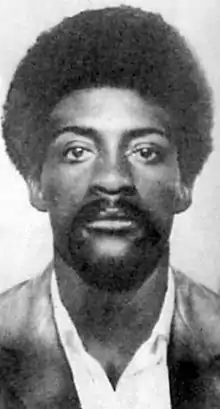

Bunchy Carter

Alprentice "Bunchy" Carter (October 12, 1942 – January 17, 1969) was an American activist. Carter is credited as a founding member of the Southern California chapter of the Black Panther Party. Carter was shot and killed by a rival group, and is celebrated by his supporters as a martyr in the Black Power movement in the United States. Carter is portrayed by Gaius Charles in the 2015 TV series Aquarius.[2]

Bunchy Carter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 12, 1942 Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Died | January 17, 1969 (aged 26) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Murder |

| Resting place | Woodlawn Memorial Park, Compton, Los Angeles, California, U.S.[1] |

| Other names | Mayor of the Ghetto |

| Citizenship | American |

| Occupation | Activist |

| Years active | 1967–1969 |

| Known for | Leader of the Los Angeles chapter Black Panther Party |

| Political party | Black Panther Party |

Early life

In the early 1960s Carter was a member of the Slauson street gang in Los Angeles. He became a member of the Slauson "Renegades", a hard-core inner circle of the gang, and earned the nickname "Mayor of the Ghetto". Carter was eventually convicted of armed robbery and was imprisoned in Soledad prison for four years. While incarcerated Carter became influenced by the Nation of Islam and the teachings of Malcolm X, and he converted to Islam. He would later renounce Islam after an encounter with Eldridge Cleaver citing contradictions and focus on the black liberation struggle. After his release, Carter met Huey Newton, one of the founders of the Black Panther Party, and was convinced to join the party in 1967.

Southern California chapter of the Black Panthers

In early 1968, Carter formed the Southern California chapter of the Black Panther Party (BPP) and became a leader in the group. Like all Black Panther chapters, the Southern California chapter studied politics, read Party literature, and received training in firearms and first aid. They also began the "Free Breakfast for Children" program which provided meals to the poor in the community. The chapter was very successful, gaining 50–100 new members each week by April 1968. Notable members included Elaine Brown and Geronimo Pratt. The Black Panthers were referred to as "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country" by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, and the party was targeted by the secret FBI operation known as COINTELPRO. As later revealed in Senate testimony, the FBI worked with the Los Angeles Police Department to harass and intimidate party members.

In 1968 and 1969, numerous false arrests and warrantless searches were documented, and several members were killed in altercations with the police. "The Breakfast for Children Program," wrote Hoover in an internal FBI memo in May 1969, "represents the best and most influential activity going for the BPP and, as such, is potentially the greatest threat to efforts by authorities to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for." The breakfast program was effectively shut down by daily arrests of members; however, those charges were usually dropped within a week. Later in 1969, Hoover sent orders to FBI field offices: "exploit all avenues of creating dissension within the ranks of the BPP", and "submit imaginative and hard-hitting counterintelligence measures aimed at crippling the BPP". In Southern California, the Black Panthers were also rivals of a black nationalist group called Organization Us (usually referred to as "US"), founded by Ron Karenga. The groups had very different aims and tactics, but often found themselves competing for potential recruits. This rivalry came to a head in 1969, when the two groups supported different candidates to head the Afro-American Studies Center at UCLA.

1969 UCLA shooting

During a meeting of the Black Student Union at UCLA's Campbell Hall on January 17, 1969, Bunchy Carter and another BPP member named John Huggins were heard making derogatory comments about Ron Karenga, the head of Organization US. Other accounts mention a heated argument between US members and Panther Elaine Brown. An altercation ensued during which Carter and Huggins were shot to death.

BPP members originally insisted that the event was a planned assassination, claiming that there was a prior agreement that no guns would be brought to the meeting, that BPP members were not armed, and that Organization Us members led by Ron Karenga were. Organization Us members maintained the meeting was a spontaneous event. Former BPP deputy minister of defense Geronimo Pratt, Carter's head of security at the time, later stated that rather than a conspiracy, the UCLA incident was a spontaneous shootout. The person who allegedly shot Carter and Huggins, Claude Hubert, was never found.

During the Church Committee hearings in 1975, evidence came to light that under the FBI's COINTELPRO actions, FBI agents had deliberately fanned flames of division and enmity between the BPP and Organization US. Death threats and humiliating cartoons created by the FBI were sent to each group, made to look as if they originated with the other group, with the explicit intention of inciting deadly violence and division.

Following the UCLA incident, brothers George and Larry Stiner and Donald Hawkins turned themselves in to the police, who had issued warrants for their arrests. They were convicted for conspiracy to commit murder and two counts of second-degree murder, based on testimony given by BPP members. The Stiner brothers both received life sentences and Hawkins served time in California's Youth Authority Detention. The Stiners escaped from San Quentin in 1974. George Stiner has not been recaptured. Larry Stiner survived as a fugitive for 20 years, living in Suriname. He surrendered in 1994 in order to try to negotiate help for his family suffering from turmoil in Suriname. He was immediately returned to San Quentin to serve out his life sentence. The State Department reneged on the agreement to let his family come to the U.S., saying he did not qualify as a sponsor due to being incarcerated. His children remained in precarious and impoverished circumstances for eleven years, until they were able to come to the U.S. in 2005. His wife died before she could come herself. Larry Stiner was paroled in 2015.[3]

Aftermath

The LAPD responded to the attack by raiding an apartment used by the Black Panthers and arresting 75 members, including all remaining leadership of the chapter, on charges of conspiring to murder US members in retaliation. (These charges were later dropped.) This reaction fueled claims that US was being used by the FBI to target the Black Panthers. Later in 1969, two other Black Panther members were killed and one other was wounded by US members.

The Black Student Union (BSU) at UCLA was shocked and devastated by the murders. The chair of communications, Webster Moore, filled the void by reopening Campbell Hall. As the acting Chair, Webster organized a Central Committee that interviewed and facilitated the hiring of a former Freedom Rider in Mississippi, Dr. Robert Singleton, as the Director of the Center for African American Studies. Singleton also became the founding Director of UCLA’s Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies. As BSU Chair, Webster also served on the committee that brought Angela Davis as the 1st Black Philosopher Professor to UCLA. The BSU, while working with the EOP, provided a channel for high school students to eventually enroll into UCLA. The first Black Student Unions were established in the participating high schools. On December 9, 1969, Webster and Angela walked together down Central avenue to bring a halt to the massive shootout between 6 Black Panthers and over 200 police. The Panthers surrendered before they reached them, but there were no casualties. Webster Moore was later beaten unconscious at UCLA by Police during a campus demonstration against the Kent State shootings.[4]

Richard Held was promoted to Special Agent in Charge of the San Francisco office. In the years following the deaths of Carter and Huggins, the Black Panther party became more suspicious of outsiders and became more focused on defense rather than community improvement. The group was more marginalized and officially disbanded in 1982. Bunchy Carter had a son who was born in April 1969, after Carter was murdered. His son, coincidentally, attended California State Long Beach (1987–1992), while Ron Karenga was the chairman of the Black Studies Department.

References

- Pharr, Wayne (July 1, 2014). Nine Lives of a Black Panther: A Story of Survival. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 9781613749166 – via Google Books.

- Ausiello, Michael (July 14, 2014). "Grey's Anatomy's Gaius Charles Joins NBC's Charles Manson Drama Aquarius".

- Radio, Southern California Public (March 28, 2015). "Gang chief, international fugitive among dozens paroled under California policy". Southern California Public Radio.

- UCLA & The Angela Davis Case-Webster E Moore

Further reading

- Alex A. Alonso, Territoriality Among African-American Street Gangs in Los Angeles, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, 1999.

- Elaine Brown, A Taste of Power: A Black Woman's Story, Doubleday, New York, 1992.

- Scot Brown, Fighting for US: Maulana Karenga, the US Organization, and Black Cultural Nationalism, NYU Press, New York, 2003.

- The Black Panther: Black Community News Service newspaper, Berkeley, Spring 1991.

- Kit Kim Holder, The History of the Black Panther Party 1966–1972: A Curriculum Tool for Afrikan Amerikan Studies, 1990, Amherst College Library, Amherst, Mass.

- Huey Newton, War Against the Panthers: A Study of Repression in America, University of California Santa Cruz, June 1980.

- Ward Churchill and Jim Vander Wall, Agents of Repression: The FBI's Secret Wars Against the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Movement, South End Press: Boston, 1990.

- University Archives. Subject Files (Reference Collection)

External links

- The FBI's War on the Black Panther Party's Southern California Chapter by the Maoist Internationalist Movement

- Los Angeles Gangs from streetgangs.com

- Civil Rights Movement cemented in UCLA history by the Daily Bruin, UCLA

- Children of the Revolutionary LA Weekly feature on the 1969 UCLA shootout that killed John Huggins and Bunchy Carter.

- Bunchy Carter at Find a Grave