Criticism of the Baháʼí Faith

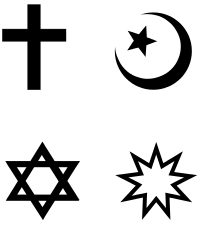

The Baháʼí Faith is a new religious movement[1][2][3][4] that originated in the 19th century and has around 5 million adherents.[5] It grew initially in Iran out of Babism. It's religious foundations rest on many of the teachings of the Bab.[6] From its start there have been controversies and challenges over its teachings and accusations against its leaders. Criticism of the Baháʼí Faith has come primarily from Christians, Muslims, and former Baháʼís. The government of Iran has been especially critical of the Baháʼí Faith, claiming that its Baháʼí population is a political threat.[7]

| Part of a series on |

| Baháʼí Faith |

|---|

|

Criticism falls into a few categories: fault with its teachings, the character of its founders, and ongoing conflicts with its administration.

Baháʼí teachings

Unity of religion

Christians have been known to dismiss the Baháʼí Faith as a syncretic combination of faiths[8] or point to discrepancies between faiths to contradict the idea of unity of religion.[9] The Christian doctrine of atonement is commonly understood to exclude all other religions as a path to God.[10] Regarding the Baháʼí teachings of peace and unity, E.G. Browne argued that while they are admirable, they are, in his opinion, inferior to the simplicity and beauty of the teachings of Christ. He further argued that in the case of "Baha'ism, with its rather vague doctrines as to the nature and destiny of the soul of man, it is a little difficult to see whence the driving force to enforce the ethical maxims can be derived."[11]

Christian apologist Francis J. Beckwith wrote of the Baháʼí teachings:

The fact that the various alleged manifestations of God represented God in contradictory ways implies either that manifestations of God can contradict one another or that God's own nature is contradictory. If manifestations are allowed to contradict one another, then there is no way to separate false manifestations from true ones or to discover if any of them really speak for the true and living God…. If, on the other hand, God's own nature is said to be contradictory, that is, that God is both one God and many gods, that God is both able and not able to have a son, personal and impersonal, etc., then the Bahaʼi concept of God is reduced to meaninglessness.[12]

Baháʼí authors have written in response that the contradictory teachings are either social laws that change from age to age, as part of a progressive revelation, or human error introduced to the more ancient faiths over time.[13][14]

Islamic theology regards Muhammad as the Khatam an-Nabiyyin, the last prophet whom God has sent and Islam as the final religion for all humankind. In this view, it is impossible for either any prophet after Muhammad or any new religion to come into existence, and thus they reject the Baháʼí Faith.[15] Some Muslims claim that the idea of oneness of humanity is not a new principle; they claim that Islam espouses such a principle.[16] Many Islamic scholars reject all prophets after Muhammad, and regard Baháʼís as apostates if they had been Muslims before conversion.[17] Critics also argue that, despite the Baháʼí Faith's claim of unity, there are numerous theological differences between Islam and the Baháʼí Faith,[9] with one critic, Imran Shaykh, arguing that the disparities are evidence to the Baháʼí Faith not being a natural progression of Islam, as is claimed.[18]

Gender equality

While Baháʼí teachings assert that men and women are spiritually equal, author Lil Abdo says that the Baháʼí understanding of sexual equality is different from that of secular feminists. Abdo presented the following list of criticisms of the Baháʼí Faith from a feminist perspective at an annual gathering for Baháʼí studies in 1995:

the ineligibility of women to serve on the Universal House of Justice--this is of particular interest to supporters of women priests within the Christian tradition; the intestacy laws in the Kitab-i-Aqdas; the dowry laws with particular reference to the virginity refund clause; the exemption of menstruating women from obligatory prayers and the implication of menstrual taboo; the exemption of women from pilgrimage; the use of androcentric language and male pronouns in texts; the emphasis on traditional morality and family values...[19]

According to Juan Cole, the law of not allowing women to serve the Universal House of Justice is misinterpreted.[20]

Science

There is some tension over the Baháʼí principle that religion and science should be in harmony. There are statements from the religion's founders of a scientific nature that could be interpreted as contrary to standard science. Prominent among them are references by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá that humans evolved over a long period, but were never animals. Many Baháʼí authors have commented[21] that the intention of the comments were in line with a modern understanding of evolution and that the apparent conflict is an unfortunate semantic mistake. The Baháʼí commentator Salman Oskooi acknowledged that the comments by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá are not in line with current scientific understanding, but that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá should not be regarded as infallible in scientific matters.[22]

Other scientifically controversial ideas from Baháʼu'lláh include that the universe is without beginning or end, that every planet has "creatures", and that copper can turn into gold.

Claims of divinity

Baháʼu'lláh claimed to be a Manifestation of God, which is the Baháʼí term for people like Jesus and Muhammad. William Miller says that the wording of Baháʼu'lláh's Kitáb-i-Aqdas made it difficult to distinguish between the words of the author and the words of God. He further opines that "Baháʼu'lláh felt no such distinction was necessary", as he manifested God as a reflection of a perfect mirror, and that "Baháʼu'lláh claims to be not merely a human Messenger of God, but a Divine Manifestation".[23] This claim of divinity has been criticised by Imran Shaykh who points to this as an example of a discrepancy between faiths.[18]

Denis MacEoin in The Messiah of Shiraz, Brill, 2009, p. 500, note 16 states

The precise nature of Bahāʾ Allāh's claims is difficult to establish. The official modern Bahāʾī doctrine rejects any notion of incarnationism and stresses instead his status as a locus of divine manifestation (maẓhar ilāhī), comparable to a mirror with respect to the sun (see Shoghi Effendi The World Order of Bahāʾuʾllāh, rev. ed. [Wilmette, 1969], pp. 112–114). Nevertheless, it is difficult to avoid the suspicion that he himself made much more radical claims than this in parts of his later writings. The following statements are, I think, explicit enough to serve as examples: 'he who speaks in the most great prison (i.e. Acre) is the Creator of all things and the one who brought all names into being' (letter in Bahāʾ Allāh Āthār-i qalam-i aʿlā, vol. 2 [Tehran, n.d., being a repaginated reprint of a collection of writings originally preceded by the Kitāb al-aqdas, first printed Bombay, 1314/1896], p. 177); 'verily, I am God' (letter in Ishrāq Khāvarī Māʾida, vol. 7, p. 208); 'the essence of the pre-existent (dhāt al-qidām) has appeared' (letter to Ḥājī Muḥammad Ibrāhīm Khalīl Qazvīnī in ibid., vol. 8, p. 113); 'he has been born who begets not nor is begotten' ('Lawḥ-i mīlād-i ism-i aʿẓam' in ibid., vol. 4, p. 344, referring to Qurʾān sūra 112); 'the educator of all beings and their creator has appeared in the garment of humanity, but you were not pleased with that until he was imprisoned in this prison' ('Sūrat al-ḥajj' in Bahāʾ Allāh Āthār-i qalam-i aʿlā, vol. 4 [Tehran, 133 badīʿ/1976–77], p. 203).

Stance on Homosexuality

The exclusion of same-sex marriage among Baháʼís has garnered considerable criticism in the western world, where the Baháʼí teachings on sexuality may appear to be unreasonable, dogmatic, and difficult to apply in Western society.[24] Particularly in the United States, Baháʼís have attempted to reconcile the immutable conservative teachings on sexuality with the otherwise socially progressive teachings of the Faith, but it continues to be a source of controversy.[25] Former Baháʼí William Garlington said the Baháʼí position in America, "can at most be characterized as one of sympathetic disapproval" toward homosexuality.[25]

Historical events

Family of Baháʼu'lláh

Although polygamy is forbidden by Baháʼí law, Baháʼu'lláh himself had three concurrent wives.[26] Under Islamic law a man may have up to four wives, and Baháʼu'lláh wrote in 1873 that a Baháʼí may have two wives. His son ʻAbdu'l-Bahá had one wife and said that having a second wife is conditional upon treating both wives with justice and equality, and was not possible in practice. Baháʼís view the issue as a gradual transition towards monogamy.

Subh-i-Azal

Baháʼís view the Báb (1819-1850) as a predecessor to Baháʼu'lláh, whose claim to revelation established the Baháʼí Faith separate from the Bábí Faith. Before the Báb's death he appointed a caretaker leader named Subh-i-Azal (born Mírzá Yahyá) who was also the half-brother of Baháʼu'lláh. Tensions between Subh-i-Azal and Baháʼu'lláh grew in Baghdad and escalated in Istanbul and Edirne. While in Edirne Subh-i-Azal attempted to murder Baháʼu'lláh with poison, which caused a hard split in 1866 between those Bábís loyal to either Baháʼu'lláh or Subh-i-Azal. When the Ottoman government wished to eliminate the Bábís, they further exiled Baha'u'llah and his followers to Akka, and Subh-i-Azal and his followers to Cyprus, but left several of each in the other's city in an attempt to further stoke conflict. In Akka, a few followers of Baha'u'llah murdered the Azalí Bábís in the city.[27]

Guardianship

The Baháʼí scriptures intend for a line of Guardians to fill an executive role alongside the Universal House of Justice, each Guardian appointed by the preceding one from among the male descendants of Baháʼu'lláh. The first Guardian, Shoghi Effendi, had nobody eligible to appoint and died in 1957 without writing a will[28] and making an appointment. Six years later the first Universal House of Justice was elected and has functioned without a Guardian.[29] In 1960 Mason Remey announced that he should be regarded as the next Guardian, creating a schism in the Baháʼi Faith.[30]

Divisions

The Baháʼí Faith has had several challenges to leadership, notably at the transitions after the passing of Baháʼu'lláh, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, and Shoghi Effendi. Claimants challenging the widely accepted successions of leadership are shunned as covenant-breakers.[31]

Criticism of leadership

Politics

Baháʼís have been accused, particularly by successive Iranian governments, of being agents or spies of Russia, Britain, the Shah, the United States, and as agents of Zionism—each claim being linked to each regime's relevant enemy and justifying anti-Baháʼí actions. The last claim is partially rooted in the presence of the Baháʼí World Centre in northern Israel.[17]

Juan Cole

Juan Cole converted to the Baháʼí Faith in 1972, but later resigned in 1996 after conflicts with members of the administration who perceived him as extreme. Cole went on to critically attack the Baháʼí Faith in several books and articles written from 1998-2000, describing a prominent Baháʼí as "inquisitor" and "bigot", and describing Baháʼí institutions as socially isolating, dictatorial, and controlling, with financial irregularities and sexual deviance.[32] Cole accused the Baháʼí Administration of exaggerating the numbers of believers.[33] Central to Cole's complaints was the Baháʼí review, a process that required Baháʼí authors to gain approval before publishing on the religion.[32]

Soon after his resignation, Cole created an email list and website called H-Bahai, which became a repository of both primary source material and critical analysis on the religion.[34][35][32]

Notes

- MacEoin, Denis (2013-04-01). "Making the invisible visible: introductory books on the Baha'i religion (the Baha'i Faith)". Religion. 43 (2): 164. doi:10.1080/0048721X.2012.705975. ISSN 0048-721X.

- Lesnyanskiy, D. A. (2019). "The History of the Bahai Faith and Features of its Creeds". Научно-издательский центр "Империя": 216–218. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - MacEoin, Denis (1986-01-01). "Emerging from obscurity?". Religion Today. 3 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1080/13537908608580587. ISSN 0267-1700.

- Buck, Christopher (1996). "Review of Rituals in Babism and Bahaism". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 28 (3): 418–422. ISSN 0020-7438.

- See Baháʼí Faith by country for size and scope.

- Hartz 2009, p. 24.

- See Political objections to the Baháʼí Faith

- Christian website referring to Baháʼí Faith as syncretic

- Ankerberg 1999.

- Article from Christian Research Institute

- Miller 1974, p. 163.

- Christian Research Journal, Winter/Spring, 1989, p. 2. Quoted in [9]

- Stockman 1997.

- Smith 2000, p. 274-275.

- Hatcher & Martin 2002, p. 221.

- Basiti, Moradi & Akhoondali 2014, p. 65.

- A.V. 2017.

- Shaykh 2010.

- Abdo 1995.

- Ph.D, Vernon Elvin Johnson (2020-01-16). Baha'is in Exile: An Account of Followers of Baha' U' llah Outside the Mainstream Baha'I Religion. Dorrance Publishing. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-64530-574-3.

- See, for example: Anjam Khursheed (1987). Science and Religion: Towards the Restoration of an Ancient Harmony; Craig Loehle (1990). On Human Origins: A Baháʼí Perspective. Journal of Bahaʼi Studies 2(4); Gary Matthews (1993). The Challenge of Bahaʼu'lláh; Craig Loehle (1994). On the Shoulders of Giants; Eberhard von Kitzing (1997). Is the Baháʼí view of evolution compatible with modern science? Bahaʼi Studies Review 7; Keven Brown (2001). Evolution and Baháʼí Belief: ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Response to Nineteenth-Century Darwinism; Fariborz Alan Davoodi (2001). Human Evolution: Directed? Bahaʼi Library Online; Courosh Mehanian and Stephan Friberg (2003). Religion and Evolution Reconciled: ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Comments on Evolution. Journal of Bahaʼi Studies 13:1-4; Steven Phelps (2008, April–June). Perspective: Crossing the divide between science and religion: a view on evolution. One Country 19(3).

- Salman Oskooi (2009). When Science and Religion Merge:A Modern Case Study.

- Elder, E.E., Miller, W.M. and Miller, W.M. eds., 1961. Al-Kitab Al-Aqdas Or the Most Holy Book (Vol. 38). Psychology Press. p. 20

- Kennedy & Kennedy 1988, p. 3.

- Garlington 2008, pp. 169-171.

- Smith 2000, pp. 273-274.

- Miller 1974, pp. 70-87.

- "Shoghi Effendi's Passing | What Bahá'ís Believe". www.bahai.org. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- Smith 2008, pp. 63–64.

- Johnson 2020, p. 107.

- Miller 1974, pp. 184-185.

- Momen 2007.

- Cole 1998.

- "H-Bahai Website". H-net.org.

- Cole, Juan R. I. (Winter–Summer 2002). "A Report on the H-Bahai Digital Library". Iranian Studies. 35 (1): 191–196. doi:10.1080/00210860208702016. JSTOR 4311442. S2CID 161787329.

References

- A.V. (20 April 2017). "The Economist explains: The Bahai faith". The Economist. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- Abdo, Lil (1995). "Possible Criticisms of the Baha'i Faith from a Feminist Perspective".

- Abdu'l-Bahá (1982) [Composed 1912]. Promulgation of Universal Peace (2nd ed.). Bahai Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-0877431725.

- Abrahamian, E. (1993). Khomeinism: Essays on the Islamic Republic. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08503-9.

- Affolter, Friedrich W. (2005). "The Specter of Ideological Genocide: The Baháʼís of Iran" (PDF). War Crimes, Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. 1 (1): 59–89. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-11-27.

- Afnan, Abul-Qasim (1999), Black Pearls: Servants in the Household of the Bab and Baha'u'llah, Kalimat Press, ISBN 1-890688-03-7

- Ankerberg, John (1999). "A Critical Look at the Baha'i Faith".

- Barrett, David (2001). The New Believers. London, UK: Cassell & Co. ISBN 0-304-35592-5.

- Basiti; Moradi; Akhoondali (2014). Twelve Principles: A Comprehensive Investigation on the Baha'i Teachings (1st ed.). Tehran, Iran: Bahar Afshan Publications. ISBN 978-600-6640-15-0.

- Blomfield, Sara Louisa Ryan (2007). The Chosen Highway. George Ronald Publisher. ISBN 978-0853985099.

- Buck, Christopher (2003). "Islam and Minorities: The Case of the Baháʼís" (PDF). Studies in Contemporary Islam. 5 (1): 83–106. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-08.

- Cole, Juan (1998). "The Baha'i Faith in America as Panopticon, 1963-1997". The Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 37 (2): 234–248. doi:10.2307/1387523. JSTOR 1387523.

- Cole, Juan (2002). "Fundamentalism in the Contemporary U.S. Baha'i Community". Review of Religious Research. 43 (3): 195–217. doi:10.2307/3512329. JSTOR 3512329.

- Effendi, Shoghi (1974). Baháʼí Administration. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-166-3.

- Effendi, Shoghi (1944). God Passes By. Wilmette, Illinois, US: Baháʼí Publishing Trust (published 1979). ISBN 0-87743-020-9.

- Garlington, William (2008). The Baha'i Faith in America (Paperback ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-6234-9.

- Hartz, Paula (2009). World Religions: Baha'i Faith (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 978-1-60413-104-8.

- Johnson, Vernon (2020). Baha'is in Exile: An Account of followers of Baha'u'llah outside the mainstream Baha'i religion. Pittsburg, PA: RoseDog Books. ISBN 978-1-6453-0574-3.

- Kennedy, Sharon H.; Kennedy, Andrew (1988). "Bahá'í Youth and Sexuality A Personal/Professional View" (PDF). The Journal of Bahá’í Studies. 1 (1).

- MacEoin, Denis (2005). "Baháʼísm: Some Uncertainties about its Role as a Globalizing Religion" (PDF). Baháʼí and Globalisation. Denmark: Aarhus University Press: 287–306.

- MacEoin, Denis (1986). "Bahā'ī fundamentalism and the academic study of the Bābī movement". Religion. 16 (1): 57–84. doi:10.1016/0048-721X(86)90006-0.

- McGlinn, Sen (15 September 2009). "Abdu'l-Baha and the African tribe".

- Miller, William (1974). The Baha'i Faith: Its History and Teachings. Pasadena, California, USA: William Carey Library.

- Momen, Moojan (2007). "Marginality and Apostasy in the Baha'i Community". Religion. 37 (3): 187–209. doi:10.1016/j.religion.2007.06.008. S2CID 55630282. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- Munirih Khánum (1987). Munirih Khánum: Memoirs and Letters. Kalimat Press. ISBN 978-0933770515.

- Nabíl-i-Aʻzam (1932), Dawn-Breakers: Nabil's Narrative of the Early Days of the Baha'i Revelation, Baháʼí Publishing Trust, ISBN 978-0877430100

- Schaefer, U.; Towfigh, N.; Gollmer, U. (2000). Making the Crooked Straight: A Contribution to Baháʼí Apologetics. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-443-3. OL 11609763M.

- Shaykh, Imran (July 2010). "Islam vs Bahai Faith - Belief in God".

- Smith, Peter (2000). A Concise Encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith. Oxford, UK: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- Smith, Peter (2008). An Introduction to the Baha'i Faith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86251-6.

- Stockman, Robert (1997). The Baha'i Faith and Syncretism.

- Hatcher; Martin (2002). The Baha'i faith: The emerging global religion. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-1931847063.

- Wilson, Samuel (2018). Bahaism and Its Claims (1st ed.). Books on Demand. ISBN 978-3-73266-137-4.