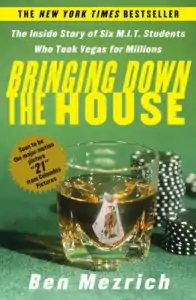

Bringing Down the House (book)

Bringing Down the House: The Inside Story of Six MIT Students Who Took Vegas for Millions is a 2003 book by Ben Mezrich about a group of MIT card counters commonly known as the MIT Blackjack Team. Though the book is classified as non-fiction, the Boston Globe alleges that the book contains significant fictional elements, that many of the key events propelling the drama did not occur in real life, and that others were exaggerated greatly.[1] The book was adapted into the movies 21 and The Last Casino.

| |

| Author | Ben Mezrich |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Blackjack |

| Genre | Non-fiction |

| Publisher | Free Press |

Publication date | 9 September 2003 |

| Media type | Print, e-book |

| Pages | 257 pp |

| ISBN | 1-4176-6563-7 |

| Followed by | Busting Vegas |

Synopsis

The book's main character is Kevin Lewis, an MIT graduate who was invited to join the MIT Blackjack Team in 1993. Lewis was recruited by two of the team's top players, Jason Fisher and Andre Martinez. The team was financed by a colorful character named Micky Rosa, who had organized at least one other team to play the Vegas strip. This new team was the most profitable yet. Personality conflicts and card counting deterrent efforts at the casinos eventually ended this incarnation of the MIT Blackjack Team.

Characters

Kevin Lewis

Although not revealed in the book, Kevin Lewis's real name is Jeff Ma, an MIT student who graduated with a degree in Mechanical Engineering in 1994. Ma has since gone on to found a fantasy sports company called Citizen Sports (a stock market simulation game).[2]

Mezrich acknowledges that Lewis is the sole major character based on a single, real-life individual; other characters are composites. Nonetheless, Lewis does things in the book that Ma himself says did not occur.[1]

Jason Fisher

One of the leaders of the team, Jason Fisher, is modeled in part after Mike Aponte. After his professional card counting career, Aponte went on to win the 2004 World Series of Blackjack, and started a company called the Blackjack Institute. Mike also has his own blog.

Micky Rosa

The team's principal leader, Micky Rosa is a composite character based primarily on Bill Kaplan, JP Massar, and John Chang.[1] Bill Kaplan founded and led the MIT Blackjack Team in the 1980s and co-managed the team with Massar and Chang from 1992 to 1993, during which time Jeff Ma joined the then nearly 80 person team.[3][4] Chang has questioned the book's veracity, telling The Boston Globe, "I don't even know if you want to call the things in there exaggerations, because they're so exaggerated they're basically untrue."[1] Whether the MIT Blackjack Team was "founded ... in the 1980s" is in dispute. An article in The Tech, January 16, 1980, suggests that Roger Demaree and JP Massar were already running the team and teaching a hundred MIT students to play blackjack by the third week of the 1980s, implying that the team had been founded in the late 1970s, before Kaplan joined, although Demaree and Massar have mostly avoided publicity.[5]

Controversy

Boston Magazine and Boston Globe articles

In its March 2008 edition, Boston magazine ran an article investigating long-lingering claims that the book was substantially fictional.[6] The Boston Globe followed up with a more detailed story on April 6, 2008.[1]

Though published as a factual account and originally categorized under "Current Events" in the hardcover Free Press edition, Bringing Down the House "is not a work of 'nonfiction' in any meaningful sense of the word," according to Globe reporter Drake Bennett. Mezrich not only exaggerated freely, according to sources for both articles, but invented whole parts of the story, including some pivotal events in the book that never happened to anyone.

Disclaimer and leeway

The book contains the following disclaimer:

The names of many of the characters and locations in this book have been changed, as have certain physical characteristics and other descriptive details. Some of the events and characters are also composites of several individual events or persons.[7]

This disclaimer allows broad leeway to take real events and real people and alter them in any way the author sees fit. But Mezrich went further, both articles say.

Historical inaccuracies

The following events described in Bringing Down the House did not occur:

- Underground Chinatown Casino. The underground casino used for Kevin's final test (pp. 55–59) is entirely imaginary, according to Mike Aponte and Dave Irvine.[6]

- Use of Strippers to Cash Out Chips. Also according to Aponte and Irvine,[6] strippers were never recruited to cash out the team's chips, as described on pp. 149–153.

- Shadowy Investors. The "shadowy investors" first referenced on p. 3 are a major source of intrigue for Mezrich's story, but did not exist, according to Aponte and Irvine.[6] The investors in the team included the players, one of Kaplan's college roommates, a few of Kaplan's Harvard Business School section mates, and Kaplan's friends and family members.

- Physical Assault. The scene in which Fisher is beaten up (pp. 221–225) is imaginary. "No one was ever beaten up,"[6] according to Aponte and Irvine. Moreover, Jeff Ma claims they have never been roughed up by the casinos they played in. Still there were times when casino employees had tried to intimidate the members of the team.

- Player Forced to Swallow Chip. In a scene on pp. 215–218, Micky Rosa recounts a story in which Vincent Cole—a private investigator for Plymouth Investigations—forces a member of a count team to swallow a purple casino chip while detaining the player in a back room. Sources in the Globe described the story as "implausible," and none recalled having heard it.[1]

- Theft of $75,000. One MIT player, Kyle Schaffer, did lose $20,000 when it was stolen from a desk drawer.[1] Mezrich inflates the amount of the theft by 275% and turns the desk drawer into a safe pried dramatically from a wall. Moreover, the robbery scene (pp. 240–244) creates the impression that a team member or Vincent Cole was the likely culprit. Schaffer says the theft was likely unrelated to blackjack, noting that $100,000 or more in casino chips also inside the drawer was left untouched ("strongly suggesting that the thieves had no idea of their worth"[1]).

- Forcible Entry to Kevin Lewis's Apartment. Kevin hurries from the scene of the robbery to his own apartment (pp. 244–245) to make sure all is well. Nothing has been stolen, but Kevin finds "a single purple casino chip sitting on his kitchen table." The implication is that the chip is a calling card left by Vincent Cole as a warning to Kevin. This scene again asks readers to accept that the chip-swallowing story is factual (or at least was actually in circulation among MIT counters as a myth).

Sequel

Though not originally intended to have a sequel, Mezrich followed this book with Busting Vegas (ISBN 0060575123). Busting Vegas is about another splinter group from the MIT Blackjack Team. The events depicted in Busting Vegas actually took place before Bringing Down the House. Despite heavy marketing, Busting Vegas did not do as well as Bringing Down the House. It did, however, briefly appear on The New York Times Best Seller list. Despite again being listed as non-fiction Busting Vegas showed similar inaccuracies in recounting the facts with the main character Semyon Dukach contesting several of the events depicted in the book.[8]

Film adaptation

A film adaptation of the book, titled 21 (so as not to cause confusion with the unrelated 2003 Queen Latifah vehicle Bringing Down the House), was released in theaters on March 28, 2008.[9] The film is from Columbia Pictures and was directed by Robert Luketic.

Kevin Spacey produced the film, and also portrays the character of Micky Rosa. Other cast members include Laurence Fishburne, Kate Bosworth, Jim Sturgess, Jacob Pitts, Liza Lapira, Aaron Yoo, and Sam Golzari.[10][11] Jeff Ma, Bill Kaplan, and Henry Houh, another team player from the 1990s, have brief cameo roles in the movie. 21 was filmed outside the buildings of MIT, in Boston University classrooms and dorms, throughout Cambridge and Boston, and in Las Vegas.

Says Mezrich, "...Kevin Spacey came to me about making a movie. He read the Wired adaptation[12] of the book and became interested... The funny thing is filming may take place in casinos such as The Mirage and Caesar's Palace, where the real thing happened."[13]

Notes

- Bennett, Drake (2008-04-06). "House of cards". Boston Globe. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- "About Us / The Protrade Team" (English). Citizen Sports Network. 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-04-15. Retrieved 2008-04-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) The Allston-Brighton Tab: Kaplan Inspires Hollywood Film '21.' Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-02-16. Retrieved 2012-02-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) MickeyRosa.com 'House of Cards' Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- http://tech.mit.edu/archives/VOL_099/TECH_V099_S0589_P002.pdf

- Gonzalez, John (March 2008). "Ben Mezrich: Based on a True Story". Boston magazine. Metrocorp, Inc. Archived from the original on 2008-12-18. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- Mezrich, Ben, Bringing Down the House: The Inside Story of Six M.I.T. Students Who Took Vegas for Millions (New York: Free Press, 2002), p. iv.

- "ThePOGG Interviews - Semyon Dukach - MIT Card Counting Team Captain". Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- Production Weekly: Luketic Hacking Las Vegas. Retrieved March 6, 2007. Archived January 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- benmezrich.com. Retrieved March 6, 2007 Archived May 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Kevin Der (2005-09-30). "MIT Alumnus and 'Busting Vegas' Author Describe Experience of Beating the House". The Tech. Retrieved 2008-03-29.

- Mezrich, Ben (September 2002). "Wired 10.09: Hacking Las Vegas". Wired. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- Zhang, Jenny (2002-10-25). "Card Counting Gig Nets Students Millions". The Tech, MIT Newspaper (Issue 50 ed.). Retrieved 2008-05-14.

External links

- Chet Curtis Report on NECN - "Bringing Down the House with Bill Kaplan"

- Adaptation of the book in Wired issue 10.09

- Mike Aponte's website

- Luck is for Losers INC Magazine August 2008