Dagon

Dagon (Phoenician: 𐤃𐤂𐤍, romanized: Dāgūn; Hebrew: דָּגוֹן, Dāgōn) or Dagan (Sumerian: 𒀭𒁕𒃶, romanized: dda-gan[1]) is an ancient Mesopotamian and ancient Canaanite deity. He appears to have been worshipped as a fertility god in Ebla, Assyria, Ugarit, and among the Amorites.

| Dagon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Region | ancient Mesopotamia and ancient Canaan |

| Consort | Shala or Ishara |

| Deities of the ancient Near East |

|---|

| Religions of the ancient Near East |

The Hebrew Bible mentions him as the national god of the Philistines with temples at Ashdod and elsewhere in Gaza.[2]

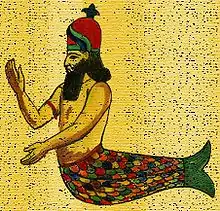

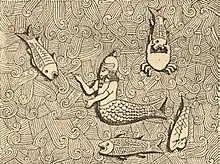

A long-standing association with a Canaanite word for "fish" (as in Hebrew: דג, Tib. /dɔːg/), perhaps going back to the Iron Age, has led to an interpretation as a "fish-god", and the association of "merman" motifs in Assyrian art (such as the "Dagon" relief found by Austen Henry Layard in the 1840s). The god's name derives from the root *dgn 'to be cloudy', implying that he was originally a weather-god.[3] His being associated with clouds, and thus with rain indicates his strong role as an agricultural god.

Name

The name is recorded as Ugaritic Dgn (Dagnu or Daganu), Akkadian Dagana.

According to Philo of Byblos, the Phoenician author Sanchuniathon explained Dagon as a word for "grain" (siton). Sanchuniathon further explains: "And Dagon, after he discovered grain and the plough, was called Zeus Arotrios." The word arotrios means "ploughman" or "pertaining to agriculture" (from ἄροτρον, 'plow').

The theory relating the name to the Hebrew word "fish", based solely upon a reading of 1 Samuel 5:2–7, is discussed in § Fish-god tradition below.

Ancient Near East

Bronze Age

The god Dagon first appears in extant records about 2500 BC in the Mari texts and in personal Amorite names in which the Mesopotamian gods Ilu (Ēl), Dagan, and Adad are especially common.

At Ebla (Tell Mardikh), from at least 2300 BC, Dagan was the head of the city pantheon comprising some 200 deities and bore the titles BE-DINGIR-DINGIR, "Lord of the gods" and Bekalam, "Lord of the land". His consort was known only as Belatu, "Lady". Both were worshipped in a large temple complex called E-Mul, "House of the Star". One entire quarter of Ebla and one of its gates were named after Dagan. Dagan is called ti-lu ma-tim, "dew of the land" and Be-ka-na-na, possibly "Lord of Canaan". He was called lord of many cities: of Tuttul, Irim, Ma-Ne, Zarad, Uguash, Siwad, and Sipishu.

Dagan is mentioned occasionally in early Sumerian texts but becomes prominent only in later Assyro-Babylonian inscriptions as a powerful and warlike protector, sometimes equated with Enki. Dagan's wife was in some sources the goddess Shala (also named as wife of Adad and sometimes identified with Ninmah). In other texts, his wife is Ishara. In the preface to his famous law code, King Hammurabi calls himself "the subduer of the settlements along the Euphrates with the help of Dagan, his creator". An inscription about an expedition of Naram-Sin to the Cedar Mountain relates (ANET, p. 268): "Naram-Sin slew Arman and Ibla with the 'weapon' of the god Dagan who aggrandizes his kingdom."

An interesting early reference to Dagan occurs in a letter to King Zimri-Lim of Mari, 18th century BC, written by Itur-Asduu an official in the court of Mari and governor of Nahur (the Biblical city of Nahor) (ANET, p. 623). It relates a dream of a "man from Shaka" in which Dagan appeared. In the dream, Dagan blamed Zimri-Lim's failure to subdue the King of the Yaminites upon Zimri-Lim's failure to bring a report of his deeds to Dagan in Terqa. Dagan promises that when Zimri-Lim has done so: "I will have the kings of the Yaminites [coo]ked on a fisherman's spit, and I will lay them before you."

In Ugarit around 1300 BC, Dagon had a large temple and was listed third in the pantheon following a father-god and Ēl, and preceding Ba`al Ṣapān (that is the god Haddu or Hadad/Adad). Joseph Fontenrose first demonstrated that, whatever their deep origins, at Ugarit Dagon was sometime identified with El,[4] explaining why Dagan, who had an important temple at Ugarit is so neglected in the Ras Shamra mythological texts, where Dagon is mentioned solely in passing as the father of the god Hadad (Ba'al), but Anat, El's daughter, is Ba'al's sister, and why no temple of El has appeared at Ugarit. It is suspected that Dagon was one of the "seventy sons of El and Athirat" that later sired Hadad (Ba'al) who would eventually attempt to forcefully insert himself in the second-tier of the council of El (although he would ultimately fail in this attempt)

Dagan was sometimes used in Mesopotamian royal names. Two kings of the pre-Babylonian Dynasty of Isin were Iddin-Dagan (c. 1974–1954 BC) and Ishme-Dagan (c. 1953–1935 BC). The latter name was later used by two Assyrian kings: Ishme-Dagan I (c. 1782–1742 BC) and Ishme-Dagan II (c. 1610–1594 BC).

Iron Age

The stele of the 9th century BC Assyrian emperor Ashurnasirpal II (ANET, p. 558) refers to Ashurnasirpal as the favorite of Anu and of Dagan. In an Assyrian poem, Dagan appears beside Nergal and Misharu as a judge of the dead. A late Babylonian text makes him the underworld prison warder of the seven children of the god Emmesharra.

The Phoenician inscription on the sarcophagus of King Eshmunʿazar of Sidon (5th century BC) relates (ANET, p. 662): "Furthermore, the Lord of Kings gave us Dor and Joppa, the mighty lands of Dagon, which are in the Plain of Sharon, in accordance with the important deeds which I did."

Sanchuniathon reportedly made Dagon the brother of Cronus, both sons of the Sky (Uranus) and Earth (Gaia), but not truly Hadad's father. Hadad (Demarus) was begotten by "Sky" on a concubine before Sky was castrated by his son Ēl, whereupon the pregnant concubine was given to Dagon. Accordingly, Dagon in this version is Hadad's half-brother and stepfather.

The Byzantine Etymologicon Magnum lists Dagon as the Phoenician Cronus.[5]

Hebrew Bible

In the Hebrew Bible, Dagon is particularly the god of the Philistines with temples at Beth-dagon in the territory of the tribe of Asher (Joshua 19.27), and in Gaza (see Judges 16.23, which tells soon after how the temple is destroyed by Samson as his last act). Another temple, located in Ashdod, was mentioned in 1 Samuel 5:2–7 and again as late as 1 Maccabees 10.83 and 11.4. King Saul's head was displayed in a temple of Dagon after his death (1 Chronicles 10:8–10). There was also a second place known as Beth-Dagon in Judah (Joshua 15.41).

The first-century Jewish historian Josephus mentions a place named Dagon above Jericho.[6] Jerome mentions Caferdago between Diospolis and Jamnia. There is also a modern Beit Dejan south-east of Nablus. Some of these toponyms may have to do with grain rather than the god.

The account in 1 Samuel 5.2–7 relates how the Ark of the Covenant was captured by the Philistines and taken to Dagon's temple in Ashdod. The following morning the Ashdodites found the image of Dagon lying prostrate before the ark. They set the image upright, but again on the morning of the following day they found it prostrate before the ark, but this time with head and hands severed, lying on the miptān translated as "threshold" or "podium". The account continues with the puzzling words raq dāgôn nišʾar ʿālāyw, which means literally "only Dagon was left to him." (The Septuagint, Peshitta, and Targums render "Dagon" here as "trunk of Dagon" or "body of Dagon", presumably referring to the lower part of his image.)

Thereafter we are told that neither the priests nor anyone else ever steps on the miptān of Dagon in Ashdod "unto this day". "We have remarkable evidence of the permanence of the custom in Zephaniah 1:9, where the Philistines are described as 'those that leap on, or more correctly over, 'the threshold'".[7] This story is depicted on the frescoes of the Dura-Europos synagogue as the opposite to a depiction of the High Priest Aaron and the Temple of Solomon.

Marnas

The vita of Porphyry of Gaza, mentions the great god of Gaza, known as Marnas (Aramaic Marnā the "Lord"), who was regarded as the god of rain and grain and invoked against famine. Marna of Gaza appears on coinage of the time of Hadrian.[8] He was identified at Gaza with Cretan Zeus, Zeus Krētagenēs. It is likely that Marnas was the Hellenistic expression of Dagon. His temple, the Marneion—the last surviving great cult center of paganism—was burned by Cynegius on the orders of the emperor during the persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire in 402. Treading upon the sanctuary's paving-stones had been forbidden. Christians later used these same to pave the public marketplace.

Dagon is still mentioned as a figure of cultic worship in the First Book of Ethiopian Maccabees (12:12), which was composed sometime in the 4th century AD.[9]

Fish-god tradition

The "fish" etymology was accepted in 19th and early 20th century scholarship. This led to the association with the "merman" motif in Assyrian and Phoenician art (e.g. Julius Wellhausen, William Robertson Smith), and with the figure of the Babylonian Oannes (Ὡάννης) mentioned by Berossus (3rd century BC).

The first to cast doubt on the "fish" etymology was Schmökel (1928), who suggested that while Dagon was not in origin a "fish god", the association with dâg "fish" among the maritime Canaanites (Phoenicians) would have affected the god's iconography.[10] Fontenrose (1957:278) still suggests that Berossos's Odakon, part man and part fish, was possibly a garbled version of Dagon. Dagon was also equated with Oannes.

The association with dāg/dâg 'fish' is made by 11th-century Jewish Bible commentator Rashi.[11] In the 13th century, David Kimhi interpreted the odd sentence in 1 Samuel 5.2–7 that "only Dagon was left to him" to mean "only the form of a fish was left", adding: "It is said that Dagon, from his navel down, had the form of a fish (whence his name, Dagon), and from his navel up, the form of a man, as it is said, his two hands were cut off." The Septuagint text of 1 Samuel 5.2–7 says that both the hands and the head of the image of Dagon were broken off.[12]

—Roman imperial period An abundance of material and literary sources indicate that the cult of Marnas was associated with the ancient city of Gaza, located in the Eastern Mediterranean on what is today Palestine. According to Taco Terpstra, the literary texts represent Marnas as a "sky god who also performed oracles. Ancient authors equate him with Cretan Zeus, but the tradition seems to be Hellenistic in date."(Terpstra, p. 182). The depictions of Marnas in coin iconography is not consistent. At times he is shown naked, similar to a naked and bearded Zeus, either seated on a throne or standing while holding a lightning bolt. Other images show Marnas holding a bow, standing on a pedestal in front of a female deity. Regardless of the variety of depictions, the abundance of them on coins indicates that the inhabitants of Gaza held him in high esteem and associated this god with their city. (Terpstra, 182). Gazan overseas traders were still adhering to this cult well into the fifth century CE (Terpstra p.186).

–In Christian literature Marnas is mentioned in the works of the fourth century scholar and theologian Jerome, in several stories from his Life of St. Hilarion, written around 390 CE, in which he condemns his adherents as idolatrous and as "enemies of God." Violent sentiments against the cult of Marnas and the destruction of his temple in Gaza are described by Mark the Deacon, in his account of the life of the early fifth-century saint Porphyry of Thessalonica (Vita Porphyri). After the destruction of Marnas's temple, Mark the deacon petitioned the emperor Arcadius through his wife Eudoxia to grant a request to have all pagan temples in Gaza destroyed(Terpstra, p. 184-5). This request was eventually granted, and after all temples had been destroyed, Porphyry built a church over the ruins of Marnas's temple with financial and other assistance from empress Eudoxia.

In popular culture

The Semitic god Dagon has appeared in many works of popular culture.

Notable examples include John Milton's epic poems Samson Agonistes and Paradise Lost, Dagon and The Shadow Over Innsmouth by H. P. Lovecraft, Dagon by Fred Chappell, and Middlemarch by George Eliot.

Notes

- The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature

- Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges on Judges 16:23.

- Hutter, Manfred (1996). Religionen in der Umwelt des Alten Testaments I. Köln: Kohlhammer. p. 129. ISBN 3-17-012041-7.

- Joseph Fontenrose, "Dagon and El" Oriens 10.2 (December 1957), pp. 277-279.

- Fontenrose 1957:277.

- Antiquities 12.8.1; War 1.2.3

- Pulpit Commentary on 1 Samuel 5, accessed 24 April 2017.

- R.A. Stewart Macalister, The Philistines (London) 1914, p. 112 (illus.).

- Curtin, D.P. (2019-01-08). The First Book of Ethiopian Maccabees: with additional commentary. Dalcassian Publishing Company. ISBN 978-88-295-9233-3.

- H. Schmökel, Der Gott Dagan (Borna-Leipzig) 1928.

- Rashi's commentary on 1 Samuel 5:2

- Noticed by Schmökel 1928, noted in Fontenrose 1957:278.

References

- ANET = Ancient Near Eastern Texts, 3rd ed. with Supplement (1969). Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03503-2.

- Souvay, C., Dagon, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1908)

- "Dagon" in Etana: Encyclopædia Biblica Volume I A–D: Dabarah–David (PDF).

- Feliu, Lluis (2003). The God Dagan in Bronze Age Syria, trans. Wilfred G. E. Watson. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-13158-2.

- Fleming, D. (1993). "Baal and Dagan in Ancient Syria", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie 83, pp. 88–98.

- Matthiae, Paolo (1977). Ebla: An Empire Rediscovered. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-22974-8.

- Pettinato, Giovanni (1981). The Archives of Ebla. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-13152-6.

- Singer, I. (1992). "Towards an Image of Dagan, the God of the Philistines." Syria 69: 431–450.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Dagon". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Dagon". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Terpstra, Taco. Trade in the Ancient Mediterranean: Private Order and Public Institutions. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dagon. |