Combined hormonal contraception

Combined hormonal contraception (CHC), or combined birth control, is a form of hormonal contraception which combines both an estrogen and a progestogen in varying formulations.[1][2]

| Combined hormonal contraception | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background | |

| Type | Hormonal |

| First use |

|

| Failure rates (first year) | |

| Perfect use | 0.3%[1]% |

| Typical use | 9%[1]% |

| Usage | |

| Reversibility | on discontinuation |

| User reminders | ... |

| Advantages and disadvantages | |

| STI protection | ... "No" |

| Periods | ...regular and lighter |

| Weight | No evidence of weight gain[1] |

| Benefits | ... |

The different types available include the pill, the patch and the vaginal ring, which are all widely available,[3] and an injection, which is available in only some countries.[4] They work by mainly suppressing luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and in turn preventing ovulation.[1]

The pill, patch, and vaginal ring are all about 93% effective with typical use.[5] Beneficial health effects include reduced risks of ovarian, endometrial and colorectal cancers. CHC can also provide improved control of some menstrual problems. Adverse effects include a small but higher risk of venous thromboembolism, arterial thromboembolism, breast cancer and cervical cancer.[4][6]

Types

Types of combined hormonal contraception[7] include:

Widely available

- Combined oral contraceptive pill[3]

- Combined contraceptive patch[3]

- Combined contraceptive vaginal ring[3]

Available in only some countries

- Combined injectable contraceptive,[8] which is not available in the USA or UK.[9]

Medical use

Traditionally, to mimic a normal menstrual cycle, CHC is used for 21 consecutive days. For all of these methods (pill, patch, vaginal ring), these 21 days are typically followed by either 7 days of no use (for the pill, patch or vaginal ring) or 7 days of administration of placebo pills (for the pill only). During these 7 days, withdrawal bleeding occurs. For those individuals who do not desire withdrawal bleeding or require bleeding to be suppressed completely, medication regimens can be tailored to the individual with extended periods of use and infrequent hormone-free periods. The efficacy of CHC is the same whether these methods are used continuously or with a 7 day break to allow for withdrawal bleeding.[10]

Mechanism of action

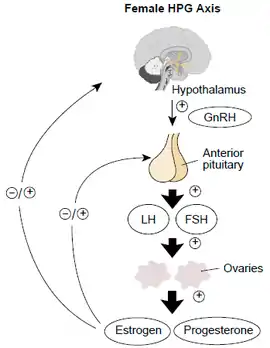

Combined hormonal contraception works by acting on the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis to suppress luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and in turn prevent ovulation. The addition of progesterone contributes to the contraceptive effect by making changes to the cervical mucus, endometrium and tubal motility.[1][11][12]

Effectiveness

The pill, patch and ring have similar effectiveness and this depends largely on the woman using it in the prescribed way. Other factors affecting effectiveness include drug interactions, malabsorption and body weight.[1]

Adverse effects

Although the risk of venous thromboembolism, arterial thromboembolism, breast cancer and cervical cancer in CHC users is small, all CHCs are associated with higher risks of these compared to no use. Given that the vast majority of the studies evaluating these associations have been observational studies, causation between CHC use and these conditions is unable to be determined.[13][14] All CHCs are associated with an increased incidence of venous and arterial thromboembolism. However, those containing higher doses of estrogen are associated with an increase in venous and arterial thromboembolism.[15][16] In addition, some formulations of progesterone, including gestodene, desogestrel, cyproterone acetate and drospirenone, in combination with estrogen, have been associated with higher rates of venous thromboembolism compared to formulations containing a type of progesterone called levonorgestrel.[17]

Other adverse effects include nausea, headaches, breast pain, skin pigmentation, irregular menstrual bleeding, absent periods and irritation from contact lenses. Changes in libido and mood, decline of liver function and raised blood pressure may also occur.[1]

| Type | Route | Medications | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menopausal hormone therapy | Oral | Estradiol alone ≤1 mg/day >1 mg/day | 1.27 (1.16–1.39)* 1.22 (1.09–1.37)* 1.35 (1.18–1.55)* |

| Conjugated estrogens alone ≤0.625 mg/day >0.625 mg/day | 1.49 (1.39–1.60)* 1.40 (1.28–1.53)* 1.71 (1.51–1.93)* | ||

| Estradiol/medroxyprogesterone acetate | 1.44 (1.09–1.89)* | ||

| Estradiol/dydrogesterone ≤1 mg/day E2 >1 mg/day E2 | 1.18 (0.98–1.42) 1.12 (0.90–1.40) 1.34 (0.94–1.90) | ||

| Estradiol/norethisterone ≤1 mg/day E2 >1 mg/day E2 | 1.68 (1.57–1.80)* 1.38 (1.23–1.56)* 1.84 (1.69–2.00)* | ||

| Estradiol/norgestrel or estradiol/drospirenone | 1.42 (1.00–2.03) | ||

| Conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate | 2.10 (1.92–2.31)* | ||

| Conjugated estrogens/norgestrel ≤0.625 mg/day CEEs >0.625 mg/day CEEs | 1.73 (1.57–1.91)* 1.53 (1.36–1.72)* 2.38 (1.99–2.85)* | ||

| Tibolone alone | 1.02 (0.90–1.15) | ||

| Raloxifene alone | 1.49 (1.24–1.79)* | ||

| Transdermal | Estradiol alone ≤50 μg/day >50 μg/day | 0.96 (0.88–1.04) 0.94 (0.85–1.03) 1.05 (0.88–1.24) | |

| Estradiol/progestogen | 0.88 (0.73–1.01) | ||

| Vaginal | Estradiol alone | 0.84 (0.73–0.97) | |

| Conjugated estrogens alone | 1.04 (0.76–1.43) | ||

| Combined birth control | Oral | Ethinylestradiol/norethisterone | 2.56 (2.15–3.06)* |

| Ethinylestradiol/levonorgestrel | 2.38 (2.18–2.59)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/norgestimate | 2.53 (2.17–2.96)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/desogestrel | 4.28 (3.66–5.01)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/gestodene | 3.64 (3.00–4.43)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/drospirenone | 4.12 (3.43–4.96)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/cyproterone acetate | 4.27 (3.57–5.11)* | ||

| Notes: (1) Nested case–control studies (2015, 2019) based on data from the QResearch and Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) databases. (2) Bioidentical progesterone was not included, but is known to be associated with no additional risk relative to estrogen alone. Footnotes: * = Statistically significant (p < 0.01). Sources: See template. | |||

Drug interactions

Liver enzyme inducing drugs

Medications that induce liver enzymes increase the metabolism of oestradiol and progestogens and subsequently may reduce the effectiveness of CHC. The advice on CHC also depends on whether the liver inducing drug is used short term, for less than two months, or long term, for more than two months.[1]

Ulipristal acetate (ellaOne)

Should a woman have taken ulipristal acetate (ellaOne) for emergency contraception, restarting CHC may reduce ellaOne's effectiveness, hence advice is to wait five days before commencing CHC.[1]

Antibiotics

Extra contraceptive precautions are not necessary when using CHC in combination with antibiotics that do not induce liver enzymes, unless the antibiotics cause vomiting and/or diarrhoea.[1]

Antiepileptics

Medications used in the treatment of epilepsy can interact with the combined pill, patch or vaginal ring,[18] resulting in both pregnancy and shift in seizure threshold.[19]

Lamotrigine

Based on a study of 16 women using oral CHC 30 μg ethinyloestradiol/150 μg levonorgestrel and anti-epileptic drug lamotrigine for 6 weeks, it was revealed that the contraceptive effectiveness could be lowered, despite lamotrigine not being an enzyme inducer.[1]

An assessment of risks versus benefits of CHC is recommended in women on lamotrigine who are considering CHC, as the seizure threshold in someone on lamotrigine may be lowered by the oestrogen in CHC. In a similar mechanism, stopping CHC in a woman on lamotrigine can cause lamotrigine toxicity.[1] Long-acting reversible contraception instead may be preferable.[18]

Incorrect usage

If pills are missed or the ring or patch used incorrectly, the chance of pregnancy is increased. In the UK, the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare issue guidance for incorrectly used CHC pills, patches and rings.[1]

Special populations

Following childbirth, the use of CHC depends on factors such as whether the woman is breastfeeding and whether she has other medical conditions including superficial venous thrombosis and dyslipidaemia.[20]

Age

When considering CHC use by age only, use is unrestricted between menarche and age 40, and can be generally used after age 40.[2]

Breastfeeding

CHC should not be used by breastfeeding women in the first six weeks after delivery and are generally not recommended in the first six months after delivery if still breastfeeding. After six months, breastfeeding women may use CHC.[21]

Health benefits

CHCs may reduce the risk of ovarian, endometrial and colorectal cancer.[1]

Other possible benefits include regular and reduced menstrual bleeding, less pain, and control of premenstrual syndrome, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and endometriosis symptoms.[1]

Epidemiology

In the UK, one survey demonstrated that in 2010–2012, more than 33% of women aged 16–44 years had used oral contraception in the previous year and that it was mostly the combined type.[1]

History

CHC has been used worldwide for more than 60 years,[1] with the first clinical trials on oral CHC beginning in 1956.[22]

The combined injectable contraceptive was developed in 1963 and by 1976, two types of these were in use.[23]

The study of CHC vaginal rings began in the early 1970s and the NuvaRing first became available in 2009. In 2003, the contraceptive patch became available, requiring re-application of a new one every week for three weeks, followed by one week without a patch.[22]

See also

References

- "FSRH Clinical Guideline: Combined Hormonal Contraception (January 2019, Amended February 2019) – Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare". www.fsrh.org. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Altshuler, Anna L.; Gaffield, Mary E.; Kiarie, James N. (December 2015). "The WHO's medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use: 20 years of global guidance". Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 27 (6): 451–459. doi:10.1097/GCO.0000000000000212. ISSN 1040-872X. PMC 5703409. PMID 26390246.

- "Combined Hormonal Birth Control: Pill, Patch, and Ring – ACOG". www.acog.org. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- WHO | Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use (PDF) (5th ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2015. p. 111. ISBN 978-92-4-154915-8. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- "Your birth control choices". Reproductive Health Access Project. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- "FSRH Clinical Guideline: Combined Hormonal Contraception (January 2019, Amended February 2019) – Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare". www.fsrh.org. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Commissioner, Office of the (15 June 2019). "Birth Control". FDA.

- Hassan EO and El-Gibaly OM Combination injectable contraceptives for contraception : RHL commentary (last revised: 1 October 2009). The WHO Reproductive Health Library; Geneva: World Health Organization

- Guillebaud, John; MacGregor, Anne (2017). Contraception: Your Questions Answered E-Book (seventh ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-7020-7000-6.

- Wright, Kristen Page; Johnson, Julia V (2008). "Evaluation of extended and continuous use oral contraceptives". Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 4 (5): 905–911. ISSN 1176-6336. PMC 2621397. PMID 19209272.

- "CDC – Combined Hormonal Contraceptives – US SPR – Reproductive Health". www.cdc.gov. 2019-01-16. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- "Combined hormonal contraceptives". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- "Hormonal Contraception and Risk of Breast Cancer". www.acog.org. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- "Oral Contraceptives (Birth Control Pills) and Cancer Risk - National Cancer Institute". www.cancer.gov. 2018-03-01. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- "FSRH Clinical Guideline: Combined Hormonal Contraception (January 2019, Amended February 2019) – Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare". www.fsrh.org. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- WHO | Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use (2015) p.121-132

- "Contraceptive pills and venous thrombosis". www.cochrane.org. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- "Lamotrigine and contraception | Epilepsy Action". www.epilepsy.org.uk. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- Reimers, Arne; Brodtkorb, Eylert; Sabers, Anne (1 May 2015). "Interactions between hormonal contraception and antiepileptic drugs: Clinical and mechanistic considerations". Seizure. Gender Issues in Epilepsy. 28: 66–70. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2015.03.006. ISSN 1059-1311. PMID 25843765.

- WHO Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use (2015) p. 7

- WHO Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use (2015) p. 28

- "Contraception: past, present and future factsheet". FPA. 15 June 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- J. Bringer; B. Hedon (15 September 1995). Fertility and Sterility: A Current Overview. CRC Press. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-1-85070-694-6.