Capital punishment in Florida

Capital punishment is a legal penalty in the U.S. state of Florida.

Since 1976, the state has executed 99 convicted murderers, all at Florida State Prison.[1] As of November 7, 2020, 339 offenders are awaiting execution.[2]

History

Florida performed its last pre-Furman execution in 1964 (Sie Dawson). After the Supreme Court of the United States struck down all states' death penalty procedures in the Furman v. Georgia ruling, essentially ruling the imposition of the death penalty at the same time as a guilty verdict unconstitutional, Florida was the first state to draft a newly written statute on August 12, 1972.[3]

Florida performed the first judicial execution after the Supreme Court, in the 1976 case Gregg v. Georgia, permitted the death penalty once more. John Arthur Spenkelink was electrocuted on May 25, 1979.[4]

On January 24, 1989, it executed notorious serial killer Ted Bundy.

The method of execution switched to lethal injection after the controversial electrocution of Allen Lee Davis in 1999.

On May 23, 2019, it executed serial rapist and murderer Bobby Joe Long after he had been put on death row in 1984.

On August 22, 2019, it executed serial killer Gary Ray Bowles.

Capital crimes

In Florida, murder can be punished by death if it involves one of the following aggravating factors:[5]

- It was committed by a person previously convicted of a felony, under sentence of imprisonment, placed on community control, or on felony probation.

- The defendant was previously convicted of another capital felony or of a felony involving the use or threat of violence to the person.

- The defendant knowingly created a great risk of death to many persons.

- It was committed while the defendant was engaged, or was an accomplice, in the commission of, or an attempt to commit a specified felony (such as aggravated child abuse, arson, kidnapping, placing or discharging of a destructive device or bomb).

- It was committed for the purpose of avoiding or preventing a lawful arrest or effecting an escape from custody.

- It was committed for pecuniary gain.

- It was committed to disrupt or hinder the lawful exercise of any governmental function or the enforcement of laws.

- It was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel.

- It was committed in a cold, calculated, and premeditated manner without any pretense of moral or legal justification.

- The victim was a law enforcement officer engaged in the performance of his or her official duties.

- The victim was an elected or appointed public official engaged in the performance of his or her official duties if the motive for the capital felony was related, in whole or in part, to the victim’s official capacity.

- The victim was a person less than 12 years of age.

- The victim was particularly vulnerable due to advanced age or disability, or because the defendant stood in a position of familial or custodial authority over the victim.

- It was committed by a criminal gang member.

- It was committed by a person currently or formerly designated as a sexual predator.

- It was committed by a person subject to a restrictive order or a foreign protection order, and was committed against the person who obtained the injunction or protection order or any spouse, child, sibling, or parent of this person.

Florida statute also provides the death penalty for capital drug trafficking. A provision for capital sexual battery was found unconstitutional in the 2008 U.S. Supreme Court case Kennedy v. Louisiana. No one is on death row in the United States for drug trafficking.

Legal process

On June 14, 2013, Governor Rick Scott signed the Timely Justice Act of 2013. The law is designed to overhaul and speed up the process of capital punishment. It creates tighter time frames for a person sentenced to death to make appeals and post-conviction motions and imposes reporting requirements on case progress.[6]

In Hurst v. Florida (January 2014), the United States Supreme Court struck down part of Florida's death penalty law, saying it was not sufficient for a judge to determine the aggravating facts to be used in considering a death sentence. Under Florida law, the jury made a recommendation to the judge, with a finding by majority vote, and the judge separately determined aggravating facts other than what the jury proposed. The Court ruled that Florida's law violated the Sixth Amendment guaranteeing a jury trial.[7][8] It was unclear whether the ruling would apply retroactively to current condemned persons.

The Florida legislature passed a new statute to comply with the judgement in March 2014, and it also changed the sentencing method, requiring a 10 jurors supermajority to issue a sentence of death. If fewer than 10 jurors vote in favor of the death sentence, life imprisonment is imposed (there is no hung jury nor retrial).[9] Previously, the judge decided the sentence alone, and the jury gave only a non-binding advice.[10] This was also challenged and in October 2014, the Florida Supreme Court struck down the law by a 5–2 vote, finding that death sentences can only be handed down by a unanimous jury.[11]

In March 2017, the Florida legislature passed a new statute complying with the state supreme court holding that death sentences must be unanimous. It also provides that in case of a hung jury during the penalty phase of the trial, a life sentence is issued, even if a single juror opposed death (there is no retrial).[12]

Executions

Florida used public hanging under a local jurisdiction, overseen and performed by the sheriffs of the counties where the crimes took place. However, in 1923, the Florida Legislature passed a law replacing hanging with the electric chair and stated that all future execution will be performed under state jurisdiction inside prisons.[13][14] The electric chair became a subject of strong controversy in the 1990s after three executions received considerable media attention and were labeled as "botched" by opponents (Jesse Tafero in 1990, Pedro Medina in 1997, and Allen Lee Davis in 1999). While most states switched to the lethal injection, many politicians in Florida opposed giving up "Old Sparky", seeing it as a "deterrent".[15] Finally, after the Davis execution, lethal injection was enabled and became the default method.[16] Inmates, however, may still choose electrocution.[17]

In January 2014,[18] Wayne Doty asked the state to carry out his death sentence by electric chair, becoming the first inmate to do so since electrocution became optional.

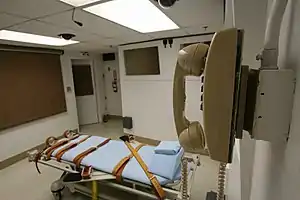

Today, the only execution chamber in Florida is located at Florida State Prison in Starke. When sentenced, male convicts who receive the death penalty are incarcerated at either Florida State Prison itself, or at Union Correctional Institution next door to Florida State Prison, while female convicts who are sentenced to death are incarcerated at Lowell Correctional Institution north of Ocala. Inmates are moved to the death row at Florida State Prison when their death warrant is signed.

Clemency

The Governor of Florida has the right to commute the death penalty, but only with positive recommendation of clemency from a Board, where he or she sits.[19]

Between 1925 and 1965, 57 commutations were granted out of 268 cases.[20] Since 1972, when the death penalty was re-instituted, only six commutations have been granted, all under the administration of Governor Bob Graham.[19]

See also

References

- Florida Department of Corrections. "Execution List - Florida Department of Corrections". Dc.state.fl.us. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- "Death Row Roster". Dc.state.fl.us. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 23, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Nation: At Issue: Crime and Punishment". Time. June 4, 1979.

- Florida Statutes § 921.141

- "Rick Scott signs bill speeding up capital punishment". NaplesNews.com. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- LIZETTE ALVAREZ, "Supreme Court Ruling Has Florida Scrambling to Fix Death Penalty Law", The New York Times, February 2, 2016, accessed February 3, 2016

- ADAM LIPTAK, "Supreme Court Strikes Down Part of Florida Death Penalty", The New York Times, January 12, 2016, accessed February 3, 2016

- Berman, Mark (March 7, 2016). "Florida death penalty officially revamped after Supreme Court struck it down". Washington Post. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- "HB 7101". Flsenate.gov. Florida state senate. Retrieved March 15, 2014.

- Klas, Mary Ellen; Ovalle, David (October 14, 2014). "Court again tosses state death penalty; ruling raises bar on capital punishment". Miami Herald. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- "SB 280: Sentencing for Capital Felonies". flsenate.gov. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- "Timeline: 1922-1924 - A History of Corrections in Florida". Dc.state.fl.us. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved 2016-07-21.

- "DPIC | Death Penalty Information Center". Deathpenaltyinfo.org. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Timeline: 1999 - A History of Corrections in Florida". Dc.state.fl.us. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved 2014-07-21.

- "Methods of Execution | Death Penalty Information Center". Deathpenaltyinfo.org. Archived from the original on July 3, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- Bradford County Public Records

- "Clemency | Death Penalty Information Center". Deathpenaltyinfo.org. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- Kathleen A. O'Shea, Women and the death penalty in the United States, 1900-1998, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999

External links

| Look up Florida flambe in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |