Century of humiliation

The century of humiliation, also known as the hundred years of national humiliation, is the term used in China to describe the period of intervention and subjugation of the Chinese Empire and the Republic of China by Western powers, Russia and Japan in between 1839 and 1949.[1]

| Century of humiliation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 百年恥辱 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 百年耻辱 | ||||||

| |||||||

The term arose in 1915, in the atmosphere of rising Chinese nationalism opposing the Twenty-One Demands made by the Japanese government and their acceptance by Yuan Shikai, with the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) and Chinese Communist Party both subsequently popularizing the characterization.

History

Chinese nationalists in the 1920s and 1930s dated the Century of Humiliation to the mid-19th century, on the eve of the First Opium War[2] amidst the political unraveling of Qing China that followed.[3]

Defeats by foreign powers cited as part of the Century of Humiliation include:

- Defeat in the First Opium War (1839–1842) by the British

- The unequal treaties (in particular Nanking, Whampoa, Aigun and Shimonoseki)

- Defeat in the Second Opium War (1856–1860) and the sacking of the Old Summer Palace by British and French forces.

- Signed the Treaty of Aigun (1858) and Treaty of Peking (1860) during the Second Opium War, which ceded Outer Manchuria to Russia.

- Partial defeat in the Sino-French War (1884-1885), losing the suzerainty over Vietnam and the influence in Indochina peninsula.

- Defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) by Japan

- The Eight-Nation Alliance invasion to suppress the Boxer uprising (1899–1901) and impose reparations in excess of the government's annual tax revenue.[4]

- British expedition to Tibet (1903–1904)[5]

- The Twenty-One Demands (1915) for loan advantage and local government control by Japan

- Japanese invasion of Manchuria (1931–1932)

- The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945)

In this period, China suffered major internal fragmentation, lost almost all of the wars it fought, and was often forced to give major concessions to the great powers in the subsequent treaties.[6] In many cases, China was forced to pay large amounts of reparations, open up ports for trade, lease or cede territories (such as Outer Manchuria and parts of Outer Northwest China to the Russian Empire, Jiaozhou Bay to Germany, Hong Kong to Great Britain, Zhanjiang to France, and Taiwan and Dalian to Japan) and make various other concessions of sovereignty to foreign "spheres of influence", following military defeats.

Capture of Chusan during the First Opium War in 1841

Capture of Chusan during the First Opium War in 1841 Ruins of the Old Summer Palace, which was looted and destroyed Anglo-French troops during the Second Opium War in 1860

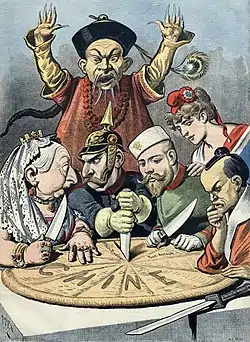

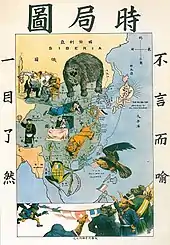

Ruins of the Old Summer Palace, which was looted and destroyed Anglo-French troops during the Second Opium War in 1860 Imperialism 1900: The bear represents Russia, the lion Britain, the frog France, the sun Japan, and the eagle the United States.

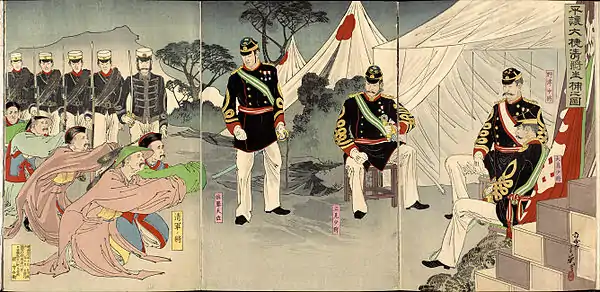

Imperialism 1900: The bear represents Russia, the lion Britain, the frog France, the sun Japan, and the eagle the United States. Chinese generals in Pyongyang surrender to the Japanese during the Sino-Japanese War, October 1894.

Chinese generals in Pyongyang surrender to the Japanese during the Sino-Japanese War, October 1894. U.S. Marines fight Boxers outside Beijing Legation Quarter, 1900. Copy of painting by Sergeant John Clymer.

U.S. Marines fight Boxers outside Beijing Legation Quarter, 1900. Copy of painting by Sergeant John Clymer. American troops in front of the Beijing city walls during the Battle of Peking, 1900

American troops in front of the Beijing city walls during the Battle of Peking, 1900 Soldiers of the Eight-Nation Alliance in the Forbidden City following the defeat of the Boxer Rebellion, 1901.

Soldiers of the Eight-Nation Alliance in the Forbidden City following the defeat of the Boxer Rebellion, 1901. Chinese opium smokers in 1902

Chinese opium smokers in 1902 Casualties of a mass panic during a Japanese air raid in Chongqing (Chungking)

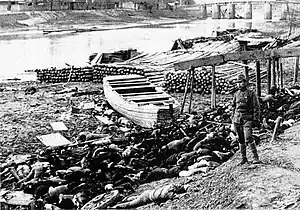

Casualties of a mass panic during a Japanese air raid in Chongqing (Chungking) A mass grave of victims of the Nanjing Massacre on the shore of the Qinhuai River

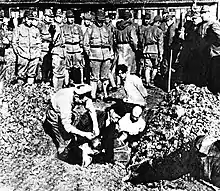

A mass grave of victims of the Nanjing Massacre on the shore of the Qinhuai River Chinese civilians being buried alive by Japanese troops

Chinese civilians being buried alive by Japanese troops

End of humiliation

When or whether the Century has ended has been open to different interpretations. Both Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong declared the end of the Century of Humiliation in the aftermath of World War II, with Chiang promoting his wartime resistance to Japanese rule and China's place among the Big Four in the victorious Allies in 1945, while Mao declared it with the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949.

Extraterritorial jurisdiction was abandoned by the United Kingdom and the United States in 1943. Chiang Kai-shek forced the French to hand over all their concessions back to Chinese control after World War II.

The end of the Century was similarly declared in the repulsion of UN forces in the Korean War, the 1997 reunification with Hong Kong, the 1999 reunification with Macau, and even the hosting of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.[7]

Implications

The usage of the Century of Humiliation in the Chinese Communist Party's historiography and modern Chinese nationalism, with its focus on the "sovereignty and integrity of [Chinese] territory",[8] has been invoked in incidents such as the US bombing of the Chinese Belgrade embassy, the Hainan Island incident, and protests for Tibetan independence along the 2008 Beijing Olympics torch relay.[9] Some analysts have pointed to its use in deflecting foreign criticism of human rights abuses in China and domestic attention from issues of corruption, while bolstering its territorial claims and general economic and political rise.[7][10][11]

Commentary and criticism

Jane E. Elliott criticized the allegation that China refused to modernize or was unable to defeat Western armies as simplistic, noting that China embarked on a massive military modernization in the late 1800s after several defeats, buying weapons from Western countries and manufacturing their own at arsenals, such as the Hanyang Arsenal during the Boxer Rebellion. In addition, Elliott questioned the claim that while Chinese society was traumatized by the Western victories, as many Chinese peasants (90% of the population at that time) living outside the concessions continued about their daily lives, uninterrupted and without any feeling of "humiliation".[12]

Historians have judged the Qing dynasty's vulnerability and weakness to foreign imperialism in the 19th century to be based mainly on its maritime naval weakness while it achieved military success against Westerners on land, the historian Edward L. Dreyer said that "China's nineteenth-century humiliations were strongly related to her weakness and failure at sea. At the start of the First Opium War, China had no unified navy and not a sense of how vulnerable she was to attack from the sea. British navy forces sailed and steamed wherever they wanted to go. In the Arrow War (1856–60), the Chinese had no way to prevent the Anglo-French navy expedition of 1860 from sailing into the Gulf of Zhili and landing as near as possible to Beijing. Meanwhile, new but not exactly modern Chinese armies suppressed the midcentury rebellions, bluffed Russia into a peaceful settlement of disputed frontiers in Central Asia, and defeated the French forces on land in the Sino-French War (1884–85). But the defeat at sea, and the resulting threat to steamship traffic to Taiwan, forced China to conclude peace on unfavorable terms."[13][14]

See also

| Library resources about Century of humiliation |

References

- Adcock Kaufman, Alison (2010). "The "Century of Humiliation," Then and Now: Chinese Perceptions of the International Order". Pacific Focus. 25 (1): 1–33. doi:10.1111/j.1976-5118.2010.01039.x.

- Gries (2004), p. 43-49.

- Chang, Maria Hsia (2001). Return of the dragon: China'z wounded nationalism. Westview Press. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-8133-3856-9.

- Gries, Peter Hays (2004). China's New Nationalism: Pride, Politics, and Diplomacy. University of California Press. pp. 43–49. ISBN 978-0-520-93194-7.

- "China Seizes on a Dark Chapter for Tibet", by Edward Wong, The New York Times, August 9, 2010 (August 10, 2010 p. A6 of NY ed.). Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- Nike, Lan (2003-11-20). "Poisoned path to openness". Shanghai Star. Archived from the original on 2010-03-23. Retrieved 2010-08-14.

- Kilpatrick, Ryan (20 October 2011). "National Humiliation in China". e-International Relations. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- W A Callahan. "National Insecurities: Humiliation, Salvation and Chinese Nationalism" (PDF). Alternatives. 20 (2004): 199.

- Jayshree Bajoria (April 23, 2008). "Nationalism in China". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 2009-10-14. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- "Narratives Of Humiliation: Chinese And Japanese Strategic Culture – Analysis". Eurasia Review. International Relations and Security Network. 23 April 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Callahan, William (15 August 2008). "China: The Pessoptimist Nation". The China Beat. Archived from the original on 2013-02-17. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Jane E. Elliott (2002). Some did it for civilisation, some did it for their country: a revised view of the boxer war. Chinese University Press. p. 143. ISBN 962-996-066-4. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- PO, Chung-yam (28 June 2013). Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: The Great Qing and the Maritime World in the Long Eighteenth Century (PDF) (Thesis). Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg. p. 11.

- Edward L. Dreyer, Zheng He: China and the Ocean in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433 (New York: Pearson Education Inc., 2007), p. 180