Chinese script styles

In Chinese calligraphy, Chinese characters can be written according to five major styles. These styles are intrinsically linked to the history of Chinese script.

Styles

| English name | Chinese (trad. Hanzi) Japanese (Kanji) Korean (Hanja) Vietnamese (Hán tự) |

Chinese (Hanzi - simplified) | Chinese, Mandarin (Pinyin) | Japanese (Hepburn Romaji) | Korean (Hangul) | Korean (Revised Romanization) | Vietnamese (chữ Quốc ngữ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seal script (Small seal) |

篆書 | 篆书 | Zhuànshū | Tensho | 전서 | Jeonseo | Triện thư |

| Clerical script (Official script) | 隸書 (Jpn: 隷書) |

隶书 | Lìshū | Reisho | 예서 | Yeseo | Lệ thư |

| Semi-cursive script (Running script) |

行書 | 行书 | Xíngshū | Gyōsho | 행서 | Haengseo | Hành thư |

| Cursive script (Sloppy script) | 草書 | 草书 | Cǎoshū | Sōsho | 초서 | Choseo | Thảo thư |

| Regular script (Standard script) | 楷書 | 楷书 | Kǎishū | Kaisho | 해서 | Haeseo | Khải thư |

|

|

|

|

|

When used in decorative ornamentation, such as book covers, movie posters, and wall hangings, characters are often written in ancient variations or simplifications that deviate from the modern standards used in Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese or Korean. Modern variations or simplifications of characters, akin to Chinese Simplified characters or Japanese shinjitai, are occasionally used, especially since some simplified forms derive from cursive script shapes in the first place.

The Japanese syllabaries of katakana and hiragana are used in calligraphy; the katakana were derived from the shapes of regular script characters and hiragana from those of cursive script. In Korea, the post-Korean War period saw the increased use of hangul, the Korean alphabet, in calligraphy.

Seal script

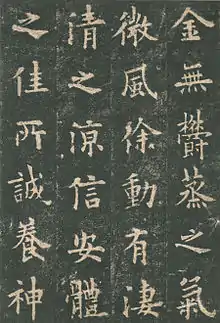

The seal script (often called "small seal" script) is the formal script of the Qín system of writing, which evolved during the Eastern Zhōu dynasty in the state of Qín and was imposed as the standard in areas Qín gradually conquered. Although some modern calligraphers practice the most ancient oracle bone script as well as various other scripts older than seal script found on Zhōu dynasty bronze inscriptions, seal script is the oldest style that continues to be widely practiced.

Today, this style of Chinese writing is used predominantly in seals, hence the English name. Although seals (name chops), which make a signature-like impression, are carved in wood, jade and other materials, the script itself was originally written with brush and ink on bamboo books and other media, just like all other ancient scripts.

Most people today cannot read the seal script, so it is considered an ‘ancient’ script, generally not used outside the fields of calligraphy and carved seals. However, because seals act like legal signatures in the cultures of China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, and because vermillion seal impressions are a fundamental part of the presentation of works of art such as calligraphy and painting, seals and therefore seal script remain ubiquitous.

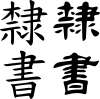

Clerical script

The clerical script (often simply termed lìshū; and sometimes called "official", "draft", or "scribal" script) is popularly thought to have developed in the Hàn dynasty and to have come directly from seal script, but recent archaeological discoveries and scholarship indicate that it instead developed from a roughly executed and rectilinear popular or ‘vulgar’ variant of the seal script as well as from seal script itself, resulting first in a ‘proto-clerical’ version in the Warring States period to Qin dynasty,[1] which then developed into clerical script in the early Western Hàn dynasty, and matured stylistically thereafter.

Clerical script characters are often "flat" in appearance, being wider than the preceding seal script and the modern standard script, both of which tend to be taller than they are wide; some versions of clerical are square, and others are wider. Compared with the preceding seal script, forms are strikingly rectilinear; however, some curvature and some seal script influence often remains. Seal script tended towards uniformity of stroke width, but clerical script gave the brush freer rein, returning to the variations in width seen in early Zhōu brushwork. Most noticeable is the dramatically flared tail of one dominant horizontal or downward-diagonal stroke, especially that to the lower right. This characteristic stroke has famously been called 'silkworm head and wild goose tail' (蠶頭雁尾 cántóu yànwěi)in Chinese) due to its distinctive shape.

The archaic clerical script or ‘proto-clerical’ of the Chinese Warring States period to Qín Dynasty and early Hàn Dynasty can often be difficult to read for a modern East Asian person, but the mature clerical script of the middle to late Hàn dynasty is generally legible. Modern calligraphic works and practical applications (e.g., advertisements) in the clerical script tend to use the mature, late Hàn style, and may also use modernized character structures, resulting in a form as transparent and legible as regular (or standard) script. The clerical script remains common as a typeface used for decorative purposes (for example, in displays), but other than in artistic calligraphy, adverts and signage, it is not commonly written.

Semi-cursive script

The semi-cursive script (also called "running" script, 行書) approximates normal handwriting in which strokes and, more rarely, characters are allowed to run into one another. In writing in the semi-cursive script, the brush leaves the paper less often than in the regular script. Characters appear less angular and instead rounder.

In general, an educated person in China or Japan can read characters written in the semi-cursive script with relative ease, but may have occasional difficulties with certain idiosyncratic shapes.

Cursive script

The cursive script (sometimes called "sloppy script", 草書) is a fully cursive script, with drastic simplifications requiring specialized knowledge; hence it is difficult to read for those unfamiliar with it.

Entire characters may be written without lifting the brush from the paper at all, and characters frequently flow into one another. Strokes are modified or eliminated completely to facilitate smooth writing and to create a beautiful, abstract appearance. Characters are highly rounded and soft in appearance, with a noticeable lack of angular lines. Due to the drastic simplification and ligature involved, this script is not considered particularly legible to the average person, and thus has never achieved widespread use beyond the realm of literati calligraphers.

The cursive script is the source of Japanese hiragana, as well as many modern simplified forms in Simplified Chinese characters and Japanese shinjitai.

Regular script

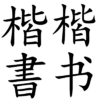

The regular script (often called "standard" script or simply ‘kǎishū’ 楷书) is one of the last major calligraphic styles to develop, emerging between the Chinese Hàn dynasty and Three Kingdoms period, gaining dominance in the Southern and Northern Dynasties, and maturing in the Táng Dynasty. It emerged from a neatly written, early period semi-cursive form of clerical script. As the name suggests, the regular script is "regular", with each of the strokes placed slowly and carefully, the brush lifted from the paper and all the strokes distinct from each other.

The regular script is also the most easily and widely recognized style, as it is the script to which children in East Asian countries and beginners of East Asian languages are first introduced. For learners of calligraphy, the regular script is usually studied first to give students a feel for correct placement and balance, as well as to provide a proper base for the other, more flowing styles.

In the regular script samples to the right, the characters in the left column are in Traditional Chinese while those to the right are in Simplified Chinese.

Edomoji

There is also a large family of native Japanese calligraphic styles known as edomoji, characters created in the Edo period of Japanese history, such as sumōmoji (sumo letters) used to write sumō wrestling posters, kanteiryū, used for kabuki, higemoji, and so on. These styles are typically not taught in Japanese calligraphy schools.

Chinese and Korean people can read edomoji, but the style has a distinct Japanese feel to it. It is therefore commonly used in China and Korea to advertise Japanese restaurants.

Munjado

Munjado is a Korean decorative style of rendering Chinese characters in which brush strokes are replaced with representational paintings that provide commentary on the meaning.[2] The characters thus rendered are traditionally those for the eight Confucian virtues of humility, honor, duty, propriety, trust, loyalty, brotherly love, and filial piety.

Kaō

The kaō is a stylized calligraphic signature. Many Japanese emperors, shōgun, and even modern politicians develop their own kaō.

See also

References

Citations

- Qiu 2000; p.59, 104, 106, 107 & 108

- "Munjado". National Folk Museum of Korea. Archived from the original on 2007-03-13.

Sources

- Generalities

- Qiu Xigui (2000). Chinese writing. Berkeley: The Society for the Study of Early China and The Institute of East Asian Studies. [English translation by Gilbert L. Mattos and Jerry Norman of Wénzìxué Gàiyào 文字學概要, Shangwu, 1988.]

- Ancient characters

- Boltz, William G. (1994). The origin and early development of the Chinese writing system. New Haven, Connecticut: The American Oriental Society.

- Keightley, David (1978). Sources of Shang history: the oracle-bone inscriptions of bronze-age China. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

- Norman, Jerry (1988). Chinese. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chinese Characters. |

- Chinese Calligraphy Script in the book (1997) "Chinese Calligraphy, Abstract Art, Mind Painting" by Ngan Siu-Mui

- History of Chinese writing

- Evolution of Chinese Characters

- Zhongwen.com : a searchable dictionary with information about character formation

- Chinese character etymologies

- Chinese Characters: Explanation of the forms of Chinese Characters; of their ideographic nature. Based on the Shuo Wen, other traditional sources and modern archeological finds.