Cave wolf

The cave wolf (Canis lupus spelaeus) is an extinct subspecies of wolf that lived during the Late Pleistocene Ice Age. It inhabited what is now modern-day western Europe. The Don wolf (C. l. brevis) from eastern Europe is regarded as a taxonomic synonym, which indicates that one subspecies once lived across Europe.

| Cave wolf Temporal range: Late Pleistocene - early Holocene | |

|---|---|

| |

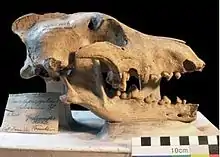

| The Goldfuss holotype,[1] Berlin's Natural History Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | †C. l. spelaeus |

| Trinomial name | |

| Canis lupus spelaeus Goldfuss, 1823[2] | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

|

C. l. brevis (Kuzmina, 1994)[4] | |

Taxonomy

The cave wolf was first described by Georg August Goldfuss in 1823 based on a wolf pup skull found in the Zoolithen Cave located at Gailenreuth, Bavaria, Germany.[2] In the early to middle Late Pleistocene, these large wolves existed all over Europe.[5] They have not been studied in any degree of depth,[5] and their relationship to modern wolves has not been clarified using DNA. All of the top predators in Europe commenced going extinct with the loss of the pleistocene megafauna when conditions became colder during the peak of the Last Glacial Maximum around 23,000 years ago. The last cave wolves used the side branches of the main caves to protect their pups from the cold climate.[6] During this time the cave wolf was replaced by a smaller wolf-type, which then disappeared along with the reindeer, to finally be replaced by the Holocene warm-period European wolf Canis lupus lupus.[5]

In 2009, a study of the fossil remains of Paleolithic dogs and Pleistocene wolves found that five wolf specimens from Trou Baileux, Belgium, Trou des Nutons, Belgium, Mezine, Ukraine, and Yakutia, Siberia had a greater snout width than recent wolves. A similar trend was discovered in the North American fossil East Beringian wolf.[7]

In Hungary in 1969, a tooth (the premolar of the Maxilla) was found which dated to the Middle Pleistocene, and was assessed as being midway between that of Canis mosbachensis and Canis lupus spelaeus, but leaning towards C.l. spelaeus. [8]

Description

Cave wolf populations are known from three caves separated by a few kilometers from each other that are located on the Franconia Karst along the Wiesent and Ahorn River vallies in the Upper Franconia region of the state of Bavaria, Germany. Sophie's Cave sits on the northwest slope of the Ailsbach Valley near Rabenstein Castle in the Ahorntal municipality. Große Teufels Cave (Big Devil's Cave) and the Zoolithen Cave are located nearby.[9] They are also known from Hermann's Cave in the village of Rübeland near the town of Wernigerode, in the district of Harz, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany.[10] Its bone proportions are close to those of the Canadian Arctic-boreal mountain-adapted timber wolf and a little larger than those of the modern European wolf. Some postcranial bones have similarly large proportions to those from the Sophie's and Große Teufels Caves,[9] where the bone sizes are closer to those of Scandinavian Arctic and Canadian Columbian wolf subspecies than to those of the smaller European wolves. Bone sizes are one-eighth larger than European wolves, and this wolf was a specialized Late Pleistocene wolf ecomorph.[6]

Adaptation

_fig._19_colorized.png.webp)

Their dens have been identified, with the Zoolithen Cave supporting a large population and has yielded more than 380 bones as well as several skulls (including a holotype). Sophie's Cave has demonstrated the first "Early Late Pleistocene wolf den", with intensive faecal places and the first European record of half-digested cave bear bones found within the faecal areas in the cave. It demonstrates that wolves seem not to have used this cave as a cub-raising den, but that they were cave dwellers that fed on cave bear carcasses, similar to but less so than cave hyenas, but more so than cave lions. The abundant faeces seem to play a role in the "orientation" for trail tracking, similar to modern wolves, and less as den marking. The high abundance in a limited area of the Bear's Passage of the cave might be the result of periodical short-term den use of smaller cave areas. Wolves were scavenging on the bears that hibernated and died there, and therefore a simultaneous use as both a wolf and a cave bear den cannot be expected. Remains of a skeleton of at least one high adult wolf also might have been the result of a battle within the cave with the bears, the same as in the lion taphonomic record.[5]

The ecology of the early to middle Late Pleistocene wolves on the mammoth steppe and the boreal forests is not known, nor is whether they used caves as dens.[5]

Don wolf

The Don wolf (Canis lupus brevis) is the name designated to the fossil remains of wolves that were found at the Kostenki I Late Pleistocene site by the Don River at Kostyonki, Voronezh Oblast, Russia and reported in 1994. Based on the size of its dental rows, the Don wolf was bigger than modern wolves from the tundra or the Middle Russian taiga. The length of its P4 was longer than the row of its molars M1-M2, which is different to the Late Pleistocene wolves from the Caucasus or the Ural Mountains. Its main characteristic was its shorter legs, due to shorter humerus, radius, metacarpals, tibia, and metatarsals.[4] In 2009, a study compared the skull of one of these wolves to those found in Western Europe, and proposed that C. l. brevis of eastern Europe and C. l. spelaeus of western Europe are synonyms for the same subspecies. These were both comparable to the remains of a 16,000 YBP wolf skull found on the Taimyr peninsula in far northern Siberia.[3]

Relationship with the dog

Mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) passes along the maternal line and can date back thousands of years.[11] Therefore, phylogenetic analysis of mDNA sequences within a species provides a history of maternal lineages that can be represented as a phylogenetic tree.[12][13]

In 2013, a study analysed the complete and partial mitochondrial genome sequences of 18 fossil canids dated from 1,000 to 36,000 YBP from the Old and New Worlds, and compared these with the complete mitochondrial genome sequences from modern wolves and dogs. Phylogenetic analysis showed that modern dog mDNA haplotypes resolve into four monophyletic clades with strong statistical support, and these have been designated by researchers as clades A-D.[14][15][16] Based on the specimens used in this study, clade A included 64% of the dogs sampled and these were sister to a 14,500 YBP wolf sequence from the Kessleroch cave near Thayngen in the canton of Schaffhausen, Switzerland, with a most recent common ancestor estimated to 32,100 YBP. This group of dogs matched three fossil pre-Columbian New World dogs dated between 1,000 and 8,500 YBP, which supported the hypothesis that pre-Columbian dogs in the New World share ancestry with modern dogs and that they likely arrived with the first humans to the New World. Clade B included 22% of the dog sequences and was related to modern wolves from Sweden and the Ukraine, with a common recent ancestor estimated to 9,200 YBP. However, this relationship might represent mitochondrial genome introgression from wolves because dogs were domesticated by this time.

Clade C included 12% of the dogs sampled and these were sister to two ancient dogs from the Bonn-Oberkassel cave (14,700 YBP) and the Kartstein cave (12,500 YBP) near Mechernich in Germany, with a common recent ancestor estimated to 16,000–24,000 YBP. Clade D contained sequences from 2 Scandinavian breeds (Jamthund, Norwegian Elkhound) and were sister to another 14,500 YBP wolf sequence also from the Kesserloch cave, with a common recent ancestor estimated to 18,300 YBP. Its branch is phylogenetically rooted in the same sequence as the "Altai dog" (not a direct ancestor). The data from this study indicated a European origin for dogs that was estimated at 18,800–32,100 years ago based on the genetic relationship of 78% of the sampled dogs with ancient canid specimens found in Europe.[17][14] The data supports the hypothesis that dog domestication preceded the emergence of agriculture[15] and was initiated close to the Last Glacial Maximum when hunter-gatherers preyed on megafauna.[14][18]

The study found that three ancient Belgium canids (the 36,000 YBP "Goyet dog" cataloged as Canis species, along with Belgium 30,000 YBP and 26,000 years YBP cataloged as Canis lupus) formed an ancient clade that was the most divergent group. The study found that the skulls of the "Goyet dog" and the "Altai dog" had some dog-like characteristics and proposed that the may have represented an aborted domestication episode. If so, there may have been originally more than one ancient domestication event for dogs[14] as there was for domestic pigs.[19]

One theory is that domestication occurred during one of the five cold Heinrich events that occurred after the arrival of humans in West Europe 37 000, 29 000, 23 000, 16 500 and 12 000 YBP. The theory is that the extreme cold during one of these events caused humans to either shift their location, adapt through a breakdown in their culture and change of their beliefs, or adopt innovative approaches. The adoption of the large wolf/dog was an adaptation to this hostile environment.[20]

References

- Kempe, Stephan; Döppes, Doris (2009). "Cave Bear, Cave Lion and Cave Hyena Skulls from the Public Collection at the Humboldt Museum in Berlin". Acta Carsologica. 38 (2–3). doi:10.3986/ac.v38i2-3.126.

- Goldfuss, G. A. (1823). "5-Ueber den Hölenwolf (Canis spelaeus) (About the Cave wolf)". Osteologische Beiträge zur Kenntniss verschiedener Säugethiere der Vorwelt (Osteological contributions to different knowledge Beast of the ancients). 3. Nova Acta Physico-Medica Academiea Caesarae Leopoldino-Carolinae Naturae Curiosorum. pp. 451–455.

- Baryshnikov, Gennady F.; Mol, Dick; Tikhonov, Alexei N (2009). "Finding of the Late Pleistocene carnivores in Taimyr Peninsula (Russia, Siberia) with paleoecological context". Russian Journal of Theriology. 8 (2): 107–113. doi:10.15298/rusjtheriol.08.2.04. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- Kuzmina, I. E.; Sablin, M. V. (1994). "Wolf Canis lupus L. from the Late Paleolithic sites Kostenki on the Don River". Trudy Zoologicheskogo Instituta (256): 44–58. In Russian - see the last page for the summary in English

- Diedrich, C. G. (2013). "Extinctions of Late Ice Age Cave Bears as a Result of Climate/Habitat Change and Large Carnivore Lion/Hyena/Wolf Predation Stress in Europe". ISRN Zoology. 2013: 1–25. doi:10.1155/2013/138319.

- Diedrich 2015, pp. 137

- Germonpré, M.; Sablin, M. V.; Stevens, R. E.; Hedges, R. E. M.; Hofreiter, M.; Stiller, M.; Després, V. R. (2009). "Fossil dogs and wolves from Palaeolithic sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: Osteometry, ancient DNA and stable isotopes". Journal of Archaeological Science. 36 (2): 473–490. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.09.033.

- Jánossy, Dénes (2012). "Vertebrate faunas of the Middle Pleistocene of Hungary". Pleistocene Vertebrate Faunas of Hungary. Elsevier Science. p. 102. ISBN 978-0444556356.

- Diedrich 2015, pp. 96–99

- Diedrich 2017, pp. 108–118

- Arora, Devender; Singh, Ajeet; Sharma, Vikrant; Bhaduria, Harvendra Singh; Patel, Ram Bahadur (2015). "Hgs Db: Haplogroups Database to understand migration and molecular risk assessment". Bioinformation. 11 (6): 272–5. doi:10.6026/97320630011272. PMC 4512000. PMID 26229286.

- Avise, J. C. (1994). Molecular Markers, Natural History, and Evolution. Chapman & Hall. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0-412-03781-8.

- Robert K. Wayne, Jennifer A. Leonard, Carles Vila (2006). "Chapter 19:Genetic Analysis of Dog Domestication". In Melinda A. Zeder (ed.). Documenting Domestication:New Genetic and Archaeological Paradigms. University of California Press. pp. 279–295. ISBN 978-0-520-24638-6.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Thalmann, O; Shapiro, B; Cui, P; Schuenemann, V. J; Sawyer, S. K; Greenfield, D. L; Germonpre, M. B; Sablin, M. V; Lopez-Giraldez, F; Domingo-Roura, X; Napierala, H; Uerpmann, H.-P; Loponte, D. M; Acosta, A. A; Giemsch, L; Schmitz, R. W; Worthington, B; Buikstra, J. E; Druzhkova, A; Graphodatsky, A. S; Ovodov, N. D; Wahlberg, N; Freedman, A. H; Schweizer, R. M; Koepfli, K.- P; Leonard, J. A; Meyer, M; Krause, J; Paabo, S; et al. (2013). "Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Ancient Canids Suggest a European Origin of Domestic Dogs". Science. 342 (6160): 871–4. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..871T. doi:10.1126/science.1243650. PMID 24233726.

- Vila, C. (1997). "Multiple and ancient origins of the domestic dog". Science. 276 (5319): 1687–9. doi:10.1126/science.276.5319.1687. PMID 9180076.

- Bjornerfeldt, S (2006). "Relaxation of selective constraint on dog mitochondrial DNA followed domestication". Genome Research. 16 (8): 990–994. doi:10.1101/gr.5117706. PMC 1524871. PMID 16809672.

- Miklosi, Adam (2018). "1-Evolution & Ecology". The Dog: A Natural History. Princeton University Press. pp. 13–39. ISBN 978-0-691-17693-2.

- Shipman, P. (2015). The Invaders:How humans and their dogs drove Neanderthals to extinction. Harvard University Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780674736764.

- Frantz, L. (2015). "Evidence of long-term gene flow and selection during domestication from analyses of Eurasian wild and domestic pig genomes". Nature Genetics. 47 (10): 1141–1148. doi:10.1038/ng.3394. PMID 26323058.

- Schnitzler, Annick; Patou-Mathis, Marylène (2017). "Wolf (Canis lupus Linnaeus, 1758) domestication: Why did it occur so late and at such high latitude? A hypothesis". Anthropozoologica. 52 (2): 149. doi:10.5252/az2017n2a1.

Bibliography

- Diedrich, Cajus G. (2015). Famous Planet Earth Caves: Sophie's Cave (Germany) - A Late Pleistocene Cave Bear Den. Famous Planet Earth Caves. 1. Bentham Books. ISBN 978-1-68108-001-7. ISSN 2405-7215. ebook - eISBN 978-1-68108-000-0

- Diedrich, Cajus G. (2017). Famous Planet Earth Caves: Hermann's Cave (Germany) – A Late Pleistocene Cave Bear Den. Famous Planet Earth Caves. Famous Planet Earth Caves Volume 2. 2. Bentham Books. doi:10.2174/97816810853021170201. ISBN 978-1-68108-531-9. ISSN 2405-7215. ebook - eISBN 978-1-68108-530-2