December 1964 South Vietnamese coup

The December 1964 South Vietnamese coup took place before dawn on December 19, 1964, when the ruling military junta of South Vietnam led by General Nguyễn Khánh dissolved the High National Council (HNC) and arrested some of its members. The HNC was an unelected legislative-style civilian advisory body they had created at the request of the United States—South Vietnam's main sponsor—to give a veneer of civilian rule. The dissolution dismayed the Americans, particularly the ambassador, Maxwell D. Taylor, who engaged in an angry war of words with various generals including Khánh and threatened aid cuts. They were unable to do anything about the fait accompli that had been handed to them, because they strongly desired to win the Vietnam War and needed to support the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. Instead, Taylor's searing verbal attacks were counterproductive as they galvanized the Vietnamese officers around the embattled Khánh. At the time, Khánh's leadership was under threat from his fellow generals, as well as Taylor, who had fallen out with him and was seeking his removal.

| December 1964 South Vietnamese coup | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

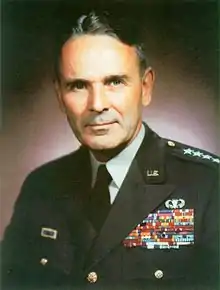

Nguyễn Khánh, the leader of the coup, in 1964 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

other civilian politicians | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Nguyễn Khánh Nguyễn Chánh Thi Nguyễn Cao Kỳ |

Dương Văn Minh Phan Khắc Sửu | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown small number | None | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | |||||||

The genesis of the removal of the HNC was a power struggle within the ruling junta. Khánh, who had been saved from an earlier coup attempt in September 1964 by the intervention of some younger generals dubbed the Young Turks, was indebted to them and needed to satisfy their wishes to stay in power. The Young Turks disliked a group of older officers who had been in high leadership positions but were now in powerless posts, and wanted to sideline them completely. As a result, they decided to hide their political motives by introducing a policy to compulsorily retire all general officers with more than 25 years of service. The chief of state Phan Khắc Sửu, an elderly figure appointed by the military to give a semblance of civilian rule, did not want to sign the decree without the agreement of the HNC, which mostly consisted of old men. The HNC recommended against the new policy, and the younger officers, led by I Corps commander General Nguyễn Chánh Thi and Air Marshal Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, disbanded the body and arrested some of its members along with other politicians.

As a result of this event, Taylor summoned Khánh to his office. Khánh sent Thi, Kỳ, the commander of the Republic of Vietnam Navy Admiral Chung Tấn Cang and IV Corps commander General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, and after beginning with "Do all of you understand English?",[1][2][3] Taylor harshly berated them and threatened cuts in aid. While angered by Taylor's manner, the officers defended themselves in a restrained way. The next day Khánh met Taylor and the Vietnamese leader made oblique accusations that the U.S. wanted a puppet ally; he also criticized Taylor for his manner the previous day. When Taylor told Khánh he had lost confidence in his leadership, Taylor was threatened with expulsion, to which he responded with threats of total aid cuts. Later however, Khánh said he would leave Vietnam along with some other generals he named, and during a phone conversation, asked Taylor to help with travel arrangements. He then asked Taylor to repeat the names of the would-be exiles for confirmation, and Taylor complied, not knowing that Khánh was taping the dialogue. Khánh then showed the tape to his colleagues out of context, misleading them into thinking that Taylor wanted them expelled from their own country to raise the prestige of his embattled leadership.

Over the next few days, Khánh embarked on a media offensive, repeatedly criticizing U.S. policy and decrying what he saw as an undue influence and infringement on Vietnamese sovereignty, explicitly condemning Taylor and declaring the nation's independence from "foreign manipulation".[3][4][5] Khánh and the Young Turks began preparations to expel Taylor before changing their minds; however, Khánh's misleading tactics had rallied the Young Turks around his fragile leadership for at least the short-term future. The Americans were forced to back down on their insistence that the HNC be restored and did not carry through on Taylor's threats to cut off aid, despite Saigon's defiance.

Background

On September 26, 1964, Nguyễn Khánh and the senior officers in his military junta created a semblance of civilian rule by forming the High National Council (HNC), an appointed advisory body akin to a legislature. This came after lobbying by American officials—led by Ambassador Maxwell Taylor—in Vietnam,[6][7] as they placed great value in the appearance of civilian legitimacy, which they saw as vital to building a popular base for any government. Khánh put his rival General Dương Văn Minh—who he had deposed in a January 1964 coup—in charge of picking the 17 members of the HNC, and Minh filled it with figures sympathetic to him. The HNC then made a resolution to recommend a political model with a powerful head of state, which would likely be Minh, given their sympathy towards him. Khánh did not want his rival taking power, so he and the Americans convinced the HNC to dilute the powers of the position to make it unappealing to Minh, who was then sent on an overseas diplomatic goodwill tour to remove him from the political scene. However, Minh was back in South Vietnam after a few months and the power balance in the junta was still fragile.[6]

The HNC, which had representatives from a wide range of social groups, selected the aging civilian politician Phan Khắc Sửu as chief of state, and Suu chose Trần Văn Hương as prime minister, a position that had greater power. However, Khánh and the senior generals retained the real power.[7][8] At the same time, a group of Catholic officers were trying to replace Khánh with their co-religionist, General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, and the incumbent was under pressure.[9] During 1964, South Vietnam had suffered a succession of setbacks on the battlefield, in part due to disunity in the military and a focus on coup plotting.[10][11] In the meantime, both Saigon and Washington were planning a large-scale bombing campaign against North Vietnam in an attempt to deter communist aggression, but were waiting for stability in the south before starting the air strikes.[12]

Compulsory retirement policy

Khánh and a group of younger officers called the Young Turks—led by chief of the Republic of Vietnam Air Force, Air Marshal Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, commander of I Corps General Nguyễn Chánh Thi and IV Corps commander Thiệu—wanted to forcibly retire officers with more than 25 years of service, as they thought them to be lethargic and ineffective, but most importantly, rivals for power.[13] Most of the older officers had more experience under the Vietnamese National Army during the French colonial era, and some of the younger men saw them as too detached from the modern situation.[2] The Young Turks had quite a lot of influence over Khánh, as Thi and Kỳ had intervened militarily to save him from a coup attempt in September by Generals Lâm Văn Phát and Dương Văn Đức.[14]

One of the specific and unspoken aims of this proposed policy was to remove Generals Minh, Trần Văn Đôn, Lê Văn Kim and Mai Hữu Xuân from the military. This quartet, along with Tôn Thất Đính, had been the leading members of a junta that overthrew President Ngô Đình Diệm in November 1963.[15] The generals who deposed Diệm did not trust Khánh because of his habit of changing sides, and Khánh was angered by their snubs. Khánh put Don, Kim, Xuan and Dinh under arrest in Da Lat after his January coup,[16] claiming they were about to make a deal with the communists, a falsehood to cover up his motive of revenge.[16] These four thus became known as the "Da Lat Generals". Khánh later released them and placed them into meaningless desk jobs with no work to do, although they were still being paid.[17] Khánh did this as he thought the Young Turks had become too powerful and he hoped to use the Da Lat Generals as a counterweight. All this time, Minh had been allowed to continue as a figurehead chief of state due to his popularity, but Khánh was intent on sidelining him too.[17] The Young Turks were fully aware of Khánh's motives for rehabilitating the Da Lat Generals, and wanted to marginalize them.[18] In public, Khánh and the Young Turks claimed the Da Lat Generals and Minh, who had returned from his overseas tour, had been making plots with the Buddhist activists to regain power.[1][19]

Suu's signature was required to pass the ruling, but he referred the matter to the HNC to get their opinion.[19] The HNC turned down the request. There was speculation the HNC did this as many of them were old, and therefore did not appreciate the generals' negativity towards seniors—some South Vietnamese mockingly called the HNC the High National Museum.[2] On December 19, a Saturday, the generals moved to dissolve the HNC by arresting some of its members.[13] The HNC had already ceased to function in any meaningful way, as only 9 of the 17 members were still occasionally attending its meetings, and few on a regular basis.[17]

Dissolution of the High National Council

Before dawn on December 19, there were troop movements in the capital as the junta deposed the civilians. The operation was commanded by Thi—who had travelled into Saigon from I Corps in the far north—and Kỳ. The national police, which was under the control of the army, moved through the streets, arresting five HNC members, other politicians and student leaders they deemed to be an obstacle to their aims.[17][19] Minh and the other aging generals were arrested and flown to Pleiku, a Central Highlands town in a Montagnard area, while other officers were simply imprisoned in Saigon.[1] The junta's forces also arrested around 100 members of the National Salvation Council (NSC) of Le Khac Quyen; the NSC was a new party active in central Vietnam in the I Corps region and opposed to the expansion of the war. It was aligned with Thi and the Buddhist activist monk Thích Trí Quang, but as Thi was active in the purge, it was believed he had fallen out with Quyen.[20]

At this point, Khánh had not spoken up and allowed the impression that the moves had been made without his consultation or against his will, and an attempt on the part of other officers to take power themselves.[19] Hương had actually privately endorsed the dissolution of the HNC, as both he and the Young Turks thought it would allow them to gain more power and influence over Khánh.[21]

The infighting exasperated Taylor, the US Ambassador to South Vietnam and former Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff,[3] who felt the disputes between the junta's senior officers were derailing the war effort.[22][23] Only a few days earlier, General William Westmoreland—the commander of US forces in Vietnam—had invited him and the Vietnamese generals home to a dinner. There Taylor asked for an end to the persistent changes in leadership, and Khánh and his men assured him of stability.[2] Westmoreland warned that persistent instability would turn the American political class and public against Saigon, as they would deem it useless to support such a regime.[1] Taylor initially cabled the State Department back in the US to state a "naked military fist" had "crumpled [the] carefully woven fabric of civilian government",[24] and that the arrest of the civilians would be "immediately and understandably interpreted by all the world as another military coup, setting back all that had been accomplished" since the formation of the HNC and the creation of a veneer of civilian rule.[24] He went on to say that an "inescapable conclusion that if a group of military officers could issue decisions abolishing one of the three fundamental organs of the governmental structure ... and carry out military arrests of civilians, that group of military officers has clearly set themselves above and beyond the structure of government in Vietnam."[24] Taylor bemoaned the fact that the generals had shown no second thoughts about ignoring US policy recommendations, particularly in disregarding his explicit advice to maintain stable civilian rule, at least at a nominal level.[24] Taylor issued a thinly disguised threat to cut aid, releasing a public statement saying Washington might reconsider its military funding if "the fabric of legal government" was not reinstated.[20]

Angry confrontations with Maxwell Taylor

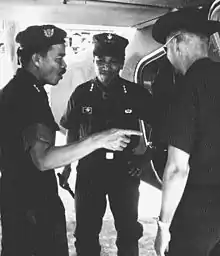

Taylor summoned Khánh to his office, but the Vietnamese leader sent Thi, Kỳ, Thiệu and Admiral Chung Tấn Cang, the commander of the Republic of Vietnam Navy, instead.[19] Taylor asked the four to sit down and then said "Do all of you understand English?"[1][2][3] The ambassador then angrily denounced the officers. According to Stanley Karnow, Taylor "launched into a tirade, scolding them as if he were still superintendent of West Point and they a group of cadets caught cheating".[1] He said "I told you all clearly at General Westmoreland's dinner we Americans were tired of coups. Apparently I wasted my words."[2] He decried the removal of the HNC as "totally illegal", and said it had "destroyed the government-making process",[24] and that "I made it clear that all the military plans I know you would like to carry out are dependent on government stability",[25] something he felt had been lost with the dismissal of the HNC.[25] He said "... you have made a real mess. We cannot carry you forever if you do things like this."[2] Taylor believed the HNC to be an essential part of the government, because as an American, he believed civilian legitimacy was a must.[2] For him, the HNC was a necessary step in a progression towards an elected civilian legislature, which he regarded as critical for national and military morale.[2] The historian Mark Moyar regarded Taylor's intervention as unnecessary, and noted that there had been many instances of fierce fighting in Vietnamese history despite the complete absence of democracy throughout the nation's history.[2] Taylor also reminded them of an earlier meeting where he had discussed an American plan to expand the war, increase funding for the South Vietnamese military, and to go on the offensive against the communists at the request of Khánh. Taylor said the Americans would not be able to help Saigon pursue their desired military strategy if the political machinations did not stop.[24] Taylor said that if the military did not transfer some powers or advisory capacity back to the HNC or another civilian institution, aid would be withheld, and some planned military operations against the Ho Chi Minh trail—which was being used to infiltrate communists into the south—would be suspended.[19]

The four officers were taken aback by Taylor's searing words and felt they had been humiliated. A decade after the incident, Kỳ described Taylor as "the sort of man who addressed people rather than talked to them", referencing the confrontation.[22] Karnow said "For the sake of their own pride, they [the Vietnamese officers] resented being treated in ways that reminded them of their almost total dependence on an alien power. How could they preserve a sense of sovereignty when Taylor, striving to push them into 'getting things done', behaved like a viceroy?"[22] However, Thi also took a perverse pleasure in riling Taylor. He was seen by a CIA officer soon after, grinning. When asked why he was happy, Thi said "Because this is one of the happiest days of my life ... Today I told the American ambassador that he could not dictate to us."[26] Nevertheless, Taylor's conduct had rankled the officers, stirring their latent sense of nationalism and anti-Americanism; Khánh would exploit this to strengthen his fragile position in the junta.[27]

Khánh's quartet of delegates responded to Taylor in a circumlocutory way. They remained calm and did not resort to direct confrontation. Kỳ said the change was necessary, as "the political situation is worse than it ever was under Diệm".[21] Kỳ explained that the situation mandated the dissolution of the council, saying "We know you want stability, but you cannot have stability until you have Unity."[21] He claimed some HNC members were disseminating coup rumors and creating doubt among the population, and that "both military and civilian leaders regard the presence of these people in the High National Council as divisive of the Armed Forces due to their influence".[21] Kỳ further accused some of the HNC members of being communist sympathizers and cowards who wanted to stop the military from strengthening.[25] He promised to explain the decision at a media conference and vowed that he and his colleagues would return to purely military roles in the near future.[28] Thiệu added "I do not see how our action has hurt the Hương government ... Hương now has the full support of the Army and has no worries from the High National Council, which we have eliminated."[28] Cang said "It seems ... we are being treated as though we were guilty. What we did was only for the good of the country."[25]

When Taylor said the moves detracted from Hương and Suu's powers, the officers disagreed and said they supported the pair in full and that Hương had approved of the HNC's dissolution. Taylor was unimpressed by the reassurances, concluding with "I don't know whether we will continue to support you after this ... You people have broken a lot of dishes and now we have to see how we can straighten out this mess."[28] Taylor's deputy, U. Alexis Johnson felt the discussion had become counterproductive and was increasing the problem. He suggested that should the generals feel unwilling to alter their position immediately, they should refrain from actions that would preclude a later change of heart.[25] He proposed they merely announce the removal of certain members of the HNC rather than the dissolution of the entire body, hoping the HNC could be reconstituted with figures they deemed to be more satisfactory.[25] The four officers did not give a clear answer to Johnson's idea, indicating they had not made a concrete decision by saying "the door is not closed".[25]

Taylor meets Hương

When Taylor met Hương afterwards, he urged the prime minister to reject the dissolution of the HNC. Hương said he and Suu had not been notified of the moves, but agreed to step in and take over the body's work. Taylor nevertheless asked Hương to publicly condemn the coup and call on the army to release those arrested.[28] Hương also said he would be willing to reorganize his administration to meet the wishes of the military,[20] and that retaining their support was essential in keeping a civilian government functional.[29] Taylor said the US did not agree with military rule as a principle, and might reduce aid, but Hương was unmoved and said the Vietnamese people "take a more sentimental than legalistic approach" and that the existence of civilian procedure and the HNC was much less pressing than the "moral prestige of the leaders".[28] American military advisers and intelligence officers who liaised with senior junta members found they were unconcerned with any possible legal ramifications of their actions.[21]

Later, despite Taylor's pleas to keep the dissolution of the HNC secret in the hope it would be reversed,[24] Kỳ, Thi, Thiệu and Cang called a media conference, where they maintained the HNC had been dissolved in the nation's best interests. The quartet vowed to stand firm and not renege on their decision. They also proclaimed their ongoing confidence for Suu and Hương.[19] Two days later, Khánh went public in support of the Young Turks' coup against the HNC, condemning the advisory body and asserting the army's right to intervene if "disputes and differences create a situation favorable to the common enemies: Communism and colonialism".[19] The generals announced they had formed a new body called the Armed Forces Council (AFC) to succeed the current Military Revolutionary Council,[20] and referred to the dissolution of the HNC as Decision No. 1 of the AFC.[27] The American policymakers viewed the public moves by the Vietnamese generals as "throwing down the gauntlet" and challenging their counsel.[27]

Taylor meets Khánh

The day after the Young Turks' press conference, Taylor privately met Khánh at the latter's office. He complained about the dissolution of the HNC and said it did not accord with the values of the alliance and the loyalty Washington expected of Saigon.[22][23][30] He added that the US could not cooperate with two governments at once: a military regime that held power while a civilian body took the responsibility.[25] Khánh testily replied that Vietnam was not a satellite of the US and compared the situation to the US support of the successful coup against Diệm, saying that loyalty was meant to be reciprocated. Khánh had hinted that he felt the Americans were about to have him deposed like Diệm, who was then assassinated, but this rankled Taylor, who had argued against the regime change.[31] Taylor then bemoaned Khánh, saying he had lost confidence in the Vietnamese officer,[22][23][30] recommending Khánh resign and go into exile.[27] He also said military supplies currently being shipped to Vietnam would be withheld after arriving in Saigon and that American help in planning and advising military operations would be suspended.[32]

Khánh bristled and said "You should keep to your place as Ambassador ... as Ambassador, it is really not appropriate for you to be dealing in this way with the commander-in-chief of the armed forces on a political matter, nor was it appropriate for you to have summoned some of my generals to the Embassy yesterday."[33] He threatened to expel Taylor, who responded by saying a forced departure would mean the end of US support.[22] However, Khánh later said he was open to the possibility of going abroad and asked Taylor if he thought this would be good for the country, to which the ambassador replied in the affirmative.[33] Khánh also said he took responsibility for his generals' actions, and expressed regret at what they had done.[25] Khánh then ended the meeting, saying he would think about his future.[33]

Later, Khánh phoned Taylor from his office and expressed his desire to resign and go abroad along with several other generals, asking for the Americans to fund the travel costs. He then read Taylor the list of generals for whom arrangements needed to be made, and asked the ambassador to repeat the names for confirmation. Taylor did so, unaware Khánh was taping the dialogue.[33] Afterwards, Khánh played the tape out of context to his colleagues, giving them the impression Taylor was calling for their expulsion from their own country.[27][33] Khánh then asked his colleagues to participate in a campaign of fomenting anti-American street protests and to give the impression the country did not need Washington's aid.[34] A CIA informant reported the recent arguments with Taylor had incensed the volatile Thi so much that he had privately vowed to "blow up everything" and "kill Phan Khắc Sửu, Trần Văn Hương and Nguyễn Khánh and put an end to all this. Then we will see what happens."[27]

Public media campaign by Khánh

On the morning of December 22, as part of his Order of the Day,[35] a regular message to the armed forces over Radio Vietnam, Khánh went back on his promise to leave the country and announced, "We make sacrifices for the country's independence and the Vietnamese people's liberty, but not to carry out the policy of any foreign country."[23][29][33] He said it was "better to live poor but proud as free citizens of an independent country rather than in ease and shame as slaves of the foreigners and Communists."[36] Khánh pledged support for both Hương and Suu's civilian rule,[29] and condemned colonialism in a thinly veiled reference to the US.[35]

Khánh explicitly denounced Taylor in an exclusive interview with Beverly Deepe[35] published in the New York Herald Tribune on December 23,[22][33] saying "if Taylor did not act more intelligently, Southeast Asia would be lost" and that the US could not expect to succeed by modelling South Vietnam on American norms.[36] Khánh said Taylor and the US would need to be "more practical and not have a dream of having Vietnam be an image of the United States, because the way of life and people are entirely different."[33] He added that Taylor's "attitude during the last 48 hours—as far as my small head is concerned—has been beyond imagination".[19] Justifying the removal of the HNC, Khánh said they were "exploited by counter-revolutionary elements who placed partisan considerations above the homeland's sacred interest."[34] Khánh also threatened to divulge the content of his discussion with Taylor, saying "One day I hope to tell the Vietnamese people and the American people about this ... It is a pity because Gen. Taylor is not serving his country well."[37]

Khánh had not divulged that angry discussions had occurred in private, so Deepe was unsure what had happened between Taylor and Khánh to provoke such an outburst. She contacted the US Embassy to ask what the dispute was about. At first, the Americans defended Taylor without referring to what the problem was, stating: "Ambassador Taylor has undertaken no activities which can be considered improper in any way ... All his activities are designed to serve the best interests of both Vietnam and the United States."[37] The State Department issued a statement later in the day in more robust terms, saying "Ambassador Taylor has been acting throughout with the full support of the U.S. government ... a duly constituted government exercising full power ... without improper interference ... is the essential condition for the successful prosecution of the effort to defeat the Viet Cong."[37] The following day, Secretary of State Dean Rusk said aid would have to be cut, as the programs being funded needed an effective government to be useful.[37] Taylor later responded by calling the generals' actions an "improper interference" into the purview of civilian government.[34]

Defying Taylor earned Khánh heightened approval among his junta colleagues, as the ambassador's actions were seen as an insult to the nation.[33] On the night of December 23, Khánh convinced his fellow officers to join him in lobbying Hương to declare Taylor persona non grata and expel him from South Vietnam. They were confident Hương could not reject them and side with a foreign power at the expense of the military that had installed him, and made preparations to meet him the next day.[33] Khánh also told Hương that if Taylor was not ejected, he and the other generals would hold a media conference and release "detailed accounts" of the ambassador's confrontation with the quartet and his "ultimatum to General Khánh" the day after.[29] However, someone in the junta was a CIA informant and reported the incident, allowing American officials to individually lobby the officers to change their stance.[33] At the same time, the Americans informed Hương if Taylor was expelled, US funding would stop.[29] The next day, the generals changed their mind and when they met Hương at his office, only asked him to formally denounce Taylor's behavior in his meetings with Khánh and his quartet and to "take appropriate measures to preserve the honor of all the Vietnamese armed forces and to keep national prestige intact".[38]

On December 24, Khánh issued a declaration of independence from "foreign manipulation",[23] and condemned "colonialism",[22] explicitly accusing Taylor of abusing his power.[29] At the time, Khánh was also secretly negotiating with the communists, hoping to put together a peace deal so he could expel the Americans from Vietnam, although this effort did not lead anywhere in the two months before he was forced out of power.[39] For his part, Taylor privately told Americans journalists that Khánh was expressing opposition to the US merely because he knew he had lost Washington's confidence. Taylor said Khánh was completely unprincipled and was stirring up anti-American sentiment purely to try to shore up his political prospects, not because he thought US policy was harmful to South Vietnam.[29] The US media were generally very critical of Khánh's actions and did not blame Taylor for the disharmony.[37] Peter Grose of The New York Times said "It almost seems as if Viet Cong insurgents and the Saigon government conspired to make the United States feel unwelcome."[37] The Chicago Tribune lampooned Khánh's junta, calling it a "parody of a government" and saying it would not survive for a week without US support and describing the generals as "remittance men on the United States' payroll".[37] However, the New York Herald Tribune said it was dangerous to pressure South Vietnam too much, citing the instability that followed the American support for the coup against Diệm, who had resisted US advice so often. It said "The issue is not General Khánh versus General Taylor. It is whether the Vietnamese still have the will to exist as an independent state."[40] The newspaper said if the answer was yes, then both Washington and Saigon would have to look beyond personalities.[40]

Angry with Deepe for airing Khánh's grievances against him, Taylor invited every other US journalist in Saigon to this private briefing. Taylor gave the journalists his account of the dispute and discussions with the generals, and hoped it would be useful background information for the media, so they would understand what he had done and not reach negative conclusions about his conduct in their writing.[40] Due to the sensitivity of the situation, he asked them to keep the remarks off the record.[41] However, someone at the briefing informed Deepe of what Taylor had said, and she published the remarks on December 25 under the title "Taylor Rips Mask Off Khánh".[41] In this article, comments were also attributed to Taylor describing some South Vietnamese officers as borderline "nuts" and accusing many generals of staying in Saigon and allowing their junior officers to run the war as they saw fit.[41] Deepe's article caused an uproar due to the tension between Taylor and the Vietnamese generals.[41]

Brinks Hotel bombing

At the same time, Westmoreland became concerned with the growing antipathy towards the US and requested the United States Pacific Command (CINCPAC): "In view of the current unstable political situation ... and the possibility that this situation could lead to anti-American activities of the unknown intensity, request Marine Landing Force now off Cap Varella be positioned out of sight of land off Cap St. Jacques soonest."[29] Better known as Vũng Tàu, Cap St. Jacques was a coastal city at the mouth of the Saigon River around 80 km southeast of the capital. Westmoreland also put American marines based at Subic Bay in the Philippines on notice.[29]

On the same day, the Viet Cong bombed the Brinks Hotel, where US officers were billeted, killing two Americans and injuring around 50 people, civilian bystanders and military personnel. As a result, there was a suspicion among a minority that Khánh's junta had been behind the attack,[3] even though the Viet Cong had claimed responsibility through a radio broadcast. When the Americans started making plans to retaliate against North Vietnam, they did not tell Khánh and his junta.[42] Westmoreland, Taylor, and other senior US officers in Saigon and Washington urged President Lyndon Baines Johnson to authorize reprisal bombings against North Vietnam,[3][42] Taylor predicting: "Some of our local squabbles will probably disappear in enthusiasm which our action would generate."[3] Johnson refused and one reason was the political instability in Saigon. Johnson reasoned the international community and the American public were unlikely to believe the Viet Cong were behind the attack, feeling they would instead blame local infighting for the violence.[43] Johnson administration officials did not conclude that the communists were responsible until four days after the attack.[42][43] The State Department cabled Taylor, saying "In view of the overall confusion in Saigon", public US and international opinion towards an American air strike would be that the Johnson administration was "trying to shoot its way out of an internal [South Vietnamese] political crisis".[43]

Fall out

As a result of the tension in late-December, the standoff remained. The US hoped the generals would relent because they could not survive and be able to repel the communists or rival officers without aid from Washington. On the other hand, Khánh and the Young Turks expected the Americans would become more worried about the communist gains first and acquiesce to their fait accompli against the HNC.[19] The generals were correct.[38]

The South Vietnamese eventually had their way. As the generals and Hương were unwilling to reinstate the HNC, Taylor sent General John L. Throckmorton to meet them and mend relations. Throckmorton told the Vietnamese generals they had read too much into Taylor's comments and that the US had no intention of pressuring them out of power with aid cuts.[38] Cang appeared unimpressed, while Thiệu and Kỳ made indirect and vague comments about what they perceived to be misleading tactics during the talks.[41] Khánh appeared reassured by Throckmorton's overtures and made a public statement on December 30, saying he was not as hostile to the Americans as reported, and he wanted Thiệu and Cang to meet the Americans to relieve any remaining tension.[38] He also claimed privately that the statements attributed to him by Deepe were false and set up a bilateral committee to discuss tensions.[44] The generals eventually won out, as the Americans did not move against them in any way for their refusal to reinstate the HNC.[19] The South Vietnamese won in large part because the Americans had spent so much on the country, and could not afford to abandon it and lose to the communists over the matter of military rule, as a communist takeover would be a big public relations coup for the Soviet bloc. According to Karnow, for Khánh and his officers, "their weakness was their strength".[22] An anonymous South Vietnamese government official said "Our big advantage over the Americans is that they want to win the war more than we do."[22]

The only concession the AFC made was on January 6, 1965, when they made a charade move of officially renouncing all their power to Hương, who was asked to organize elections.[45] They also agreed to appoint a civilian body and release those arrested in December.[32] Khánh had proposed to reinstate civilian rule if a military "organ of control" was created to keep control of them, but Taylor quashed the idea.[44] This resulted in an official announcement by Hương and Khánh three days later, in which the military again reiterated their commitment to civilian rule through an elected legislature and a new constitution, and that "all genuine patriots" would be "earnestly assembled" to collaborate in making a plan to defeat the communists.[32] The Americans were not impressed with the statement, which was shown to Taylor before it was made public; the State Department dourly announced that "it appears to represent some improvement to the situation".[46] Nevertheless, Khánh and Taylor were both signatories to this January 9 announcement.[44]

Although the coup was a political success for Khánh, it was not enough to stabilize his leadership in the long run. During the dispute over the HNC, Khánh had tried to frame the dispute in nationalistic terms against what he saw as overbearing US influence.[47] In the long run, this failed, as South Vietnam and the senior officers' careers and advancement were dependent on US aid. Taylor hoped Khánh's appeals to nationalism might backfire by causing his colleagues to fear a future without US funding.[48] The Americans were aware of Khánh's tactics and exploited it by persistently trying to scare his colleagues with the prospect of a military heavily restricted by the absence of US funding.[48] After the December coup, Taylor felt the fear of US abandonment "raised the courage level of the other generals to the point of sacking" Khánh,[49] as many were seen as beholden above all to their desire for personal advancement.[50] In January and February 1965, Khánh sensed he could no longer work with Taylor and the Americans, and that his support in the junta was unreliable, so he began to try to set up secret peace talks with the communists. Planning for discussions was only beginning, but this was unacceptable to the Americans and hardline anti-communists in the junta, as it meant the bombing campaign against North Vietnam would not be possible.[51] When Khánh's plans were discovered, US-encouraged plotting intensified.[52] On February 19–20, a coup occurred, and after the original plot was put down by the Young Turks, they forced Khánh into exile as well.[53] With Khánh out of the way, the bombing campaign started.[54]

Notes

- Karnow, p. 398.

- Moyar (2006), p. 344.

- Langguth, pp. 326–327.

- Karnow, pp. 398–400.

- Moyar (2006), pp. 344–347.

- Moyar (2006), p. 328.

- Kahin, p. 233.

- Moyar (2004), pp. 765–766.

- Moyar (2006), p. 334.

- Kahin, pp. 210–270.

- Moyar (2006), pp. 300–350.

- Kahin, pp. 240–280.

- Moyar (2004), p. 769.

- Kahin, pp. 228–232.

- Jones, pp. 400–430.

- Shaplen, pp. 228–242.

- Shaplen, p. 294.

- Kahin, pp. 232–233.

- "South Viet Nam: The U.S. v. the Generals". Time. 1965-01-01.

- Shaplen, p. 295.

- Moyar (2004), p. 770.

- Karnow, p. 399.

- Langguth, pp. 322–325.

- Kahin, p. 256.

- Hammond, p. 117.

- Sullivan, Patricia (2007-06-26). "South Vietnamese Gen. Nguyen Chanh Thi". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- Kahin, p. 257.

- Moyar (2006), p. 345.

- Kahin, p. 258.

- Moyar (2006), pp. 344–345.

- Jones, pp. 318–321.

- Shaplen, p. 297.

- Moyar (2006), p. 346.

- Shaplen, p. 296.

- Hammond, p. 118.

- Moyar (2004), p. 771.

- Hammond, p. 119.

- Moyar (2006), p. 347.

- Kahin, pp. 294–299.

- Hammond, p. 120.

- Hammond, p. 121.

- Moyar (2006), p. 348.

- Steinberg, p. 91.

- Hammond, p. 122.

- Moyar (2006), p. 350.

- Shaplen, p. 298.

- Kahin, pp. 255–259.

- Kahin, pp. 296–297.

- Kahin, p. 297.

- Kahin, p. 296.

- Kahin, pp. 292–297.

- Kahin, pp. 296–298.

- Kahin, pp. 298–303.

- Kahin, pp. 303–310.

References

- Hammond, William M. (1988). Public Affairs : The Military and the Media, 1962–1968. Washington, D.C.: Center for Military History, United States Army. ISBN 0-16-001673-8.

- Jones, Howard (2003). Death of a Generation: How the Assassinations of Diem and JFK Prolonged the Vietnam War. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505286-2.

- Kahin, George McT. (1986). Intervention: How America Became Involved in Vietnam. New York City: Knopf. ISBN 0-394-54367-X.

- Karnow, Stanley (1997). Vietnam: A History. New York City: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-84218-4.

- Langguth, A. J. (2000). Our Vietnam: The War, 1954–1975. New York City: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-684-81202-9.

- Moyar, Mark (2004). "Political Monks: The Militant Buddhist Movement during the Vietnam War". Modern Asian Studies. New York City, New York: Cambridge University Press. 38 (4): 749–784. doi:10.1017/S0026749X04001295.

- Moyar, Mark (2006). Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954–1965. New York City: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-86911-0.

- Shaplen, Robert (1966). The Lost Revolution: Vietnam 1945–1965. London: André Deutsch. OCLC 460367485.

- Steinberg, Blema S. (1996). Shame and Humiliation: Presidential Decision Making on Vietnam. Montreal, Quebec: McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 0-7735-1392-2.