Celia en el colegio

Celia en el colegio ("Celia at the school" or "Celia at school") is the second in the series of Celia novels by Elena Fortún, first published in 1932 according to records. The books told the stories of a little girl named Celia living in Spain during the 1930s. In this second book, Celia was sent to a convent, for her parents found her a handful, and facing numerous financial problems at home, they had trouble looking after Celia and keeping her out of mischief. The books were largely popular in the years following their publication, and were enjoyed by both children and adults. Celia's many adventures and misadventures, as well as her mischievous character appealed to children, while at the same time, older readers were able to pick up references to a changing and growing nation hidden behind Celia's childlike fantasy world. Most prints of the first books featured a large variety of black and white illustrations by Molina Gallent, some of which were later featured in the opening credits of the TV-series from Televisión Española. Other prints and re-issues featured illustrations from other artists such as Asun Balzola.

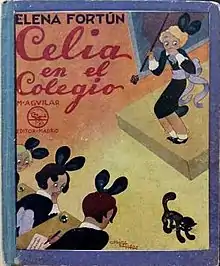

Cover of the first edition of Celia en el colegio, 1932 | |

| Author | Elena Fortún |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Molina Gallent |

| Country | |

| Language | Spanish |

| Series | Celia |

| Genre | Children's novel |

| Publisher | M. Aguilar (1932) Alianza Editorial (2000) |

Publication date | 1932; reprints in 1973, 1980, 1992, 1993 and 2000 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 270 pp |

| ISBN | 84-206-3574-X |

| Preceded by | Celia, lo que dice (1929) |

| Followed by | Celia novelista (1934) |

In 1992, Spanish film director José Luis Borau adapted the series into a six-episode TV series simply entitled Celia.[1] In it, child actress Cristina Cruz Mínguez played the title role of Celia, while Ana Duato (Médico de familia, 1995) and Pedro Díez del Corral played her parents. The series, like the books, found great success originally, but eventually that success faded and today the series is not very well known. "En el colegio" was the title of the fourth episode in the series and the first to be adapted from the second book, Celia en el colegio.

Plot summary

A sequel to Celia, lo que dice (1929), the story narrates Celia's adventures following her father's decision to give in to her mother's wishes of sending their daughter to a convent school for girls. At the school, Celia has many difficulties adapting to the strict rules of the nuns and is often reprimanded by Madre Loreto, whom Celia describes as "very strict and scolds much". During her first days there, Celia is convinced that her father is not at all happy with the change and that he greatly misses his little girl, thus Celia tries to get herself expelled from the school by trying to make the nuns believe she suffers from a sleepwalking problem. Celia is unsuccessful, but she soon learns that though her father misses her, he is willing to allow her to stay at the school, which is good for Celia, who actually enjoys her new home. Celia is the favorite among many of her classmates, but she does have many quarrels with a few other girls who find her behaviour disruptive and inappropriate. Madre Isolina, an English nun Celia describes as "very intelligent and understanding" is Celia's favorite nun at the school because she sometimes helps her out of mischief. Celia tries desperately to be good, she even wishes to become a saint. The priest, Don Restituto, tries to guide Celia, but when the girl starts creating more trouble than usual in her attempt to become a saint, or at least a martyr, he gives up on her and forbids her from being either. Following the end of the term, the other girls leave the convent, but Celia is left there with the nuns since her parents have left the country hoping to find a better job elsewhere and earn money to stabilize themselves economically. Doña Benita, the old lady that had looked after the girl for some time before, comes to the school and takes Celia with her for some time. During those days, Celia and the old woman visit a circus, and from there Celia imagines all sorts of tales following her imaginary escape with the gypsies (tales she narrates in Celia, novelista). In the summer, an elderly woman, Doña Remedios, who is soon mocked and renamed Doña Merlucines by Celia and some of the nuns and workers at the school, arrives and she and Celia become fast enemies. Doña Remedios, who is very kind to Celia at first, is soon irritated by the girl's wild ways and wishes she had more discipline. After many quarrels between the two, Celia gets her revenge by filling the sleeping Doña Remedios' bed with cockroaches. Another schooling term begins and Celia's popularity with the other girl students begins to largely decrease. One day, an angry Tío Rodrigo, Celia's uncle, arrives at the school and demands to be allowed to take his niece away with him to her parents who currently reside in Paris.

The book is told in first-person narrative from Celia's perspective, following a brief introduction in third person from the author's.

Adaptations

Celia en el colegio was adapted as part of Televisión Española's 1992 TV-series directed by José Luis Borau, Celia.[2] The series was a faithful adaptation of many events from the book and it often relied on very similar, if not exact, dialogue. The adapting of Celia en el colegio spanned three episodes: IV. "En el colegio", V. "Ni santa, ni mártir" and VI. "¡Hasta la vista!". Many scenes were removed and absent from the series; one example of this is a part in the novel involving Celia being punished to spend some time up in Madre Florinda's chamber, when Celia, believing the nun to have died gives her belongings to a group of homeless boys and girls. Though the entire part was not touched in the series, the character of Madre Florinda, who can be seen supported by a crutch, was included briefly in the series, if only with a few minor appearances as an extra and just one single line.

Only five of the nuns were referred to by name in the series: Madre Loreto, Madre Bibiana, Madre Corazón, Madre Isolina and the Madre Superiora (the Mother Superior), all of whom appeared in the novel. Certain scenes and incidents from the novel involving the nuns were "traded" around. For example, in the novel, Madre Mercedes is the one responsible for teaching sewing to the girls, while in the series, it was Madre Bibiana who had that task and whom failed at teaching Celia how to sew properly. Another example, in the novel, Madre Consuelo had the ingenious idea of having the girls learn only the answers to the questions they would each be asked in the final examination given by the Madre Superiora, which turned out a complete disaster. In the series however, it was Madre Loreto who had the idea and who was embarrassed by Celia's explaining of the situation. The same with Celia's classmates; only Elguibia, whom differenced from the others due to her slight case of mental retardation, was given a consistent name. The other girl actresses played Celia's friends from the novel inconsistently and were never given real names, at least they were not mentioned.

Other events were altered from the novel in order to give the series a more dramatic appeal. For example, in the novel, Celia does not have a good time during the end-of-the-year plays as she is excluded from participating. However, in the series Celia does have a part in the play; shortly before her performance, Doña Benita feels the need to tell Celia the truth about how her parents had closed down their house in Madrid. How they, together with Celia's brother "Cuchifritín" would leave "for China" and how she would spend the summer with the nuns instead of going to the beach with her parents. Celia, heartbroken with the news, cleverly alters her rhyming lines in the play in order to announce to the entire audience how her parents were leaving for China and leaving her behind. Then, Celia grabs the box of chocolates her father had brought for her and runs in tears to the school's vegetable gardens where she hides and cries telling Culiculá, her pet stork, about all her sorrows. Later in the series, it is Celia's father, rather than Doña Benita, who comes to take her to a small circus visiting the town. When returning home, Celia's father presents her with a small gift, a writing book in which he encourages her to write down all sorts of stories. He leaves her again under the care of Madre Loreto, and the man is startled and disappointed that Celia would walk away so happily without even saying goodbye. Celia turns around, her face flooded in tears, and tells her father that she wants to leave with him and be reunited with her family. Her father tells her that it cannot be, and the girl answers by saying that she will become a performer and travel to China, where she is convinced her parents are going, and the two part feeling very sad. Madre Loreto then tucks Celia in her bed and wishes her good night. Celia pulls out her book and begins writing a story about how she ran away with the gypsies hoping to find her parents on their way to China. Celia's story is told visually in the series, and when she, together with Culiculá the stork, catch up with her gypsy friend Coralinda and her travelling wagon, she convinces the gypsy girl's father to allow her to travel with them. In the back of the wagon, Celia asks Coralinda whether they are travelling to Pekin in China. Being answered in the affirmative, Celia replies, "Es que tengo que encontrar a mis papás", ("It's just that I have to find my parents"), where the series ends, left incomplete. Recurring tracks from the series' original soundtrack were also added to emphasize the dramatic seriousness of Celia's situation. In the novels, these events were not nearly as dramatic, and Celia had an easier time dealing with her parents leaving her behind.

References

External links

- Elena Fortún: Su vida, su obra - Website dedicated to author Elena Fortún featuring her full biography. (Spanish)

- Celia at IMDb