Electrode

An electrode is an electrical conductor used to make contact with a nonmetallic part of a circuit (e.g. a semiconductor, an electrolyte, a vacuum or air). The word was coined by William Whewell at the request of the scientist Michael Faraday from two Greek words: elektron, meaning amber (from which the word electricity is derived), and hodos, a way.[1][2]

The electrophore, invented by Johan Wilcke, was an early version of an electrode used to study static electricity.[3]

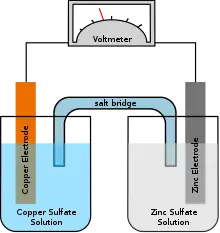

Anode and cathode in electrochemical cells

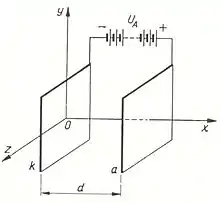

An electrode in an electrochemical cell is referred to as either an anode or a cathode (words that were coined by William Whewell at Faraday's request).[1] The anode is now defined as the electrode at which electrons leave the cell and oxidation occurs (indicated by a minus symbol, "−"), and the cathode as the electrode at which electrons enter the cell and reduction occurs (indicated by a plus symbol, "+"). Each electrode may become either the anode or the cathode depending on the direction of current through the cell. A bipolar electrode is an electrode that functions as the anode of one cell and the cathode of another cell.

Primary cell

A primary cell is a special type of electrochemical cell in which the reaction cannot be reversed,[4] and the identities of the anode and cathode are therefore fixed. The anode is always the negative electrode. The cell can be discharged but not recharged.

Secondary cell

A secondary cell, for example a rechargeable battery, is a cell in which the chemical reactions are reversible. When the cell is being charged, the anode becomes the positive (+) and the cathode the negative (−) electrode. This is also the case in an electrolytic cell. When the cell is being discharged, it behaves like a primary cell, with the anode as the negative and the cathode as the positive electrode. Charging and discharging processes, such as those in lithium-ion batteries, tend to incur large losses through contact resistance at electrodes. Minimising these electrode localised losses constitutes an important approach in improving energy usage in electrochemical storage.

Other anodes and cathodes

In a vacuum tube or a semiconductor having polarity (diodes, electrolytic capacitors) the anode is the positive (+) electrode and the cathode the negative (−). The electrons enter the device through the cathode and exit the device through the anode. Many devices have other electrodes to control operation, e.g., base, gate, control grid.

In a three-electrode cell, a counter electrode, also called an auxiliary electrode, is used only to make a connection to the electrolyte so that a current can be applied to the working electrode. The counter electrode is usually made of an inert material, such as a noble metal or graphite, to keep it from dissolving.

Welding electrodes

In arc welding, an electrode is used to conduct current through a workpiece to fuse two pieces together. Depending upon the process, the electrode is either consumable, in the case of gas metal arc welding or shielded metal arc welding, or non-consumable, such as in gas tungsten arc welding. For a direct current system, the weld rod or stick may be a cathode for a filling type weld or an anode for other welding processes. For an alternating current arc welder, the welding electrode would not be considered an anode or cathode.

Alternating current electrodes

For electrical systems which use alternating current, the electrodes are the connections from the circuitry to the object to be acted upon by the electric current but are not designated anode or cathode because the direction of flow of the electrons changes periodically, usually many times per second.

Uses

Electrodes are used to provide current through nonmetal objects to alter them in numerous ways and to measure conductivity for numerous purposes. Examples include:

- Electrodes for fuel cells

- Electrodes for medical purposes, such as EEG (for recording brain activity), ECG (recording heart beats), ECT (electrical brain stimulation), defibrillator (recording and delivering cardiac stimulation)

- Electrodes for electrophysiology techniques in biomedical research

- Electrodes for execution by the electric chair

- Electrodes for electroplating

- Electrodes for arc welding

- Electrodes for cathodic protection

- Electrodes for grounding

- Electrodes for chemical analysis using electrochemical methods

- Nanoelectrodes for high-precision measurements in nanoelectrochemistry

- Inert electrodes for electrolysis (made of platinum)

- Membrane electrode assembly

- Electrodes for Taser electroshock weapon

Chemically modified electrodes

Chemically modified electrodes are electrodes that have their surfaces chemically modified to change the electrode's physical, chemical, electrochemical, optical, electrical, and transportive properties. These electrodes are used for advanced purposes in research and investigation.[5]

See also

- Working electrode

- Reference electrode

- Gas diffusion electrode

- Cellulose electrode

- Battery

- Redox (Reduction-Oxidation Reaction)

- Cathodic protection

- Galvanic cell

- Anion vs. Cation

- Electron versus hole

- Electrolyte

- Electron microscope

- Noryl

- Tafel equation

- Hot cathode

- Cold cathode

- Electrolysis

- Reversible charge injection limit

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Electrodes. |

- Weinberg, Steven (2003). The Discovery of Subatomic Particles Revised Edition. Cambridge University Press. pp. 81–. Bibcode:2003dspr.book.....W. ISBN 978-0-521-82351-7. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- Faraday, Michael (1834). "On Electrical Decomposition". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2010-01-17. In this article Faraday coins the words electrode, anode, cathode, anion, cation, electrolyte, and electrolyze.

- Whitaker, Harry (2007). Brain, mind and medicine : essays in eighteenth-century neuroscience. New York, NY: Springer. p. 140. ISBN 978-0387709673.

- Sivasankar (2008). Engineering Chemistry. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 9780070669321. Archived from the original on 2017-12-21.

- Durst, R., Baumner, A., Murray, R., Buck, R., & Andrieux, C., "Chemically modified electrodes: Recommended terminology and definitions (PDF) Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine", IUPAC, 1997, pp 1317–1323.