08.

- "Denver History: Denver's Beginnings". Visit Denver, The Convention and Visitors Bureau. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- "Elizabeth Hickock Robbins Stone". Colorado Women's Hall of Fame. 2003–2011. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- Feneis, Jeff; Feneis, Cindy (2009). "The History of Loveland, Colorado". Loveland Historical Society. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- Folsom, William Henry Carman (1999) [1888]. Fifty Years in the Northwest. Taylor Falls Historical Society. p. 433.

Link provided to page 433 in the 1888 version published by Pioneer Press Company.

- Fortin, Elaine. "Early Nineteenth Century Attitudes Toward Women and Their Roles". Teach US History. Retrieved 2011-07-08.

- Funke, Teresa. "Auntie Stone biography" (PDF). Poudre Libraries. Retrieved 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Davis, David J., ed. (1955). History of Medical Practice in Illinois. Chicago: The Lakeside Press, R. R. Donnelley & Sons. Retrieved 2011-07-08.

- Loveland, Samuel (1825). Universalist Historical Society, The Christian Repository. V. Woodstock: David Watson.

- Lusk, David (1884). Politics and politicians: a succinct history of the politics of Illinois. Springfield, Illinois: H. W. Rokker. p. 496. OCLC 3339697.

- "Mrs. Elizabeth Stone". Fort Collins Express: 35. January 1, 1894. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- "Old Fort Site: Historical Contexts for the Old Fort Site, Fort Collins, Colorado, 1864-2002". City of Fort Collins, Colorado. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- Peavy, Linda; Smith, Ursula (1990). The Gold Rush widows of Little Falls. Minnesota Historical Society Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-87351-249-9.

- Perciaccante, Marianne (2003). Calling down fire: Charles Grandison Finney and revivalism in Jefferson County, New York. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 90. ISBN 0-7914-5639-0.

- "St. Louis - Gateway to the West". www.Legends of America.com. 2003–2011. Retrieved 2011-07-08.

- Thurtle, Robert Glenn (1980). Lineage Book of Hereditary Order of Descendants of Colonial Governors. ISBN 9780806350875.

- "United States Federal Census - Randolph County, Illinois". Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29; National Archives, Washington, D.C. 1850. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Varnell, Jeanne (1999). Women of Consequence: The Colorado Women's Hall of Fame. Boulder: Johnson Press. ISBN 1-55566-214-5.

- Wommack, Linda (1998). From the grave: a roadside guide to Colorado's pioneer cemeteries. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Press. ISBN 0-87004-390-0.

Further reading

- Mumey, Nolie (1964). The saga of "Auntie" Stone and her cabin: Elizabeth Hickok Robbins Stone (1801-1895). Boulder: Johnson Publishing. Includes the overland diary of her niece, Elizabeth Parke Keays.

External links

- "Heritage Courtyard: The Auntie Stone cabin, the oldest remaining building from the Fort era". Fort Collins Museum & Discovery Science Center. Archived from the original on June 19, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- Colorado Women's Hall of Fame