Amenhotep III

Amenhotep III (Ancient Egyptian: imn-ḥtp(.w) "Amun is Satisfied";[4] Hellenized as Amenophis III), also known as Amenhotep the Magnificent, was the ninth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. According to different authors, he ruled Egypt from June 1386 to 1349 BC, or from June 1388 BC to December 1351 BC/1350 BC,[5] after his father Thutmose IV died. Amenhotep III was Thutmose's son by a minor wife, Mutemwiya.[6]

| Amenhotep III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nibmu(`w)areya,[1] Mimureya, Amenophis III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Amenhotep III wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt, the nemes with cobra and the ceremonial beard | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1391–1353 or 1388–1351 BC (18th Dynasty) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Thutmose IV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Akhenaten | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Tiye Gilukhepa Tadukhepa Sitamun Iset Nebetnehat? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Akhenaten Thutmose Sitamun Iset Henuttaneb Nebetah Smenkhkare? "The Younger Lady" Beketaten (?) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Thutmose IV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Mutemwiya | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1353 BC or 1351 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | WV22 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Malkata, Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III, Colossi of Memnon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

His reign was a period of unprecedented prosperity and splendour, when Egypt reached the peak of its artistic and international power. When he died in the 38th or 39th year of his reign, his son initially ruled as Amenhotep IV, but then changed his own royal name to Akhenaten.

Family

The son of the future Thutmose IV (the son of Amenhotep II) and a minor wife Mutemwiya, Amenhotep III was born around 1401 BC.[7] He was a member of the Thutmosid family that had ruled Egypt for almost 150 years since the reign of Thutmose I. Amenhotep III was the father of two sons with his Great Royal Wife Tiye. Their first son, Crown Prince Thutmose, predeceased his father and their second son, Amenhotep IV, later known as Akhenaten, ultimately succeeded Amenhotep III to the throne. Amenhotep III also may have been the father of a third child—called Smenkhkare, who later would succeed Akhenaten and briefly ruled Egypt as pharaoh.

Amenhotep III and Tiye may also have had four daughters: Sitamun, Henuttaneb, Isis or Iset, and Nebetah.[8] They appear frequently on statues and reliefs during the reign of their father and also are represented by smaller objects—with the exception of Nebetah.[9] Nebetah is attested only once in the known historical records on a colossal limestone group of statues from Medinet Habu.[10] This huge sculpture, that is seven meters high, shows Amenhotep III and Tiye seated side by side, "with three of their daughters standing in front of the throne—Henuttaneb, the largest and best preserved, in the centre; Nebetah on the right; and another, whose name is destroyed, on the left."[8]

Amenhotep III elevated two of his four daughters—Sitamun and Isis—to the office of "great royal wife" during the last decade of his reign. Evidence that Sitamun already was promoted to this office by Year 30 of his reign, is known from jar-label inscriptions uncovered from the royal palace at Malkata.[8] Egypt's theological paradigm encouraged a male pharaoh to accept royal women from several different generations as wives to strengthen the chances of his offspring succeeding him.[11] The goddess Hathor herself was related to Ra as first the mother and later wife and daughter of the god when he rose to prominence in the pantheon of the Ancient Egyptian religion.[8]

Amenhotep III is known to have married several foreign women:

- Gilukhepa, the daughter of Shuttarna II of Mitanni, in the tenth year of his reign.[12]

- Tadukhepa, the daughter of his ally Tushratta of Mitanni, Around Year 36 of his reign.[13][14]

- A daughter of Kurigalzu, king of Babylon.[14]

- A daughter of Kadashman-Enlil, king of Babylon.[14]

- A daughter of Tarhundaradu, ruler of Arzawa.[14]

- A daughter of the ruler of Ammia (in modern Syria).[14]

Life

Amenhotep III has the distinction of having the most surviving statues of any Egyptian pharaoh, with over 250 of his statues having been discovered and identified. Since these statues span his entire life, they provide a series of portraits covering the entire length of his reign.

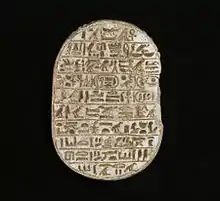

Another striking characteristic of Amenhotep III's reign is the series of over 200 large commemorative stone scarabs that have been discovered over a large geographic area ranging from Syria (Ras Shamra) through to Soleb in Nubia. [15] Their lengthy inscribed texts extol the accomplishments of the pharaoh. For instance, 123 of these commemorative scarabs record the large number of lions (either 102 or 110 depending on the reading) that Amenhotep III killed "with his own arrows" from his first regnal year up to his tenth year. [16] Similarly, five other scarabs state that the foreign princess who would become a wife to him, Gilukhepa, arrived in Egypt with a retinue of 317 women. She was the first of many such princesses who would enter the pharaoh's household. [16]

Another eleven scarabs record the excavation of an artificial lake he had built for his Great Royal Wife, Queen Tiye, in his eleventh regnal year,

Regnal Year 11 under the Majesty of... Amenhotep (III), ruler of Thebes, given life, and the Great Royal Wife Tiye; may she live; her father's name was Yuya, her mother's name Tuya. His Majesty commanded the making of a lake for the great royal wife Tiye—may she live—in her town of Djakaru. (near Akhmin). Its length is 3,700 (cubits) and its width is 700 (cubits). (His Majesty) celebrated the Festival of Opening the Lake in the third month of Inundation, day sixteen. His Majesty was rowed in the royal barge Aten-tjehen in it [the lake].[17]

Amenhotep appears to have been crowned while still a child, perhaps between the ages of 6 and 12. It is likely that a regent acted for him if he was made pharaoh at that early age. He married Tiye two years later and she lived twelve years after his death. His lengthy reign was a period of unprecedented prosperity and artistic splendour, when Egypt reached the peak of her artistic and international power. Proof of this is shown by the diplomatic correspondence from the rulers of Assyria, Mitanni, Babylon, and Hatti which is preserved in the archive of Amarna Letters; these letters document frequent requests by these rulers for gold and numerous other gifts from the pharaoh. The letters cover the period from Year 30 of Amenhotep III until at least the end of Akhenaten's reign. In one famous correspondence—Amarna letter EA 4—Amenhotep III is quoted by the Babylonian king Kadashman-Enlil I in firmly rejecting the latter's entreaty to marry one of this pharaoh's daughters:

From time immemorial, no daughter of the king of Egy[pt] is given to anyone.[18]

Amenhotep III's refusal to allow one of his daughters to be married to the Babylonian monarch may indeed be connected with Egyptian traditional royal practices that could provide a claim upon the throne through marriage to a royal princess, or, it could be viewed as a shrewd attempt on his part to enhance Egypt's prestige over those of her neighbours in the international world.

The pharaoh's reign was relatively peaceful and uneventful. The only recorded military activity by the king is commemorated by three rock-carved stelae from his fifth year found near Aswan and Saï (island) in Nubia. The official account of Amenhotep III's military victory emphasizes his martial prowess with the typical hyperbole used by all pharaohs.

Regnal Year 5, third month of Inundation, day 2. Appearance under the Majesty of Horus: Strong bull, appearing in truth; Two Ladies: Who establishes laws and pacifies the Two Lands;...King of Upper and Lower Egypt: Nebmaatra, heir of Ra; Son of Ra: [Amenhotep, ruler of Thebes], beloved of [Amon]-Ra, King of the Gods, and Khnum, lord of the cataract, given life. One came to tell His Majesty, "The fallen one of vile Kush has plotted rebellion in his heart." His Majesty led on to victory; he completed it in his first campaign of victory. His Majesty reached them like the wing stroke of a falcon, like Menthu (war god of Thebes) in his transformation...Ikheny, the boaster in the midst of the army, did not know the lion that was before him. Nebmaatra was the fierce-eyed lion whose claws seized vile Kush, who trampled down all its chiefs in their valleys, they being cast down in their blood, one on top of the other.[19]

Amenhotep III celebrated three Jubilee Sed festivals, in his Year 30, Year 34, and Year 37 respectively at his Malkata summer palace in Western Thebes. [20] The palace, called Per-Hay or "House of Rejoicing" in ancient times, comprised a temple of Amun and a festival hall built especially for this occasion. [20] One of the king's most popular epithets was Aten-tjehen which means "the Dazzling Sun Disk"; it appears in his titulary at Luxor temple and, more frequently, was used as the name for one of his palaces as well as the Year 11 royal barge, and denotes a company of men in Amenhotep's army. [21]

There is a myth on the divine birth of Amenhotep III which is depicted in the Luxor Temple. In this myth, Amenhotep III is sired by Amun, who has gone to Mutemwiya in form of Thutmosis IV. [22][23]

Proposed co-regency by Akhenaten

There is currently no conclusive evidence of a co-regency between Amenhotep III and his son, Akhenaten. A letter from the Amarna palace archives dated to Year 2—rather than Year 12—of Akhenaten's reign from the Mitannian king, Tushratta, (Amarna letter EA 27) preserves a complaint about the fact that Akhenaten did not honor his father's promise to forward Tushratta statues made of solid gold as part of a marriage dowry for sending his daughter, Tadukhepa, into the pharaoh's household.[24] This correspondence implies that if any co-regency occurred between Amenhotep III and Akhenaten, it lasted no more than a year.[25] Lawrence Berman observes in a 1998 biography of Amenhotep III that,

It is significant that the proponents of the coregency theory have tended to be art historians [e.g., Raymond Johnson], whereas historians [such as Donald Redford and William Murnane] have largely remained unconvinced. Recognizing that the problem admits no easy solution, the present writer has gradually come to believe that it is unnecessary to propose a coregency to explain the production of art in the reign of Amenhotep III. Rather the perceived problems appear to derive from the interpretation of mortuary objects.[26]

In February 2014, the Egyptian Ministry for Antiquities announced what it called "definitive evidence" that Akhenaten shared power with his father for at least 8 years, based on findings from the tomb of Vizier Amenhotep-Huy.[27][28] The tomb is being studied by a multi-national team led by the Instituto de Estudios del Antiguo Egipto de Madrid and Dr Martin Valentin. The evidence consists of the cartouches of Amenhotep III and Akhenaten being carved side by side, but this may only suggest that Amenhotep III had chosen his only surviving son Akhenaten to succeed him since there are no objects or inscriptions known to name and give the same regnal dates for both kings.

The Egyptologist Peter Dorman also rejects any co-regency between these two kings, based on the archaeological evidence from the tomb of Kheruef.[29]

Final years

Reliefs from the wall of the temple of Soleb in Nubia and scenes from the Theban tomb of Kheruef, Steward of the King's Great Wife, Tiye, depict Amenhotep as a visibly weak and sick figure.[30] Scientists believe that in his final years he suffered from arthritis and became obese. It has generally been assumed by some scholars that Amenhotep requested and received, from his father-in-law Tushratta of Mitanni, a statue of Ishtar of Nineveh—a healing goddess—in order to cure him of his various ailments, which included painful abscesses in his teeth.[31] A forensic examination of his mummy shows that he was probably in constant pain during his final years due to his worn and cavity-pitted teeth. However, more recent analysis of Amarna letter EA 23 by William L. Moran, which recounts the dispatch of the statue of the goddess to Thebes, does not support this popular theory. The arrival of the statue is known to have coincided with Amenhotep III's marriage with Tadukhepa, Tushratta's daughter, in the pharaoh's 36th year; letter EA 23's arrival in Egypt is dated to "regnal year 36, the fourth month of winter, day 1" of his reign.[32] Furthermore, Tushratta never mentions in EA 23 that the statue's dispatch was meant to heal Amenhotep of his maladies. Instead, Tushratta merely writes,

Say to Nimmureya [i.e., Amenhotep III], the king of Egypt, my brother, my son-in-law, whom I love and who loves me: Thus Tušratta, the king of Mitanni, who loves you, your father-in-law. For me all goes well. For you may all go well. For your household for Tadu-Heba [i.e., Tadukhepa], my daughter, your wife, who you love, may all go well. For your wives, for your sons, for your magnates, for your chariots, for your horses, for your troops, for your country, and for whatever else belongs to you, may all go very, very well. Thus Šauška of Nineveh, mistress of all lands: "I wish to go to Egypt, a country that I love, and then return." Now I herewith send her, and she is on her way. Now, in the time, too, of my father,...[she] went to this country, and just as earlier she dwelt there and they honored her, may my brother now honor her 10 times more than before. May my brother honor her, [then] at [his] pleasure let her go so that she may come back. May Šauška (i.e., Ishtar), the mistress of heaven, protect us, my brother and me, a 100,000 years, and may our mistress grant both of us great joy. And let us act as friends. Is Šauška for me alone my god[dess], and for my brother not his god[dess]?[33]

The likeliest explanation is that the statue was sent to Egypt "to shed her blessings on the wedding of Amenhotep III and Tadukhepa, as she had been sent previously for Amenhotep III and Gilukhepa."[34] As Moran writes:

One explanation of the goddess' visit is that she was to heal the aged and ailing Egyptian king, but this explanation rests purely on analogy and finds no support in this letter... More likely, it seems, is a connection with the solemnities associated with the marriage of Tušratta's daughter; sf. the previous visit mentioned in lines 18f., perhaps on the occasion of the marriage of Kelu-Heba [i.e., Gilukhepa]...and note, too, Šauška's role along with Aman, of making Tadu-Heba answer to the king's desires.[35]

The contents of Amarna letter EA21 from Tushratta to his "brother" Amenhotep III strongly affirms this interpretation. In this correspondence, Tushratta explicitly states,

I have given...my daughter [Tadukhepa] to be the wife of my brother, whom I love. May Šimige and Šauška go before her. May they m[ake he]r the image of my brother's desire. May my brother rejoice on t[hat] day. May Šimige and Šauška grant my brother a gre[at] blessing, exquisi[te] joy. May they bless him and may you, my brother, li[ve] forever.[36]

Death

_(1904)_-_front_edited_-_TIMEA.jpg.webp)

Amenhotep III's highest attested regnal date is Year 38, which appears on wine jar-label dockets from Malkata.[37] He may have lived briefly into an unrecorded Year 39, dying before the wine harvest of that year.[38]

Amenhotep III was buried in the Western Valley of the Valley of the Kings, in Tomb WV22. Sometime during the Third Intermediate Period his mummy was moved from this tomb and was placed in a side-chamber of KV35 along with several other pharaohs of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties where it lay until discovered by Victor Loret in 1898.

An examination of his mummy by the Australian anatomist Grafton Elliot Smith concluded that the pharaoh was between 40 and 50 years old at death.[39] His chief wife, Tiye, is known to have outlived him by at least twelve years, as she is mentioned in several Amarna letters dated from her son's reign as well as depicted at a dinner table with Akhenaten and his royal family in scenes from the tomb of Huya, which were made during Year 9 and Year 12 of her son's reign.[40][41]

Foreign leaders communicated their grief at the pharaoh's death, with Tushratta saying:

When I heard that my brother Nimmureya had gone to his fate, on that day I sat down and wept. On that day I took no food, I took no water.[42]

When Amenhotep III died, he left behind a country that was at the very height of its power and influence, commanding immense respect in the international world; however, he also bequeathed an Egypt that was wedded to its traditional political and religious certainties under the Amun priesthood.[43]

The resulting upheavals from his son Akhenaten's reforming zeal would shake these old certainties to their very foundations and bring forth the central question of whether a pharaoh was more powerful than the existing domestic order as represented by the Amun priests and their numerous temple estates. Akhenaten even moved the capital away from the city of Thebes in an effort to break the influence of that powerful temple and assert his own preferred choice of deities, the Aten. Akhenaten moved the Egyptian capital to the site known today as Amarna (though originally known as Akhetaten, 'Horizon of Aten'), and eventually suppressed the worship of Amun.[44]

The Court

There were many important individuals in the court of Amenhotep III. Viziers were Ramose, Amenhotep, Aperel and Ptahmose. They are known from a remarkable series of monuments, including the well known tomb of Ramose at Thebes. Treasurers were another Ptahmose and Merire. High stewards were Amenemhat Surer and Amenhotep (Huy). Viceroy of Kush was Merimose. He was a leading figure in the military campaigns of the king in Nubia. Perhaps the most famous official of the king was Amenhotep, son of Hapu. He never had high titles but was later worshipped as god and main architect of some of the king's temples.[45] Priests of Amun under the king included the brother-in-law of the king Anen and Simut.

Monuments

Amenhotep III built extensively at the temple of Karnak including the Luxor temple which consisted of two pylons, a colonnade behind the new temple entrance, and a new temple to the goddess Ma'at. Amenhotep III dismantled the Fourth Pylon of the Temple of Amun at Karnak to construct a new pylon—the Third Pylon—and created a new entrance to this structure where he erected two rows of columns with open papyrus capitals down the centre of this newly formed forecourt. The forecourt between the Third and Fourth Pylons, sometimes called an obelisk court, was also decorated with scenes of the sacred barque of the deities Amun, Mut, and Khonsu being carried in funerary boats.[46] The king also started work on the Tenth Pylon at the Temple of Amun there. Amenhotep III's first recorded act as king—in his Years 1 and 2—was to open new limestone quarries at Tura, just south of Cairo and at Dayr al-Barsha in Middle Egypt in order to herald his great building projects.[47] He oversaw the construction of another temple to Ma'at at Luxor and virtually covered Nubia with numerous monuments.

...including a small temple with a colonnade (dedicated to Thutmose III) at Elephantine, a rock temple dedicated to Amun "Lord of the Ways" at Wadi es-Sebuam, and the temple of Horus of Miam at Aniba...[as well as founding] additional temples at Kawa and Sesebi.[48]

His enormous mortuary temple on the west bank of the Nile was, in its day, the largest religious complex in Thebes, but unfortunately, the king chose to build it too close to the floodplain and less than two hundred years later, it stood in ruins. Much of the masonry was purloined by Merneptah and later pharaohs for their own construction projects.[49] The Colossi of Memnon—two massive stone statues, 18 m (59 ft) high, of Amenhotep that stood at the gateway of his mortuary temple—were the only elements of the complex that remained standing. Amenhotep III also built the Third Pylon at Karnak and erected 600 statues of the goddess Sekhmet in the Temple of Mut, south of Karnak.[50]Some of the most magnificent statues of New Kingdom Egypt date to his reign "such as the two outstanding couchant rose granite lions originally set before the temple at Soleb in Nubia" as well as a large series of royal sculptures.[51] Several beautiful black granite seated statues of Amenhotep wearing the nemes headress have come from excavations behind the Colossi of Memnon as well as from Tanis in the Delta.[51] In 2014, two giant statues of Amenhotep III that were toppled by an earthquake in 1200 BC were reconstructed from more than 200 fragments and re-erected at the northern gate of the king's funerary temple.[52]

One of the most stunning finds of royal statues dating to his reign was made as recently as 1989 in the courtyard of Amenhotep III's colonnade of the Temple of Luxor where a cache of statues was found, including a 6 feet (1.8 m)-high pink quartzite statue of the king wearing the Double Crown found in near-perfect condition.[51] It was mounted on a sled, and may have been a cult statue.[51] The only damage it had sustained was that the name of the god Amun had been hacked out wherever it appeared in the pharaoh's cartouche, clearly done as part of the systematic effort to eliminate any mention of this god during the reign of his successor, Akhenaten.[51]

Sed Festival Stela of Amenhotep III

The Sed Festival dates from the dawn of Egyptian kingship with early Egyptian kings of the Old Kingdom.[53] When a king served 30 years of his reign, he performed a series of tests to demonstrate his fitness for continuing as pharaoh. On completion, the king's rejuvenated vitality enabled him to serve three more years before holding another Sed Festival. To commemorate an event, a stela, which is a stone of various size and composition, is inscribed with highlights of the event. Proclamations informed the people living in Egypt of an upcoming Sed Festival together with stelae.

Stela

A Sed Festival Stela of Amenhotep III (Hellenized as Amenophis III) was taken from Egypt to Europe by an art dealer. It is now believed to be in the United States but not on public display.[54] In Europe, Dr. Eric Cassirer at one time owned the stela. The dimensions of the white alabaster stela are 10 x 9 cm (3.94 x 3.54 in), but only the upper half of the stela survived.[55] It was shaped in the form of a temple pylon with a gradual narrowing near the top.

Front view: The god Heh, who represents the number one million, holds notched palm leaves signifying years.[55] Above his head, Heh appears to support the cartouche of Amenhotep III symbolically for a million years.

Side view: A series of festival (ḥb) emblems together with a Sed (sd) emblem identifying the stela as one made for Amenhotep III's Sed Festival royal jubilee.[55]

Top view: The top shows malicious damage to the stela where the cartouche was chipped away.

Back view: Like the top view, the cartouche has been eradicated.

Cassirer suggests Akhenaten, Amenhotep III's son and successor, was responsible for defacing the king's name on the stela.[56] Akhenaten detested his royal family name so much, he changed his own name from Amenhotep IV to Akhenaten; he vandalized any reference to the god Amun since he had chosen to worship another god, the Aten.[56] Other gods displayed on the stela, Re and Ma’at, showed no sign of vandalism.[56]

The stela is believed to have been displayed prominently in Akhenaten's new capital city of Akhetaten (current day Amarna).[56] With the royal name and Amun references removed, it likely had a prominent place in a temple or palace of Akhenaten.[56] Akhenaten could then display the stela without reminders of his old family name or the false god Amun, yet celebrate his father's achievement.

Amenhotep III's Sed Festival

Amenhotep wanted his Sed Festivals to be far more spectacular than those of the past.[57] He served as king for 38 years, celebrating three Sed Festivals during his reign. Rameses II set the record for Sed Festivals with 14 during his 67-year reign.

Amenhotep III appointed Amenhotep, son of Hapu, as the official to plan the ceremony. Amenhotep-Hapu was one of the few courtiers still alive to have served at the last Sed Festival (for Amenhotep II).[57] Amenhotep-Hapu enlisted scribes to gather information from records and inscriptions of prior Sed Festivals, often from much earlier dynasties. Most of the descriptions were found in ancient funerary temples.[57] In addition to the rituals, they collected descriptions of costumes worn at previous festivals.

Temples were built and statues erected up and down the Nile. Craftsmen and jewelers created ornaments commentating the event including jewelry, ornaments, and stelae.[57] Malqata, "House of Rejoicing", the temple complex built by Amenhotep III, served as the focal point for the Sed Festivals.[58] Malqata featured an artificial lake that Amenhotep built for his wife, Queen Tiye, that would be used in the Sed Festival.

The scribe Nebmerutef coordinated every step of the event.[59] He directed Amenhotep III to use his mace to knock on the temple doors. Beside him, Amenhotep-Hapu mirrored his effort like a royal shadow.[59] The king was followed by Queen Tiye and the royal daughters. When moving to another venue, the banner of the jackal god Wepwawet, "Opener of Ways" preceded the King. The king changed his costume at each major activity of the celebration.[59]

One of the major highlights of the Festival was the king's dual coronation. He was enthroned separately for Upper and Lower Egypt. For Upper Egypt, Amenhotep wore the white crown but changed to the red crown for the Lower Egypt coronation.[60]

Based on indications left by Queen Tiye's steward Khenruef, the festival may have lasted two to eight months.[61] Khenruef accompanied the king as he traveled the empire, probably reenacting the ceremony for different audiences.[61]

At the time of the festival Amenhotep III had three official wives: the "Great wife", Queen Tiye; their daughter, Sitamen, who was promoted to be a queen at the time of the Sed Festival; and Gilukhepa, a daughter of the king of Mitanni, a traditional Egyptian rival.[61] No mention is made of the royal harem.

Although shunned by common Egyptians, incest was not uncommon among royalty.[62] In fact, most Egyptian creation stories depend on it. By the time of the Sed Festival, Queen Tiye would be past her child-bearing years.[62] However, a sculpture restored by Amenhotep for his grandfather, Amenhotep II, shows Sitamen with a young prince beside her.[62]

As a reward for a lifetime of serving the Egyptian kings, Amenhotep-Hapu received his own funerary temple.[63] The location was behind that of his king, Amenhotep III. Some of Amenhotep III's workshops were razed to make room for Amenhotep-Hapu's temple.[63]

Some of the known information about Amenhotep's Sed Festival comes from an unlikely source: the trash heap at Malqata Palace. Many jars bearing the names of donors to Amenhotep III to celebrate his festival were found. The donors were not just the rich but also small servants. The jars bear the donor's name, title, and date. The jars were stored without respect to their origin.[64]

After the Sed Festival, Amenhotep III transcended from being a near-god to one divine.[65] Few Egyptian kings lived long enough for their own celebration. Those who survived used the celebration as the affirmation of transition to divinity.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Amenhotep III | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

Granodiorite seated statue of Amenhotep III at the British Museum, from its left side.

Granodiorite seated statue of Amenhotep III at the British Museum, from its left side. Granodiorite statue of Amenhotep III at the British Museum, Left of Statue above.

Granodiorite statue of Amenhotep III at the British Museum, Left of Statue above. Granodiorie Amenhotep (Right Statue) Northeast side, British Museum

Granodiorie Amenhotep (Right Statue) Northeast side, British Museum Granodiorie Amenhotep (Left Statue) Close up, British Museum

Granodiorie Amenhotep (Left Statue) Close up, British Museum Bulls Tail (Left Statue), British Museum

Bulls Tail (Left Statue), British Museum Belt (Left Statue), British Museum

Belt (Left Statue), British Museum Feet (Left Statue), British Museum

Feet (Left Statue), British Museum Left Inscriptions (Left Statue), British Museum

Left Inscriptions (Left Statue), British Museum Right Inscriptions (Left Statue), British Museum

Right Inscriptions (Left Statue), British Museum Red Granite Statue, North East side, British Museum

Red Granite Statue, North East side, British Museum Red Granite Statue, Left side, British Museum

Red Granite Statue, Left side, British Museum Limestone Amenhotep, British Museum

Limestone Amenhotep, British Museum Amenhotep III wearing the red crown of Lower Egypt, c. 1400 BCE. From Thebes, Egypt. British Museum. EA6

Amenhotep III wearing the red crown of Lower Egypt, c. 1400 BCE. From Thebes, Egypt. British Museum. EA6 Amenhotep III wearing the red crown of Lower Egypt, c. 1400 BCE. From Thebes, Egypt. British Museum. EA7

Amenhotep III wearing the red crown of Lower Egypt, c. 1400 BCE. From Thebes, Egypt. British Museum. EA7

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amenhotep III. |

Footnotes

- Moran 1992, p. 7.

- Clayton 1994, p. 112.

- Amenhotep III

- Ranke, Hermann (1935). Die Ägyptischen Personennamen, Bd. 1: Verzeichnis der Namen (PDF). Glückstadt: J.J. Augustin. p. 30. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Beckerath 1997, p. 190.

- O'Connor & Cline 1998, p. 3.

- Fletcher 2000, p. 10.

- O'Connor & Cline 1998, p. 7.

- Kozloff & Bryan 1992, nos. 24, 57, 103 & 104.

- Kozloff & Bryan 1992, fig. II, 5.

- Troy 1986, pp. 103, 107, 111.

- Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 155.

- Fletcher 2000, p. 156.

- Grajetzki 2005.

- O'Connor & Cline 1998, pp. 11–12.

- O'Connor & Cline 1998, p. 13.

- Kozloff & Bryan 1992, no. 2.

- Moran 1992, p. 8.

- Urk. IV 1665–66

- O'Connor & Cline 1998, p. 16.

- O'Connor & Cline 1998, pp. 3, 14.

- O'Connor & Cline 2001.

- Tyldesley 2006.

- Moran 1992, pp. 87–89.

- Reeves 2000, pp. 75–78.

- Berman 1998, p. 23.

- Pharaoh power-sharing unearthed in Egypt Daily News Egypt. February 6, 2014

- Proof found of Amenhotep III-Akhenaten co-regency thehistoryblog.com

- Dorman 2009.

- Grimal 1992, p. 225.

- Hayes 1973, p. 346.

- Aldred 1991, p. 13.

- Moran 1992, pp. 61–62.

- O'Connor & Cline 1998, p. 22.

- Moran 1992, p. 62 n. 2.

- Moran 1992, p. 50.

- Kozloff & Bryan 1992, p. 39, fig. II.4.

- Clayton 1994, p. 119.

- Smith 1912, p. 50.

- "North Tombs at Amarna". Archived from the original on 7 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- O'Connor & Cline 1998, p. 23.

- Fletcher 2000, p. 161.

- Grimal 1992, pp. 223, 225.

- Fletcher 2000, p. 162.

- Lichtheim 1980, p. 104.

- The Obelisk Court of Amenhotep III

- Urk. IV, 1677–1678

- Grimal 1992, p. 223.

- Grimal 1992, p. 224.

- Grimal 1992, pp. 224, 295.

- Clayton 1994, p. 118.

- "Amenhotep III Statues Once More Stand Before Pharaoh's Temple". Latin American Herald Tribute. December 15, 2014.

- Berman 1998, p. 15.

- Cassirer 1952, p. 128.

- Cassirer 1952, p. 129.

- Cassirer 1952, p. 130.

- Kozloff 2012, p. 182.

- Berman 1998, p. 17.

- Kozloff 2012, p. 189.

- Kozloff 2012, p. 190.

- Kozloff 2012, p. 192.

- Kozloff 2012, p. 194.

- Kozloff 2012, p. 197.

- Kozloff 2012, p. 183.

- Kozloff 2012, p. 195.

Bibliography

- Aldred, Cyril (1991). Akhenaten: King of Egypt. Thames & Hudson.

- Allen, James P. "The Amarna Succession" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 1, 2013. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- Beckerath, Jürgen von (1997). Chronologie des Pharaonischen Ägypten. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- Berman, Lawrence M. (1998). "Overview of Amenhotep III and His Reign". In O'Connor, David; Cline, Eric (eds.). Amenhotep III: Perspectives on His Reign. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Cassirer, Manfred (1952). "A hb-sd Stela of Amenophis III". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 38.

- Clayton, Peter (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. Thames & Hudson Ltd.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson.

- Dorman, Peter (2009). "The Long Coregency Revisited: Architectural and Iconographic Conundra in the Tomb of Kheruef" (PDF). Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane. Brill. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-22.

- Fletcher, Joann (2000). Chronicle of a Pharaoh – The Intimate Life of Amenhotep III. Oxford University Press.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2005). Ancient Egyptian Queens: A Hieroglyphic Dictionary. London: Golden House Publications. ISBN 978-0-9547218-9-3.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Books.

- Hayes, William (1973). "Internal affairs from Thutmosis I to the death of Amenophis III". The Middle East and the Aegean Region, c. 1800–1380 BC. Pt 1, Vol 2.

- Kozloff, Arielle; Bryan, Betsy (1992). Royal and Divine Statuary in Egypt's Dazzling Sun: Amenhotep III and his World. Cleveland.

- Kozloff, Arielle P. (2012). Amenhotep III: Egypt's Radiant Pharaoh. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lichtheim, Miriam (1980). Ancient Egyptian Literature: A Book of Readings: The Late Period. University of California Press.

- Moran, William L. (1992). The Amarna Letters. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- O'Connor, David; Cline, Eric (1998). Amenhotep III: Perspectives on His Reign. University of Michigan Press.

- O'Connor, David; Cline, Eric H. (2001). Amenhotep III: Perspectives on His Reign. University of Michigan Press.

- Reeves, Nicholas (2000). Akhenaten: Egypt's False Prophet. Thames & Hudson.

- Smith, Grafton Elliot (1912). The Royal Mummies. Cairo.

- Troy, Lana (1986). "Patterns of Queenship in Ancient Egyptian Myth and History". Uppsala Studies in Ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern Civilizations. 14.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2006). Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. Thames & Hudson.