Controversy over ethnic and linguistic identity in Montenegro

Controversy over ethnic and linguistic identity in Montenegro is an ongoing dispute over the ethnic and linguistic identity of several communities in Montenegro, a multiethnic and multilingual country in Southeastern Europe. There are several points of dispute, some of them related to identity of people who self-identify as ethnic Montenegrins, while some other identity issues are also related to communities of Serbs of Montenegro, Croats of Montenegro, Bosniaks of Montenegro and ethnic Muslims of Montenegro. All of those issues are mutually interconnected and highly politicized.

|

| Part of a series on |

| Montenegro |

|---|

| History |

| Geography |

|

| Politics |

|

| Economy |

| Society |

The central issue is whether self-identified Montenegrins constitute a distinct ethnic group or a subgroup of some other nation, as claimed by Serbs, and also by some Croats. This divide has its historical roots in the first decades of the 20th century, during which the pivotal political issue has been the dilemma between retaining national sovereignty of Montenegro, advocated by supporters of the Petrović-Njegoš dynasty, most notably Greens, i.e. members of the True People's Party, and supporters of integration with the Kingdom of Serbia, and consequently with other South Slavic peoples under the Karađorđević dynasty, advocated by the Whites (gathered around the People's Party). This dispute has been renewed during the dissolution of Yugoslavia and consequent separation of Montenegro which declared its independence from the state union with Serbia in 2006. According to the 2011 census data, 44.98% of people in Montenegro identify as ethnic Montenegrins, while 28.73% declare as ethnic Serbs; 42.88% said they spoke "Serbian" whereas 36.97% declared "Montenegrin" as their native language.

Nationalism in Montenegro

There are generally two variants of nationalism in Montenegro, anti-Serb and pro-Serb.[1]

Historical background

Early modern period

Metropolitan Danilo I (1696–1735) called himself "Duke of the Serb land".[2] Metropolitan Sava called his people, the Montenegrins, the "Serbian nation" (1766).[3] Petar I was the conceiver of a plan to form a new Slavo-Serbian Empire by joining Bay of Kotor, Dubrovnik, Dalmatia, Herzegovina to Montenegro and some of the highland neighbours (1807),[4] he also wrote "The Russian Czar would be recognized as the Tsar of the Serbs and the Metropolitan of Montenegro would be his assistant. The leading role in the restoration of the Serbian Empire belongs to Montenegro."

History

In the late 19th and early 20th century Montenegro's aspirations mirrored that of Serbia — unification and independence of Serb-inhabited lands, most notably due to the desire of the King of Montenegro, Nikola Petrović to rule a larger state, which he presumed would be centered around Serbia, so he strongly promoted a Serbian identity to the Montenegrins.[5] Njegoš (1813–1851), regarded the greatest Montenegrin poet, was a leading Serb figure and instrumental in codifying the Kosovo Myth as the central theme of the Serbian national movement, strongly influenced by Sima Milutinović, Serbian poet and dipomat.[5] The Petrović-Njegoš dynasty tried to take the role as the Serb leader and unifier, but Montenegro's small size and weak economy led to the recognition of the primacy of the Karađorđević dynasty (in Serbia) in this respect.[5] Although some Montenegrin leaders espoused a Serb identity, the Montenegrins were also proud of their state, especially in the Cetinje area, the capital of the Kingdom of Montenegro.[5] The sense of distinct statehood bred an autonomist sentiment in part of the Montenegrin population following the unification with Serbia (and dissolution of Montenegro) in 1918.[5]

Earlier rulers of Montenegrin Petrović-Njegoš dynasty, such as Danilo and Vasilije Petrović presumably considered Montenegrins and Serbs to be two separate groups:

"At one point, our lord asked Novica which are better, Serbs or Montenegrins. Novica replied: "My lord, Serbs are better, they are richer and stronger". Then our lord spat him on his moustache and frowned..." - [6] from the discussion between Danilo l, the ruler of Montenegro and a local.

"Montenegrins were abandoned by their allies, the Serbs, vassals of the Turks" („Crnogorci od svojih saveznika Srba, turskih podanika, bjehu ostavljeni…„) - Vasilije Petrović [7]

This was also the case with Petar l Petrović Njegoš,

"I don't know if any other Serb would ever agree to live in Montenegro, as our kind Milutinović has agreed to" - Petar l, in a letter to Russian diplomat in Dubrovnik, Jeremij Gagich

During the First World War, a controversy over ethnic identity of Montenegrins was sparked by lawyer Ivo Pilar who claimed that during the early medieval times, territory of modern-day Montenegro belonged to hypothetical Red Croatia, developing from that assumption a theory of Croatian ethnic origin of Montenegrins. After the war, that theory was accepted and developed by journalist Savić Marković Štedimlija, who claimed that Montenegrins were in fact a branch of Croatian people.[8]

It has been argued by some that there was no separate Montenegrin nation before 1945. The language, history, religion and culture were considered unquestionably Serbian.[9] Josef Korbel stated, in 1951, that "The Montenegrins proudly called themselves Serbs, and even today it would be difficult to find people of the older generations who would say they are Montenegrin. Only young Communists accept and propagate the theory of a Montenegrin nation."

In contrast to that, others have viewed Montenegrins as a different nation from the Serbs, more in line with the first rulers of Petrović-Njegoš dynasty:

"Moldovans, Vlachs, Bulgars, Serbs, Bosnians, Croats, Montenegrins and Albanians are, to a degree, different nations which possess memories and traditions of their own respective independence.." [10]

"Besides them (Bulgars), there are Serbs, Bosniaks, Montenegrins and other Slavic races..." [11]

[12] AVNOJ recognized five constituent peoples of Yugoslavia: Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians and Montenegrins.[13]

Until the 1990s, most of the Montenegrins defined themselves as both Serbs and Montenegrins.[14] The vast majority of Montenegrins declared themselves as Montenegrins in the 1971–1991 censuses because they were citizens of the Socialist Republic of Montenegro.[14] The 1992 Montenegrin independence referendum saw 96% in favour of Montenegro remaining a part of rump Yugoslavia (FR Yugoslavia – Serbia and Montenegro) which Montenegrin separatists have boycotted.[15] Until 1996, a 'pro-Serbian consensus predominated in Montenegrin politics'.[16]

As Montenegro began to seek independence from Serbia with the Đukanović–Milošević split after the Yugoslav Wars, the Montenegrin nationalist movement emphasized the difference between the Montenegrin and Serbian identities and that the term "Montenegrin" never implied belonging to the wider Serb identity.[14] The people had to make a choice whether they supported Montenegrin independence – the choosing of identity seems to have been based on their stance on independence.[14] Now, those who supported independence redefined the Montenegrin identity as a separate identity (unlike the previous overlapping Montenegrin/Serbian identity espoused by the later rulers from the Montenegrin Petrović-Njegoš dynasty), while those who supported federation with Serbia increasingly insisted on their Serb identity.[14]

According to Srdja Pavlović the Montenegrins preserved the sense of their political and cultural distinctiveness with regard to the other South Slavic groups and continuously reaffirmed it through history. Accordin to him, the notion of Serbdom was understood by Montenegrin to be their belonging to the Eastern Orthodox faith and to Christianity in general, as well as the larger South Slavic context. They incorporated this idea in the building blocks of their national individuality. Because it was understood as the ideology of a constant struggle, this Montenegrin Serbdom did not stand in opostion to a distinct character of Montenegrin national identity. Rather it was used as a tool of pragmatic politics in order to achieve the final goal. Montenegrins used the terms Serbs and Serbdom whenever they referred to South Slavic elements rallied in an anti-Ottoman coalition and around Christian Cross. Whenever they referred to particular elements of their social structure and their political system, they used the term Montenegrin.[17]

The pro-Yugoslav (unionist) side, headed by Momir Bulatović, stressed that Serbians and Montenegrins shared the same ethnicity (as Serbs) and evoked 'the unbreakable unity of Serbia and Montenegro, of one people and one flesh and blood'.[18] Bulatović promoted an exclusive Serb identity for the majority Orthodox population.[18]

Revisionism

There is an ongoing historical revisionism in Montenegro, where Montenegrin identity is promoted with the "Duklja (Doclean) narrative" as founding myth.[19]

Demographic history

| 1909 | 317,856 | ~95% | Principality of Montenegro | According exclusively to language. | |||

| 1921 | 199,227 | 181,989 | 91.3% | Andrijevica, Bar, Kolasin, Niksic, Podgorica and Cetinje counties of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (which are categorized in official statistics as Montenegro) | According to language: Serbo-Croatian | ||

| 1948 | 377,189 | 6,707 | 1.78 | 342,009 | 90.67 | People's Republic of Montenegro (part of FPR Yugoslavia) | First census in Yugoslavia |

| 1953 | 419,873 | 13,864 | 3.3 | 363,686 | 86.61 | People's Republic of Montenegro (part of FPR Yugoslavia) | |

| 1961 | 471,894 | 14,087 | 2.99 | 383,988 | 81.37 | People's Republic of Montenegro (part of FPR Yugoslavia) | |

| 1971 | 529,604 | 39,512 | 7.46 | 355,632 | 67.15 | Socialist Republic of Montenegro (part of SFR Yugoslavia) | |

| 1981 | 584,310 | 19,407 | 3.32 | 400,488 | 68.54 | Socialist Republic of Montenegro (part of SFR Yugoslavia) | |

| 1991 | 615,035 | 54,453 | 9.34 | 380,467 | 61.86 | Socialist Republic of Montenegro (part of SFR Yugoslavia) | Last census in Yugoslavia |

| 2003 | 620,145 | 198,414 | 31.99 | 267,669 | 43.16 | Montenegro as part of Serbia and Montenegro | First census after breakup of Yugoslavia. |

| 2011 | 620,029 | 178,110 | 28.73 | 278,865 | 44.98 | Independent Montenegro | First census as independent state. |

Gallery

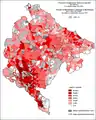

Ethnic structure by municipalities.

Ethnic structure by municipalities. Linguistic structure by settlements.

Linguistic structure by settlements. Linguistic structure by municipalities.

Linguistic structure by municipalities. Serbian language by settlements.

Serbian language by settlements. Montenegrin language by settlements.

Montenegrin language by settlements.

See also

References

- Sabrina P. Ramet (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918-2005. Indiana University Press. pp. 316–. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Džomić 2006.

- Vukcevich, Bosko S. (1990). Diverse forces in Yugoslavia: 1941-1945. p. 379. ISBN 9781556660535.

Sava Petrovich [...] Serbian nation (nacion)

- Banač 1988, p. 274

- Trbovich 2008, p. 68.

- Kotorska Pisma. 1963. p. 113.

- Petrović, Vasilije (1754). The History of Montenegro.

- Slavenko Terzić: Ideological roots of Montenegrin nation and Montenegrin separatism

- Lazarević 2014, p. 428.

- Pictorial history of the Russian War 1854 – 5 – 6: With maps, plans, and wood engravings, 1856.

- Researches in the highlands of Turkey, 1869.

- Josef Korbel (1951). Tito's Communism. Book on Demand. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-5-88379-552-6.

- Trbovich 2008, p. 142.

- Huszka 2013, p. 113.

- Bideleux & Jeffries 2007, p. 477.

- Huszka 2013, pp. 111–112.

- Pavlovic, Srdja (2008). Balkan Anschluss: The Annexation of Montenegro and the Creation of the Common South Slavic State. ISBN 9781557534651.

- Huszka 2013, p. 114.

- Lazarević 2014.

Sources

- Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (2007). "Montenegro: To be or not to be?". The Balkans: A Post-Communist History. Routledge. pp. 471–511. ISBN 978-1-134-58328-7.

- Džomić, Velibor V. (2006). Pravoslavlje u Crnoj Gori [Orthodoxy in Montenegro]. Svetigora. ISBN 9788676600311.

- Huszka, Beata (2013). "The Montenegrin independence movement". Secessionist Movements and Ethnic Conflict: Debate-Framing and Rhetoric in Independence Campaigns. Routledge. pp. 104–132. ISBN 978-1-134-68784-8.

- Lazarević, Dragana (2014). "The Montenegrin Case – Finding a Foundation Myth". Istorija i geografija: susreti i prožimanja [History and geography: meetings and permeations]. Belgrade. pp. 428–443. ISBN 978-86-7005-125-6.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (1999). A history of the Balkans, 1804-1945. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-04585-9.

- Trbovich, Ana S. (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533343-5.

- Pavlovic, Srdja (2008). Balkan Anschluss: The Annexation of Montenegro and the Creation of the Common South Slavic State. ISBN 9781557534651.

Further reading

- Džankić, Jelena (2014). "Reconstructing the Meaning of Being "Montenegrin"". Slavic Review. 73 (2): 347–371. doi:10.5612/slavicreview.73.2.347. hdl:1814/31495.

- Jovanović, Batrić (1989a). Peta kolona antisrpske koalicije : odgovori autorima Etnogenezofobije i drugih pamfleta.

- Jovanović, Batrić (1989b). Crnogorci o sebi: (od vladike Danila do 1941). Sloboda. ISBN 9788642100913.

- Jovanović, Batrić (2003). Rasrbljivanje Crnogoraca: Staljinov i Titov zločin. Srpska školska knj.

- Malešević, Siniša; Uzelac, Gordana (2007). "A Nation‐state without the nation? The trajectories of nation‐formation in Montenegro" (PDF). Nations and Nationalism. 13 (4): 695–716. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8129.2007.00318.x.

- Negrišorac, Ivan (2011). "Истрага предака: Социопатогени чиниоци у процесу формирања црногорске нације". Летопис Матице српске. Novi Sad: Matica srpska.

- Stamatović, Aleksandar (2007). Антисрпство у уџбеницима историје у Црној Гори (in Serbian). Podgorica: Српско народно вијеће. ISBN 978-9940-9009-1-5.

- Troch, Pieter (2008). "The divergence of elite national thought in Montenegro during the interwar period". Tokovi Istorije (1–2): 21–37. ISSN 0354-6497.

- Vukčević, Nikola (1981). Етничко поријекло Црногораца [Ethnic origin of the Montenegrins]. Belgrade.

External links

- "Jedan jezik, a dve gramatike". Novosti.