David Martin Long

David Martin Long (July 15, 1953 – December 8, 1999) was an American murderer executed by lethal injection in Texas for the stabbing deaths of three women. He received media attention after he was placed on life support for a drug overdose two days before his scheduled execution. The New York Times said that the medical personnel who treated Long "found themselves in the odd situation of trying to restore to good health a man with only two days left to live."[1]

David Martin Long | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 15, 1953 |

| Died | December 8, 1999 (aged 46) |

| Cause of death | Executed by lethal injection |

| Conviction(s) | Capital murder |

| Details | |

| Victims | Unknown; confessed to involvement in seven deaths |

| State(s) |

|

Date apprehended | October 24, 1986 |

A native of Texas, Long grew up mostly in California. He began getting into legal trouble early in life, was admitted to a California reformatory as a preteen, and spent many years addicted to drugs. In 1986, Long killed three women in Lancaster, Texas; he was apprehended a few weeks later, and was convicted of capital murder and sent to death row. He was never tried for any other murders, but while in police custody for the murders in Lancaster, he had confessed to killing a gas station attendant in a 1978 beating in San Bernardino, California, and to setting a 1983 fire that killed his former boss in Bay City, Texas.

While on death row in 1990, Long confessed to setting another fire; this 1986 blaze in West Texas had resulted in the deaths of two women. A man named Ernest Willis was already on death row for the crime. Long's confession was ultimately found to lack credibility, but it sparked new interest in the validity of Willis's conviction. Arson investigators reopened the case; after several years of investigation, they concluded that an electrical issue most likely caused the fire. Willis was released from prison in 2004, having spent 17 years on death row.

On December 6, 1999, two days before Long was to be executed, he took an overdose of prescription drugs and was hospitalized in Galveston, Texas, where he required breathing assistance from a ventilator. Officials in Texas refused to delay his execution. Long's condition improved significantly by the day after the overdose. He was placed on a medically supervised flight back to death row in Huntsville on December 8, and he was executed that day as scheduled.

Early life

Long was born in Tom Green County, Texas.[2] He lived in California as a child and began to get in trouble with law enforcement at an early age.[3] Long's brother and sister said that their father was an abusive alcoholic who often neglected them. They said that their mother died when Long was ten years old and that Long's behavior became more problematic at that point. Long was sent to foster homes, and he was enrolled in a reformatory by the age of 12. He began regularly drinking alcohol around that time, and he subsequently used illicit drugs, including heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine, for many years.[4]

As a young adult, Long worked as an installation technician for cable television companies in Texas. One of his coworkers later said that Long made a strong first impression on people because of his good looks and blue eyes. Another coworker said that Long had a demanding personality when he was working under the influence of drugs.[5]

Triple murder

On September 19, 1986, after being expelled from an alcohol rehabilitation program in Little Rock, Arkansas, Long was hitchhiking when 37-year-old Donna Sue Jester gave him a ride and allowed him to stay at her home in Lancaster, Texas.[6] Jester lived with her 64-year-old blind and bedridden adoptive mother, Dalpha Lorene Jester, and with 20-year-old Laura Lee Owens.[nb 1][3] Long and Owens began a romantic relationship.[4] Like Long, Owens was a transient who had been allowed to stay in the Jester home.[9]

The three women were killed with a steak knife and a hatchet on September 27, but their bodies were not discovered for two days. Based on crime scene evidence, police officers believed that Long killed Donna Sue and Dalpha Jester first. They said that Owens came home after the other two women had been killed. She is thought to have seen the dead women and then to have been killed while trying to leave the home. Long left the house in the station wagon belonging to Donna Sue Jester.[9]

Arrest, release, and recapture

The night of the murders, Long was arrested for drunken driving in Leon County, Texas, about 100 miles south of Lancaster. He was still driving Donna Sue Jester's vehicle, heading north in a southbound lane on Interstate 45. Officers said that Long was acting like he was under the influence of alcohol or drugs. He had run several cars off the road, banged his head on the police car until he was bleeding, and was "ranting and raving about Jesus or God."[10]

Long told Leon County jailers about killing the three women in Lancaster. However, the women's bodies had not been discovered, so Long's story was not taken seriously and he was released from jail on September 29.[8] A jailer said that before Long's release, he woke up Sheriff Royce Wilson; the jailer said he was told to forget about Long's murder claims. Wilson later said that no one told him about a possible murder confession.[11] Police in Lancaster discovered the murdered women's bodies the same day Long was released from jail.[12] Long became a suspect when officers in Lancaster found a diary entry by Donna Sue Jester that described how she met him and allowed him to move in with her.[3] He was apprehended in Austin for public intoxication on October 24. He had hitchhiked, and the driver called police when Long passed out in the vehicle.[nb 2][7]

While he was in police custody, Long granted an interview to The Dallas Morning News in which he confessed to killing the three women in Lancaster. He said that he "just got tired of hearing all the bickering" from the women, and he said that the women had objected to his drinking. "I've got something in my head that clicks sometimes. It just goes off," he said.[13] Long said that he was not bothered by committing the murders, saying that he felt like he was watching a movie during the killings.[13]

In the same interview with The Dallas Morning News, Long confessed to the murders of gas station attendant James Carnell in San Bernardino, California, and Long's former boss, Bob Neal Rogers, in Bay City, Texas. Long said that Carnell's 1978 murder occurred after Carnell had overcharged him for the repair of a tire. He said he beat Carnell with a tire iron and then shoved a broom handle down Carnell's throat.[4] Rogers, who died in 1983 after his mobile home was set on fire, had angered Long by accusing him of misuse of a company vehicle. Long had been arrested shortly after the Bay City fire, but a grand jury had found insufficient evidence for an indictment at the time.[13]

Long said he thought his criminal tendencies would get better with time, but he noticed that they were getting worse. He said that Texas seemed to fairly dispense the death penalty, and he indicated that he was "pretty much ready to call it a day" because of his demented personality, saying that he did not belong in society.[13] "I think I need to go ahead and leave," he continued. "I like to call it being put to sleep, kind of like they do to animals."[13]

Trial

For the murders of the three women in Lancaster, Long was indicted by a Dallas County grand jury in November 1986. He entered a plea of not guilty, claiming insanity.[4] His trial began in January 1987. Defense attorneys requested a change of venue out of Dallas County.[14] However, the trial proceeded in Dallas.[4]

Long's defense team built their defense around his psychiatric history, including schizophrenia, and his reported head injuries. Before the trial, Long told a psychiatrist that Donna Jester's home had a foul smell and that he became agitated around foul odors because he associated them with his mother's death. Long suspected that dead bodies were buried behind Jester's home. He said that he retrieved the hatchet on the day of the murders because he thought the three women in the Jester home were conspiring against him. The women were trying to jeopardize his relationship with Owens, he said.[4]

On the witness stand, Long said he believed that some of his actions were related to being possessed by Satan.[4] Psychologist William Hester testified for the defense, stating that Long was likely psychotic – and may have been hallucinating from alcohol withdrawal – at the time of the crime. The prosecution pointed to inconsistencies between two of Hester's interviews with Long, and they highlighted one of Hester's earlier written notes, which said Hester found no evidence that Long was insane.[4] Testifying for the state, psychiatrist James Grigson said that Long had antisocial personality disorder, which he said was not considered a mental disease or defect. Grigson said that Long could distinguish right from wrong at the time of the crime.[4]

While the court was in session on February 4, Long stood up and yelled to the jury that he was guilty, saying that he had never wanted to advance the insanity defense in the first place.[15] Long first asked Judge Larry Baraka if he was allowed to change his plea from not guilty to no contest. Then, against the advice of his attorneys, he asked to be able to enter a guilty plea. Judge Baraka noted Long's request without ruling on whether he would instruct the jury to automatically find Long guilty.[16]

Long was convicted of murder on February 7, 1987.[4] At Long's request, his attorneys did not present any evidence during the punishment phase.[17] The jury sentenced him to the death penalty on February 10, 1987.[18]

Time on death row

Three years after arriving on death row, Long gave investigators a three-hour confession in which he admitted to starting a 1986 house fire that killed two women in the West Texas town of Iraan. Ernest Willis had been found guilty of that crime, and he had been sentenced to the death penalty in 1987. The prosecutor in the case had described the evidence against Willis as circumstantial. Long refused to testify before an appeals court in the Willis case. The videotape of Long's confession was thought to be admissible in court, but it would only be effective if evidence could be located to corroborate Long's story.[19]

Long's confession helped the Willis case to attract more attention from attorneys. Appeals lawyers spent several years looking for evidence to support Long's version of the events. Witnesses and arson experts said that several details in the case were consistent with Long's confession, including his admission to the prior arson in Bay City and an analysis that showed the Iraan fire could have been accelerated with a mixture of Everclear and Wild Turkey as Long claimed.[20]

In 2004, Willis was released from prison because new fire investigators looked at the case and determined that the fire was more likely caused by an electrical problem than by arson. According to author Welsh White, Long's confession was probably untrue but it was "the catalyst that precipitated the massive investigation that resulted in Willis's exoneration."[21]

In Long's own death penalty case, he lost a 1991 appeal to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. The next year, the U.S. Supreme Court denied his request for writ of certiorari. His execution was scheduled for September 1992, but two days before he was set to die, he received a stay of execution to pursue further appeals.[4]

Overdose

Long exhausted his appeals and was scheduled for execution on December 8, 1999. Two days before the scheduled execution, Long was found unresponsive after taking an overdose of antipsychotic medication. He was placed on life support and admitted to an intensive care unit in Galveston, Texas.[1] On December 7, Long improved enough that his breathing tube was able to be removed.[1]

On December 8, the day of Long's scheduled execution, Long remained on oxygen but his condition was upgraded from critical to serious, and state officials asked intensive care physician Alexander Duarte to sign an affidavit stating that it would be safe to transport Long to Huntsville. Duarte refused, saying that under normal circumstances Long would have stayed in intensive care for another day or two. The doctor warned that Long still required continual medical care. That same day, state officials arranged a medically supervised transport from Galveston to Huntsville via airplane so that he could be executed as scheduled.[1]

Execution

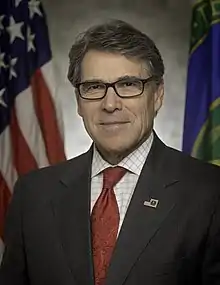

Having found no relief from appellate courts, Long's attorneys asked for clemency from the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles; this request was also denied. Long's legal team appealed to Governor George W. Bush for a 30-day stay of execution because of Long's hospitalization. Bush was out of state campaigning for the Republican presidential nomination, so Lt. Governor Rick Perry was left with the decision. Perry refused to grant a stay, and a spokesperson for Bush said that the governor agreed with Perry's decision. The U.S. Supreme Court rejected Long's final appeal, and he was taken to the execution chamber. He was executed, as scheduled, on December 8, 1999.[1]

Long gave a last statement, saying:

Ah, just ah sorry y'all. I think of tried everything I could to get in touch with y'all to express how sorry I am. I, I never was right after that incident happened. I sent a letter to somebody, you know a letter outlining what I feel about everything. But anyway I just wanted, right after that apologize to you. I'm real sorry for it. I was raised by the California Youth Authority, I can't really pin point where it started, what happened but really believe that's just the bottom line, what happened to me was in California. I was in their reformatory schools and penitentiary, but ah they create monsters in there. That's it, I have nothing else to say. Thanks for coming Jack.[22]

Notes

Explanatory footnotes

Citations

- Yardley, Jim (December 9, 1999). "Texan who took overdose is executed". The New York Times.

- "Offender information: David Long". Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- Graczyk, Michael (December 8, 1999). "David Long executed in Texas". AP News Archive.

- "Media Advisory: David Martin Long scheduled to be executed". texasattorneygeneral.gov. December 7, 1999. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- "Drug problem makes 'handsome' murder suspect a threat: Workers". The Tyler Courier-Times. October 3, 1986.

- Pugh, Carol (October 5, 1986). "Victim was searching for mother". The Times.

- "Texas ax-slaying suspect arrested". The Times (Shreveport). October 25, 1986.

- Pugh, Carol (October 3, 1986). "Search ends in murder". The News-Press.

- "Murder warrant issued for transient in ax murders". AP News. October 1, 1986.

- "Police say ax murder suspect bragged in jail". The Tyler Courier-Times. October 2, 1986. p. 8.

- "Suspect let out of jail despite his boasts of being a killer". AP News. October 2, 1986.

- "Suspect in 3 killings boasted while in jail". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. October 2, 1986.

- "Suspect confesses, wants to be executed". The Times (Shreveport). October 27, 1986.

- "Defense aims to shift trial in triple slaying". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. January 12, 1987.

- "Man convicted in ax slayings". The Times (Shreveport). February 8, 1987.

- "Testimony proceeds despite confession". Tyler Morning Telegraph. February 5, 1987.

- "Man gets death penalty in murder of three women". AP News. February 10, 1987.

- "Ax killer sentenced". The News Journal. February 11, 1987.

- White, pp. 59–60.

- White, p. 60.

- White, pp. 65–66.

- "Death Row Information: David Long". Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

References

- White, Welsh S. (2009). Litigating in the Shadow of Death: Defense Attorneys in Capital Cases. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472021591.