Bonapartism

Bonapartism is the political ideology supervening from Napoleon Bonaparte and his followers and successors. The term was later used to refer to people who hoped to restore the House of Bonaparte and its style of government. In this sense, a Bonapartiste was a person who either actively participated in or advocated for conservative, monarchist and imperial political factions in 19th-century France. After Napoleon, the term was applied to the French politicians who seized power in the Coup of 18 Brumaire, ruling in the French Consulate and subsequently in the First and Second French Empires. The Bonapartistes desired an empire under the House of Bonaparte, the Corsican family of Napoleon Bonaparte (Napoleon I of France) and his nephew Louis (Napoleon III of France).[1]

2.svg.png.webp)

The term has been used more generally for a political movement that advocated a dictatorship or an authoritarian centralized state, with a strongman charismatic leader based on anti-elitist rhetoric, army support, and conservatism.

Marxism and Leninism developed a vocabulary of political terms that included Bonapartism, derived from their analysis of the career of Napoleon Bonaparte. Karl Marx was a student of Jacobinism and the French Revolution, and was a contemporary critic of the Second Republic and the Second Empire. He used "Bonapartism" to refer to a situation in which counter-revolutionary military officers seize power from revolutionaries, and use selective reforms to co-opt the radicalism of the popular classes. Marx argued that in the process, Bonapartists preserve and mask the power of a narrower ruling class.

More generally, "Bonapartism" may be used to describe the replacement of civilian leadership by military leadership within revolutionary movements or governments. Many modern-day Trotskyists and other leftists use the phrase "left Bonapartist" to describe those, such as Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong, who controlled 20th-century bureaucratic socialist regimes.

Noted political scientists and historians greatly differ on the definition and interpretation of Bonapartism. Sudhir Hazareesingh's book The Legend of Napoleon explores numerous interpretations of the term. He says that it refers to a "popular national leader confirmed by popular election, above party politics, promoting equality, progress, and social change, with a belief in religion as an adjunct to the State, a belief that the central authority can transform society and a belief in the 'nation' and its glory and a fundamental belief in national unity." Hazareesingh believes that although recent research shows Napoleon used forced conscription of French troops, some men must have fought believing in Napoleon's ideals. He says that to argue Bonapartism co-opted the masses is an example of the Marxist perspective of false consciousness: the idea that the masses can be manipulated by a few determined leaders in the pursuit of ends.

Ideology

Philosophically, Bonapartism was Napoleon's adaptation of the principles of the French Revolution to suit his imperial form of rule. Desires for public order, national glory, and emulation of the Roman Empire had combined to create a Caesarist coup d'etat for General Bonaparte on 18 Brumaire. Though he espoused adherence to revolutionary precedents, he "styled his direct and personal rule on the Old Regime monarchs."[2] For Bonapartists, the most significant lesson of the Revolution was that unity of government and the governed was paramount.

The honey bee was a prominent political emblem for both the First and Second Empires.[3] It represented the Bonapartist ideal of devoted service, self-sacrifice and social loyalty.[4]

The defining characteristics of political Bonapartism were flexibility and adaptability. Napoleon III once commented on the diversity of opinions in his cabinet, united under the banner of Bonapartism. Referring to the leading figures in the government of the Second Empire, he remarked: "The Empress is a Legitimist, Morny is an Orléanist, Prince Napoleon is a Republican, and I myself am a Socialist. There is only one Bonapartist, Persigny – and he is mad!"[5]

Origins

Bonapartism developed after Napoleon I was exiled to the island of Elba. The Bonapartists helped him regain power, leading to a period known as the Hundred Days. Some of his acolytes could not accept his defeat in 1815 at Waterloo or the Congress of Vienna, and continued to promote the Bonaparte ideology. After Napoleon I's death in exile on Saint Helena in 1821, many of these people transferred their allegiance to other members of his family. After the death of Napoleon's son, the Duke of Reichstadt (known to Bonapartists as Napoleon II), Bonapartist hopes rested on several different members of the family.[7]

The disturbances of 1848 gave hope to the nascent political undercurrent. Bonapartism, as an ideology of politically neutral French peasants and workers (EJ Hobsbawm), was essential in the election of Napoleon I's nephew Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte as President of the Second Republic, and gave him the political support necessary for his 1852 discarding of the constitution and proclaiming the Second Empire. Louis-Napoleon assumed the title Napoleon III to acknowledge the brief reign of Napoleon II at the end of the Hundred Days in 1815 (see the abdication of Napoleon I in 1815).

In 1870, the French National Assembly forced Napoleon III to sign a declaration of war against Prussia; France suffered a disastrous defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. The emperor surrendered to the Prussians and their German allies to avoid further bloodshed at the Battle of Sedan. He went into exile after a parliamentary coup created the Third Republic.[8]

Bonapartists continued to agitate for another member of the family to be placed on the throne. From 1871 forward, they competed with monarchist groups that favoured the restoration of the family of Louis-Philippe I, King of the French (1830–1848) (the Orléanists), and also with those who favoured the restoration of the House of Bourbon, the traditional French royal family (Legitimists). The strength of these three factions combined was powerful, but they did not unite on the choice of the new French monarch. Monarchist fervor eventually waned, and the French Republic became more or less a permanent facet of French life. Bonapartism was slowly relegated to being the civic faith of a few romantics as more of a hobby than a practical political philosophy. The death knell for Bonapartism was probably sounded when Eugène Bonaparte, the only son of Napoleon III, was killed in action while serving as a British Army officer in Zululand in 1879. Thereafter, Bonapartism ceased to be a significant political force.

The current head of the Bonaparte family is the great-great-great-grandson of Napoleon I's brother Jérôme, Jean-Christophe Napoléon (born 1986). There are no remaining descendants in the male line from any other of Napoleon's brothers and there is no serious political movement that aims to restore any of these men to the imperial throne of France.

Bonapartist claimants

Bonapartist Bonapartiste | |

|---|---|

| Leader | Adolphe Billault Charles de Morny Émile Ollivier Adolphe Vuitry Eugène Rouher Napoléon-Jérôme Bonaparte Georges-Eugène Haussmann |

| Founded | 1815 |

| Dissolved | 1889 |

| Ideology | Bonapartism |

| Political position | Center-right |

| Colours | Blue (early) Green (later) |

After becoming emperor in 1804, Napoleon I established a Law of Succession, providing that the Bonapartist claim to the throne should pass firstly to Napoleon's own legitimate male descendants through the male line. At that time he had no legitimate sons, and it seemed unlikely he would have any due to the age of his wife Joséphine. He eventually achieved an annulment, without Papal approval, of his marriage to Josephine. He married the younger Marie Louise, with whom he had one son.

The law of succession provided that if Napoleon's own direct line died out, the claim passed first to his older brother Joseph and his legitimate male descendants through the male line, then to his younger brother Louis and his legitimate male descendants through the male line. His other brothers, Lucien and Jérôme, and their descendants, were omitted from the succession (even though Lucien was older than Louis) because they had either politically opposed the Emperor or made marriages of which he disapproved. Napoleon abdicated in favor of his son after his defeat in 1815. Although the Bonapartes were deposed and the old Bourbon monarchy restored, Bonapartists recognized Napoleon's son as Napoleon II. A sickly child, he was virtually imprisoned in Austria, and died young and unmarried, without any descendants. When the French Empire was restored to power in 1852, the emperor was Napoleon III, Louis Bonaparte's only living legitimate son (their brother Joseph having died in 1844 without having had a legitimate son, only daughters).

In 1852, Napoleon III enacted a new decree on the succession. The claim was given to his own male legitimate descendants in the male line (though at that time he had no son, Louis later had a legitimate son, Eugène, who was recognized by Bonapartists as "Napoleon IV" before dying young and unmarried). If Napoleon III's line died out, he decreed that the claim should pass to Jérôme, Napoleon's youngest brother (who had previously been excluded), and his male descendants by Princess Catharina of Württemberg in the male line. (Excluded were his descendants by his first marriage, to the American commoner Elizabeth Patterson, of which Napoleon I had greatly disapproved.) The Bonapartist claimants since 1879, have been the descendants of Jérôme and Catherine of Württemberg in the male line.

The Bonapartist laws of succession were far from traditional. The family members ignored primogeniture (by excluding Lucien Bonaparte and his descendants); they annulled marriages to achieve their goals; and they did not submit to the Pope's rights as final arbiter on the validity of marriages. The very claim of the Bonaparte family to rule France was far from traditional.

List of Bonapartist claimants to the French throne since 1814

Those who ruled are indicated with an asterisk.

| Claimant | Portrait | Birth | Marriages | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Napoleon I* 1814–1815 |  | 15 August 1769, Ajaccio Son of Carlo Buonaparte and Letizia Ramolino | Joséphine de Beauharnais 9 March 1796 No children Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma 11 March 1810 1 child | 5 May 1821 Longwood, Saint Helena Aged 51 |

| Napoleon II* 1815–1832 |  | 20 March 1811, Paris Son of Napoleon I and Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma | Never married | 22 July 1832 Vienna Aged 21 |

| Joseph Bonaparte (Joseph I) 1832–1844 |  | 7 January 1768, Corte Son of Carlo Buonaparte and Letizia Ramolino | Julie Clary 1 August 1794 2 children | 28 July 1844 Florence Aged 76 |

| Louis Bonaparte (Louis I) 1844–1846 |  | 2 September 1778, Ajaccio Son of Carlo Buonaparte and Letizia Ramolino | Hortense de Beauharnais 4 January 1802 3 children | 25 July 1846 Livorno Aged 67 |

| Napoleon III* 1846–1873 President of France (1848–1852) Emperor of the French (1852–1870) |  | 20 April 1808, Paris Son of Louis Bonaparte and Hortense de Beauharnais | Eugénie de Montijo 30 January 1853 1 child | 9 January 1873 Chislehurst Aged 64 |

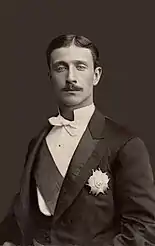

| Napoléon, Prince Imperial (Napoléon IV) 1873–1879 |  | 16 March 1856, Paris Son of Napoleon III and Eugénie de Montijo | Never married | 1 June 1879 Zulu Kingdom Aged 23 |

| Victor, Prince Napoléon (Napoléon V) 1879–1926 |  | 18 July 1862, Palais-Royal Son of Prince Napoléon Bonaparte and Princess Maria Clotilde of Savoy | Princess Clémentine of Belgium 10/14 November 1910 2 children | 3 May 1926 Brussels Aged 63 |

| Louis, Prince Napoléon (Napoléon VI) 1926–1997 | 23 January 1914, Brussels Son of Victor, Prince Napoléon and Princess Clémentine of Belgium | Alix, Princess Napoléon 16 August 1949 4 children | 3 May 1997 Prangins Aged 83 | |

| Charles, Prince Napoléon (Napoléon VII) 1997–present (disputed) | 19 October 1950, Boulogne-Billancourt Son of Louis, Prince Napoléon and Alix, Princess Napoléon | Princess Béatrice of Bourbon-Two Sicilies 19 December 1978 2 children Jeanne-Françoise Valliccioni 28 September 1996 1 child (adopted) | ||

| Jean-Christophe, Prince Napoléon (Napoléon VIII) 1997–present (disputed) |  | 11 July 1986, Saint-Raphaël, Var Son of Charles, Prince Napoléon and Princess Béatrice of Bourbon-Two Sicilies | Countess Olympia von und zu Arco-Zinneberg 17 October 2019 | |

The following are the list of Bonapartist claimants to the imperial throne.

- Napoleon I of France ruled from 1804 to 1815, abdicated in 1815 and died 1821.

- Napoleon, Duke of Reichstadt, son of Napoleon I, styled Napoleon II by Bonapartists. Briefly reigned as Emperor in France for a fortnight in June–July 1815 after his father's abdication following the defeat at Waterloo. After the deposition and exile of the Bonaparte family in July 1815, or at least from Napoleon I's death in 1821, he was Bonapartist claimant to the throne until 1832. He died in 1832 unmarried and with no children.

- Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon I's oldest brother, former King of Spain and claimant from 1832 to 1844. He died in 1844 with two daughters, but no legitimate male children.

- Louis Bonaparte, Napoleon I's second youngest brother, former King of Holland and claimant from 1844 to 1846. He died in 1846.

- Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, the only living legitimate child of Louis Bonaparte (though some have questioned whether he was Louis' biological son—his mother Hortense was notorious for her infidelity). He was President of France from 1849 to 1852 and under the name Napoleon III ruled as emperor from 1852 to 1870. He was claimant from 1846 to 1873. when he died,

- Napoléon, Prince Imperial, the only legitimate child of Napoleon III. He was claimant from 1873 to 1879. Styled Napoleon IV by his supporters, he died in 1879 unmarried and with no children.

- Napoléon Joseph Charles Paul Bonaparte, nicknamed Plon-plon, the only male child of Jérôme Bonaparte, Napoleon I's youngest brother, with Catharina of Württemberg (though Jerome had had another son earlier with Elizabeth Patterson). He was claimant from 1879 to 1891, but Eugene Bonaparte's will excluded him from the succession in favour of his son Napoleon Victor, leading to fierce disputes among the increasingly irrelevant Bonapartist circle. He died in 1891.

- Napoléon Victor Jérôme Frédéric Bonaparte, eldest son of Plon-plon and claimant from 1879 to 1926 (though many Bonapartists preferred his younger brother Louis). Until his father's death in 1891, he and his father both claimed the throne. He died in 1926.

- Louis Jerome Victor Emmanuel Leopold Marie Bonaparte, son of Napoleon Victor and claimant from 1926 to 1997. He died in 1997.

- Charles Marie Jérôme Victor Napoléon Bonaparte, the son of Napoleon Louis and claimant since 1997.

Electoral results

| Election year | No. of overall votes |

% of overall vote |

No. of overall seats won |

+/– | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chamber of Representatives | |||||

| May 1815 | Unknown (2nd) | Unknown | 80 / 630 |

||

| Chamber of Deputies | |||||

| 1815–1849 | Did not participate | Did not participate | 0 / 400 |

||

| Legislature | |||||

| 1852 | 5,218,602 (1st) | 86.5 | 253 / 263 |

||

| 1857 | 5,471,000 (1st) | 89.1 | 276 / 283 |

||

| 1863 | 5,355,000 (1st) | 74.2 | 251 / 283 |

||

| 1869 | 4,455,000 (1st) | 55.0 | 212 / 283 |

||

| National Assembly | |||||

| 1871 | Unknown (5th) | 3.1 | 20 / 630 |

||

| 1876 | 1,056,517 (3rd) | 14.3 | 76 / 533 |

||

| Chamber of Deputies | |||||

| 1877 | 1,617,464 (2nd) | 20.0 | 104 / 521 |

||

| 1881 | 610,422 (3rd) | 8.7 | 46 / 545 |

||

| 1885 | 888,104 (4th) | 11.2 | 65 / 584 |

||

| 1889 | 715,804 (5th) | 9.0 | 52 / 578 |

||

Marxism

Based on the career of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, Marxism and Leninism defined Bonapartism as a political expression.[9] Karl Marx was a student of Jacobinism and the French Revolution, as well as a contemporary critic of the Second Republic and Second Empire. He used the term Bonapartism to refer to a situation in which counterrevolutionary military officers seize power from revolutionaries, and use selective reformism to co-opt the radicalism of the masses. In the process, Marx argued, Bonapartists preserve and mask the power of a narrower ruling class. He believed that both Napoleon I and Napoleon III had corrupted revolutions in France in this way. Marx offered this definition of and analysis of Bonapartism in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, written in 1852. In this document, he drew attention to what he calls the phenomenon's repetitive history with one of his most quoted lines, typically condensed aphoristically as: "History repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce."[10][11]

Marx believed that a Bonapartist regime could exert great power, because there was no class with enough confidence or power to firmly establish its authority in its own name. A leader who appeared to stand above the class struggle could take the mantle of power. He believed that this was an inherently unstable situation, as the apparently all-powerful leader would be swept aside when the class struggle in society was resolved.

Leon Trotsky described Joseph Stalin's regime as Bonapartist, as he believed it was balanced between the proletariat, victorious but shattered by war, and the bourgeoisie, broken by the revolution but struggling to re-emerge. The failure of Stalin's regime to disintegrate under the shock and disruption of the losses of the Second World War, and the success of its expansion into Eastern Europe, challenged this analysis. Many Trotskyists rejected the idea that Stalin's regime was Bonapartist. Tony Cliff described such regimes as state capitalist in type and not as deformed workers' states at all. In the last year of his life, Trotsky argued the example of Napoleon's expanding empire. He had achieved the abolition of serfdom in Poland and other French holdings, but his empire was still "Bonapartist."

Bonapartism may be used generally to describe the replacement of civilian leadership by military leadership within revolutionary movements or governments. Some modern-day Trotskyists and others on the left use the phrase left Bonapartist to describe leaders such as Stalin and Mao Zedong, who controlled left-wing or populist totalitarian regimes. Bonapartism was an example of the Marxist idea of false consciousness: the masses could be manipulated by a few determined leaders in the pursuit of ends.

In the French political spectrum

According to historian René Rémond's famous 1954 book, Les Droites en France, Bonapartism constitutes one of the three French right-wing families; the latest one after far-right Legitimism and center-right Orléanism. According to him, both Boulangisme and Gaullism are considered to be forms of Bonapartism. However, this has been consistently disputed by Bonapartists and by many other historians. Notable examples of the latter include Vincent Cronin, who referred to Napoleonic government as "middle-of-the-road",[12] André Castelot in his Bonaparte, for whom being above and outside of party struggles was the founding principle of Bonapartism[13] and Louis Madelin, who describes Napoleon's role in French history as being the great reconciler after the divides and wounds of the French Revolution (conclusion to Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire).

In their own time, both Napoleon I and Napoleon III refused to be classed as either leftist or rightist, arguing that to claim to govern a country in the name of a faction meant acting against the national interest and one day succumbing to its influence. In Des Idées Napoléoniennes (On Napoleonic Ideas), published in 1839, the future Napoleon III quoted his uncle's words to the Council of State on this subject, ending with the following explanation:

"You see, this is why I have composed my Council of State of constituants who were called Moderates or Feuillants, like Defermon, Roederer, Regnier, Regnault; of royalists like Devaines and Dufresnes ; lastly of jacobins like Brune, Réal and Berlier. I like honest people of all parties". Prompt to reward recent services, as to shed luster all the great memories, Napoleon has placed in the Hôtel des Invalides, next to the statues of Hoche, of Joubert, of Marceau, of Dugommier, of Dampierre, the statue of Condé, the ashes of Turenne, and the heart of Vauban. He revives, in Orleans, the memory of Joan of Arc, in Beauvais that of Jeanne Hachette [...] Always faithful to principles of conciliation, the Emperor, during the course of his reign, gives a pension to the sister of Robespierre, as he does to the mother of the Duke of Orleans.

— Chapter III, p. 31

Bonapartists have consistently disagreed with this classification, as one of the fundamentals of Bonapartism as an ideology is the refusal to adhere to the left-right divide, which they see as an obstacle to the welfare and unity of the nation. Martin S Alexander, in his book "French History since Napoleon" (London, Arnold, New York, Oxford University Press, 1999) notes that Bonapartism as an idea would not have made a significant impact if it had been classifiable as either left-wing or right-wing. The historian Jean Sagnes in "The roots of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte's Socialism" notes that the future Emperor of the French edited his political works through far-left publishers.[14] Today, the Bonapartist philosophy would fit into the space occupied by the Parti Socialiste, the Mouvement Démocrate, the Nouveau Centre and the left wing of the conservative Union pour un Mouvement Populaire, as these parties occupy the ideological space between parties advocating class struggle and race-based politics, both of which are anathema to Bonapartists, as contrary to the ideal of national unity and religious and ethnic tolerance. This is demonstrated by Napoleonic policy towards industrial disputes, one expression of which – as Frank McLynn writes – is that strikes were forbidden by Napoleon I but in exchange the police sometimes prevented wages from being lowered,[15] while another is the assimilation and protection of the Jews.

The Marxist theory of "Left" and "Right" Bonapartism can be considered an illustration of what McLynn refers to as Napoleon I's appeal in equal measure "to both the Right and the Left",[16] and what Vincent Cronin describes as "middle of the way", or "moderate" government.[17] Napoleon III situated Bonapartism (or the "Napoleonic Idea") between the radicals and conservatives (respectively the Left and the Right) in "Des Idées Napoléoniennes", published in 1839. He expounded on this point to explain that Bonapartism, as practiced by his uncle Napoleon the Great (and represented by himself) was in the middle of "two hostile parties, one of which looks only to the past, and the other only to the future" and combined "the old forms" of the one and the "new principles" of the other.

While some French political parties are shaded by Bonapartism's political stance of national unity, since World War II, no major parties have advocated for Bonapartism in the sense of a return to the rule of a descendant of the Bonaparte dynasty.

Modern Bonapartism

In contemporary times, the term "Bonapartism" has been used in a general sense to describe autocratic, highly centralized regimes dominated by the military.[18]

Other Bonapartists

In 1976, when Jean-Bédel Bokassa, a great admirer of Napoleon, made himself Emperor Bokassa I of Central Africa, he declared that the ideology of his regime was Bonapartism and added golden bees to his imperial standard.

Raymond Hinnebusch has characterized Hafez al-Assad's regime in Syria as Bonapartist.

See also

References

- Hanotaux, Gabriel (1907). Contemporary France. Books for Libraries Press. p. 460.

- Truesdell, Matthew (1997). Spectacular Politics: Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte and the Fête impériale, 1849-1870. Oxford University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-19-510689-3. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- "History of the Two Empires: The Symbols of Empire". Fondation Napoléon. 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- Englund, Steven (2005). Napoleon: A Political Life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-674-01803-7. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- Jerrold, Blanchard (1882). The Life of Napoleon III. London: Longmans, Green. p. 378. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- Lindsay, Suzanne G. (2012), Funerary Arts and Tomb Cult: Living with the Dead in France, 1750-1870, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., p. 172 (footnote 16), ISBN 978-1-4094-2261-7

- Riff, Michael A. (1990). Dictionary of Modern Political Ideologies. Manchester University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7190-3289-9. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- Acton, Lord (1909). The Cambridge Modern History. New York: Macmillan Co. p. 495ff. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- , Marxists website

- Marx, Karl (1973). David Fernbach (ed.). Surveys in Exile. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-14-021603-5.

Hegel remarks somewhere that all great events and characters of world history occur, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.

- Marx, Karl (1963). The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. New York: International Publishers. pp. 15. ISBN 0-7178-0056-3.

- Croin, Vincent (1994 ed.). Napoleon. HarperCollins. ch. 15. p. 229.

- Castelot, André (ed. 1967). Perrin. ch. VIII. p. 240.

- Jean Sagnes (2006). Les racines du socialisme de Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte. Toulouse: Privat.

- McLynn (1998), p. 482.

- McLynn (1998), p. 667.

- Vincent Cronin (1994). "Chapter 19". Napoleon. HarperCollins. p. 301.

- Calhoun, Craig J. (2002). Dictionary of the Social Sciences. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-19-512371-5. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

Bibliography

Bluche, Frédéric (1980). Le bonapartisme: aux origines de la droite autoritaire (1800-1850). Nouvelles Editions Latines. ISBN 978-2-7233-0104-6.

Further reading

- Alexander, Robert S. Bonapartism and revolutionary Tradition in France: the Fédérés of 1815 (Cambridge University Press, 2002)

- Baehr, Peter R., and Melvin Richter, eds. Dictatorship in history and theory: Bonapartism, Caesarism, and totalitarianism (Cambridge University Press, 2004)

- Dulffer, Jost. "Bonapartism, Fascism and National Socialism." Journal of Contemporary History (1976): 109-128. In JSTOR

- McLynn, Frank (1998). Napoleon. Pimlico.

- Mitchell, Allan. "Bonapartism as a model for Bismarckian politics." Journal of Modern History (1977): 181-199. In JSTOR

- Bluche, Frédéric, Le Bonapartisme, collection Que sais-je ?, Paris, Presses universitaires de France, 1981.

- Choisel, Francis, Bonapartisme et gaullisme, Paris, Albatros, 1987.