Canadian Expeditionary Force

The Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) was the designation of the field force created by Canada for service overseas in the First World War. The force fielded several combat formations on the Western Front in France and Belgium, the largest of which was the Canadian Corps, consisting of four divisions.

| Canadian Expeditionary Force | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms of Canada (1868) | |

| Active | August 1914–1919 |

| Disbanded | 1919 |

| Country | |

| Type | Army |

| Role | Land warfare |

| Size | 260 infantry battalions (619,646 enlistments) |

| Engagements | |

Expanded Elements

When it was deployed in 1914 the CEF was simply combat elements and became clear by 1915 support and administrative units needed to included in the Western Front.[1] After September 1915 the CEF expanded to include what was considered administrative corps:

- Canadian Cavalry Brigade

- Canadian Forestry Corps

- Canadian Machine Gun Corps

- Corps of Guides (Canada)

- HQ Corps of Military Staff Clerks

- Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps

- Royal Canadian Army Pay Corps

- Royal Canadian Army Service Corps

- Royal Canadian Army Veterinary Corps

- Royal Canadian Corps of Signals

- Canadian Military Engineers

- Canadian Postal Corps

- Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery

Reserves and Training

The CEF also had a large reserve and training organization in England, and a recruiting organization in Canada.

Recognition

In the later stages of the European war, particularly after their success at Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele, the Canadian Corps was regarded by friend and foe alike as one of the most effective Allied military formations on the Western Front.[2][3] In August 1918, the CEF's Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force travelled to revolution-torn Russia. It reinforced a garrison resisting Lenin's Bolshevik forces in Vladivostok during the winter of 1918–19. At this time, another force of Canadian soldiers were placed in Archangel, where they fought against Bolsheviks.

Composition

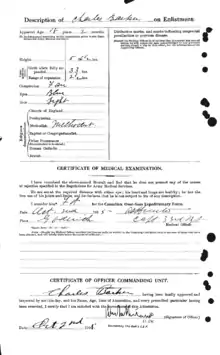

The Canadian Expeditionary Force was mostly volunteers; a bill allowing conscription was passed in August, 1917,[4] but not enforced until call-ups began in January 1918 (see Conscription Crisis of 1917). In all, 24,132 conscripts had been sent to France to take part in the final Hundred Days campaign.[5]

As a Dominion in the British Empire, Canada was automatically at war with Germany upon the British declaration.[6] Popular support for the war was found mainly in English Canada.[7] Of the first contingent formed at Valcartier, Quebec in 1914, about two-thirds were men who had been born in the United Kingdom. By the end of the war in 1918, at least half of the soldiers were British-born. Recruiting was difficult among the French-Canadian population, many of whom did not agree with supporting Canada's participation in the war;[8][9] one battalion, the 22nd, who came to be known as the 'Van Doos', was French-speaking. ("Van Doos" is an approximate pronunciation of the French for "22nd" - vingt-deuxième)

To a lesser extent, several other cultural groups within the Dominion enlisted and made a significant contribution to the Force including Indigenous people of the First Nations, Black Canadians as well as Black Americans.[11] Many British nationals from the United Kingdom or other territories who were resident in Canada and the United States also joined the CEF. A sizeable percentage of Bermuda's volunteers who served in the war joined the CEF, either because they were resident in Canada already, or because Canada was the easiest other part of the Empire and Commonwealth to reach from Bermuda (1,239 kilometres (770 miles) from Nova Scotia). As several CEF battalions were posted to the Bermuda Garrison before proceeding to France, islanders were also able to enlist there.[12] Although the Bermuda Militia Artillery and Bermuda Volunteer Rifle Corps both sent contingents to the Western Front, the first would not arrive there until June 1915. By then, many Bermudians had already been serving on the Western Front in the CEF for months. Bermudians in the CEF enlisted under the same terms as Canadians, and all male British Nationals resident in Canada became liable for conscription under the Military Service Act, 1917.

The CEF raised 260 numbered infantry battalions, two named infantry battalions (The Royal Canadian Regiment and Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry), 17 mounted regiments, 13 railway troop battalions, five pioneer battalions, four divisional supply trains, four divisional signals companies, a dozen engineering companies, over 80 field and heavy artillery batteries, fifteen field ambulance units, 23 general and stationary hospitals, and many other medical, dental, forestry, labour, tunnelling, cyclist, and service units. Two tank battalions were raised in 1918 but did not see service. Most of the infantry battalions were broken up and used as reinforcements, with a total of fifty being used in the field, including the mounted rifle units, which were re-organized as infantry. The artillery and engineering units underwent significant re-organization as the war progressed, in keeping with rapidly changing technological and tactical requirements.

Another entity within the Canadian Expeditionary Force was the Canadian Machine Gun Corps. It consisted of several motor machine gun battalions, the Eatons, Yukon, and Borden Motor Machine Gun Batteries, and nineteen machine gun companies. During the summer of 1918, these units were consolidated into four machine gun battalions, one being attached to each of the four divisions in the Canadian Corps.

The Canadian Corps with its four infantry divisions comprised the main fighting force of the CEF. The Canadian Cavalry Brigade also served in France. Support units of the CEF included the Canadian Railway Troops, which served on the Western Front and provided a bridging unit for the Middle East; the Canadian Forestry Corps, which felled timber in Britain and France, and special units which operated around the Caspian Sea, in northern Russia and eastern Siberia.[13]

Major battles

Battle of Ypres, 1915

The 1915 Battle of Ypres, the first engagement of Canadian forces in the Great War, exposed Canadian soldiers and their commanders to modern war. They had previously experienced the effects of shellfire and participated in aggressive trench raiding despite a lack of formal training and generally inferior equipment. They were equipped with the frequently malfunctioning Ross rifle, the older, lighter and less reliable Colt machine gun and an inferior Canadian copy of British webbing equipment that rotted quickly and fell apart in the wet of the trenches.

In April 1915, they were introduced to yet another facet of modern war, gas. The Germans employed chlorine gas to create a hole in the French lines adjacent to the Canadian force and poured troops into the gap. The Canadians, operating for the most part in small groups and under local commanders, fired into the flanks of the German advance, forcing it to turn its attention onto the Canadian sector. For three days, Canadian and reinforcing British units fought to contain the penetration with a series of counter-attacks while using handkerchiefs soaked in urine to neutralize effects of the gas. One in every three of the inexperienced but determined Canadians became a casualty. The senior Canadian officers were also inexperienced at first and lacked communications with most of their troops. Notable among these was Arthur Currie, a brigade commander later became the commander of the Canadian Corps and who appointed as his divisional commanders only those who had fought well in this engagement. The battle cost the British Expeditionary Force - BEF (of which the Canadian Corps was a part of) 59,275 men and the Canadian Expeditionary Force over 6000.[14]

Battle of the Somme, July–November 1916

According to historian G. W. L. Nicholson, "The Somme offensive had no great geographical objectives. Its purpose was threefold – to relieve pressure on the French armies at Verdun, to inflict as heavy losses as possible on the German armies, and to aid allies on other fronts by preventing any further transfer of German troops from the west." [15] The Canadian Corps was formed after receiving the 2nd and 3rd and later, 4th divisions. Its first commander was Lieutenant-General Edwin Alderson, who was soon replaced by Lieutenant-General Julian Byng, in time to repulse a German attack at Mont Sorrel in the Ypres sector in June 1916. while much of the BEF was moving toward the Somme. In this engagement, Major-General Malcolm Mercer, commander of the newly formed 3rd Division was killed; he was the most senior Canadian to be killed in the war.

The corps did not participate in the battles of the Somme until September, but these began on 1 July after a seven-day bombardment. British losses on the first day amounted to 57,470, which included the casualties of the Newfoundland Regiment serving in the British 29th Division. The regiment was annihilated when it attacked at Beaumont Hamel. By the time the four Canadian divisions of the corps participated in September, the Mark I Tank first appeared in battle. Only a few were available because the production time was long for the unfamiliar and unproven technology; those delivered were committed in order to aid the expected breakthrough. The psychological impact of them was considerable, with some claiming that they made many German soldiers surrender immediately, although the four months of sustained combat, high casualties among the defending Germans and the appearance of the fresh Canadian Corps were more likely factors in the increasing surrenders. The toll of the five-month campaign cannot be statistically verified by a single reliable source, however historians have estimated German losses at roughly 670,000 and an Allied total of 623,907.[15] The Canadian Corps suffered almost 25,000 casualties in this the final phase of the operation, but like the remainder of the BEF, it had developed, significant experience in the use of infantry and artillery and in tactical doctrine, preparation and leadership under fire.

Battle of Vimy Ridge, 9–12 April 1917

The Battle of Vimy Ridge had significance for Canada as a young nation. For the first time the Canadian Corps, with all four of its divisions attacked as one. This Canadian offensive amounted to the capture of more land, prisoners and armaments than any previous offensive.[15] The main offensive tactic was the creeping barrage, an artillery strike combined with constant infantry progression through the battlefield.[note 1]

Passchendaele, October – November 1917

In August 1917, the Canadian Corps attacked Lens as a distraction to allow two armies of the BEF to begin the Third Battle of Ypres, the attack on Passchendaele Ridge. The Corps, led by Lieutenant General Arthur Currie, captured Hill 70 overlooking Lens and forced the Germans to launch more than twenty counter-attacks in attempting to remove the threat to its flank. The Ypres offensive began with the swift capture of the Messines Ridge, but weather, concrete defences and the lack of any other concurrent Allied effort meant that the BEF fought a muddy, bloody campaign against the main German force for two months. The BEF, including the ANZACs, pushed to within two kilometres of the objective with very high casualties and in ever-deepening mud.

By September, it became clear that a fresh force would need to be brought in for the final push. With the situation in Italy and within the French army deteriorating, it was decided to continue the push and Currie was ordered to bring in the Canadian Corps. He insisted on time to prepare, on reorganizing the now-worn down artillery assets and on being placed under command of General Plumer, a commander he trusted. The first assault began on October 26, 1917. It was designed to achieve about 500 meters in what had become known as "bite and hold" tactics but at great cost (2,481 casualties) and made little progress. The second assault on October 30 cost another 1,321 soldiers and achieved another 500 metres but reached the high ground at Crest Farm. On November 6, after another round of preparations, a third attack won the town of Passchendaele, for another 2,238 killed or wounded. The final assault to capture the remainder of Passchendaele Ridge began on November 10 and was completed the same day. Nine Canadians earned the Victoria Cross in an area not much bigger than four football fields and the Canadian Corps completed the operation after it had taken the BEF three months to advance the eight kilometres onto the ridge. The Canadian Corps suffered 15,654 battle casualties in the muddiest, best-known battle of the Great War.[16]

Final count

After extensive experience and success in battle from the Second Battle of Ypres, through the Somme and particularly in the Battle of Arras at Vimy Ridge in April 1917, and Passchendaele the Canadian Corps came to be regarded as an exceptional force by both Allied and German military commanders.[17][18] Since they were mostly unmolested by the German army's offensive manoeuvres in the spring of 1918, the Canadians were ordered to spearhead the last campaigns of the War from the Battle of Amiens on August 8, 1918, which ended in a tacit victory for the Allies when the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918.

The Canadian Expeditionary Force lost 60,661 men killed or died during the war, representing 9.28% of the 619,636 who enlisted.

End of the CEF

The CEF was a special force, distinct from the Canadian Militia which mobilized in 1914 on a limited basis for home defence and to assist with the recruitment and training of the CEF. In 1918 the militia personnel active in Canada were granted CEF status, to simplify administration in the wake of conscription coming into force. Beginning in 1918, in anticipation of the disbandment of the CEF, plans for the re-organization of the militia were initiated, guided largely by the deliberations of the Otter Commission, convened for this purpose. Among the commission's recommendations was a plan by which individual units of the Canadian Militia, notably infantry and cavalry regiments, would be permitted to perpetuate the battle honours and histories of the CEF units that had fought during the war.[19]

During the latter part of the war, the Canadian Military Hospitals Commission reported on provision of employment for members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force on their return to Canada, and the re-education of those who were unable to follow their previous occupations because of disability.[20]

Equipment

Animals

Officially an infantry division would be classified at full animal strength at 5,241 horses and mules, 60.7 percent or 3,182 of these animals were part of the infantry division's artillery branch.[21]

Besides mounted and cavalry units, the CEF used horses, mules, donkeys and cattle to transport gun pieces on the battle front as motorised vehicles would not be able to handle rough terrain.[22][23]

At the start of the war over 7,000 horses were brought over to England and Europe from Canada[24] and by the end of the war over 8 million horses had been lost in the course of fighting in Europe.[22]

Dogs and carrier pigeons were employed as messengers in the front.[22]

With horses, wagons were also used to transport equipment as well.[24]

Vehicles

- Armoured carriers and armoured tractors

| Type | Origin | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mark I tank | Training tank | |

| Mark IV tanks | They were operated by CEF crews during battle, but they belonged to the British Army | |

| Autocar trucks | 20 cars ordered: 8 machine gun carriers (motor Maxim MG battery), 5 ammo and supply cars, 4 officer transport, 1 gasoline carrier, 1 repair vehicle, 1 ambulance; 1 MG carrier displayed at Canadian War Museum[25] |

Small arms

.303 rifles

| Model/Type | Period or Years in Use | Manufacturer/Origins |

|---|---|---|

| Ross Rifle Mark I and Ross Mark II (multiple * variants) | 1905–1913 | |

| Ross Rifle Mark III | 1913–1916 | |

| Lee–Enfield (SMLE) Mark III | 1916–1943 |

| Model/Type | Period or Years in Use | Manufacturer/Origins |

|---|---|---|

| Colt "New Service" Revolver—1900-1928 (also used by the NWMP and RCMP from 1905–1954) | ||

| Colt Model 1911 Pistol—1914-1945 | ||

| Smith & Wesson 2nd Model "Hand Ejector" Revolver—1915-1951 |

| Model/Type | Period or Years in Use | Manufacturer/Origins |

|---|---|---|

| Webley Mark VI Revolver | ||

| Enfield No. 2 MkI Revolver |

| Model/Type | Period or Years in Use | Manufacturer/Origins |

|---|---|---|

| Pattern 1907 bayonet | ||

| Ross Bayonet (for 1905 and 1910 rifles) |

Machine guns, light machine guns and other weapons

| Model/Type | Period or Years in Use | Manufacturer/Origins |

|---|---|---|

| Colt Machine Gun 1914-1916 | ||

| Vickers Machine Gun 1914-1950s | ||

| Lewis Machine Gun—1916-c.1945 |

Ammunition

| Model/Type | Period or Years in Use | Manufacturer/Origins |

|---|---|---|

| .303 British | ||

| .455 Webley |

Uniforms, load bearing and protective equipment

| Model/Type | Period or Years in Use | Manufacturer/Origins |

|---|---|---|

| Service dress 1903-1939 | ||

| Canadian pattern and British pattern |

Load bearing equipment

| Model/Type | Period or Years in Use | Manufacturer/Origins |

|---|---|---|

| Oliver Pattern Equipment 1898-19?? | ||

| 1908 pattern web equipment (British & Canadian variants) | Canadian Variant had ammunition pouches to hold ammo packets for use with Mk. II Ross Rifles as they were not charger loading | |

| Canadian Pattern 1913 Equipment | Canadian trials with modernizing the P08 web gear. the PPCLI went overseas equipped with P13 gear. Many aspects would be utilized in later sets of gear | |

| British Pattern 1914 Equipment | Wartime economy equipment | |

| Canadian Pattern 1915 Equipment | Modification of 1899 Oliver Pattern gear | |

| Canadian Pattern 1916 Dismounted Equipment | Upgrade of Pattern 1915 equipment |

Head dress

| Model/Type | Period or Years in Use | Manufacturer/Origins |

|---|---|---|

| Glengarry | ||

| Tam o'shanter | ||

| Field Service Cap | ||

| Brodie helmet | after 1915 |

Labour

Chinese labourers were also brought over to Europe, especially the Canadian Railway Troops.[26] From 1917 to 1918 84,000 Chinese labourers were recruited for the Chinese Labour Corps from China (via Shandong Province) that were shipped to Canada and then some to the Western Front. Many of these labourers died in Belgium and France.[27]

In literature

A considerable part of the plot of the novel Fifth Business by Robertson Davies describes the protagonist's experiences as a soldier of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

See also

- British Army

- Canadian Militia

- Military history of Canada during World War I

- List of Canadian battles during the First World War

- Canadian official war artists

- Canadian Corps

- List of mounted regiments in the Canadian Expeditionary Force

- List of infantry battalions in the Canadian Expeditionary Force

- Currie Hall

- Bermudians in the Canadian Expeditionary Force

Notes

- The Canadian artillery was reinforced with British units and its planning was directed by a British officer, Major Alan Brooke, serving with the Corps HQ.

References

- https://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/life-at-the-front/military-structure/the-canadian-expeditionary-force/

- Godefroy, A. (April 1, 2006). "Canadian Military Effectiveness in the First World War." In The Canadian Way of War: Serving the National Interest Bernd Horn (ed.) Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-612-2

- Comeau, Robert (November 12, 2008). "Passchendaele cemented Canada's world role". National Defence and the Canadian Forces. The Maple Leaf. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013.

- Amy J. Shaw (1 July 2009). Crisis of Conscience: Conscientious Objection in Canada during the First World War. UBC Press. pp. 28, 199. ISBN 978-0-7748-5854-0.

- 1951-, Dennis, Patrick M. (2017). Reluctant warriors : Canadian conscripts and the Great War. Vancouver, British Columbia: UBC Press. ISBN 9780774835978. OCLC 985071597.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Gordon L. Heath (13 January 2014). Canadian Churches and the First World War. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-63087-290-8.

- René Chartrand (20 December 2012). The Canadian Corps in World War I. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-78200-906-1.

- World War I: The Definitive Visual History. DK Publishing. 21 April 2014. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-4654-3490-6.

- Brock Millman (6 April 2016). Polarity, Patriotism, and Dissent in Great War Canada, 1914-1919. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-6763-1.

- Original author is unknown. The photo comes from a private family collection. They would have been taken in late 1915 or early 1916, before their deployment.

- Morton, Desmond. When Your Number's Up

- Richard Holt (2017). "4". Filling the Ranks: Manpower in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1918. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-7735-4877-0.

- Stacey, C. & N. Hillmer "Canadian Expeditionary Force". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Dancocks, Daniel G. Welcome to Flanders Fields: the First Canadian Battle of the Great War : Ypres, 1915. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1988

- Nicholson, Gerald W. L. Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1919: Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War. Ottawa: R. Duhamel, Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery, 1962.]

- [Bercuson, David Jay. The Fighting Canadians: Our Regimental History from New France to Afghanistan. Toronto: HarperCollins, 2008.]

- Nathan M. Greenfield (10 October 2008). Baptism of Fire: The Second Battle of Ypres and the Forging of Canada, April 1915. HarperCollins. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-00-639576-8.

- William Kaye Lamb (1971). Canada's Five Centuries: From Discovery to Present Day. McGraw-Hill Company of Canada. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-07-092907-4.

- "Otter Committee". www.canadiansoldiers.com. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- The Provision of Employment for Members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force on Their Return to Canada, and the Re-Education of Those Who Are Unable to follow their previous occupations because of disability. Canada Military Hospitals Commission Nabu Press August 2010. This is a reproduction of a book published before 1923.

- Nance, Susan (2015). Historical Animal. New York: Syracuse University. p. 278. ISBN 9780815634065.

- "Canadian Expeditionary Force - Library and Archives Canada Blog". thediscoverblog.com. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/military-heritage/first-world-war/Documents/cavalry.pdf

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-04-06. Retrieved 2009-02-23.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.patriotfiles.com/forum/showthread.php?t=109773

- http://www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhh-dhp/his/docs/CEF_e.pdf

- Ma, Suzanne (11 November 2011). "Chinese recruited for war had secret passage through Canada". ctvnews.ca. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

Further reading

- Berton, Pierre (1986). Vimy. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. ISBN 0-7710-1339-6

- Christie, Norm. For King & Empire, The Canadians at Amiens, August 1918. CEF Books, 1999

- Christie, Norm. For King & Empire, The Canadians at Arras, August–September 1918. CEF Books, 1997

- Christie, Norm. For King & Empire, The Canadians at Cambrai, September–October 1918. CEF Books, 1997

- Dancocks, Daniel G. Spearhead to Victory – Canada and the Great War, Hurtig Publishers, 1987

- Cook, Tim. "At the Sharp End - Canadians Fighting the Great War 1914-1916 Vol. One", Viking Canada, 2007

- Cook, Tim. "Shock Troops - Canadians Fighting the Great War 1917-1918 Vol. Two", Viking Canada, 2008

- Morton, Desmond and Granatstein, J.L. Marching to Armageddon. Lester & Orpen Dennys Publishers, 1989

- Morton, Desmond. When Your Numbers Up. Random House of Canada, 1993

- Newman, Stephen K. With the Patricia's in Flanders: 1914–1918. Bellewaerde House Publishing, 2000

- Nicholson, G. W. L. (1962). Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1919 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War. Ottawa: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationary. OCLC 59609928. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- Schreiber, Shane B. Shock Army of the British Empire – The Canadian Corps in the Last 100 Days of the Great War. Vanwell Publishing Limited, 2004

- Canada Military Hospitals Commission The Provision of Employment for Members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force on Their Return to Canada, and the Re-Education of Those Who Are Unable to follow their previous occupations because of disability. Canada Military Hospitals Commission Nabu Press August 2010. This is a reproduction of a book published before 1923.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canadian Expeditionary Force. |

Government links

- The First World War from Library Archives Canada

- Remembrance: The First World War from Veterans Affairs Canada

- Oral Histories of the First World War: Veterans 1914-1918 from Library Archives Canada

- Official Histories - Free online PDF books on the C.E.F. from The Department of National Defense

Museums and media links

Other links

- Canadian Great War Project

- The C.E.F. Paper Trail

- The C.E.F. Study Group

- Central Ontario Branch Western Front Association

- Regimentalrogue website has a variety of information on researching soldiers of the CEF and the conditions of the war

- canadiansoldiers.com