Droxford railway station

Droxford railway station was an intermediate station on the Meon Valley Railway, built to a design by T. P. Figgis and opened in 1903. It served the villages of Droxford, Soberton and Hambledon in Hampshire, England.[upper-alpha 1] The railway served a relatively lightly populated area, but was built to main line specifications in anticipation of it becoming a major route to Gosport. Consequently, although the station was built in an area with only five houses, it was designed with the capacity to handle 10-carriage trains. It initially proved successful both for the transport of goods and passengers, but services were reduced during the First World War and the subsequent recession, and the route suffered owing to competition from road transport.

Droxford | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Location | Droxford, City of Winchester England |

| Coordinates | 50.9632°N 1.1291°W |

| Grid reference | SU613185 |

| Platforms | 2 |

| Other information | |

| Status | Disused |

| History | |

| Original company | London and South Western Railway |

| Pre-grouping | London and South Western Railway |

| Post-grouping | Southern Railway Southern Region of British Railways |

| Key dates | |

| 1 June 1903 | Opened |

| 7 February 1955 | Closed to passengers |

| 27 April 1962 | Closed to goods |

In 1944, amid World War II, Droxford station was used by the Prime Minister Winston Churchill as his base during preparations for the Normandy landings. Based in an armoured train parked in the sidings at Droxford, Churchill met with numerous ministers, military commanders and leaders of allied nations. On 4 June 1944, shortly before the landings were due to take place, Free French leader Charles de Gaulle visited Churchill at Droxford, and was informed of the invasion plans. When discussing the future governance of liberated France at this meeting, Churchill expressed his view that if forced to side with France or the United States he would always choose the United States, a remark which instilled in de Gaulle a suspicion of British intentions and caused long-term damage to the postwar relationship between France and Britain.

After the war, with Britain's railway network in decline, services on the Meon Valley Railway were cut drastically. A section of the line north of Droxford was closed, reducing Droxford to being the terminus of a short 9 3⁄4-mile (15.7 km) branch line. In early 1955 the station closed to passengers, and in 1962 it closed to goods traffic. Following its closure, Droxford station and a section of its railway track were used for demonstrating an experimental railbus until the mid-1970s. It then briefly served as a driving school for HGV drivers, before becoming a private residence and being restored to its original appearance.

Background

The River Meon rises in East Meon, and flows 21 miles (34 km) through rural Hampshire before entering the Solent at Hill Head.[2] With fertile farmland and access to the coast,[3] the valley of the Meon has been inhabited since at least the Mesolithic era.[4] The village of Droxford (from the Old English Drokeireford, "dry ford") is situated on sloping ground on the west bank of the Meon, overlooking a broad flood plain. The village has existed since at least the early 9th century; the vill of Drokeireford was granted by Ecgberht, King of Wessex to Herefrith, bishop of Winchester in 826 "for the sustenance of the monks of Winchester".[4] At that time, the village already contained three mills.[4] Droxford became the most important of the villages in the immediate area;[upper-alpha 2] by the late 19th century it housed the local post office and telegraph office, police station, workhouse and courthouse, and had its own brewery, manor house and flour mill.[4] In the 1901 census, taken shortly before the opening of the railway, Droxford and neighbouring Soberton on the east bank of the Meon had a combined population of 1687.[5]

Since 1851 there had been proposals to build a railway line through the Meon Valley,[6] but all proposals were abandoned owing to high construction costs or objections from local landowners. Consequently, by the end of the 19th century the area still had no easy access to a railway line, unlike most other communities in the country.[7]

To address this lack of service, in 1896 a group of wealthy locals proposed a railway running north–south from Basingstoke to Portsmouth. Although it would serve a lightly populated area and consequently be of little economic benefit, the proposal's supporters argued that it would be of strategic importance, connecting military facilities in Aldershot and Portsmouth with military training grounds in north Hampshire.[8] The line was to have been operated by the Great Western Railway (GWR) and the South Eastern Railway.[5]

The London and South Western Railway (LSWR) and London, Brighton and South Coast Railway, who between them controlled rail access to the major ports of Portsmouth and Southampton, were aghast at the prospect of the GWR controlling a route to the south coast, and lobbied against the proposal.[8] The LSWR promised the House of Lords Committee considering the proposal that if the scheme were rejected, the LSWR would build a line from Basingstoke to Alton and from Alton south along the Meon Valley to Fareham between Southampton and Portsmouth.[8] Although originally intending to build a light railway, when the LSWR made a formal proposal to Parliament in 1897 the proposal was for a railway built to main line specifications.[9][upper-alpha 3] The Long Depression had by this time been underway for over 20 years, severely lowering agricultural incomes and allowing the LSWR to buy land along the Meon Valley cheaply.[11]

Station site

_(1902)_showing_Droxford_and_surrounding_villages.png.webp)

Droxford lies on the west of the River Meon, and at the time was a large village surrounded by farmland; the station was built on the opposite side of the river, in neighbouring Soberton.[4] Soberton was closely associated with Droxford but had its own identity, and consisted of agricultural land interspersed with small settlements.[5][upper-alpha 4] Brockbridge, the part of Soberton chosen for the station, contained only five houses; it was chosen for its location at the meeting point of five roads close to a bridge over the Meon. It was accessible to Droxford, Soberton, and the important nearby village of Hambledon.[1] Although sited in Soberton, the station was to be named for the more important Droxford.[1][upper-alpha 1]

The chosen site was glebe land, historically owned by the Diocese of Winchester for the benefit of the parish of Meonstoke, of which Soberton was a part.[1] After centuries as a chapel of ease of the neighbouring parish of Meonstoke, in May 1897 Soberton became an independent parish in its own right.[13][upper-alpha 5] As such, the LSWR needed to persuade William Hammond Morley, the newly appointed rector of Soberton, of the benefits of the railway.[1][upper-alpha 6] On 22 November 1898 Morley provisionally agreed to sell the land for the station site for £425 (about £48,000 in 2021 terms[16]).[13] On 9 February 1899, following undertakings from the LSWR regarding fencing around the site and arrangements for access to remaining glebe land, the land was transferred to the LSWR.[15] Over the following weeks compensation was paid to those people whose homes or land would be affected by the building of the station or the rerouting of roads,[upper-alpha 7] and the LSWR was ready to proceed with construction.[15]

Construction

Construction of the line began in 1900, beginning at Alton and working south. The station site at Droxford was near high ground, and teams dug a deep cutting through the chalk to allow level access to the station. In mid-1900, the work team digging this cutting found human remains on the site.[17] Construction work ceased while police investigated; it was eventually determined that the remains were Anglo-Saxon.[18] Further bodies, along with metal jewellery and weapons, were discovered, and many of the human bodies had been covered with large pieces of flint.[17][18] It became obvious that the site was an Anglo-Saxon burial ground.[18] (Later excavations in 1974 identified the site as a pagan cemetery from the 5th and early 6th centuries.[19] A total of 41 graves were identified.[20]) Although the digging of the cutting was further delayed owing to labour shortages,[17] work was largely completed by January 1902.[21] By this time a hotel had opened near the site of the future station, named the Railway Hotel.[22]

The exact date of construction is unrecorded, but it is likely that Droxford station was built in 1902.[23] As with other stations on the line, the station building was designed by T. P. Figgis, an Irish architect who had designed many of the stations of the City and South London Railway (later to become part of London Underground's Northern line).[22] All the new stations for the line were of a very similar Tudor Revival design, built largely of red brick with Portland stone stonework, stained glass windows and lavatories in the shape of pagodas.[22]

.jpg.webp)

In anticipation of the route potentially becoming a major main line the station had two very long 600-foot (180 m) platforms, capable of handling 10-carriage trains, connected by a wooden footbridge.[23][24][25] In addition, the station had a corrugated iron goods shed with its own siding,[upper-alpha 8] and a signal box on the west (northbound) platform.[23] The two lines converged to a single track immediately north of the station, but continued southwards as a double track.[23] With plans for eventually doubling the track of the entire route, all cuttings, tunnels and bridges on the single-track section were built wide enough to accommodate a second track in future.[9] The station building also incorporated a house for the stationmaster and his family, situated immediately to the left of the main entrance to the platforms.[26][upper-alpha 9] In addition to the stationmaster's accommodation in the main building, four cottages for railway staff were built to the immediate west of the station,[27] and a coal yard was built near the station.[28]

Although the station building was complete, work was proceeding more slowly than anticipated on the construction of the railway line, and the proposed opening date of 25 March 1903 was missed.[29] While the route between Alton and Droxford was built on stable chalk, south of Droxford it entered the Reading Formation of stony clay, a surface on which it was difficult to build;[30] in addition, there were very few water sources for the steam-powered construction machinery and for mixing concrete, necessitating the drilling of multiple deep wells.[31] As well as this, construction work was regularly interrupted by bad weather.[32] The Meon Valley Railway was eventually completed and inspected for fitness by the Board of Trade on 6 April 1903, and the line opened to passengers on 1 June 1903.[23] At the time of opening, the station was staffed by a stationmaster and three signalmen, as well as assorted porters and clerical staff.[33]

Opening

The opening was relatively low-key, and no formal ceremony took place.[29] The opening day was Whit Monday, a bank holiday; local residents were each allowed to take one journey free of charge to the next station in either direction.[33] (The free fares were only valid for a single journey; those taking advantage of the offer were obliged either to pay for a return ticket, or to walk back.[29]) Although express services between London and Gosport were hauled by powerful LSWR A12 class locomotives, the only services to stop at Droxford were local trains between Fareham and Alton, hauled by less powerful LSWR 415 class tank engines built in the early 1880s.[33] Initially, Droxford was served by six services a day in each direction, with two trains in each direction on Sundays.[33]

The railway proved successful, and the availability of convenient travel to London prompted the construction of large luxury homes on the undeveloped land to the south of the station. By 1915 there were 19 new homes on the site; 12 of the 19 homes had a woman as the householder, and the development became nicknamed the "Widow's Villas".[34] Although important as a passenger facility, the main significance of Droxford station was its impact on the local agricultural economy. For the first time milk, livestock, vegetables and in particular strawberries from the numerous local strawberry farms could be shipped cheaply and quickly to market towns.[27][35] (Strawberry farming became such a pivotal part of the local economy following the construction of the Meon Valley Railway that the railway became nicknamed the "Strawberry Line". During the picking season special trains known as "strawberry specials" were laid on, carrying entire trainloads of strawberries to market.[28][36]) Likewise, bulk goods such as coal and beer could for the first time be shipped cheaply to Droxford and the surrounding villages.[37] The station also proved popular with spectators visiting the Hambledon Hunt's racecourse, approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) from the station,[35] and with people travelling to the market in Alton, a service which proved so popular that the railway offered special ticket prices on market days.[28]

First World War and inter-war decline

.jpg.webp)

On the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Britain's railway network was taken into government control. While initially there was little impact on services through Droxford, the need to prioritise military needs and the transfer of railway equipment to France caused a reduction in services on the line.[38] As the war went on, wartime shortages meant there were few goods available in the shops while labour shortages led to a rise in household incomes. Consequently, holidays increased in popularity as there was little else on which people could spend their money, causing an increase in passenger numbers on the Meon Valley railway which connected London to picturesque country villages and busy coastal resorts.[38] The increased popularity of holidays and a national shortage of rolling stock and skilled railway staff led the government to take drastic measures.[39] Fares were increased by 50 per cent, special holiday trains were abolished, along with almost all concessionary tickets, and a new intentionally slow timetable was introduced.[39] The measures were not as successful in curbing demand as the government had hoped, and passenger numbers fell by only 7 per cent.[39]

In the lengthy recession following the First World War, services on the line were further reduced.[35] A proposed doubling of the track was abandoned,[24] and trains in both directions used only a single line, the second track south of Droxford being utilised only as an extended siding.[40] Trains were reduced from four to six carriages to small sets of two carriages hauled by LSWR M7 class locomotives.[41] The 1923 absorption of the LSWR into the Southern Railway (SR) led to further economies, and around 1926 the footbridge connecting the platforms of Droxford station was removed, passengers henceforward having to cross the line on foot from the northern ends of the platforms.[35] By this time, cars and lorries were beginning to come into widespread use, providing direct competition with the railway for both goods and passenger traffic.[24][36] Although the railway continued to operate six trains a day in each direction, they remained slower than they had been in 1914.[25] With the expansion of Southampton—which already had a fast and direct service from London—as a major port, there was little need for a route from London to Gosport. In 1937 the line from London to Alton was electrified, making through trains to London no longer feasible and leaving the steam-powered Meon Valley Railway as a rural branch line.[25]

Second World War

On 3 September 1939 Britain declared war on Germany, and the Second World War began. Following the outbreak of war the Meon Valley railway remained in passenger and goods use during the day, and at night was used by troop trains carrying soldiers to Southampton to be shipped to France.[42][upper-alpha 10] Portsmouth and Gosport, both major military facilities within easy reach of German aircraft, were expected to come under severe bombardment, and many children from these towns were evacuated along the line to the villages of the Meon Valley.[42] As a potential strategic route the Meon Valley Line came under occasional bombing from German aircraft attempting to disrupt traffic to and from the Channel ports. In 1940 the station building was lightly damaged and two of the four railway cottages were destroyed by a Junkers Ju 88 aircraft, the only significant damage to Droxford station during the war.[43][44]

As the line was relatively lightly used, it was occasionally used for experimental purposes; in 1941 a special train visited Droxford hauled by an LSWR 700 class locomotive, carrying 35 Bren Gun Carriers and their associated troops, as an experiment into the feasibility of carrying troops and their equipment together. Having developed vacuum problems, the train remained in the siding at Droxford for two days, before eventually progressing to the coast.[44]

Because railway managers had proven skills in administration and of managing logistics they were in demand from the government for strategic management, and many of the managers of Britain's four railway companies were seconded to government.[45] Additionally, although railway work was a reserved occupation, large numbers of railway staff nonetheless volunteered for military service.[46][upper-alpha 11] Staff shortages and the lack of supplies caused services on the Meon Valley line to deteriorate; the maximum speeds were reduced to 10 miles per hour (16 km/h) for goods traffic and 30 miles per hour (48 km/h) for passenger trains.[43] Despite the decline in the standard of services, Droxford station remained busy. Fuel rationing had made road transport between farms and the towns largely unviable; consequently, goods and passengers going to and from the surrounding villages largely ceased to be carried by road, and instead would be taken to Droxford station for onward shipment by train.[43]

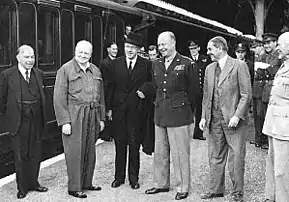

Winston Churchill

On the morning of 2 June 1944 orders were telephoned along the length of the Meon Valley Railway that it was to be kept free of trains to ensure a special train could use the route without interruption. The royal train of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway, a T9 class locomotive hauling armoured carriages, pulled into the sidings at Droxford station.[44] Troops surrounded the station and its sidings, and the local post office was ordered to let no mail other than official business leave the village.[51] Droxford's signalman Reg Gould, whose daughter had been born the previous month, was treated to a full breakfast off the ration book.[51][upper-alpha 13]

Although officially kept secret from local residents, it soon transpired that Winston Churchill had chosen the station as a secure base, to be near the coast and to the Allied command centre at Southwick House during the forthcoming Normandy landings.[51] His reason for choosing Droxford is not recorded, other than its proximity to the Channel ports; there was local speculation that the site was chosen owing to its deep cutting into which the train could be repositioned should it come under attack.[51][upper-alpha 14] Droxford also had the advantage of being overshadowed by beech trees, which obscured the view of the train.[44]

In the company of his secretary Marion Holmes, General "Pug" Ismay and South African prime minister Jan Smuts, Churchill was to remain in the carriage at Droxford for the next four days other than a few brief excursions.[51] On those occasions in which the party needed to leave the train, it would be driven the short distance from the siding to the platform, and those on board would exit through the booking hall to staff cars waiting at the exit. For reasons unknown, Churchill refused to follow this procedure, and insisted on exiting through the goods yard.[48]

.jpg.webp)

On 3 June Anthony Eden (at that time the Foreign Secretary) and Pierson Dixon visited Churchill on the train.[51] Eden was unimpressed, and was later to describe the train as a place where "it was almost impossible to conduct any business" owing to there only being one bath and one telephone, each of which was constantly in use by Churchill or Ismay.[52] A string of visits from other close confidantes of Churchill followed, including Ernest Bevin, Geoffrey William Geoffrey-Lloyd, Duncan Sandys and Arthur Tedder,[48][53] as well as fellow Commonwealth prime ministers Peter Fraser, Sir Godfrey Huggins and William Lyon Mackenzie King.[48] In addition to the meetings held on board, the train took Churchill, Bevin and Smuts to Southampton to watch invasion forces embark.[51] Churchill hosted a dinner aboard the train, at which Eden and Bevin—both considered potential successors to Churchill—discussed the possibility of working together to continue Britain's wartime coalition government in peacetime should Churchill retire.[53] Later that night Dwight Eisenhower, from his nearby base at Southwick House, decided to postpone the invasion from 5 to 6 June owing to predicted bad weather.[53]

Charles de Gaulle

Although the Allied invasion of France was only days away, Free French leader Charles de Gaulle had yet to be informed of the invasion plans. Not wishing to risk communicating with the French government in exile in Algeria about the forthcoming invasion plans, but wary of a potentially disastrous diplomatic incident should the invasion begin without French knowledge, the British cabinet had agreed to invite de Gaulle to visit England, at which time the invasion plans would be disclosed to him in person.[53] In the morning of 4 June, de Gaulle landed at RAF Northolt, to be met with a telegram from Churchill:

TOP SECRET

My dear General de Gaulle,

Welcome to these shores! Very great military events are about to take place. I should be glad if you could come to see me down here in my train, which is close to General Eisenhower's Headquarters, bringing with you one or two of your party. General Eisenhower is looking forward to seeing you again and will explain to you the military position which is momentous and imminent. If you could be here by 1.30 p.m., I should be glad to give you dejeuner and we will then repair to General Eisenhower's Headquarters. Let me have a telephone message early to know whether this is agreeable to you or not.[54]

De Gaulle was apprehensive as to why he had been invited to this unusual location. He arrived at Droxford at about 1.00 pm and was met by Anthony Eden and they walked up the track towards Churchill's siding, to be greeted with open arms by Churchill on the track. They entered the train to meet Jan Smuts and Ernest Bevin, where Churchill informed de Gaulle of the imminent invasion. De Gaulle asked Churchill how a liberated France was to be administered; Churchill told de Gaulle he would need to take it up with Franklin D. Roosevelt and that if ever he had to make a choice between France and the United States he would always side with the United States, a statement at which de Gaulle took great offence.[55]

Anthony Eden was horrified at how Churchill had handled such a sensitive meeting. He spoke to de Gaulle privately to make amends, but the relationship between de Gaulle and Churchill had been badly damaged.[55] From this point onwards de Gaulle was distrustful of the relationship between Britain and the United States, ultimately leading to a breakdown of relations between post-war Britain and France and to de Gaulle's vetoing of British membership of the European Economic Community.[56]

At 6.58 pm on 5 June, Churchill's train pulled out of Droxford and returned to London.[48] The time of his arrival at Downing Street is not recorded, but at 10.30 pm his duty typist was summoned.[57] At 16 minutes past midnight the following morning, British glider troops attacked Pegasus Bridge and the American airborne landings in Normandy began shortly after.[58]

Nationalisation

On 26 July 1945 the Labour Party won a landslide victory on a manifesto that included bringing strategic industries into public control, and on 1 January 1948 the Southern Railway became the Southern Region of the publicly owned British Railways.[59] Although still invaluable for the transport of bulk goods, the use of railways in the area fell sharply after the war. The abolition of petrol rationing in 1950 made the car far more practical than it had been,[60] and the location of Droxford station between the two villages meant that it was inconvenient for both.[60][61] Railway stations and rolling stock had suffered from poor maintenance since the outbreak of war; trains were slow and dirty, and there was an increasing number of high-profile railway accidents.[60] To address the decline, services on the Meon Valley Railway were drastically cut. Goods charges were increased, Sunday services were scrapped, and weekday passenger service was reduced to four trains per day in each direction with the last train leaving Alton at 4.30 pm, making day return travel to London impossible.[61] By this time Droxford no longer had its own stationmaster, and the stationmaster of nearby Wickham was in nominal charge of the station with Reg Daniels, Droxford's senior porter, responsible for its administration.[60]

With the railway network struggling, the British Transport Commission (BTC) proposed drastic measures. On 3 May 1954 the BTC proposed the closure of the Meon Valley Railway to passengers and the total closure of the line between Droxford and Farringdon Halt, leaving a short 3 1⁄2-mile (5.6 km) stub between Alton and Farringdon and a longer 9 3⁄4-mile (15.7 km) route between Fareham and Droxford to carry any remaining goods traffic, by this time primarily coal for J. E. Smith's coal yard near Droxford station, and agricultural produce from the area's farms.[62] For those passengers without access to cars, the BTC proposed improving bus services between Portsmouth and Meonstoke; they calculated that replacing four passenger trains per day with six buses would achieve annual savings of £38,000 (about £1,050,000 in 2021 terms[16]).[63] On 17 November 1954 the BTC announced the withdrawal of passenger services, and freight services between Droxford and Farringdon Halt, effective from 7 February 1955.[64] The BTC guaranteed that one freight train per day would run on each of the two remaining sections of the line.[65]

Closure

.jpg.webp)

As 6 February 1955, officially the last day of service, was a Sunday on which no passenger trains were due to run, the last scheduled passenger services to Droxford were those of 5 February 1955.[67] At 7.14 pm the last scheduled passenger train to stop at Droxford pulled out, arriving in Alton at 7.43 pm.[68] On 6 February 1955 a special train named The Hampshireman,[69] consisting of two locomotives hauling ten carriages, went on a circular journey leaving London Waterloo station at 9.45 am, passing through Pulborough and along the line from Pulborough to Petersfield via Midhurst which was also due to close the next day,[67] north from Fareham to Alton along the Meon Valley Railway, and back to Waterloo, passing through Droxford at about 3.20 pm without stopping.[70][71] With the station now a terminus with no need for signalling, the signal box was demolished later that year.[72]

While the goods service from Droxford was kept busy during the sugar beet harvest, there was little demand for the rest of the year, and in 1956 it was reduced to three trains a week. Despite these economies, the line remained unprofitable.[65] On 30 April 1961 the Solent Express, an excursion train chartered by the Locomotive Club of Great Britain, paid a brief visit to Droxford, the last passenger train to visit the station.[73] The Hampshire Narrow Gauge Railway Trust approached Droxford council in May 1961 with a proposal to build a narrow-gauge line along part of the disused railway between Droxford and West Meon, arguing this would bring tourists to the area, but the proposal was abandoned in 1962.[74]

.jpg.webp)

On 1 June 1961 Dr Richard Beeching became chairman of the newly formed British Railways Board, with a brief of returning the network to financial stability. The branch line to Droxford, profitable only during the sugar beet harvest, was an obvious candidate for closure. On 30 April 1962 goods service was ended on the branch, and Droxford station was formally closed.[75] Reg Gould, who by this time had been signalman for over 20 years and was the de facto manager of the station, was transferred to nearby Swanwick railway station.[76] The tracks remained in place, and were used for the storage of redundant goods wagons awaiting scrapping.[77] The short stub between Alton and Farringdon Halt remained operational by goods trains until 13 August 1968, the last part of the Meon Valley Railway to close.[75]

Post closure

Following its closure, Droxford station and the track south to Wickham were leased by the Sadler Rail Coach Company. The company's proprietor Charles Sadler Ashby had built the Pacerailer, a vehicle consisting of a bus-style body on rails, and used the line to demonstrate it to potential buyers;[78] a section was rebuilt with a 1:10 incline to demonstrate its abilities on steep gradients.[79] At the request of the Southern Locomotive Preservation Society, Ashby allowed the use of the sidings to store engines and carriages.[80] A serious problem with vandalism arose at the site when the tracks were intentionally blocked and points jammed in an effort to derail vehicles, and on 4 May 1970 the Pacerailer prototype was burned out and badly damaged.[80][upper-alpha 15] Eventually British Rail closed the Knowle junction, ending the last connection between Droxford and the railway network, and the Southern Locomotive Preservation Society abandoned the site.[79][upper-alpha 16] Hampshire County Council considered building a road along the former railway line, and in September 1972 purchased the land and leased the station building and a 4 1⁄2 miles (7.2 km) section of track at Droxford to Ashby. This effectively freed British Rail from maintaining utilities it had not used for many years.[83]

Ashby died in February 1976, by which time the tracks to Droxford had been removed. The dates are not recorded, but Ashby's test track between Droxford and Wickham was probably removed in 1975, as had been the track south of Wickham in 1974.[84] The Sadler Rail Coach Company was dissolved in December 1976, having failed to sell the Pacerailer to any railway company.[84] A similar concept, the Pacer, was successfully developed by British Rail in the 1980s.[78] Droxford station and its associated land were taken over by a driving school; the surrounding land was tarmacked and used for the training of HGV drivers.[84] In 1984 the building was sold to Colin and Elizabeth Olford, who removed the surrounding tarmac and restored the building to close to its original appearance.[66] As of 2016 it remained a private residence.[85]

Footnotes

- Although the station was officially named "Droxford", the signage on the platforms read "Droxford for Hambledon" throughout its existence.[1]

- In 1801 Droxford had a population of 1200, and neighbouring Soberton on the opposite bank of the Meon had a population of 672. By 1871 the populations of both had roughly doubled. After 1871 the population of both steadily declined until the opening of the railway, reaching lows of 1189 and 498 respectively in 1901.[5]

- Building the line to main line standards would allow high-speed express trains to run over the line from other parts of the railway network. As the new line would be the shortest route between London and the Royal Family's private terminal in the Royal Clarence Yard at Gosport, the LSWR hoped that Queen Victoria would become a regular user of the route on her journeys to and from Osborne House, generating favourable publicity for the company.[8] Victoria died in 1901, before the opening of the railway; following her death none of the royal family were interested in using Osborne House, and her successor Edward VII donated the building to the nation.[10]

- Soberton was famous for the quality of its farmland. William Cobbett, writing in 1826, described Soberton Down as "the very greenest thing that I have seen in the whole country".[12]

- Soberton was considerably wealthier than Meonstoke. The clergy of Meonstoke had long opposed the separation of Soberton and Meonstoke, owing to concerns about potential loss of income from lands in Soberton.[14]

- Prior to his becoming rector of Soberton, Morley had been the curate of Meonstoke with responsibility for Soberton for over 20 years. Although curates generally only remained in the role for a short time before moving on to better-paid and more prestigious jobs elsewhere, Morley was independently wealthy. On arriving at Soberton in 1874 he began a comprehensive programme of renovations to the dilapidated Church of St Peter and St Paul, and undertook to remain in the post until the renovation was complete.[14] Morley remained rector of Soberton until his retirement in 1920.[15] He died on 12 April 1925.[15]

- As well as compensation to the landowners, Thomas Christian, tenant farmer of the field in which the station was to be built, received a total of £248 3s 4d (about £28,000 in 2021 terms[16]) in compensation. William Davis, tenant farmer of an adjoining field of which 2 acres (0.81 ha) was sold to the LSWR, received £38 (about £4,300 in 2021 terms[16]).[15]

- To assist with the loading and unloading of goods, the goods sidings were equipped with hand-operated cranes.[23]

- Droxford's first stationmaster, Frank Wills, earned £80 (about £8,700 in 2021 terms[16]) a year at the time of opening, plus rent-free accommodation in the house. As of 1911, Wills lived in the house with his wife, mother, and six children.[26]

- The Meon Valley route was also used by naval officers travelling from London to Portsmouth. Although slower than other routes, the journey was through a more pleasant landscape and the trains were generally quieter and less crowded.[42]

- Railway workers were exempt from conscription, but those who volunteered for active service would still be accepted. Around 60,000 railway employees joined the armed forces, including around 4000 women.[47]

- This series of photographs is generally credited as having been taken at Droxford, and a copy of this picture hung in the booking office at the station. Eisenhower is not recorded as having visited Droxford and the design of the station canopy appears to differ from other photographs of the station in the period.[48] The photographs may have actually been taken during a journey to view coastal artillery sites during the 1944 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference,[49] or at Ascot station.[50]

- Reg Gould was an army conscript, released from service when it was discovered he was a qualified signalman. Ordered to Droxford as signalman, he remained at the station until its closure.[42]

- Churchill was keen to witness the Normandy landings in person. He was only dissuaded from viewing the invasion from the deck of a warship in the English Channel through the intervention of Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff.[52]

- Ashby was in advanced negotiations to reopen the line between Cowes and Ryde on the Isle of Wight using Pacerailers. It was alleged that one of the Isle of Wight's bus companies was behind the vandalism and arson at Droxford.[81]

- The Southern Locomotive Preservation Society relocated their stock to Liss, where a group of enthusiasts were attempting to reopen the Longmoor Military Railway. This scheme failed soon afterwards. Their collection eventually became part of the Bluebell Railway.[82]

References

- Buttrey 2012, p. 15.

- "River Meon". Visit Hampshire. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- Buttrey 2012, pp. 8–9.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 8.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 9.

- Stone 1983, p. 4.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 10.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 11.

- Stone 1983, p. 6.

- Struthers 2004, p. 39.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 12.

- Cobbett, William (4 November 1826). "Rural Ride From Weston, near Southampton, to Kensington". Cobbett's Weekly Political Register. London: W. Cobbett. 60 (6): 341.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 17.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 16.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 18.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 19.

- Stone 1983, p. 27.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 89.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 88.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 20.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 23.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 24.

- Stone 1983, p. 44.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 52.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 28.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 37.

- Stone 1983, p. 42.

- Stone 1983, p. 36.

- Stone 1983, p. 28.

- Stone 1983, p. 7.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 25.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 27.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 39.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 50.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 42.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 43.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 47.

- Wolmar 2007, p. 219.

- Stone 1983, p. 56.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 49.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 53.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 54.

- Stone 1983, p. 69.

- Wolmar 2007, p. 255.

- Wolmar 2007, p. 254.

- Wolmar 2007, pp. 254–55.

- Stone 1983, p. 70.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 55.

- Catford, Nick. "Disused Stations: Droxford Station". Disused Stations. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 56.

- Hastings, Max (2010). "Overlord – Winston's War: Churchill, 1940–1945". Erenow. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 57.

- Gilbert 1986, p. 788.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 58.

- Sy-Wonyu 2003, p. 218.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 59.

- Beevor 2009, pp. 52–53.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 61.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 63.

- Stone 1983, p. 94.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 64.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 65.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 67.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 70.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 91.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 68.

- Stone 1983, p. 98.

- Buttrey 2012, pp. 68–70.

- Stone 1983, p. 95.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 7.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 73.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 79.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 81.

- Stone 1983, p. 104.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 71.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 80.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 83.

- Stone 1983, p. 106.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 85.

- Buttrey 2012, pp. 85–86.

- Stone 1983, p. 108.

- Buttrey 2012, pp. 84–85.

- Buttrey 2012, p. 90.

- Hind, Bob (25 June 2016). "End of the Line for Droxford Station". The News. Portsmouth: Portsmouth Publishing & Printing. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

Bibliography

- Beevor, Antony (2009). D-Day: The Battle for Normandy. New York; Toronto: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-02119-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buttrey, Pam (2012). A History of Droxford Station. Corhampton: Noodle Books. ISBN 978-1-906419-93-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gilbert, Martin (1986). Winston S Churchill. VII: Road to Victory 1941–1945. London: Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-434130-17-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stone, R. A. (1983). The Meon Valley Railway. Southampton: Kingfisher Railway Productions. ISBN 978-0-946184-04-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Struthers, Jane (2004). Royal Palaces of Britain. London: New Holland Publishers (UK) Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84330-733-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sy-Wonyu, Aïssatou (2003). The "Special Relationship". Mont-Saint-Aignan, France: Presses universitaires de Rouen et du Havre. ISBN 978-2-877758-62-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolmar, Christian (2007). Fire & Steam. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-84354-630-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Preceding station | Disused railways | Following station | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| West Meon Line and station closed |

British Rail Southern Region Meon Valley Railway line |

Wickham Line and station closed |