De Doctrina Christiana (Milton)

De Doctrina Christiana (On Christian Doctrine) is a theological treatise of the English poet and thinker John Milton (1608–1674), containing a systematic exposition of his religious views. The Latin manuscript “De Doctrina” was found in 1823 and published in 1825. The authorship of the work is debatable. In favor of the theory of the non-authenticity of the text, comments are made both over its content (it contradicts the ideas of his other works, primarily the poems “Paradise Lost” and “Paradise Regained”), as well as since it is hard to imagine that such a complex text could be written by a blind person (Milton was blind by the time of the work's creation, thus it is now assumed that an amanuensis aided the author.) However, after nearly a century of interdisciplinary research, it is generally accepted that the manuscript belongs to Milton. The course of work on the manuscript, its fate after the death of the author, and the reasons for which it was not published during his lifetime are well established. The most common nowadays point of view on De Doctrina Christiana is to consider it as a theological commentary on poems.[1]

The history and style of Christian Doctrine have created much controversy. Critics have argued about the authority of the text as representative of Milton's philosophy based on possible problems with its authorship, its production, and over what its content actually means. As Lieb has shown "... I do not think we shall ever know conclusively whether or not Milton authored all of the De Doctrina Christiana, part of it, or none of it."[2]

Both Charles R. Sumner and John Carey have translated the work into English. Sumner's edition was first printed in 1825. This was the only translation until Carey's in 1973.

Background

The only manuscript of Christian Doctrine was found during 1823 in London's Old State Paper Office (at the Middle Treasury Gallery in Whitehall).[3] The work was one of many in a bundle of state papers written by John Milton while he served as Secretary of Foreign Tongues under Oliver Cromwell. The manuscript was provided with a prefatory epistle that explains the background and history to the formation of the work. If it is genuine, the manuscript is the same work referred to in Milton's Commonplace Book and in an account by Edward Phillips, Milton's nephew, of a theological "tractate".[3]

Because Milton was blind, the manuscript of De Doctrina Christiana was the work of two people: Daniel Skinner and Jeremie Picard.[4] Picard first copied the manuscript from previous works and Skinner prepared the work to be copied for typesetting, although there are a few unidentified editors who made changes to the manuscript.[4] After Milton died in 1674, Daniel Skinner was given Christian Doctrine along with Milton's other manuscripts.[5] In 1675, Skinner attempted to publish the work in Amsterdam, but it was rejected, and in 1677 he was pressured by the English government to hand over the document upon which it was then hidden.[5]

There have been three published translations of De Doctrina Christiana. The first was the Charles edition first produced in 1825, titled A treatise on Christian doctrine compiled from the Holy Scriptures alone.[6] The original Latin text was included alongside the English translation.[6] However, the next translation produced by Carey was not in a dual language format.[7] The latest translation, a collaborative work between John Hale and J. Donald Cullington, works from a new transcription of the original manuscript, and publishes the Latin and English translation in a facing-page format. All three of these translations identify Milton as the author.[6][7]

There is a minority line of criticism that denies Christian Doctrine as a work produced by Milton, but these critics have suggested no authors in place of Milton.[8] These denials are grounded in the assumptions that a blind Milton would struggle to rely on so many Biblical quotations and that the Christian Doctrine is the sole reason why Milton is viewed as having a heterodox theological understanding.[8] In response to this argument, many critics have focused on defending Milton's authorship e.g. Lewalski and Fallon. The argument also fails to account for the high Biblical literacy of the time. Currently many scholars support Miltonic authorship of the piece, and most editions of Milton's prose include the work.[9]

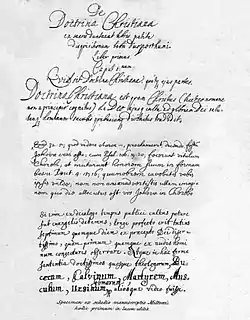

Manuscript

The Christian Doctrine is divided into two books. The first book is then divided into 33 chapters and the second into 17.

The first part of the work appears to be "finished" because it is free of edits and the handwriting (Skinner's) is neat, whereas the second is filled with edits, corrections, and notes in the margins.[10] Skinner's incomplete fair copy has stirred controversy over the work, because it does not provide critics with the ability to determine what the fair copy was based on.[11]

The manuscript itself is patterned on the theological treatises common to Milton's time, such as William Ames's Medulla Theologica and John Wolleb's Compendium Theologiae Christianae.[12] Although Milton refers to "forty-two works", of these many were what he called "systematic theologies" in his various works. Christian Doctrine does not allude to them in the same way as Milton's political treatises.[13] However, the actual pattern of discourse found within the treatise is modeled after Ames's and Wolleb's works even if the content is different.[14]

Where Milton differs is in the use of scripture as evidence. Milton relies on scripture as the basis of his argument and keeps scripture in the center of his text, whereas many other theological treatises keep scriptural passages to the margins.[15] In essence, as Lieb says, "Milton privileges the proof-text over that which is to be proven."[16] Schwartz has gone so far as to claim that Milton "ransacked the whole Bible" and that Milton's own words are "squeezed out of his text."[17] However, the actual "proof-texts" of the Bible are various: no single version is used in Milton's Latin citations.[18]

Theology

Milton's approach to theology is to deal directly with the Bible and use "the word of God" as his basis.[19] Even though Milton relied on the pattern of "theological systems" of his day, he believed that there could be "progress" achieved in understanding theology by relying on the Bible completely.[20] Milton "filled" his theology with direct quotes from the Bible in order to separate his work from his contemporaries who did not deal with the Bible enough for his taste.[20] Some critics have argued that Milton's theology is Arian.[21]

Christian Doctrine

The first chapter of Christian Doctrine discusses the actual meaning of "Christian Doctrine." Milton claims that this "Christian Doctrine" needs to be understood before one can begin to talk about divinity and that the doctrine comes from Christ's communication to mankind about divinity.[22] The doctrine requires humans to "come to terms with God's nature" and it comes from "the ever-abiding desire to celebrate [God's] glory because of his redemptive plan."[23]

Milton's approach to Christian doctrine is not philosophical, and Milton does not attempt at "knowing" God.[23] Instead, we have to find God "in the Holy Scriptures alone and with the Holy Spirit as guide."[24] Milton grounds his message in Christian teaching when he says:

- "I do not teach anything new in this work. I am only to assist the reader's memory by collecting together as it were, into a single book texts which are scattered here and there throughout the Bible, and by systematizing them under definite headings in order to make reference easy"[24]

As such, Milton promotes the idea that his whole work comes only from the teachings of Christ, and that Christian doctrine can only come from Christ.[25]

Milton's God

Milton's version of God is characterized by the darker aspects of deus absconditus.[26] Milton's God is an "over-whelming force" that, in some of Milton's works, appears "as the embodiment of dread."[26] Along with this, God is not definable, but some of his aspects are knowable: he is one, omnipresent, and eternal.[27]

Milton's interpretation of God has been described as Arian. Kelley explains the actual usage of this term as he says, "Milton may be quite correctly called an Arian if he holds an anti-Trinitarian view of God; and it is in this sense that scholars have been calling Milton an Arian since the publication of the De Doctrina in 1825."[28] In particular, Christian Doctrine denies the eternity of the Son, Jesus's pre-birth title.[29] Such a denial separates the unity between God and the Son.[30] However, some claim that Milton did believe that the Son is eternal, since he was begotten before time, and that he represents part of the Logos.[29] But this cannot be, as Kelley points out, "Milton concludes, the Son was begotten not from eternity but 'within the limits of time.'"[31] Although some have argued that the Son is equal in some respects with God, the Son lacks the complete attributes of God.[32]

Another aspect of Milton's God is that he is material. This is not to say that he has a human form, as Milton states, "God in his most simple nature is a SPIRIT."[33] However, such "spirits" to Milton, as with many of his contemporaries like Thomas Hobbes, are a type of material.[34] God, from his material essence, is able to establish all other matter and then manipulate that matter to create forms and beings.[35]

Critical response

In the mid 20th century, C. A. Patrides declared Christian Doctrine as a "theological labyrinth" and as "an abortive venture into theology."[36] The style of organisation has been identified as (in large part) Ramist, or at least compatible with the elaborate charting by Ramean trees common in some of the systematic and scholastic Calvinist theologies of the early seventeenth century.[37]

Notes

- Lewalski B. K., Shawcross J. T., Hunter W. B. (1992). "Forum: Milton's Christian Doctrine". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 32: 143–166. doi:10.2307/450945. JSTOR 450945.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Lieb,"De Doctrina Christiana and the Question of Authorship" (2002), p. 172.

- Complete Poetry and Essential Prose Intro to Christian Doctrine

- Lieb p. 18

- Campbell et al.

- Sumner trans.

- Carey trans.

- Hunter p. 130

- Campbell Milton and the Manuscript of De Doctrina Christiana

- Lieb pp. 19-20

- Lieb p. 20

- Lieb p. 22

- Kelley Prose 21, 22 note 25

- Kelley pp. 27; 38

- Lieb p. 41

- Lieb p. 42

- Schwartz p. 232

- Lieb p. 44

- Lieb p. 23

- Lieb pp. 23–24

- Bauman

- Lieb p. 45

- Lieb p. 46

- Christian Doctrine Ch. 1

- Lieb p. 47

- Lieb p. 8

- Campbell "The Son of God" p. 508

- Kelley "Milton and the Trinity" p. 316

- Kelley "Milton and the Trinity" p. 317

- Campbell "The Son of God" p. 513

- Kelley "Milton and the Trinity" p. 318

- Campbell "The Son of God" pp. 510; 507

- The Complete Poetry and Essential Prose p. 1149

- Reesing pp. 160–161

- Reesing p. 162

- Patrides pp. 106; 108

- Campbell, Gordon; Corns, Thomas N.; Hale, John K.; Holmes, David; and Tweedie, Fiona (5 October 1996). "Milton and De Doctrina Christiana" Archived 27 April 2013 at WebCite. Bangor University. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

References

- Bauman, Michael. Milton's Arianism. Peter Lang. 1987.

- Campbell, Gordon; Corns, Thomas N.; Hale, John K.; Holmes, David; and Tweedie, Fiona. "The Provenance of De Doctrina Christiana", Milton Quarterly 31 (1997) pp. 67–117

- ---- Milton and the Manuscript of De Doctrina Christiana Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2008. 240 pp.

- Campbell, Gordon. "The Son of God in De Doctrina Christiana and Paradise Lost" The Modern Language Review, Vol. 75, No. 3 (Jul. 1980), pp. 507–514

- Falcone, F. (2010). More challenges to Milton's authorship of De doctrina Christiana. Acme: annali della Facoltà di lettere e filosofia dell'Università degli studi di Milano, 63(1), 231-250.

- Fallon, Stephen. "Milton's Arminianism and the Authorship of De Doctrina Christiana" Texas Studies in Literature and Language 41, No. 2 (1999), pp. 103–127

- Hunter, William B. "The Provenance of the Christian Doctrine". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900, Vol. 32, No. 1, The English Renaissance (Winter, 1992), pp. 129–142

- Kelley, Maurice. This Great Argument. Gloucester, Mass.: P. Smith, 1962.

- ---- "Milton and the Trinity" The Huntington Library Quarterly, Vol. 33, No. 4 (Aug. 1970), pp. 315–320

- Lewalski, Barbara. "Milton and De Doctrina Christiana: Evidences of Authorship", Milton Studies 36 (1998), pp. 203–228

- Lieb, Michael. Theological Milton: Deity, Discourse and Heresy in the Miltonic Canon. Pittsburg: Duquesne University Press. 2006. 348 pp.

- ---- "De Doctrina Christiana and the Question of Authorship", Milton Studies 41 (2002) pp. 172–230

- Milton, John. The Complete Poetry and Essential Prose ed. William Kerrigan, John Rumrich, and Stephen Fallon. New York: The Modern Library. 2007. 1365 pp.

- ---- The Complete Prose Works of John Milton. Vol 6. Christian Doctrine ed. Maurice Kelley. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1953-1982.

- ---- A treatise on Christian doctrine compiled from the Holy Scriptures alone trans. Charles Richard Sumner. Cambridge: J. Smith. 1825.

- ---- Christian Doctrine. Vol. VI, Complete Prose Works of John Milton. Ed. Maurice Kelley, trans. John Carey. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1973.

- Patrides, C. A. "Paradise Lost and the Language of Theology", Language and Style in Milton: A Symposium in Honor of the Tercentenary of "Paradise Lost", ed. Ronald David Emma and John T. Shawcross. New York: Frederick Unger. 1967.

- Reesing, John "The Materiality of God in Milton's De Doctrina Christiana" The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 50, No. 3 (Jul. 1957), pp. 159–173

- Schwartz, Regina M. "Citation, Authority, and De Doctrina Christiana", in Politics, Poetics, and Hermeneutics in Milton's Prose ed. David Loewenstein and James Turner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1990

Further reading

- Patrides, C. A. Milton and the Christian Tradition (Oxford, 1966) ISBN 0-208-01821-2

- Patrides, C. A. Bright Essence: Studies in Milton's Theology (University of Utah, 1971) ISBN 0-8357-4382-9

- Patrides, C. A. Selected Prose by John Milton (University of Missouri, 1985) ISBN 0-8262-0484-8