Cultural depictions of elephants

Elephants have been depicted in mythology, symbolism and popular culture. They are both revered in religion and respected for their prowess in war. They also have negative connotations such as being a symbol for an unnecessary burden. Ever since the Stone Age, when elephants were represented by ancient petroglyphs and cave art, they have been portrayed in various forms of art, including pictures, sculptures, music, film, and even architecture.

Religion, mythology and philosophy

The Asian elephant appears in various religious traditions and mythologies. They are treated positively and are sometimes revered as deities, often symbolising strength and wisdom. Similarly, the African elephant is seen as the wise chief who impartially settles disputes among the forest creatures in African fables,[2] and the Ashanti tradition holds that they are human chiefs from the past.[3]

The Earth is supported and guarded by mythical World Elephants at the compass points of the cardinal directions, according to the Hindu cosmology of ancient India. The classical Sanskrit literature also attributes earthquakes to the shaking of their bodies when they tire. Wisdom is represented by the elephant in the form of the deity Ganesha, one of the most popular gods in the Hindu religion's pantheon. The deity is very distinctive in having a human form with the head of an elephant which was put on after the human head was either was cut off or burned, depending on the version of the story from various Hindu sources. Lord Ganesha's birthday (rebirth) is celebrated as the Hindu festival known as Ganesha Chaturthi.[4] In Japanese Buddhism, their adaptation of Ganesha is known as Kangiten ("Deva of Bliss"), often represented as an elephant-headed male and female pair shown in a standing embrace to represent unity of opposites.[5]

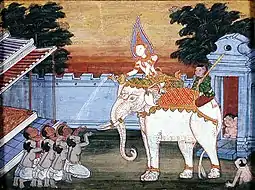

In Hindu iconography, many devas are associated with a mount or vehicle known as a vāhana. In addition to providing a means of transport, they symbolically represent a divine attribute. The elephant vāhana represents wisdom, divine knowledge and royal power; it is associated with Lakshmi, Brihaspati, Shachi and Indra. Indra was said to ride on a flying white elephant named Airavata, who was made the King of all elephants by Lord Indra. A white elephant is rare and given special significance. It is often considered sacred and symbolises royalty in Thailand and Burma, where it is also considered a symbol of good luck. In Buddhist iconography, the elephant is associated with Queen Māyā of Sakya, the mother of Gautama Buddha. She had a vivid dream foretelling her pregnancy in which a white elephant featured prominently.[6] To the royal sages, the white elephant signifies royal majesty and authority; they interpreted the dream as meaning that her child was destined for greatness as a universal monarch or a buddha.[7]

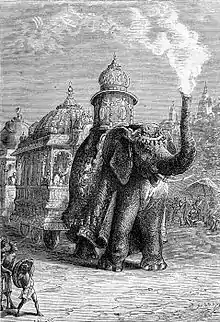

Elephants remain an integral part of religion in South Asia and some are even featured in various religious practices.[8] Temple elephants are specially trained captive elephants that are lavishly caparisoned and used in various temple activities. Among the most famous of the temple elephants is Guruvayur Keshavan of Kerala, India. They are also used in festivals in Sri Lanka such as the Esala Perahera.

In the version of the Chinese zodiac used in Northern Thailand, the last year in the 12-year cycle – called "Year of the Pig" in China – is known instead as "Year of the Elephant", reflecting the importance of elephants in Thai culture.

In Islamic tradition, the year 570 is when the Prophet Muhammad was born and is known as the Year of the Elephant.[9] In that year, Abraha, ruler of Yemen tried to conquer Mecca and demolish the Kaaba, reportedly in retaliation for the previous Meccan defilement of Al–Qalis Church in Sana'a, a cathedral Abraha had constructed.[10] However, his plan was foiled when his white elephant named Mahmud refused to cross the boundary of Mecca. The elephant, who led Abraha's forty thousand men, could not be persuaded with reason or even with violence, which was regarded as a crucial omen by Abraha's soldiers. This is generally related in the five verses of the chapter titled 'The Elephant'[lower-alpha 2] in the Quran.[11]

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, medieval artists depicted the mutual killing of both Eleazar the Maccabee and a war elephant carrying an important Seleucid general as described in the apocryphal book of 1 Maccabees. The early illustrators knew little of the elephant and their portrayals are highly inaccurate.[12]

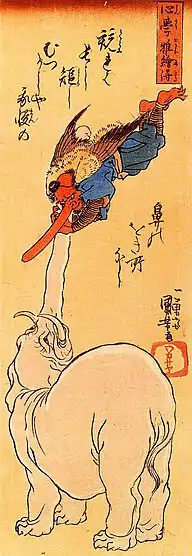

The unfamiliarity with the exotic beast has also made elephants a subject of widely different interpretations thus giving rise to mythological creatures. The story of the blind men and an elephant was written to show how reality may be viewed from differing perspectives. The source of this parable is unknown, but it appears to have originated in India. It has been attributed to Buddhists, Hindus, Jainists, and Sufis, and was also used by Discordians. The scattered skulls of prehistoric dwarf elephants, on the islands of Crete and Sicily may have formed the basis of belief in existence of cyclopes,[lower-alpha 3] the one-eyed giants featured in Homer's Odyssey (c. 800~600 BC). As early as the 1370s, scholars had noted that the skulls feature a large nasal cavity at the front that could be mistaken for a singular eye socket;[13] and the skulls, twice the size of a human's, looked as if they could belong to giant humanoids.[13][14] It is also suggested that the Behemoth described in the Book of Job may be the elephant due to its grazing habits and preference to rivers.[15]

In art

From Stone Age rock-art to Modern age street-art, the elephant has remained a popular subject for artists.

Prehistoric

Prehistoric North Africans depicted the elephant in Paleolithic age rock art. For example, the Libyan Tadrart Acacus, a UNESCO World Heritage site, features a rock carving of an elephant from the last phase of the Pleistocene epoch (12,000–8000 BC)[16] rendered with remarkable realism.[17] There are many other prehistoric examples, including Neolithic rock art of south Oran (Algeria), and a white elephant rock painting in 'Phillip's Cave' by the San in the Erongo region of Namibia.[18] From the Bovidian period[lower-alpha 4] (3550–3070 BCE), elephant images by the San bushmen in the South African Cederberg Wilderness Area suggest to researchers that they had "a symbolic association with elephants" and "had a deep understanding of the communication, behaviour and social structure of elephant family units" and "possibly developed a symbiotic relationship with elephants that goes back thousands of years."[21]

Ancient

Indian rock reliefs include a number of depictions of elephants, notably the Descent of the Ganges at Mahabalipuram, a large 7th-century Hindu scene with many figures that uses the form of the rock to shape the image.[22] At Unakoti, Tripura there is an 11th-century group of reliefs related to Shiva, including several elephants.

Indian painting includes many elephants, especially ones ridden for battle and royal transport in Mughal miniatures.

Modern

Elephants are often featured in modern artistic works, including those by artists such as Norman Rockwell,[23] Andy Warhol[24] and Banksy.[25] The stork-legged elephant, found in many of Salvador Dalí's works,[lower-alpha 5] is one of the surrealist's best known Icons, and adorn the walls of the Dalí Museum in Spain.[26][27][28] Dali used an elephant motif in various works such as Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening, The Elephants and in The Temptation of Saint Anthony. The Elephant and Obelisk motif also found its way to various works by this artist.

Politics and secular society

The elephant is also depicted by various political groups and in secular society.

In Asia

Asian cultures admire the high intelligence and good memory of Asian elephants. As such, they symbolise wisdom[29] and royal power. They are used as a representative of various political parties such as United National Party of Sri Lanka and Bahujan Samaj Party of India. The Elephants of Kerala are an integral part of the daily life in Kerala, South India.[30] These Indian elephants are loved, revered, groomed and given a prestigious place in the state's culture.[31] There they are often referred to as the 'sons of the sahya.' The elephant is the state animal of Kerala and is featured on the emblem of the Government of Kerala. The elephant is also on the flag of the Kingdom of Laos with three elephants visible, supporting an umbrella (another symbol of royal power) until it became a republic in 1975. Other Southeast Asian realms have also displayed one or more white elephants.

The elephant also lends its name to some landmarks in Asia. Elephanta Island (also called "Gharapuri Island") in Mumbai Harbour was given this name by 17th century Portuguese explorers who saw a monolithic basalt sculpture of an elephant near the entrance to what became known as the Elephanta Caves. The Portuguese attempted to take it home with them but ended up dropping it into the sea because their chains were not strong enough. Later, the British moved this elephant to the Victoria and Albert Museum (now Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum) in Mumbai.[32]

In Europe

Aside from being a curiosity for Europeans, the elephant also became a symbol of military might from the experience of fighting foreign powers that fielded war elephants throughout history.[33] In 326 BC after Alexander the Great's victory over King Porus of India, the captured war elephants became a symbol of imperial power, being used as an emblem of the Seleucid Diadoch empire.

In about the year 800 AD, an elephant called Abul Abbas was brought from Bagdhad to Charlemagne's residennce in Aachen [34]

In 1229, the so-called Cremona elephant was presented by Sultan of Egypt Al-Kamil to the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, and the elephant was used by the Emperor in parades.[35] The elephant is mentioned in the visit of Frederick's brother-in-law Richard of Cornwall to Cremona in 1241, in the Chronica Maiora of Matthew Paris. The presence of the animal is also recorded in 1237 in the Cremona city annals.

In 1478, the Order of the Elephant (Danish: Elefantordenen) was founded by King Christian I. This very select religious organization is the highest order of Denmark, and uses the elephant as a symbol of docility, sobriety and piety;[36] instituted in its current form in 1693 by King Christian V.

In the early 1800s Napoleon Bonaparte wanted a monument to his own imperial power, and he decreed that a colossal bronze elephant fountain be cast from guns captured at his victorious Battle of Friedland in 1807. The was for the site where the Bastille once stood.[37]

In 1870, the killing and eating of the elephants Castor and Pollux from the Botanical gardens during the Siege of Paris received considerable attention at the time. This became emblematic of the hardships and degradation caused by siege and war, especially since the two elephants were previously very popular with the Parisian public.

The city of Catania, Sicily has an immemorial connection with the elephant. The local sorcerer Heliodorus, was credited with either riding a magic elephant or transforming himself into this animal. Under medieval Arab rule Catania was known as Medinat-Al-Fil or Balad-Al-Fil (City/State of the Elephant). The symbol of the city is the Fontana dell'Elefante (Fountain of the Elephant) assembled in its present form in 1736 by Giovanni Battista Vaccarini.

In Central London, England, an area known as the "Elephant and Castle" (or "The Elephant") is centered on a major road intersection and a station of the London Underground. The "Castle" in the location's name refers to a medieval European perception of a howdah. The heraldic elephant and castle has also been associated with the city of Coventry, England since medieval times, where it denotes religious symbolism[lower-alpha 6] and with the town of Dumbarton, Scotland.[lower-alpha 7] More recently in Britain, Welephant, a red elephant cartoon character with a fireman's helmet, was originally used as a mascot by fire brigades in the United Kingdom to promote fire safety for children and has become the mascot for the Children's Burn Trust.[39]

In America

The elephant as the symbol for the Republican Party of the United States originated in an 1874 political cartoon of an Asian elephant by Thomas Nast in Harper's Weekly. This cartoon, titled "Third Term Panic", is a parody of Aesop's fable,[lower-alpha 8] "The Ass in the Lion's Skin". It depicts an elephant (labelled The Republican Vote) running toward a chasm of chaos; frightening a jackass[lower-alpha 9] in a lion's skin (labelled Caesarism) which scatters animals representing various interests. Although Nast used the elephant seven more times to represent the "Republican Vote", he did not use it to represent the Republican Party until March 1884 in "The Sacred Elephant".[43]

In Africa

Many African cultures revere the African Elephant as a symbol of strength and power.[44][45] It is also praised for its size, longevity, stamina, mental faculties, cooperative spirit, and loyalty.[46] South Africa, uses elephant tusks in their coat of arms to represent wisdom, strength, moderation and eternity.[47] The elephant is symbolically important to the nation of Ivory Coast (Côte d'Ivoire); the Coat of arms of Ivory Coast features an elephant head escutcheon as its focal point.

In the western African Kingdom of Dahomey (now part of Benin) the elephant was associated with the 19th century rulers of the Fon people, Guezo and his son Glele.[lower-alpha 10] The animal is believed to evoke strength, royal legacy, and enduring memory as related by the proverbs: "There where the elephant passes in the forest, one knows" and "The animal steps on the ground, but the elephant steps down with strength."[48] Their flag depicted an elephant wearing a royal crown.

Ivory Coast coat of arms, (ca 1964–2000)

Ivory Coast coat of arms, (ca 1964–2000).svg.png.webp) Flag of Siam (Thailand), (1855–1916)

Flag of Siam (Thailand), (1855–1916).svg.png.webp) Flag of the Kingdom of Laos, (1952–1975)

Flag of the Kingdom of Laos, (1952–1975) Flag of the Kingdom of Dahomey, (ca 1888)

Flag of the Kingdom of Dahomey, (ca 1888)

Popular culture

The elephant has entered into popular culture through various idiomatic expressions and adages.

The phrase "Elephants never forget" refers to the belief that elephants have excellent memories. The variation "Women and elephants never forget an injury" originates from the 1904 book Reginald on Besetting Sins by British writer Hector Hugh Munro, better known as Saki.[49][50]

This adage seems to have a basis in fact, as reported in Scientific American:

- Remarkable recall power, researchers believe, is a big part of how elephants survive. Matriarch elephants, in particular, hold a store of social knowledge that their families can scarcely do without, according to research conducted on elephants at Amboseli National Park in Kenya.[51]

"Seeing the Elephant" is a 19th-century Americanism denoting a world-weary experience;[52] often used by soldiers, pioneers and adventurers to qualify new and exciting adventures such as the Civil War, the Oregon Trail and the California Gold Rush.[52][53][54] A "white elephant" has become a term referring to an expensive burden, particularly when much has been invested with false expectations. The term 'white elephant sale' was sometimes used in Australia as a synonym for jumble sale. In the U.S., a White elephant gift exchange is a popular winter holiday party activity. The idiom Elephant in the room tells of an obvious truth that no one wants to discuss, alluding to the animal's size compared to a small space. "Seeing pink elephants" refers to a drunken hallucination and is the basis for the Pink Elephants on Parade sequence in the 1941 Disney animated feature, Dumbo. "Jumbo" has entered the English language as a synonym for "large".[lower-alpha 11] Jumbo originally was the name of a huge elephant acquired by circus showman P. T. Barnum from the London Zoo in 1882. The name itself may have come from a West African[lower-alpha 12] native word for "elephant".[55]

Literature

The elephant is viewed in both positive and negative lights in similar fashion as humans in various forms of literature. In fact, Pliny the Elder praised the beast in his Naturalis Historia as one that is closest to a human in sensibilities.[56] The elephant's different connotations clash in Ivo Andrić's novella The Vizier's Elephant. Here the citizens of Travnik despise the young elephant who symbolises the cruelty of the unseen Vizier. However, the elephant itself is young and innocent despite unknowingly causing havoc due to youthful play.[57] In the Tarzan novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Tantor is the generic term for "elephant" in the fictional simian Mangani language, but is associated with a particular elephant who eventually becomes Tarzan's faithful companion. Other elephant characters that are shown in a positive light include Jean de Brunhoff's Babar and Dr. Seuss' Horton. Jules Verne featured a steam-powered mechanical elephant in his 1880 novel The Steam House. In addition, the animal is depicted in its military use through the oliphaunts of J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings trilogy and the alien invaders of Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle's 1985 science fiction novel, Footfall.

Notable short stories featuring elephants include Rudyard Kipling's "Toomai of the Elephants" and "The Elephant's Child"; as well as Mark Twain's "The Stolen White Elephant". George Orwell wrote an allegorical essay, "Shooting an Elephant"; and in "Hills Like White Elephants", Ernest Hemingway used the allegorical white elephant, alluding to a pregnancy as an unwanted gift.[58]

The animal is also seen in historical novels. The Elephant's Journey (Portuguese: A Viagem do Elefante, 2008) is a novel by Nobel laureate[59] José Saramago. This is a fictional account based on an historical 16th century journey from Lisbon to Vienna by an elephant named Solomon.[60] An Elephant for Aristotle is a 1958 historical novel by L. Sprague de Camp. It concerns the adventures of a Thessalian cavalry commander who has been tasked by Alexander the Great to bring an elephant captured from King Porus of India, to Athens as a present for Alexander's old tutor, Aristotle.

Elephants can also represent the hugeness and wildness of the imagination, as in Ursula Dubosarsky's 2012 children's book, Too Many Elephants in This House,[61] which also plays with the notion of the elephant in the room.[62] An imaginary elephant can (perhaps) become real, as with the elusive Heffalump. Although never specified as an elephant in A. A. Milne's Winnie the Pooh stories, a heffalump physically resembles an elephant; and E. H. Shepard's illustration shows an Indian elephant. "Heffalump" has since been defined as "a child's term for an elephant."[63]

Sports

The elephant is used as a mascot or logo for various sports groups.

Circus showman P. T. Barnum donated the stuffed hide of Jumbo the elephant to Tufts University in 1885, where Jumbo soon became the mascot for their sports teams. However, all that remains of Jumbo are some ashes stored in a peanut butter jar and a piece of his tail following a fire in 1975. "Jumbo's spirit lives on" in the peanut butter jar which is ceremoniously passed on to successive Athletic Directors.[64]

The mascot for the Oakland Athletics (A's) baseball team is based on the figurative white elephant. The story of picking the mascot began when New York Giants' manager John McGraw told reporters that Philadelphia manufacturer Benjamin Shibe, who owned the controlling interest in the new team, had a "white elephant on his hands"; manager Connie Mack defiantly adopted the white elephant as the team mascot.[lower-alpha 13] The A's are sometimes, but infrequently, referred to as the 'Elephants' or 'White Elephants'. Their mascot is nicknamed Stomper.

University of Alabama's Crimson Tide mascot has been an elephant since 1930 after a sportswriter wrote of a fan yelling "Hold your horses, the elephants are coming!" as the football team rumbled onto the field.[65] Their elephant-costumed "Big Al" officially debuted at the 1979 Sugar Bowl.

Catania, Italy uses the elephant to represent their football team, referencing the animal that has represented their city since ancient times.

Music

The elephant is also represented in music such as Henry Mancini's hit song "Baby Elephant Walk", which has been described as "musical shorthand for kookiness of any stripe".[66] The American band the White Stripes' fourth album was entitled Elephant in honour of the animal's brute strength and closeness to its relatives.[67] The hit single "Elephant" by British recording artist Alexandra Burke is based on the expression "elephant in the room".[68] "Nellie the Elephant" is a children's song first released in 1956 and since covered by many artists including the punk-rock band Toy Dolls;[69] For her album, Leave Your Sleep, Natalie Merchant set to music "The Blind Men and the Elephant" poem by John Godfrey Saxe, which is based on the parable.[70]

Film and television

The elephant is also featured in film and on television. Thailand has produced various movies about the animal, from the 1940 historical drama film King of the White Elephant to the 2005 martial-arts action film, Tom-Yum-Goong.[lower-alpha 14] In the West, the elephant was popularised by Dumbo, the elephant who learns to fly in the 1941 Disney animated feature of the same name. Kipling's "Toomai of the Elephants" was adapted as the 1937 British adventure film Elephant Boy. In popular modern films, Tai the elephant-actress has portrayed Bo Tat in Operation Dumbo Drop (1995), Vera in Larger than Life (1996) and Rosie in Water for Elephants (2011).

On television, Nellie the Elephant is a 1990 UK cartoon series inspired by the 1956 song of the same name, featuring Scottish singer Lulu voicing Nelly. Britt Allcroft adapted "Mumfie" the elephant from Katherine Tozer's series of children's books,[lower-alpha 15] originally in a '70s televised puppet show and then in the '90s animated Magic Adventures of Mumfie series.

The 2016 action-comedy film The Brothers Grimsby gained notoriety for its crude and graphic elephant scene.[72]

Games

The elephant can also be found in games. In shatranj, the medieval game from which chess developed, the piece corresponding to the modern bishop was known as Pil or Alfil ("Elephant"; from Persian and Arabic,[lower-alpha 16] respectively).[74] In the Indian chaturanga game the piece is also called "Elephant" (Gaja). The same is true in Chinese chess,[lower-alpha 17] which has an elephant piece ("Xiàng", 象) that serves as a defensive piece, being the only one that may not cross the river dividing the game board. In the Japanese shogi version, the piece was known as the "Drunken Elephant"; however, it was dropped by order of the Emperor Go-Nara and no longer appears in the version played in contemporary Japan. Even with modern Chess, the word for the bishop is still Alfil in Spanish, Alfiere in Italian, Feel in Persian, and "Elephant" (Слон) in Russian. All of these games originally simulated a kind of battlefield, thus this piece represented a war elephant. In the present-day canonical Staunton chess set, the piece's deep groove, which originally represented the elephant's tusks, is now regarded as representing a bishop's (or abbot's) mitre.

Architecture

In the 18th-century, French architect Charles Ribart planned to build a three-level elephant building at the Paris site where the Arc de Triomphe was eventually built. Nothing became of this, but in the early 19th-century, Napoleon conceived of an even larger elephant structure, the Elephant of the Bastille. Although the ambitious project was never completed with its intended bronze elephant, a full-sized plaster and wood-frame model stood in its place. After Napoleon's defeat, this structure eventually became a neglected eyesore, and a setting in Victor Hugo's 1862 novel, Les Misérables.

Three multi-story elephant shaped buildings were built in America by James V. Lafferty in the 1880s. The largest, seven-story, thirty-one room Elephantine Colossus served as a hotel, concert hall, and attraction on Coney Island before it burned down in 1896. The six-story Lucy the Elephant is the only remaining of the three, and survives as a tourist attraction near Atlantic City. These giant elephant structures, however, are dwarfed by the 32-story Bangkok Elephant Tower in Thailand. This iconic elephant-inspired building reflects the influence of the elephant in Thai culture.[76]

Gallery

Buddhist parable of the blind monks examining an elephant; illustrated by Itchō Hanabusa. (1888 Ukiyo-e woodcut)

Buddhist parable of the blind monks examining an elephant; illustrated by Itchō Hanabusa. (1888 Ukiyo-e woodcut) A royal white elephant in 19th century Thai art

A royal white elephant in 19th century Thai art

Fontana dell'Elefante (Fountain of the Elephant); Catania's symbol

Fontana dell'Elefante (Fountain of the Elephant); Catania's symbol

Country Gentleman magazine. Norman Rockwell cover, 16 August 1919

Country Gentleman magazine. Norman Rockwell cover, 16 August 1919 African elephant mask (Ivory Coast)

African elephant mask (Ivory Coast) Kuosi Society (Bamileke people) Elephant Mask, Brooklyn Museum

Kuosi Society (Bamileke people) Elephant Mask, Brooklyn Museum

.jpg.webp)

Erawan statue in Chiang Mai, Thailand

Erawan statue in Chiang Mai, Thailand Dernier projet pour la fontaine de l'Éléphant de la Bastille (1809–1810), Watercolor by Jean-Antoine Alavoine

Dernier projet pour la fontaine de l'Éléphant de la Bastille (1809–1810), Watercolor by Jean-Antoine Alavoine 1354 illustration depicting Panchatantra fable: Rabbit fools Elephant by showing the reflection of the moon

1354 illustration depicting Panchatantra fable: Rabbit fools Elephant by showing the reflection of the moon Shang dynasty ceramic elephant, Xinjiang Museum

Shang dynasty ceramic elephant, Xinjiang Museum

See also

- Aung Pinle Hsinbyushin, Lord of the White Elephant of Aung Pinle, a Great Nat of Burma.

- Bholu (mascot), iconic mascot for Indian Railways

- Elephants in ancient China

- Elephants in Kerala culture

- Elephants in Thailand

- Elephant riddle

- Elephant test

- Elephant clock

- Elephant Parade, sculpture exhibit

- Execution by elephant

- Elephants and mice sub-section of Fear of mice article

- Faithful Elephants, story of the elephants in Tokyo's Ueno Zoo during World War II

- Gaja, elephants in ancient Hindu mythology

- Hastin, elephants in Vedic texts.

- Jumbo, 1935 musical and 1962 Film

- Temple elephant

- The Sultan's Elephant, traveling show featuring a huge mechanical elephant

- War elephant

- List of fictional elephants

- List of historical elephants

- National Elephant Day (Thailand)

- Category: Metaphors referring to elephants

Notes

- Ganesha Getting Ready to Throw His Lotus : "In the Mudgalapurāṇa (VII, 70), in order to kill the demon of egotism (Mamāsura) who had attacked him, Gaṇeśa Vighnarāja throws his lotus at him. Unable to bear the fragrance of the divine flower, the demon surrenders to Gaṇeśa."

- Sura 105: Al-Fil (Arabic: سورة الفيل — English: The Elephant)

- The plural of cyclops is cyclopes ("sigh-KLO-peez")[13]

- During the African pastoral 'Bovidian period', there were many depictions of Bovid herds, suggesting the development of animal domestication[19] During this period humans began to domesticate animals, and transition to a seminomadic lifestyle as farmers and herders.[20]

- For example, see: Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening and The Elephants

- "The elephant is seen, not only as a beast so strong that he can carry a tower – Coventry's castle – full of armed men, but also as a symbol of Christ's redemption of the human race."[38]

- cf: Dumbarton Civic Coat of Arms and Dumbarton Football Club crest

- Although the caption quotes the fable, Nast attributes it to —Shakespear or Bacon

- Contrary to popular belief, Nast did not originate the donkey (a derogatory reference to Andrew "Jackass" [Jackson]) as the symbol of the Democratic Party[41][42]

- Guezo and Glele ruled from 1818 to 1858 and from 1858 to 1889, respectively

- As a product size, by 1886 (cigars); Jumbo jet attested by 1964.[55]

- Kongo: Nzamba[55]

- Over the years, the A's elephant mascot has appeared in various colours other than white, and was briefly replaced by a mule

- US title: The Protector, UK title: Warrior King

- The first book Mumfie Marches On, published during World War II (1942) was suggested by the British government; which culminates in the capture of Adolph Hitler by Mumfie and allies[71]

- From Persian پيل pīl; al- is the Arabic for "the"

- Xiangqi (Chinese: 象棋, p Xiàngqí), sometimes translated as "the elephant game".[75]

References

- Plate 39 (23), A guide to the principal gold and silver coins of the ancients, from circ. B.C. 700 to A.D. 1 (1889); British Museum. Dept. of Coins and Medals : "AR. Demetrius"

- "Animal Ways". Nature's Ways Lore, Legend, Fact and Fiction. Newton Abbot: F+W Media. 2006. ISBN 9780715333938. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- "Elephant". Myths, legends, beliefs and traditional stories from Africa. A-gallery. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- "Festivals : Ganesh Chaturthi". Bochasanwasi Shri Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- Sanford, James H. (1991). "Literary Aspects of Japan's Dual-Gaņeśa Cult". In Brown, Robert L. (ed.). Ganesh : studies of an Asian god. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 289. ISBN 978-0791406564.

- "Life of Buddha (part 1) : Queen Maha Maya's Dream". BuddhaNet. Buddha Dharma Education Association.

- ed, Kevin Trainor, general (2004). Buddhism : the illustrated guide. New York: Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0195173987.

- Clarke, Jacqueline L. Schneider ; foreword by Ronald V. (2012). Sold into extinction : the global trade in endangered species. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger. pp. 104. ISBN 978-0313359392.

- Watt, W. Montgomery (1977). Muhammad : prophet and statesman ([Repr] ed.). London: Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0198810780.

- Hajjah Adil, Amina, "Prophet Muhammad", ISCA, 1 Jun 2002, ISBN 1-930409-11-7

- Mir, Mustansir (2005). "Elephants, Birds of Prey, and Heaps of Pebbles: Farāhī's Interpretation of Sūrat al-Fīl". Journal of Qur'anic Studies. 7 (1): 33–47. doi:10.3366/jqs.2005.7.1.33. JSTOR 25728163.

- "Medieval Bestiary : Elephant". Medieval Bestiary. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- "Greek Giants". American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- "Cyclops". Greek and Roman Mythology. Boston: MobileReference.com. 2007. ISBN 9781605010915.

- Slifkin, Natan (2007). "Behold the Behemoth". Sacred monsters : mysterious and mythical creatures of Scripture, Talmud and Midrash. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Zoo Torah. p. 183. ISBN 978-1933143187.

- "Rock-Art Sites of Tadrart Acacus". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- "Were Cavemen Better at Drawing Animals Than Modern Artists?". Science Daily. 5 December 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

Source: reprinted from materials provided by Public Library of Science.

- "Phillip's Cave". Info Namibia. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- etc, edited by Thurstan Shaw (1995). "Rock art and pastoralism". The Archaeology of Africa : food, metals and towns (New ed.). London: Routledge. p. 235. ISBN 978-0415115858.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Shaped Stone of the Sahara". Artsy. Pace Primitive. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Paterson, Andrew (December 2004). "Elephants (!X6 ) of the Cederberg Wilderness Area" (PDF). The Digging Stick. 24 (3): 1–4. ISSN 1013-7521. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176, pp. 278-83

- "Two Boys on an Elephant by Norman Rockwell". Best Norman Rockwell Art.com. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- "African Elephant, 1983 – Andy Warhol". The Endangered Species portfolio. Coskun Fine Art. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- Wyatt, Edward. A Splashy Los Angeles Debut by Banksy – Design – New York Times, Published 16 September 2006. Retrieved 11 December 2012

- "Salvador Dali Gallery – Memories of Surrealism : Space Elephant". SalvadorDaliExperts.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- In Kerala the elephant is a most popular motif in temple and church art, architecture, sculpture. See e.g.George Menachery, The Elephant and the Christians, (Malayalam) South Asia Research Assistance Services, 2014, forward by Madambu Kunjikkuttan)

- "Aanayum Nazraniyum" (PDF).

- Guading, Madonna (2009). The signs and symbols bible : the definitive guide to mysterious markings. New York: Sterling Pub. Co. p. 239. ISBN 978-1402770043.

- Datta, Amaresh (1987). The Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature. One (A To Devo). ISBN 9788126018031.

- Bradnock, Robert; Bradnock, Roma (2000). South India. Footprint Handbooks. p. 4. ISBN 9781900949811.

Elephants Kerala culture.

- HT Cafe, Mumbai, Monday, 4 June 2007 p. 31; Article: "Lord of the Islands" by Jerry Pinto

- Brosius, Maria (2006). The Persians: an introduction (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 200. ISBN 978-0415320894.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abul-Abbas

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cremona_elephant

- Lach, Donald F. (1970). Asia in the making of Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-0226467504.

- Bingham, Denis (1901). The Bastille, Volume 2 (eBook). Princeton University: J. Pott. p. 447.

- "Coat of Arms : History of the Coat of Arms". Coventry City Council. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- "The History of the National Fire Safety Charity for Children". Welephant web site. National Fire Safety Charity for Children. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- Cartoon of the Day: "The Third-Term Panic" Archived 21 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2008-09-01

- "How the parties got their animal symbols". (CBS News). CBS Interactive Inc. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- Dewey, Donald (2007). The art of ill will : the story of American political cartoons. New York: New York University Press. pp. 14–18. ISBN 978-0814719855.

- Kennedy, Robert C. "The Third-Term Panic". Cartoon of the Day. HarpWeek. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- "383. African Elephant (Loxodonta africana)". EDGE: Mammal Species Information. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- "West African Elephants". Convention on Migratory Species. Archived from the original on 10 July 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- "Elephant: The Animal and Its Ivory in African Culture". Fowler Museum at UCLA. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- "National Coat of Arms". South African Government Information. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- "Elephant Figure | Fon peoples | The Met". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

-

English Wikiquote has quotations related to: Saki#Reginald (1904)

English Wikiquote has quotations related to: Saki#Reginald (1904) - Jenkins, Dr. Orville Boyd (1 June 2001). "Why Elephants Never Forget". Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- Ritchie, James. "Fact or Fiction?: Elephants Never Forget". Scientific American. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- Wilton, Dave (13 June 2006). "elephant, to see the". Wordorigins.org. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- "Seeing the Elephant". Historic Nantucket. Nantucket Historical Association. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

Originally published in the Historic Nantucket, Vol 48, no. 3 (Summer 1999), p. 28

- "SEEING THE ELEPHANT". New York Times. 1 March 1861. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- Harper, Douglas. "jumbo". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- Erica Fudge, ed. (2004). Renaissance Beasts: Of Animals, Humans, and Other Wonderful Creatures. University of Illinois Press. pp. 172–173. ISBN 9780252091339.

- "Priča o vezirovom slonu/The Story of the Vizier's Elephant". The Ivo Andrić Foundation. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- Johnston, Kenneth G. (Autumn 1982). "Hills Like White Elephants". Studies in American Fiction. 10 (2): 230–238. doi:10.1353/saf.1982.0019. S2CID 161839831.

- "1998 : José Saramago". The Nobel Prize in Literature. Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- Le Guin, Ursula K (24 July 2010). "The Elephant's Journey by José Saramago". Book of the week. London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- Joyner, Ursula Dubosarsky ; illustrated by Andrew (2012). Too many elephants in this house. Camberwell, Vic.: Penguin Books Australia. p. 32. ISBN 978-0670075461.

- Review by Robin Morrow "Too Many Elephants in This House" Magpies Vol.27 2012 p.8

- "Definition of heffalump in English". Oxford Dictionary. British & World English (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2014.

- "Jumbo the Elephant, Tufts' Mascot". Get to Know Tufts. Tufts University. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- "Big Al". Crimson Tide. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- Mills, Ted. "Henry Mancini : Hatari! : Review". AllMusic. All Media Network.

- DiCrescenzo, Brent (1 April 2003). "The White Stripes: Elephant". Pitchfork. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

The album title refers to the endangered animal's brute power and less honored instinctual memory for dead relatives

- Love, Ryan (10 January 2012). "Alexandra Burke interview: 'Elephant is just the beginning'". Digital Spy. Hearst Magazines UK. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- "Nellie the Elephant (lyrics only)". NIEHS Kids Pages. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Archived from the original on 28 February 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- op de Beeck, Nathalie (31 December 2012). "Q & A with Natalie Merchant". www.publishersweekly.com. PWxyz, LLC. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Edwards, Owen Dudley (2003). British children's fiction in the Second World War. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 318, 350. ISBN 978-0748616510.

- "This scene almost got Sacha Baron Cohen's upcoming film a NC-17 rating". www.aol.com. AOL. 10 July 2020.

- Reproduction from Ars Oratoria, 1482 via Donald M. Liddell, Chessmen (New York, 1937)

- Golombek, Harry (1976). Chess : a history. New York: Putnam. ISBN 978-0399115752.

- "How to Play Chinese Chess : Xiangqi". AncientChess.com. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- "Chang (Elephant) Building". BKK Kids. 9 October 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

Further reading

- Scigliano, Eric (2002). Love, war, and circuses : the age-old relationship between elephants and humans. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0618015832.

- Binney, Ruth (2006). Nature's Ways Lore, Legend, Fact and Fiction. Newton Abbot: F+W Media. ISBN 978-0715333938.

- Ed Cray and Marilyn Eisenberg Herzog (January 1967). "The Absurd Elephant: A Recent Riddle Fad". Western Folklore. 26 (1): 27–36. doi:10.2307/1498485. JSTOR 1498485.—the evolution of the Elephant Riddle that entered U.S. folklore in California in 1963

- Druce, George C. "The Elephant in Medieval Legend and Art". Journal of the Royal Archaeological Institute. (Vol. 76) London, 1919

- Robbins, Louise E. (2002). Elephant slaves and pampered parrots : exotic animals in eighteenth century Paris ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Baltimore [u.a.]: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0801867538.

- Bedini, Silvio A. (1998). The pope's elephant (1. US ed.). Nashville: Sanders. ISBN 978-1879941410.

- ed, Fowler Museum of Cultural History. Doran H. Ross (1992). Elephant : the animal and its ivory in African culture. Los Angeles: University of California. ISBN 978-0930741266.

- Mayor, Adrienne (2000). "CHAPTER 2. Earthquakes and Elephants: Prehistoric Remains in Mediterranean Lands". The First Fossil Hunters Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myth in Greek and Roman Times (New in Paper ; with a new introduction by the author). Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 54–103. ISBN 978-1400838448.

Limited preview on Google Books

- African Folktale as told by Humphrey Harman. "Thunder, Elephant, and Dorobo" (PDF). greatbooks.org. Great Books Foundation.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |

- "Elephants in Culture". Infoqis Publishing, Co. Archived from the original on 19 June 2012. — Elephant-World.com

- "Elephant". Myths, legends, beliefs and traditional stories from Africa. A-Gallery. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008.

- "Elephants on Parade – Medieval and Earlier Manuscripts". British Library. The British Library Board. — Depictions from illuminated manuscripts