Divine (performer)

Harris Glenn Milstead (October 19, 1945 – March 7, 1988), better known by his stage name Divine, was an American actor, singer, and drag queen. Closely associated with the independent filmmaker John Waters, Divine was a character actor, usually performing female roles in cinematic and theatrical productions, and adopted a female drag persona for his music career.

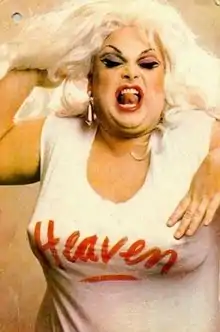

Divine | |

|---|---|

Divine in a publicity photograph from the 1980s | |

| Born | Harris Glenn Milstead October 19, 1945 Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Died | March 7, 1988 (aged 42) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Prospect Hill Cemetery (Towson, Maryland) |

| Occupation | Actor, singer, drag queen |

| Years active | 1966–1988 |

| Website | divineofficial |

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, to a conservative middle-class family, Milstead developed an early interest in drag while working as a women's hairdresser. By the mid-1960s he had embraced the city's countercultural scene and befriended Waters, who gave him the name "Divine" and the tagline of "the most beautiful woman in the world, almost." Along with his friend David Lochary, Divine joined Waters' acting troupe, the Dreamlanders, and adopted female roles for their experimental short films Roman Candles (1966), Eat Your Makeup (1968), and The Diane Linkletter Story (1969). Again in drag, he took a lead role in both of Waters' early full-length movies, Mondo Trasho (1969) and Multiple Maniacs (1970), the latter of which began to attract press attention for the group. Divine next starred in Waters' Pink Flamingos (1972), which proved a hit on the U.S. midnight movie circuit, became a cult classic, and established Divine's fame within the American counterculture.

After starring as the lead role in Waters' next film, Female Trouble (1974), Divine moved on to theater, appearing in several avant-garde performances alongside San Francisco drag collective, The Cockettes. He followed this with a performance in Tom Eyen's play Women Behind Bars and its sequel, The Neon Woman. Continuing his cinematic work, he starred in two more of Waters' films, Polyester (1981) and Hairspray (1988), the latter of which represented his breakthrough into mainstream cinema and for which he was nominated for the Independent Spirit Award for Best Supporting Male. Independent of Waters, he also appeared in a number of other films, such as Lust in the Dust (1985) and Trouble in Mind (1985), seeking to diversify his repertoire by playing male roles. In 1981, Divine embarked on a career in the disco industry by producing a number of Hi-NRG tracks, most of which were written by Bobby Orlando. He achieved international chart success with hits like "You Think You're a Man", "I'm So Beautiful", and "Walk Like a Man", all of which were performed in drag. Having struggled with obesity throughout his life, he died from cardiomegaly, shortly after the release of Hairspray.

Described by People magazine as the "Drag Queen of the Century",[1] Divine has remained a cult figure, particularly within the LGBT community, and has provided the inspiration for fictional characters, artworks, and songs. Various books and documentary films devoted to his life have also been produced, including Divine Trash (1998) and I Am Divine (2013).

Early life

Youth: 1945–1965

Harris Glenn Milstead was born on October 19, 1945, at the Women's Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.[3] His father, Harris Bernard Milstead (May 1, 1917 – March 4, 1993), after whom he was named, had been one of seven children born in Towson, Maryland to a plumber who worked for the Baltimore City Water Department.[4] Divine's mother, Frances Milstead (née Vukovich; April 12, 1920 – March 24, 2009), was one of fifteen children born to an impoverished Serb immigrant couple who had grown up near Zagreb (in today's Croatia) before moving to the United States in 1891.[5][6] When she was 16, Frances moved to Baltimore where she worked at a diner in Towson, here meeting Harris, who was a regular customer. Entering into a relationship, they were married in 1938 before both gaining employment working at the Black & Decker factory in Towson. Due to his problems with muscular dystrophy, Harris was not required to fight for the U.S. armed forces in the Second World War, and instead Harris and Frances worked throughout the war in what they saw as "good jobs".[7] Attempting to conceive a child, Frances suffered two miscarriages in 1940 and 1943.[6][8]

By the time of Divine's birth in 1945, the Milsteads were relatively wealthy and socially conservative Baptists.[9] Describing his upbringing, Divine recollected: "I was an only child in, I guess, your upper middle-class American family. I was probably your American spoiled brat."[9] His parents lavished almost anything that he wanted upon him, including food, and he became overweight, a condition he lived with for the rest of his life.[10] Divine preferred to use his middle name, Glenn, to distinguish himself from his father, and was referred to as such by his parents and friends.[11]

At age 12, Divine and his parents moved to Lutherville, a Baltimore suburb, where he attended Towson High School, graduating in 1963.[12][13] Bullied because of his weight and perceived effeminacy,[14] he later reminisced that he "wasn't rough and tough" but instead "loved painting and I always loved flowers and things."[12] Due to this horticultural interest, at 15 he took a part-time job at a local florist's shop.[15] Several years later, he went on a diet that enabled him to drop in weight from 180 to 145 pounds (82 to 66 kg), giving him a new sense of confidence.[15] When he was 17, his parents sent him to a psychiatrist, where he first realized his sexual attraction to men as well as women, something then taboo in conventional American society.[16] He helped out at his parents' day care business, for instance dressing up as Santa Claus to entertain the children at Christmas time.[17] In 1963, he began attending the Marinella Beauty School, where he learned hair styling and, after completing his studies, gained employment at a couple of local salons, specializing in the creation of beehives and other upswept hairstyles.[16][18] Milstead eventually gave up his job and for a while was financially supported by his parents, who catered to his expensive taste in clothes and cars. They reluctantly paid the many bills that he ran up financing lavish parties where he dressed in drag as his favorite celebrity, actress Elizabeth Taylor.[19][20]

John Waters and Divine's first films: 1966–1968

Milstead developed a large coterie of friends, among them David Lochary, who became an actor and costar in several of Divine's later films.[21][22] In the mid-1960s, Milstead befriended John Waters through their mutual friend Carol Wernig; Waters and Milstead were the same age and from the same neighborhood, and both embraced Baltimore's countercultural and underground elements.[6][23][24] Along with friends like Waters and Lochary, Milstead began hanging out at a beatnik bar in downtown Baltimore named Martick's, where they associated with hippies and smoked marijuana, bonding into what Waters described as "a family of sorts".[23] Waters gave his friends new nicknames, and it was he who first called Milstead "Divine". Waters later remarked that he had borrowed the name from a character in Jean Genet's novel Our Lady of the Flowers (1943), a controversial book about homosexuals living on the margins of Parisian society, which Waters – himself a homosexual – was reading at the time.[25] Waters also introduced Divine as "the most beautiful woman in the world, almost", a description widely repeated in ensuing years.[25]

— Divine, 1973.[26]

Waters was an aspiring filmmaker, intent on making "the trashiest motion pictures in cinema history".[27] Many of his friends, a group which came to be known as "the Dreamlanders" (and who included Divine, Lochary, Mary Vivian Pearce and Mink Stole), appeared in some of his low-budget productions, filmed on Sunday afternoons.[27] Following the production of his first short film, Hag in a Black Leather Jacket (1964), Waters began production of a second work, Roman Candles (1966). This film was influenced by the pop artist Andy Warhol's Chelsea Girls (1966), and consisted of three 8-millimeter movies played simultaneously side by side. Roman Candles was the first film to star Divine, in this instance in drag as a smoking nun. It featured the Dreamlanders modeling shoplifted clothes and performing various unrelated activities.[27][28][29] Being both a short film and of an avant-garde nature, Roman Candles never received widespread distribution, instead holding its premier at the annual Mt. Vernon Flower Mart in Baltimore, which had become popular with "elderly dames, young faggots and hustlers, and of course a whole bunch of hippies".[30] Waters went on to screen it at several local venues alongside Kenneth Anger's short film Eaux d'Artifice (1953).[30]

Waters followed Roman Candles with a third short film, Eat Your Makeup (1968), in which Divine once more wore drag, this time to portray a fictionalized version of Jackie Kennedy, the widow of recently assassinated U.S. President John F. Kennedy. In the film, she turns to kidnapping models and forcing them to eat their own makeup.[31][32] Divine kept his involvement with Waters and these early underground films a secret from his conservative parents, believing that they would not understand them or the reason for his involvement in such controversial and bad-taste films; they would not find out about them for many years.[33][34] Divine's parents had bought him his own beauty shop in Towson, hoping that the financial responsibility would help him to settle down in life and stop spending so extravagantly. While agreeing to work there, he refused to be involved in owning and managing the establishment, leaving that to his mother.[35] Not long after, in the summer of 1968, he moved out of his parental home, renting his own apartment.[36]

The Diane Linkletter Story, Mondo Trasho, and Multiple Maniacs: 1969–1970

Divine appeared in Waters's next short film, The Diane Linkletter Story (1969), which was initially designed to be a test for a new sound camera. A black comedy that carried on in Waters's tradition of making "bad taste" films to shock conventional American society, The Diane Linkletter Story was based upon the true story of Diane Linkletter, the daughter of media personality Art Linkletter, who had committed suicide earlier that year. Her death had led to a flurry of media interest and speculation, with various sources erroneously claiming that she had done so under the influence of the psychedelic LSD. Waters's dramatized version starred Divine in the leading role as the teenager who rebels against her conservative parents after they try to break up her relationship with hippie boyfriend Jim, before consuming a large quantity of LSD and committing suicide. Although screened at the first Baltimore Film Festival, the film was not publicly released at the time, largely for legal reasons.[31][37]

Soon after the production of The Diane Linkletter Story, Waters began filming a full-length motion picture, Mondo Trasho, starring Divine as one of the main characters, an unnamed blonde woman who drives around town and runs over a hitchhiker.[38][39] In one scene, an actor was required to walk along a street naked, which was a crime in the state of Maryland at the time, leading to the arrest of Waters and most of the actors associated with the film; Divine escaped, having speedily driven away from the police when they arrived to carry out the arrests.[40] In their review of the film, the Los Angeles Free Press exclaimed that "The 300-pound (140 kg) sex-symbol Divine is undoubtedly some sort of discovery."[41]

In 1970, Divine abandoned work as a hairdresser, opening up a vintage clothing store in Provincetown, Massachusetts using his parents' money. Opening in 1970 as "Divine Trash", the store sold items that Divine had purchased in thrift stores, flea markets and garage sales, although it had to move from its original location after he had failed to obtain a license from the local authorities.[31][42] Realizing that this venture was not financially viable, Divine sold off his stock at very low prices. In the hope of raising some extra money, he sold the furniture of his rented, furnished apartment, leading the landlady to put out a warrant for his arrest.[43][44] He evaded the local police by traveling to San Francisco, California, a city which had a large gay subculture that attracted Divine, who was then embracing his homosexuality.[45]

In 1970, Divine played the role of Lady Divine, the operator of an exhibit known as The Cavalcade of Perversion who turns to murdering visitors in Waters's film Multiple Maniacs. The film contained several controversial scenes, notably one which involved Lady Divine masturbating using a rosary while sitting inside a church. In another, Lady Divine kills her boyfriend and proceeds to eat his heart; in actuality, Divine bit into a cow's heart which had gone rotten from being left out on the set all day. At the end of the film, Lady Divine is raped by a giant lobster named Lobstora, an act that drives her into madness; she subsequently goes on a killing spree in Fell's Point before being shot down by the National Guard.[46][47][48] Due to its controversial nature, Waters feared that the film would be banned and confiscated by the Maryland Censor Board, so avoided their jurisdiction by only screening it at non-commercial venues, namely rented church premises.[49] Multiple Maniacs was the first of Waters's films to receive widespread attention, as did Divine; KSFX remarked that "Divine is incredible! Could start a whole new trend in films."[46]

Rise to fame

Pink Flamingos: 1971–1972

Following his San Francisco stay, Divine returned to Baltimore and participated in Waters's next film Pink Flamingos. Designed by Waters to be "an exercise in poor taste,"[50] the film featured Divine as Babs Johnson, a woman who claims to be "the filthiest person alive" and who is forced to prove her right to the title from challengers, Connie (Mink Stole) and Raymond Marble (David Lochary).[51] In one scene, the Marbles send Babs a turd in a box as a birthday present, and in order to enact this scene, Divine defecated into the box the night before.[52] Filmed in a hippie commune in Phoenix, Maryland, the cast members spent much of the time smoking cigarettes and marijuana and taking amphetamines. All of the scenes had been heavily rehearsed beforehand.[53] The final scene in the film proved particularly infamous, involving Babs eating fresh dog feces; Divine later told a reporter, "I followed that dog around for three hours just zooming in on its asshole," waiting for it to empty its bowels so that they could film the scene.[54] The scene became one of the most notable moments of Divine's acting career, and he later complained of people thinking that "I run around doing it all the time. I've received boxes of dog shit – plastic dog shit. I have gone to parties where people just sit around and talk about dog shit because they think it's what I want to talk about."[54] In reality, he remarked, he was not a coprophile but only ate excrement that one time because it was in the script.[54][55]

The film premiered in late 1972 at the third Annual Baltimore Film Festival, held on the campus of the University of Baltimore, where it sold out tickets for three successive screenings; the film aroused particular interest among underground cinema fans following the success of Multiple Maniacs, which had begun to be screened in New York City, Philadelphia, and San Francisco.[56] Being picked up by the small independent company New Line Cinema, Pink Flamingos was distributed to Ben Barenholtz, the owner of the Elgin Theater in New York City. At the Elgin Theater, Barenholtz had been promoting the midnight movie scene, primarily by screening Alejandro Jodorowsky's acid western film El Topo (1970). Barenholtz felt that being of an avant-garde nature, Pink Flamingos would fit in well with this crowd, screening it at midnight on Friday and Saturday nights.[57][58] The film soon gained a cult following at the Elgin Theatre. Barenholtz characterized its early fans as primarily being "downtown gay people, more of the hipper set," but after a while he noted that this group broadened, with the film becoming popular with "working-class kids from New Jersey who would become a little rowdy".[59] Many of these cult cinema fans learned all of the film's lines, reciting them at the screenings, a phenomenon which became associated with another popular midnight movie of the era, The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975).[59]

While keeping his involvement with Waters's underground filmmaking a secret from his parents, Divine continued relying on them financially, charging them for expensive parties that he held and writing bad checks. After he charged them for a major repair to his car in 1972, his parents confiscated it from him and told him that they would not continue to support him in such a manner. In retaliation, he came by their house the following day, collected his two pet dogs and then disappeared, not seeing or speaking with them for the next nine years. Instead, he sent them over fifty postcards from across the world, informing them that he was fine, but on none did he leave a return address.[60] Frances and Harris Milstead retired soon after and moved to Florida at the advice of Harris's doctor, who prescribed the southern state's warmer weather as being beneficial for Harris's muscular dystrophy.[61]

Theater work and Female Trouble: 1973–1978

When the filming of Pink Flamingos finished, Divine returned to San Francisco, where he and Mink Stole starred in a number of small-budget plays at the Palace Theater as part of drag troupe The Cockettes, including Divine and Her Stimulating Studs, Divine Saves the World, Vice Palace, Journey to the Center of Uranus and The Heartbreak of Psoriasis.[62][63][64] It was here that he first met androgynous performer Sylvester.[65] Divine purchased a house in Santa Monica, which he furnished to his expensive tastes.[66] On visits to Washington D.C. during the early 1970s, Divine and Waters attended the city's balls that were frequented by LGBT African-Americans. Here, Waters encouraged Divine's drag persona to become more outrageous, exposing her overweight stomach and carrying weapons. He later commented that he wanted Divine to become "the Godzilla of drag queens",[67] a direct confrontation with the majority of Euro-American drag queens who wanted to be Miss America.[67][68] In his private life, Divine became the godfather of Brook Yeaton, the son of his friends Chuck Yeaton and Pat Moran; Brook and Divine remained very close until Divine's death.[69]

In 1974, Divine returned to Baltimore to film Waters's next motion picture, Female Trouble, in which he played the lead role. Divine's character, teenage delinquent Dawn Davenport, embraces the idea that crime is art and is eventually executed in the electric chair for her violent behavior.[70][71] Waters claimed that the character of Dawn had been partly based on the mutual friend who had introduced him to Divine, Carol Wernig, while the costumes and make-up were once more designed by Van Smith to create the desired "trashy, slutty look."[72] In the film, Divine did his own stunts, including the trampoline scene, for which he had to undertake a number of trampolining lessons.[73] Divine also played his first on-screen male role in the film, Earl Peterson, and Waters included a scene during which these two characters had sexual intercourse as a joke on the fact that both characters were played by the same actor. Female Trouble proved to be Divine's favorite of his films, because it both allowed him to develop his character and to finally play a male role, something he had always felt important because he feared being typecast as a female impersonator.[73][74][75] Divine was also responsible for singing the theme tune for Female Trouble, although it was never released as a single.[76] Divine remained proud of the film, although it received a mixed critical reception.[77]

In 1977, Divine co-starred in the revue Restless Underwear, alongside Canadian rock band Rough Trade, which played at Massey Hall in Toronto. In 1980, the revue appeared at the Beacon Theater on Manhattan's Upper West Side. Bernard Jay, Divine's manager, said that it was a "gigantic disaster," as Divine did not have as large a part in the revue as audience members expected.[78]

Divine was unable to appear in Waters's next feature, Desperate Living (1977), despite the fact that the role of Mole McHenry had been written for him. This was because he had returned to working in the theater, this time taking the role of the scheming prison matron Pauline in Tom Eyen's comedy Women Behind Bars. Performed in New York City's Truck and Warehouse Theater, the play proved popular and was later taken to London's Whitehall Theater next to Trafalgar Square. Containing a new cast, it proved less successful than it had in New York.[79][80][81] It was in this city that Divine met a group of people whom he would come to know as his "London family": fashion designer Zandra Rhodes, photographer Robyn Beeche, sculptor Andrew Logan and the latter's partner, Michael Davis.[82] While in London in 1978, Divine attended as the guest of honour at the fourth Alternative Miss World pageant, a "mock" event founded by Logan in 1972 in which "drag queens" – including men, women and children – competed for the prize. The event was filmed by director Richard Gayer, whose subsequent film, entitled Alternative Miss World, premiered at the Odeon in London's Leicester Square as well as featuring at the Cannes Film Festival, both events which were attended by Divine.[83]

Impressed with Divine's performance in Women Behind Bars, playwright Tom Eyen decided to write a new play that would feature him in a starring role. The result was The Neon Woman, a story set in 1962 featuring Divine as Flash Storm, the female owner of a Baltimore strip club. It played at the Hurrah! club in New York City before moving on to the Alcazar Theatre in San Francisco. Divine remained very proud of the work, seeing it as evidence that his acting skills were coming to wider recognition, and his performances were attended by such celebrities as Eartha Kitt, Elton John, and Liza Minnelli.[84][85][86] It was during the New York leg of the play's tour that Divine befriended Jay Bennett; they subsequently began renting an apartment together on 58th Street. In the city, Divine assembled a group of friends that came to be known as his "New York family": designer Larry LeGaspi, makeup artist Conrad Santiago, Vincent Nasso, and dresser Frankie Piazza. While there, he frequented the famous club Studio 54, having a love of partying and club culture.[87]

Early disco work and Polyester: 1979–1983

Divine eventually decided to abandon his agent, Robert Hussong, and replace him with his English friend Bernard Jay. Jay suggested that with his love of clubs, Divine could obtain work performing in them; as a result, Divine first appeared in 1979 at a gay club in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where his unscripted act included shouting "fuck you" repeatedly at the audience and then getting into a fight with another drag queen, a gimmick that proved popular with the club's clientele. Subsequently, he saw the commercial potential of including disco songs in with his act and, with Tom Eyen and composer Henry Krieger, created "Born to be Cheap" in 1981.[88][89] In 1981 Divine appeared in John Waters's next film, Polyester, starring as Francine Fishpaw. Unlike earlier roles, Fishpaw was not a strong female but a meek and victimized woman who falls in love with her dream lover, Todd Tomorrow, played by Tab Hunter. In real life, tabloid publications claimed a romantic connection between them, an assertion both denied.[90][91] The film was released in "Odorama," accompanied by "scratch 'n' sniff" cards for the audience to smell at key points in the film.[92] Soon after Polyester, Divine auditioned for a male role in Ridley Scott's upcoming science-fiction film Blade Runner. Even though Scott thought Divine unsuitable for the part, he claimed to be enthusiastic about Divine's work and was very interested in including him in another of his films, but ultimately this never came about.[93]

That same year, Divine decided to get back in contact with his estranged parents. His mother had learned of his cinematic and disco career after reading an article about the films of John Waters in Life magazine, and had gone to see Female Trouble at the cinema, but had not felt emotionally able to get back in contact with her son until 1981. She got a friend to hand Divine a note at one of his concerts, leading Divine to telephone her, and the family was subsequently reunited.[94] The relationship was mended, and Divine bought them lavish gifts and informed them of how wealthy he was. In fact, according to his manager Bernard Jay, he was already heavily in debt due to his extravagant spending.[95] In 1982, he then joined forces with young American composer Bobby Orlando, who wrote a number of Hi-NRG singles for Divine, including "Native Love (Step By Step)," "Shoot Your Shot", and "Love Reaction". To help publicize these singles, which proved to be successful in many discos across the world, Divine went on television shows like Good Morning America, as well as on a series of tours in which he combined his musical performances with comedic stunts and routines that often played up to his characters' stereotype of being "trashy" and outrageous.[96][97] Throughout the rest of the 1980s, Divine took his musical performances on tour across the world, attaining a particularly large following in Europe.[98][99]

Later life

Later disco work, Lust in the Dust, and Hairspray: 1984–1988

Divine's career as a disco singer continued and his records had sold well, but he and his management felt that they were not receiving their share of the profits. They went to court against Orlando and his company, O-Records, and successfully nullified their contract. After signing with Barry Evangeli's company, InTune Music Limited, Divine released several new disco records, including "You Think You're A Man" and "I'm So Beautiful", which were both co-produced by Pete Waterman of the then-up-and-coming UK production team of Stock Aitken Waterman.[100] In the United Kingdom, Divine sang his hit "You Think You're A Man" – a song which he had dedicated to his parents – on BBC television show Top of the Pops. He gained a devout follower, Briton Mitch Whitehead, a man who declared himself Divine's "number 1 fan", tattooing himself with images of his idol and eventually aiding Bernard Jay in setting up for Divine's show onstage.[101] In London, Divine also befriended drag comedy act Paul O'Grady, with Jay helping O'Grady obtain his first bookings in the U.S.[102]

The next Divine film, Lust in the Dust (1985), reunited him with Tab Hunter and was Divine's first film not directed by John Waters. Set in the Wild West during the nineteenth century, the movie was a sex comedy that starred Divine as Rosie Velez, a promiscuous woman who works as a singer in saloons and competes for the love of Abel Wood (Tab Hunter) against another woman. A parody of the 1946 western Duel in the Sun, the film was a critical success, with Divine receiving praise from a number of reviewers.[103][104] Divine followed this production with a very different role, that of gay male gangster Hilly Blue in Trouble in Mind (1985). The script was written with Divine in mind. Although not a major character in the film, Divine had been eager to play the part because he wished to perform in more male roles and leave behind the stereotype of simply being a female impersonator. Reviews of the film were mixed, as were the evaluations of Divine's performance.[105][106]

After finishing his work on Trouble in Mind, Divine again became involved with a John Waters project, the film Hairspray (1988). Set in Baltimore during the 1960s, Hairspray revolved around self-proclaimed "pleasantly plump" teenager Tracy Turnblad as she pursues stardom as a dancer on a local television show and rallies against racial segregation. As he had in Waters's earlier film Female Trouble, Divine took on two roles in the film, one of which was female and the other male. The first of these, Edna Turnblad, was Tracy's loving mother; Divine later noted that with this character he could not be accurately described as a drag queen, proclaiming "What drag queen would allow herself to look like this? I look like half the women from Baltimore."[107] His second character in the film was that of the racist television station owner Arvin Hodgepile. In one interview, Divine admitted that he had hoped to play both the role of mother and daughter in Hairspray, but that the producers had been "a bit leery" and chose Ricki Lake for the latter role instead.[108] Divine went on to state his opinion on Lake, jokingly telling the interviewer that "She is nineteen and delightful. I hate her."[108] In reality they had become good friends while working together on set.[109] Reviews of the film were predominantly positive, with Divine in particular being singled out for praise; several commentators expressed their opinion that the film marked Divine's breakthrough into mainstream cinema.[110] He subsequently took his mother to the film's premier in the Miami Film Festival before she once more accompanied him to the Baltimore premier, this time also with several of his other relatives. After the screening, a party was held at the Baltimore Museum of Art, where Frances Milstead granted an impromptu interview to the English film critic Jonathan Ross, a friend and fan of Divine's.[111]

Divine's final film role was in the low-budget comedy horror Out of the Dark, filmed and produced in Los Angeles with the same crew as Lust in the Dust. Appearing in only one scene within the film, he played the character of Detective Langella, a foul-mouthed policeman investigating the murders of a killer clown. Out of the Dark was released the year after Divine's death.[112] Divine had become a well-known celebrity throughout the 1980s, appearing on American television chat shows such as Late Night with David Letterman, Thicke of the Night, and The Merv Griffin Show to promote both his music and his film appearances. Divine-themed merchandise was produced, including greeting cards and The Simply Divine Cut-Out Doll Book. Portraits of Divine were painted by several famous artists, including David Hockney and Andy Warhol, both of whom were known for their works which dealt with popular culture.[113]

Death: 1988

On March 7, 1988, three weeks after Hairspray was released nationwide, Divine was staying at the Regency Plaza Suites Hotel in Los Angeles. He was scheduled to tape a guest appearance the following day as Uncle Otto on the Fox network's television series Married... with Children in the second season wrap-up episode.[6][114] After spending all day at Sunset Gower Studios for rehearsals, Divine returned to his hotel that evening, where he dined with friends at the hotel restaurant before returning to his room. Shortly before midnight, he died in his sleep, at age 42, of heart failure.[115] His body was discovered by Bernard Jay the following morning, who then sat with the body for the next six hours, alongside three of Divine's other friends. They contacted Thomas Noguchi, the Chief Coroner for the County of Los Angeles, who arranged for removal of the body; Divine's friends were able to prevent the press from taking any photographs of the body as it was being carried out of the hotel.[116][117]

Divine's body was flown back to Maryland and taken to Ruck's Funeral Home in Towson, where a casket was obtained for him. The funeral took place at Prospect Hill Cemetery, where a crowd of hundreds had assembled to pay their respects.[118] The ceremony was conducted by Leland Higginbotham, who had baptized Divine into the Christian faith many years before. John Waters gave a speech and was one of the pallbearers who then carried the coffin to its final resting place, next to the grave of Divine's grandmother. Many flowers were left at the grave, including a wreath sent by actress Whoopi Goldberg, which bore the remark "See what happens when you get good reviews."[119][120] Following the funeral, a tribute was held at the Baltimore Governor's Mansion.[121] In the ensuing weeks, the Internal Revenue Service confiscated many of Divine's possessions and auctioned them off, as restitution for unpaid taxes.[122]

Drag persona and performance

Audience: "Ten dollars."

Divine: "Well now, that's eight dollars to see the show – and two dollars to fuck me right after. All line up outside the dressing room and I'll be here till Christmas!"

An example of Divine's banter with his audience[123]

After developing a name for himself as a female impersonator known for "trashy" behavior in his early John Waters films, Divine capitalized on this image by appearing at his musical performances in his drag persona. In this role, he was described by his manager Bernard Jay, as displaying "Trash. Filth. Obscenity. In bucket-loads".[124] Divine described his stage performances as "just good, dirty fun, and if you find it offensive, honey, don't join in."[123] As a part of his performance, he constantly swore at the audience, often using his signature line of "fuck you very much", and at times got audience members to come onstage, where he would fondle their buttocks, groins, and breasts.[125] Divine and his stage act proved particularly popular among gay audiences, and he appeared at some of the world's biggest gay clubs, such as Central London's Heaven. According to Divine's manager Bernard Jay, this was not because Divine himself was gay, but because the gay community "openly and proudly identified with the determination of the female character Divine".[126]

Divine became increasingly known for outlandish stunts onstage, each time trying to outdo what he had done before. At one performance in London's Hippodrome coinciding with American Independence Day, Divine rose up from the floor on a hydraulic lift, draped in the American flag, and declared: "I'm here representing Freedom, Liberty, Family Values, and the fucking American Way of Life."[127] When he performed at the London Gay Pride parade, he sang on the roof of a hired pleasure boat that floated down the Thames past Jubilee Gardens.[128] At a performance Divine gave at the Hippodrome in the last year of his life, he appeared onstage riding an infant elephant which had been hired for the occasion.[129][130] Divine was nevertheless not happy with being known primarily for his drag act, and told an interviewer that "my favorite part of drag is getting out of it. Drag is my work clothes. I only put it on when someone pays me to",[131] a view he echoed to his friends.[86][132]

Personal life

During his childhood and adolescence, Divine was called "Glenn" by his friends and family; as an adult, he used the stage name "Divine" as his personal name, telling one interviewer that both "Divine" and "Glenn Milstead" were "both just names. Glenn is the name I was brought up with, Divine is the name I've been using for the past 23 years. I guess it's always Glenn and it's always Divine. Do you mean the character Divine or the person Divine? You see, it gets very complicated. There's the Divine you're talking to now and there's the character Divine, which is just something I do to make a living. She doesn't really exist at all."[133] At one point he had the name "Divine" officially recognized, as it appeared on his passport, and in keeping with his personal use of the name, his close friends nicknamed him "Divy".[134]

Divine considered himself to be male, and was not transgender or transsexual.[135] He was gay, and during the 1980s had an extended relationship with a married man named Lee L'Ecuyer, who accompanied him almost everywhere that he went.[136] They later separated, and Divine went on to have a brief affair with gay porn star Leo Ford, which was widely reported upon by the gay press.[137] According to his manager Bernard Jay, Divine regularly engaged in sexual activities with young men that he would meet while on tour, sometimes becoming infatuated with them; in one case, he met a young man in Israel whom he wanted to bring back to the United States, but was prevented from doing so by Jay.[138] This image of promiscuity was disputed by his friend Anne Cersosimo, who claimed that Divine never exhibited such behavior when on tour.[139] Divine initially avoided informing the media about his sexuality, even when questioned by interviewers, and would sometimes hint that he was bisexual, but in the latter part of the 1980s changed this attitude and began being open about his homosexuality.[140] Nonetheless, he avoided discussing gay rights, partially at the advice of his manager, realizing that it would have had a negative effect on his career.[141]

Divine's mother, Frances Milstead, remarked that while Divine "was blessed with many talents and abilities, he could be very moody and demanding."[142] She noted that while he was "incredibly kind and generous", he always wanted to get things done the way that he wanted, and would "tune you out if you displeased him."[142] She noted that in most interviews, he came across as "a very shy and private person".[143] Divine's Dutch friends gave him two bulldogs in the early 1980s, on which he doted, naming them Beatrix and Claus after Queen Beatrix and her husband Prince Claus of the Netherlands. On numerous occasions he would have his photograph taken with them and sometimes use these images for record covers and posters.[144] Divine suffered from problems with obesity from childhood, caused by his love of food, and in later life his hunger was increased by his daily use of marijuana, an addiction that he publicly admitted to.[145][146] According to Bernard Jay, in Divine's final years, when his disco career was coming to an end and he was struggling to find acting jobs, he felt suicidal and threatened to kill himself on several occasions.[147]

Legacy and influence

The New York Times said of Milstead's 1980s films: "Those who could get past the unremitting weirdness of Divine's performance discovered that the actor/actress had genuine talent, including a natural sense of comic timing and an uncanny gift for slapstick."[148] In a letter to the newspaper, Paul Thornquist described him as "one of the few truly radical and essential artists of the century... [who] was an audacious symbol of man's quest for liberty and freedom."[149] People magazine described him as "the Goddess of Gross, the Punk Elephant, the Big Bad Mama of the Midnight Movies... [and] a Miss Piggy for the blissfully depraved."[1] Following his death, fans of Divine visited Prospect Hill Cemetery to pay their respects. In what has become a tradition, fans have been known to leave makeup, food, and graffiti on his grave in memoriam; Waters claims that some fans have sexual intercourse on his grave, which he believes Divine would love.[122][148]

Divine has left an influence on a number of musicians. During the mid-1980s, the androgynous performer Sylvester decorated the powder room of his San Francisco home with Divine memorabilia.[65] Anohni of the band Antony and the Johnsons wrote a song about Divine which was included in the group's self-titled debut album, released in 1998. The song, titled "Divine," was an ode to the actor, who was one of Anohni's lifelong heroes. Her admiration is expressed in the lines: "He was my self-determined guru" and "I turn to think of you/Who walked the way with so much pain/Who holds the mirror up to fools."[150] In 2008, Irish electronic singer Róisín Murphy paid homage to Divine in the music video for her song "Movie Star" by reenacting the attack by Lobstora from Multiple Maniacs.[151]

Divine was an inspiration for Ursula the Sea Witch, the villain in the 1989 Disney animated film The Little Mermaid.[152] Due to Divine's portrayal of Edna Turnblad in the original comedy-film version of Hairspray, later musical adaptations of Hairspray have commonly placed male actors in the role of Edna, including Harvey Fierstein and others in the 2002 Broadway musical, and John Travolta in the 2007 musical film. A 12-foot (4 m) tall statue in the likeness of Divine by Andrew Logan can be seen on permanent display at The American Visionary Art Museum in Divine's hometown of Baltimore.[153] I Am Divine, a feature documentary on the life of Divine, was premiered at the 2013 South by Southwest film festival, and had its Baltimore premiere within Maryland Film Festival. It is produced and directed by Jeffrey Schwarz of the Los Angeles-based production company Automat Pictures. In August 2015, a play based on the final day of Divine's life, Divine/Intervention, was performed at the New York Fringe Festival.[154]

Publications

Divine's manager and friend Bernard Jay wrote a book titled Not Simply Divine!, published in 1992 by Virgin Books. Admitting that he was "immensely proud" of Divine and the cause which he "strived for", Jay noted in the book's introduction that he wrote the work because he felt that Divine deserved a "memorial" that would act as a "record for posterity".[155] He insisted that Not Simply Divine! was "not the bitter revenge of an unappreciated manager, eager now to get his share of his praise", but that equally it was not "a gushing homage" designed to paint Divine as "both saintly and legendary."[155] He expressed his hope that the book shines light on the "shades of grey" between the man and his female persona, portraying a "warts and all" picture.[155] The book was criticized by Divine's mother, Frances Milstead, who accused Jay of writing a "mean-spirited" work that provided an incorrect image of her son.[156] Not Simply Divine! was also criticized by Divine's friend Greg Gorman, who remarked that, "there was so much hostility and so much meanspiritedness in the way Divine was portrayed in the book, that it was just 180 degrees from who he was."[157]

Frances Milstead subsequently cowrote her own book about Divine, entitled My Son Divine, with Kevin Heffernan and Steve Yeager, which was published by Alyson Books in 2001.[158] Postcards From Divine, a book composed of over 50 postcards Divine sent to his parents while traveling the world between 1977 and 1987, was released by the Divine estate on November 5, 2011.[159] Postcards From Divine also includes quotes and stories from his friends and colleagues, including Waters, Mink Stole, Mary Vivian Pearce, Channing Wilroy, Susan Lowe, Jean Hill, Tab Hunter, Lainie Kazan, Alan J. Wendl, Ruth Brown, Deborah Harry, Jerry Stiller, Ricki Lake, Silvio Gigante and others.[160]

Filmography

| Year | Film | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | Roman Candles | The Smoking Nun | |

| 1968 | Eat Your Makeup | Jacqueline Kennedy | |

| 1969 | The Diane Linkletter Story | Diane Linkletter | |

| Mondo Trasho | Divine | ||

| 1970 | Multiple Maniacs | Lady Divine | |

| 1972 | Pink Flamingos | Divine / Babs Johnson | |

| 1974 | Female Trouble | Dawn Davenport / Earl Peterson | |

| 1979 | Tally Brown, New York | Himself | Documentary |

| 1980 | The Alternative Miss World | Guest of Honour / Interviewer | Filmed in 1978 |

| 1981 | Polyester | Francine Fishpaw | |

| 1985 | Lust in the Dust | Rosie Velez | |

| Trouble in Mind | Hilly Blue | ||

| Divine Waters | Himself | Documentary | |

| 1987 | Tales from the Darkside | Chia Fung | 1 episode ("Seymourlama") |

| 1988 | Hairspray | Edna Turnblad / Arvin Hodgepile | Nominated – Independent Spirit Award for Best Supporting Male[161] |

| 1989 | Out of the Dark | Det. Langella | Released posthumously |

| 1998 | Divine Trash | Himself | Archive footage used for documentary |

| 2000 | In Bad Taste | ||

| 2002 | The Cockettes | ||

| 2013 | I Am Divine |

Discography

Albums

| Year | Title | Record company |

|---|---|---|

| 1982 | Jungle Jezebel (AKA My First Album) | O Records[162] / Metronome[163] |

| 1984 | T Shirts and Tight Blue Jeans (Non Stop Dance Remix) | Break Records[164] |

Compilation albums

| Year | Title | Record company |

|---|---|---|

| 1984 | The Story So Far | Bellaphon[165] |

| 1988 | Maid in England | Bellaphon[166] |

CD reissues

| Year | Title | Record company |

|---|---|---|

| 1988 | The Story So Far | Receiver Records, KNOB 3 |

| 1989 | The Best of & The Rest Of | Action Replay Records, CDAR 1007 |

| 1990 | Maid in England | ZYX Records, CD 9066 |

| 1991 | The Best of Divine: Native Love | "O" Records, HTCD 16-2 |

| 1993 | The 12" Collection | Unidisc Music Inc., SPLK-7098 |

| 1994 | Jungle Jezebel | "O" Records, HTCD 6609 |

| 1994 | The Cream of Divine | Pickwick Group Ltd., PWKS 4228 |

| 1994 | Born to Be Cheap | Anagram Records, CDMGRAM 84 |

| 1995 | Shoot Your Shot | Mastertone Multimedia Ltd., AB 3013 |

| 1996 | The Remixes | Avex UK, AVEXCD 29 |

| 1996 | The Originals | Avex UK, AVEXCD 30 |

| 1997 | The Best of Divine | Delta Music, 21 024 |

| 2005 | Greatest Hits | Unidisc Music Inc., SPLK-8004 |

| 2005 | The Greatest Hits | Forever Gold, FG351 |

| 2009 | Greatest Hits: The Originals and the Remixes | Dance Street Records, DST 77226-2 |

| 2011 | Essential Divine | Right Trackt Records |

Singles

| Year | Title | Peak chart positions | Album | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUS [167] |

AUT [168] |

GER [169] |

NLD [170] |

NZ [171] |

SWI [172] |

UK [173] |

US Dance [174] | |||

| 1981 | "Born to Be Cheap" / "The Name Game" | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Non-album single. B-side also known as "Gang Bang." |

| 1982 | "Native Love (Step by Step)" / "Alphabet Rap" | — | — | — | 28 | — | — | — | 21 | Jungle Jezebel / My First Album |

| "Shoot Your Shot" / "Jungle Jezebel" | — | 9 | 15 | 7 | — | 8 | — | 39 | ||

| 1983 | "Love Reaction" | — | — | 55 | 25 | — | — | 65 | — | The Story So Far |

| "Shake It Up" | — | — | 26 | 13 | — | — | 82 | — | ||

| 1984 | "You Think You're a Man" / "Give It Up" | 8 | — | 32 | — | 27 | 9 | 16 | — | |

| "I'm So Beautiful" / "Show Me Around" | — | — | 38 | — | 48 | — | 52 | — | ||

| "T Shirts and Tight Blue Jeans" | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Non-album single | |

| 1985 | "Walk Like a Man" | 75 | — | 52 | — | — | 28 | 23 | — | Maid in England |

| "Twistin' the Night Away" | — | — | — | — | — | — | 47 | — | ||

| "Hard Magic" | — | — | — | — | — | — | 87 | — | ||

| 1987 | "Little Baby" | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| "Hey You!" | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1989 | "Shout It Out" | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Posthumous non-album single. Recorded in 1983. |

- Besides aforementioned singles, Divine also recorded such songs as "Female Trouble", "Kick Your Butt" and "Psychedelic Shack", making a total of 22 different tracks.

References

Footnotes

- Darrach 1988.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 28.

- Jay 1993, p. 13.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 7–8.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 7.

- Kaltenbach 2009.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 8–9.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 9.

- Jay 1993, p. 14.

- Jay 1993, pp. 14–15.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 10.

- Jay 1993, p. 15.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 27.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 24.

- Jay 1993, p. 17.

- Jay 1993, pp. 18–19.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 4.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 35, 40.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 2, 35, 44.

- Waters 2005, pp. 47, 52.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 35.

- Waters 2005, p. 148.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 45.

- Waters 2005, pp. 41–42, 150.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 46.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 1.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 45–46.

- Jay 1993, pp. 23–24.

- Waters 2005, p. 49.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 47.

- Jay 1993, p. 25.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 47–48.

- Jay 1993, p. 21.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 59.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 49.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 50.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 56–57.

- Jay 1993, pp. 26–27.

- Waters 2005, p. 54.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 51–52.

- Waters 2005, p. 61.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 53–54.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 55.

- Waters 2005, p. 67.

- Jay 1993, pp. 28–31.

- Jay 1993, pp. 27–28.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 57.

- Waters 2005, pp. 62–64.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 57–59.

- Waters 2005, p. 2.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 61.

- Waters 2005, p. 7.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 61–65.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 65.

- Waters 2005, pp. 12–14.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 66–67.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 69–70.

- Waters 2005, p. 21.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 70–71.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 2, 68–69.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 67–68.

- Jay 1993, p. 33.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 78.

- Waters 2005, pp. 72–74.

- Gamson 2005, pp. 241–242.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 85.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 79.

- Waters 2005, p. 151.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 85–86.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 74–76.

- Waters 2005, p. 95.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 77–78.

- Waters 2005, p. 100.

- Jay 1993, p. 35.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 77.

- Waters 2005, p. 108.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 84.

- Levy, Joseph. "A Brief History of Rough Trade". Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- Jay 1993, pp. 34–41.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 89, 91–92.

- Waters 2005, pp. 145, 160.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 91.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 97–99.

- Jay 1993, p. 43.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 92–95.

- Waters 2005, p. 145.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 96–97.

- Jay 1993, pp. 70–75.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 97.

- Jay 1993, pp. 93–100.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 102.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 103.

- Jay 1993, p. 110.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 2, 5, 107–108.

- Jay 1993, pp. 143–145.

- Jay 1993, pp. 113–123.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 113.

- Jay 1993, pp. 129, 136, 172 and 182.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 118.

- Jay 1993, pp. 150–154, 178.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 113–115, 128.

- O'Grady 2012, pp. 276–283.

- Jay 1993, pp. 164–165.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 119–121.

- Jay 1993, pp. 179–181.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 122–125.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 137.

- Rubenstein 1988.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 135.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 140.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 141–145.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 150.

- Jay 1993, pp. 137–139.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 149.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 113–115, 153.

- Jay 1993, p. 224.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 154–155.

- Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 12421-12422). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- Jay 1993, pp. 225–226.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 155–162.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 163.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 164.

- Jay 1993, p. 105.

- Jay 1993, p. 171.

- Jay 1993, p. 151.

- Jay 1993, p. 90.

- Jay 1993, p. 184.

- Jay 1993, pp. 199–200.

- Jay 1993, pp. 216–217.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 114.

- Jay 1993, p. 128.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 38.

- Jay 1993, p. 3.

- Jay 1993, pp. 126, 56.

- Waters 2005, p. 154.

- Jay 1993, pp. 101–104.

- Jay 1993, p. 203.

- Jay 1993, pp. 197–198.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 117.

- Jay 1993, p. 199.

- Jay 1993, p. 200.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. preface.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 86.

- Jay 1993. pp. 146–147.

- Jay 1993, p. 57.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, pp. 112, 149–150.

- Jay 1993, p. 206.

- ""Divine" biography". The New York Times. Retrieved December 5, 2007.

- Thornquist, Paul (March 1988). Letter to The New York Post.

- Hegarty, Antony, 1998. Track 9. "Divine". Antony and the Johnsons, Secretly Canadian.

- "Movie Star". Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- Willman, Chris (July 31, 2012). "Entertainment Weekly: DVD Review The Little Mermaid". Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- "American Visionary Art Museum". Avam.org. October 6, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- "Divine intervention: A final night with a drag legend". BBC News. August 20, 2015.

- Jay 1993, pp. ix–xi.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 108.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001, p. 124.

- Milstead, Heffernan & Yeager 2001.

- Brodie, Noah, ed. (2011). Postcards From Divine. ISBN 978-0615537061.

- "Postcards From Divine". Facebook. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- "Awards for Hairspray". IMDB.

- "Divine – Jungle Jezebel at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- "Divine – My First Album at Discogs". Discogs.com. November 7, 2004. Archived from the original on January 30, 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- "Divine - T Shirts and Tight Blue Jeans (Non Stop Dance Remix)".

- "Divine – The Story So Far". Discogs.com. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- "Divine – Maid In England (CD, Album) at Discogs". Discogs.com. March 5, 2010. Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 91. ISBN 0-646-11917-6. N.B. The Kent Report chart was licensed by ARIA between mid-1983 and 19 June 1988.

- "Divine – Discography". austriancharts.at. Austrian Charts Online. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- "Offizielle Deutsche Charts: "Divine" (singles)". GfK Entertainment. Archived from the original on November 2, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- "Divine – Discography". dutchcharts.nl. Dutch Charts Online. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- "Divine – Discography". charts.org.nz. New Zealand Charts Online. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- "Divine – Discography". hitparade.ch. Swiss Charts Online. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- "Official Charts > Divine". The Official UK Charts Company. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- Divine – Billboard Singles AllMusic. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

Bibliography

- Curley, Mallory (2010). A Cookie Mueller Encyclopedia. Randy Press.

- Darrach, Brad (March 21, 1988). "Death Comes to a Quiet Man Who Made Drag Queen History as Divine". People. 29 (11).

- Fallowell, Duncan (October 27, 1994). "Divine". 20th Century Characters. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-009947041-0.

- Gamson, Joshua (2005). The Fabulous Sylvester: The Legend, the Music, the 70s in San Francisco. New York City: Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 978-0-8050-7250-1.

- Jay, Bernard (1993). Not Simply Divine!. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-86369-740-1.

- Kaltenbach, Chris (March 24, 2009). "Frances Milstead, mother of Divine, dies at 88". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- Milstead, Frances; Heffernan, Kevin; Yeager, Steve (2001). My Son Divine. Los Angeles and New York: Alyson Books. ISBN 978-1-55583-594-1.

- O'Grady, Paul (2012). Still Standing: The Savage Years. London: Bantam. ISBN 978-0-593-06939-4.

- Rubenstein, Hal (February 1988). "Interview with Divine". Interview. New York City: Brant Publications. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- Waters, John (2005) [1981]. Shock Value: A Tasteful Book about Bad Taste. Philadelphia: Running Press. ISBN 978-1-56025-698-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Divine. |