Box turtle

Box turtles are North American turtles of the genus Terrapene. Although box turtles are superficially similar to tortoises in terrestrial habits and overall appearance, they are actually members of the American pond turtle family (Emydidae). The twelve taxa which are distinguished in the genus are distributed over six species. They are largely characterized by having a domed shell which is hinged at the bottom, allowing the animal to retract its head and legs and close its shell tightly to protect itself from predators.

| Box turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

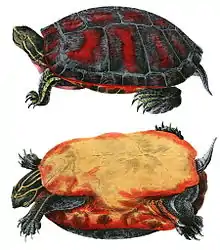

| Florida box turtle, Terrapene carolina bauri | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Emydidae |

| Subfamily: | Emydinae |

| Genus: | Terrapene Merrem, 1820[1] |

| Type species | |

| Terrapene carolina | |

| Species[1] | |

|

Terrapene carolina | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Cistuda Fleming, 1822 | |

Taxonomy and genetics

The genus name Terrapene was coined by Blasius Merrem in 1820 as a genus separate from Emys, describing those species which had a sternum separated into two or three divisions, and which could move these parts independently.[3] He placed in this genus, among others, Terrapene boscii (now accepted to be Kinosternon subrubrum subrubrum) and Terrapene carolina (but under the name Terrapene clausa). Also several Asian box turtles have been formerly classified within the genus Terrapene; e.g., Terrapene bicolor (now Cuora amboinensis couro) and Terrapene culturalia (now Cuora flavomarginata).[1] Currently, six species are classified within the genus and 12 taxa are distinguished:[1]

- Common box turtle, Terrapene carolina (Linnaeus, 1758) (type species)[2]

- Florida box turtle, Terrapene carolina bauri Taylor, 1895

- Eastern box turtle, Terrapene carolina carolina (Linnaeus, 1758)

- Gulf Coast box turtle, Terrapene carolina major (Agassiz, 1857)

- Terrapene carolina putnami O.P. Hay, 1906 (extinct)[4]

- Three-toed box turtle, Terrapene carolina triunguis (Agassiz, 1857)

- Coahuilan box turtle, Terrapene coahuila Schmidt & Owens, 1944

- Mexican box turtle, Terrapene mexicana (Gray, 1849)

- Spotted box turtle, Terrapene nelsoni Stejneger, 1925

- Northern spotted box turtle, Terrapene nelsoni klauberi Bogert, 1943

- Southern spotted box turtle, Terrapene nelsoni nelsoni Stejneger, 1925

- Western box turtle, Terrapene ornata, (Agassiz, 1857)

- Ornate box turtle, Terrapene ornata ornata (Agassiz, 1857)

- Desert box turtle, Terrapene ornata luteola H.M. Smith & Ramsey, 1952

- Yucatán box turtle, Terrapene yucatana (Boulenger, 1895)

Box turtles have diploid somatic cells with 50 chromosomes.[5]

Ecology and behavior

Life cycle and predation

Once maturity is reached, the chance of death seems not to increase with age. The survivorship curve of box turtles is therefore probably similar to that of other long-living turtles. The average life span of adult box turtles is 50 years, while a significant portion lives over 100 years. The age of a growing box turtle in the wild cannot be accurately estimated by counting the growth rings on the scutes; Their growth is directly affected by the amount of food, types of food, water, illness, and more. Box turtle eggs are flexible, oblong and are (depending on the taxon) on average 2–4 cm long weighing 5-11 g. The normal clutch size is 1-7 eggs. In captivity and in the southern end of their range, box turtles can have more than one clutch per year, while the average clutch size is larger in more northern populations.[6] Turtles can defend themselves from predation by hiding, closing their shell and biting. The risk of death is greatest in small animals due to their size and weaker carapace and plastron. While the shell of an adult box turtle is seldom fractured, the box turtle is still vulnerable to surprise attacks and persistent gnawing or pecking. Common predators are mammals like minks, skunks, raccoons, dogs and rodents, but also birds (e.g. crows, ravens) and snakes (e.g. racers, cottonmouths) are known to kill box turtles.[7]

Diet

North American box turtles are omnivores with a varied diet, as a box turtle will "basically eat anything it can catch". Invertebrates (amongst others insects, earth worms, millipedes) form the principal component, but the diet also consists for a large part (reports range from 30-90%) of vegetation. The diet is amended with fruits (amongst others from cacti, apples and several species of berry) and gastropods (Heliosoma, Succinea).[8] While reports exist that during their first five to six years, box turtles are primarily carnivorous and adults are mostly herbivorous, there is no scientific basis for such a difference.[8]

Distribution and habitat

Box turtles are native to North America. The widest distributed species is the common box turtle which is found in the United States (subspecies carolina, major, bauri, triunguis; south-central, eastern, and southeastern parts) and Mexico (subspecies yukatana and mexicana; Yucatán peninsula and northeastern parts). The western box turtle is endemic to the south-central and southwestern parts of the U.S. (and adjacent Mexico) while the spotted box turtle is endemic to northwestern Mexico only. The Coahuilan box turtle is only found in Cuatro Ciénegas Basin (Coahuila, Mexico).[2]

Habitat

Because box turtles occupy a wide variety of habitats (which both vary on a day-to-day, season-to-season, but also species-to-species basis), a standard box turtle habitat cannot be identified. Mesic woodlands are a habitat where box turtles are generally found. T. ornata is the only species regularly found in grasslands, but its subspecies the desert box turtle is also found in the semidesert with rainfall predominantly in summer. The single location where Coahuilan box turtles are found is a 360 km2 region characterized by marshes, permanent presence of water and several types of cacti.

Prior to hibernation, box turtles tend to move further into the woods, where they dig a chamber for overwintering. Ornate box turtles dig chambers up to 50 centimeters, while eastern box turtles hibernate at depth of about 10 centimeters. The location for overwintering can be up to 0.5 km from the summer habitat and is often in close proximity to that of the previous year. In more southern locations, turtles are active year-round, as has been observed for T. coahuila and T. c. major. Other box turtles in higher temperatures are more active (T. c. yukatana) or only active during the wet seasons.[9]

Evolution

Box turtles appeared "abruptly in the fossil record, essentially in modern form". The absence of strong changes in their morphology might indicate that they are a generalist species.[4] It is therefore complicated to establish how their evolution from other turtles took place. The oldest finds of fossilized box turtles were found in Nebraska (U.S.), date from about 15 million years before present (in the Miocene)[4] and resemble the aquatic species T. coahuila most, which indicates that the common ancestor was also an aquatic species. Fossilized specimens of T. ornata and T. carolina were dated circa 5 million years before present and indicated that those main lineages also already diverged within the Miocene. The only recognized extinct subspecies (T. c. putnami) dates from the Pliocene and was, with a carapace length of 30 cm (12 in), much larger than other species.[4]

Interaction with humans

Conservation status

As the conservation status is defined for a species and not for a genus, differences exist between the different species in the genus Terrapene. Terrapene coahuila, as it is endemic only to Coahuila, is classified as endangered. While its geographic range reduced by 40% to 360 km2 in the past 40–50 years, the population of this species reduced from "well over 10,000" to "2,500" in 2002.[10] The most widely distributed species Terrapene carolina is classified as vulnerable, while Terrapene ornata is in a lower category as near threatened.[11][12] For Terrapene nelsoni insufficient information is available for classification.[13]

Sniffer dogs have been trained to find and track box turtles as part of conservation efforts.[14]

Box turtles as pets

Most turtle and tortoise societies recommend against box turtles as pets for small children.[15] Box turtles are easily stressed by over-handling and require more care than is generally thought. Box turtles get stressed when moved into new surroundings. Some specimens will wander aimlessly until they die trying to find their original home if they are removed from the exact area that they grew up in.[16] Three-toed box turtles are often considered the best ones to keep as pets since they are hardy and seem to suffer less from being moved into a new environment.

Box turtles can be injured by dogs and cats, so special care must be taken to protect them from household pets. Box turtles require an outdoor enclosure (although they can have indoor enclosures when necessary), consistent exposure to light and a varied diet. Without these, a turtle's growth can be stunted and its immune system weakened.

It is recommended to buy captive-bred box turtles (in areas where this is allowed) to reduce the pressure put on the wild populations. A 3-year study in Texas indicated that over 7,000 box turtles were taken from the wild for commercial trade. A similar study in Louisiana found that in a 41-month period, nearly 30,000 box turtles were taken from the wild for resale, many for export to Europe. Once captured, turtles are often kept in poor conditions where up to half of them die. Those living long enough to be sold may suffer from conditions such as malnutrition, dehydration, and infection.[17][18]

Indiana, Tennessee, and other states prohibit collecting wild turtles, and many states require a permit to keep them. Breeding is prohibited in some states for fear of its possible detrimental effects upon wild populations.[19]

Collecting box turtles from the wild may damage their populations, as these turtles have a low reproduction rate.[20]

State reptiles

North Carolina Secretary of State[21]

Box turtles are official state reptiles of four U.S. states. North Carolina and Tennessee honor the eastern box turtle.[22][23][24] Missouri names the three-toed box turtle.[25] Kansas honors the ornate box turtle.[26][27]

In Pennsylvania, the eastern box turtle made it through one house of the legislature, but failed to win final naming in 2009.[28] In Virginia, bills to honor the eastern box turtle failed in 1999 and then in 2009. In opposition one legislator had asked why Virginia would make an official emblem of an animal that retreats into its shell when frightened. What may have mattered most in Virginia, though, was the creature's close link to neighbor state North Carolina.[29][30]

Photos

Terrapene carolina carolina (young)

Terrapene carolina carolina (young) T. c. bauri hatchling

T. c. bauri hatchling Rings on the scutes of T. c. triunguis. Rings can be used to estimate the age of box turtles in their early years.

Rings on the scutes of T. c. triunguis. Rings can be used to estimate the age of box turtles in their early years. Florida box turtle in southeast Georgia

Florida box turtle in southeast Georgia

See also

References

- Rhodin 2010, pp. 000.106-107

- Fritz 2007, p. 196

- Blasius Merrem. "Versuch eines Systems der Amphibien" (PDF) (in German). Johann Christian Krieger. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- KDodd, pp. 24-30

- C.H. Ernst; R.G.M. Altenburg & R.W. Barbour. "Terrapene carolina". Netherlands Biodiversity Information Facility. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- KDodd, pp. 103-105

- KDodd, p. 140

- KDodd, pp. 114-116

- KDodd, p. 60

- van Dijk, P.P.; Flores-Villela, O. & Howeth, J. (2007). "Terrapene coahuila". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2007: e.T21642A97428806. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2007.RLTS.T21642A9304337.en.{{cite iucn}}: error: |doi= / |page= mismatch (help)

- Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group 1996 (1996). "Terrapene carolina". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group 1996 (1996). "Terrapene ornata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996. Retrieved 13 Feb 2011.

- Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group (1996). "Terrapene nelsoni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T21643A97298467. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T21643A9304626.en.{{cite iucn}}: error: |doi= / |page= mismatch (help)

- Ray, Julie (2011-07-31). "Service Dogs Find Endangered Species". Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- William Berg. "Boxturtles.com". Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- "Box Turtle Conservation | Box Turtles".

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-08. Retrieved 2007-06-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "TTN 1:19". Archived from the original on 2007-12-09. Retrieved 2007-06-19.

- http://www.in.gov/dnr/fishwild/3326.htm

- McCallum, M.L., J.L. McCallum, S.E. Trauth. 2009. Box turtles generally stay within the same area where they were born. If one is moved more than a half-mile from its territory, it may never find its way back. This may disrupt their breeding cycle. Predicted climate change may spark box turtle declines. Amphibia-Reptilia 30:259-264

- "Eastern Box Turtle – North Carolina State Reptiles". North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- Shearer 1994, p. 321

- "Official State Symbols of North Carolina". North Carolina State Library. State of North Carolina. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- "Tennessee Symbols And Honor" (PDF). Tennessee Blue Book: 526. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- "State Symbols of Missouri: State Reptile". Missouri Secretary of State Robin Carnihan. Retrieved 2011-01-21.

- Shearer 1994, p. 315

- "2009-73-1901 Kansas Code patriotic emblems, state reptile, designation". Justia. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- "Regular Session 2009–2010: House Bill 621". Pennsylvania State Legislature. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- "SB 1504 Eastern Box Turtle; designating as official state reptile". Virginia State Legislature. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- "Virginia House crushes box turtle's bid to be state reptile". NBC Washington. Associated Press. 2009-02-20. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- Bibliography

- Dodd Jr., C. Kenneth (2002). North American Box Turtles: A Natural History. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3501-4.

- Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World" (PDF). Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 149–368. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-01. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- Shearer, Benjamin F; Shearer, Barbara S (1994). "Miscellaneous Official State and Territory Designations". State Names, Seals, Flags, and Symbols: A Historical Guide, Revised and Expanded. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. pp. 167–326. ISBN 0-313-28862-3.

- Turtle Taxonomy Working Group [Rhodin; Anders G.J.; van Dijk, Peter Paul; Inverson, John B.; Shaffer, H. Bradley (2010-12-14). "Turtles of the World, 2010 Update: Annotated Checklist of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution and Conservation Status" (PDF). Chelonian Research Monographs. 5: 000.85–000.164. doi:10.3854/crm.5.000.checklist.v3.2010. ISBN 978-0965354097. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Terrapene. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Terrapene. |