Croatian–Slovene Peasant Revolt

The Croatian–Slovene Peasant Revolt (Slovene: hrvaško-slovenski kmečki upor, Croatian: seljačka buna), Gubec's Rebellion (Croatian: Gupčeva buna) or Gubec's peasant uprising of 1573 was a large peasant revolt on territory forming modern-day Croatia and Slovenia. The revolt, sparked by cruel treatment of serfs by Baron Ferenc Tahy, ended after 12 days with the defeat of the rebels and bloody retribution by the nobility.

| Croatian–Slovene Peasant Revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) A non-contemporary representation of the execution of Matija Gubec at the square in front of St. Mark's Church in Zagreb, by Oton Iveković (1912) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Croatian and Slovene peasants |

Croatian, Styrian and Carniolan nobility Uskoks | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Matija Gubec Ilija Gregorić Ivan Pasanec † Nikola Kupinić |

Gašpar Alapić Josip Thurn Ferenc Tahy | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 8,000–12,000[1] peasants | 5,000[1] soldiers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3,000–5,000[2] killed | |||||||

Background

In the late 16th century, the threat of Ottoman incursions strained the economy of the southern flanks of the Holy Roman Empire, and feudal lords continually increased their demands on the peasantry. In Croatian Zagorje, this was compounded by cruel treatment of peasants by Baron Ferenc Tahy and his disputes with neighbouring barons over land, dating back to 1564, which escalated into armed conflicts.[3] When multiple complaints to the emperor went unheard, the peasants conspired to rebel with their peers in the neighbouring provinces of Styria and Carniola and with the lower classes of townspeople.

Revolt

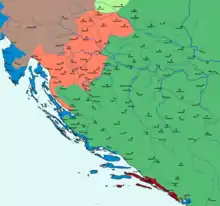

The rebellion broke out simultaneously in large parts of Croatia, Styria, and Carniola on 28 January 1573. The rebels' political program was to replace the nobility with peasant officials answerable directly to the emperor, and to abolish all feudal holdings and obligations to the Roman Catholic Church. A peasant government was formed with Matija Gubec, Ivan Pasanec, and Ivan Mogaić as members.[4] Far-reaching plans were drawn up, including abolition of provincial borders, opening of highways for trade, and self-rule by the peasants.

The captain of the rebels, Ilija Gregorić, planned an extensive military operation to secure victory for the revolt. Each peasant household provided one man for his army, which met with some initial success; their revolutionary goals alarmed the nobility, however, which raised armies in response. The rebels used a network of informers who relayed the information on movements of the opposing units; in turn, spies among the peasants themselves passed the information on the spread of the rebellion to the nobility.[5]

Backlash

On 5 February,[6] Uskok captain and baron Jobst Joseph von Thurn (Croatian: Josip Turn) led an army of 500 Uskoks from Kostanjevica and some German soldiers[7] that defeated a rebel detachment of Nikola Kupinič at Krško (in Lower Styria),[6] which was the first larger rebel defeat.[7] This rapidly weakened the rebellion in Carniola and Styria.[6]

The next day, another rebel force was defeated near Samobor. On 9 February, the decisive Battle of Stubičko polje was fought. Gubec and his 10,000 men resisted fiercely, but after a bloody four-hour battle the baronial army defeated and captured Gubec. The revolt failed.

Retribution was brutal: in addition to the 3,000 peasants who died in the battle, many captives were hanged or maimed. Matija Gubec was publicly tortured and executed on 15 February. Officers Petar Ljubojević, Vuk Suković, and Dane Bolčeta (who were Orthodox), and Juraj Martijanović and Tomo Tortić (Catholics) were all sentenced to life in prison and lost all their property.[8] Mogaić was killed in the final battle, and Pasanec was most probably killed in one of the skirmishes in early February. Gregorić managed to escape, but was captured within weeks, brought to Vienna for interrogation, and executed in Zagreb in 1574.[9]

Legacy

The revolt and torture of Gubec acquired legendary status in Croatia and Slovenia. It has inspired many writers and artists, including the writers Miroslav Krleža and August Šenoa, the poet Anton Aškerc and the sculptors Antun Augustinčić and Stojan Batič. Leading Croatian film director Vatroslav Mimica produced the film about uprising, entitled Anno Domini 1573, in 1975, as well as television series in four parts. Gubec-beg, the first Croatian rock opera (1975), was also inspired by the events.[10]

A museum near Oršić Castle in Gornja Stubica and one in Krško (Slovenia) are dedicated to the revolt.

A reenactment of the Battle of Stubičko polje, held every year since 2008, has since become one of the most popular historical reenactments in Croatia.[11]

Gallery

Large monument in Gornja Stubica

Large monument in Gornja Stubica

(Antun Augustinčić, 1971) Matija Gubec's bust in Zagreb

Matija Gubec's bust in Zagreb

See also

Footnotes

- Čečuk 1960, p. 499.

- Čečuk 1960, p. 500.

- Adamček 1968.

- Adamček 1968, p. 91.

- Antoljak 1973, pp. 95–96.

- Belgrade (Serbia). Vojni muzej Jugoslovenske narodne armije (1968). Fourteen Centuries of Struggle for Freedom. Military Museum. p. xxvi.

- Владимир Ћоровић (1933). Историја Југославије. Народно дело. p. 326.

- Klaić 1928, p. 14.

- "GREGORIĆ, Ilija". Croatian Biographical Lexicon (in Croatian). Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography. 2002. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "Simfonijski puhački orkestar izveo rock-operu Gubec-beg u povodu Dana neovisnosti RH" (in Croatian). 11 October 2017. Archived from the original on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- "Spektakularna 'Bitka kod Stubice' ove godine slavi desetu godišnjicu". nacional.hr (in Croatian). 31 January 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

References

- Adamček, Josip (October 1968). "Prilozi povijesti seljačke bune 1573" (PDF). Radovi Filozofskog fakulteta: Odsjek za povijest (in Croatian) (6): 51–96. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Antoljak, Stjepan (November 1973). "Nekoliko marginalnih opaski o seljačkoj buni 1573. godine" [Marginalia to the 1573 peasant uprising] (PDF). Radovi Zavoda za hrvatsku povijest Filozofskoga fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu (in Croatian). 5 (1): 93–111. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Čečuk, Božidar (March 1960). "Tragom poginulih seljaka u Seljačkoj buni 1573. godine" (PDF). Papers and Proceedings of the Department of Historical Research of the Institute of Historical and Social Research of Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts (in Croatian). Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts. 3: 499–503. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- Klaić, Vjekoslav (1928). Crtice iz Hrvatske prošlosti (in Croatian). Matica hrvatska.