Beit Ghazaleh

Beit Ghazaleh (The Ġazaleh House; Arabic: غزالة) is one of the largest and better-preserved palaces from the Ottoman period in Aleppo. It was named after the Ghazaleh[1][2] family that owned it for about two centuries.[3][4] Since 1914, it was used as a public school[5] and was recently restored to host the Memory Museum of the city of Aleppo. Beit Ghazaleh is located in the Al-Jdayde district of Aleppo.[6][7]

| Beit Ghazaleh | |

|---|---|

| Native name Arabic: غزالة | |

The central courtyard of Beit Ghazaleh | |

| Location | Aleppo, Syria |

| Coordinates | 36°12′24.4″N 37°09′23.1″E |

| Area | Al-Jdayde, Aleppo |

| Built | 17th century |

| Architectural style(s) | Syrian-Ottoman |

| Governing body | Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums |

Location of Beit Ghazaleh in Aleppo | |

History: the origins of the Ġazaleh House in Aleppo

The house is located on the Western edge of a large suburb inhabited by a multi-religious and multi-ethnic population. This neighbourhood to the North of the old city of Aleppo developed since the late Mameluke period. This area became the Christian quarter of Jdeideh which was organically clustered around its churches. Here lived the notables of Aleppo's Christian communities, notably the Armenians who specialised in trade with India and Persia.[4]

The Ġazaleh House was built in front of two large Muslim waqfs — created in 1583-90 and 1653 — and together they form the monumental heart of a lively mixed Christian-Muslim neighbourhood.[8] Unique for its size and decor, Beit Ghazaleh embodies the wealth and power of the Christian community in 17th century Aleppo. The decorative panels of Beit Ghazaleh do not include human figure representations; made by local craftsmen, the panels display many painted inscriptions presenting a mix of popular sayings, mystic poetry[9] and biblical psalms. This diversity of sources underlines the rich Arab culture and the eclecticism typical of Aleppo urban élites.

A palace built around many courtyards

Throughout the centuries, the mansion's footprint expanded or contracted according to changing needs and fortunes. However, it always maintained a main central courtyard of 250m2. At its apex, the house covered an area of approximately 1,600m2, with 570m2 occupied by six courtyards. The actual size of the complex is practically invisible from the outside.

The present entrance was opened in the 19th century on the main street on the house’s East side. This entrance leads to the principal courtyard, the focal centre and the main thoroughfare to the rest of the house. Polychrome marble tiles, forming a "carpet" in front of the iwan, precede the great fountain in the courtyard, with its games of water, stone basins and cascades. The fine wall decorations in the courtyard are said to have been carved by the Armenian sculptor Khachadur Bali a member of the Balyan family of Ottoman court architects.[10]

The iwan

A North-South axis cuts through the whole house underlining the importance of the iwan from where it originates. This line divides the courtyard's paving, basin and garden into a precise geometry. The rest of the space is organized according to the needs of the household and the shape of the plot without concern for symmetry.

All around the main courtyard, windows and doors punctuate the facades. Above these openings, the relative intricacy of the low relief decor surrounding them establishes the hierarchy of the rooms with the iwan at its summit. The stone decor of the iwan facade and of its annexes likely dates from the mid-17th century. The painted wooden panels of the qubba[11] and the surviving panels of the iwan are likely dated from the same period. The iwan, first meant to provide comfort from the summer heat,[12] is thus the "centre" of the house and plays an essential symbolic role representing the power of the master of Beit Ghazaleh.

Rooms around the central courtyard

The five rectangular rooms accessible from the courtyard were once decorated with woodwork that has now almost entirely disappeared. The sixth room to the West is a vast T-shaped qa'a,[13] indicative of wealth and power.

The North facade

Opposite the iwan, the North façade dates from the end of the 17th century. It is remarkable for its lavish decor, unique in Aleppo. In the centre, the ablaq[14] emphasizes the strict symmetry of the facade, while the interior spaces do not follow the same organization. According to an inscription, the large room in the East Wing dates from 1691. Its rich interior decoration, partially refurbished in the 19th century, includes four distinct sets of inscriptions:

- Psalm 91[15] of the Bible on the ceiling cornice;

- Popular sayings on the cornice of the wooden panelling;

- The fifteen transom panels above the openings reproduce a poem by Abû al-Fath al-Bustî[16] addressing the themes of the condemnation of excess and unnecessary, reflections on human relationships, the need for God's help, and the need to be in control of one's body and improve one's heart and mind;

- The inscriptions above the niches on the North side reproduce the verses of al-Mutanabbi on honour, wisdom and ignorance.

The floors

The floor of the iwan, and of some other rooms, has retained its old split-level organization. The spaces where you stand and circulate, the corridors and the ataba-s,[17] are roughly at the same level as the courtyard. The rest of each room, covered with mats and rugs, is about 50 centimetres higher. The line of sight and the height of cushions determine the height of the sills and windows and thus the internal and external organization of the facades.

The hammam

The hammam steam bath in the northwest corner is comparable to a public bath, but presents a simplified plan because the vast 'qâ‘a' served as a dressing room and resting space before and after bathing.

Kitchens and other service quarters, stables, granaries and warehouses for provisions were likely situated to the North-east and South of the house, accessible from the alleys that surround the plot to the house's North and the South.

The West wing (the Qâ‘a)

The southwest corner of the courtyard, and the West wing, was completely rebuilt in 1737. It includes three key elements: a very large rectangular room with a fireplace, a large 'qâ‘a' and a hammam. The T-shaped 'qâ‘a' includes three iwan-s with wooden ceilings framing a ataba with a small octagonal basin in the centre, covered with a dome. The fourth facade of the ataba opens towards the central courtyard. Its interior decor includes stone tiles with geometric patterns and wooden panels painted with cups and fruit bouquets in vases.[18]

The 'qâ‘a' has two sets of inscriptions. The poem calligraphy on transoms (in praise of the Master of the House) begins with a discourse on wine. It ends with a dedication and the name of Jirjis along with a date of 1737. Inscriptions on the ceilings offer praise to the Virgin and include a poem of love typical of Sufi mystic texts.

The 19th century additions

Significant changes were made to Beit Ghazaleh during the nineteenth century. Notably, rooms were added on the top of the North wing (dated 1880 by an inscription). A new Southern entrance to the impasse Chtammâ was built, dated 1304/1887. These major redevelopments were inspired by the appearance of consular apartments in the Aleppo urban caravanserais[19] and by the architecture of embassies in the capital Istanbul.

Loss, looting and destruction

During the nineteenth century, changes in the domestic lifestyle and the introduction of Western furniture ultimately led to aristocratic families abandoning houses such as Beit Ghazaleh. The transformation of the Ghazaleh House into a school was a factor for both its destruction and its preservation. While it allowed the preservation of the physical structure of the building, it also favoured the "disappearance" of a great deal of its decoration.[18][20]

Sections of the house's exceptional wooden decorative panels were still in place prior to the Syrian civil war. By the time of its restoration in 2011, a number of pieces had been lost, dismembered or sold to individuals or to museums.[21]

Since then the Ghazaleh house, especially its iwan, suffered catastrophic damage during the Syrian civil war. The property was effected by various explosions from house-to-house combat. Prior to this, all the remaining wooden decorative panels, with the exception of a few ceilings, were also removed (now confirmed looted).[22][23][24]

A file regarding the looting of the decorative panels was submitted "to Interpol and the International Council of Museums in the hope that the panels resurface on the art market and can be returned" to the museum.[25]

Recent studies and restoration works

From 2007 to 2011, the Syrian Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums (DGAM) conducted a major campaign of restoration to transform Beit Ghazaleh into a museum dedicated to the memory of the city of Aleppo. Restoration work notably concerned the renovation of part of the decorative panels by Damascene craftsmen.

In parallel, descendants of the Ghazaleh family[26][27] launched a scientific study of the House. This study, which began in 2009, includes a historical research on the neighbourhood and of the house, a stylistic analysis of its decorative elements, and a detailed architectural survey. The study aimed to establish a precise chronology of Beit Ghazaleh's evolution since its inception.[28]

A collaborative high precision survey of Beit Ghazaleh was completed in November 2017 by the DGAM and UNESCO to facilitate the further study, protection and emergency consolidation of its structure.[29][30] Further reports have been issued regarding damage to the property and looting of its decorative panels.[24][31]

Sources and further reading

- Sauvaget, Jean (1941) Alep. essai sur le développement d'une grande ville syrienne, des origines au milieu du XIXe siècle. Paris, Librairie orientaliste Paul Geuthner, texte et album.

- David, Jean-Claude et François Cristofoli (2019) Alep, la maison Ghazalé. Histoire et devenirs. Editions Parentheses, 176 p. ISBN 978-2-86364-323-5

- David, Jean-Claude (2018) La guerre d’Alep 2012-2016. Destruction de la maison Ghazalé (1/2), ArchéOrient - Le Blog, 9 mars 2018; David, Jean-Claude (1982) Le waqf d'Ipchir Pacha à Alep (1063/1653), étude d'urbanisme historique. IFPO Damas, collection PIFD.

- Collectif 1989, (1989) L’habitat traditionnel dans les pays musulmans autour de la Méditerranée, I. L’héritage architectural: formes et fonctions, Le Caire, IFAO.

- RC Heritage (2011–15) Beit Ghazaleh (maison du XVIIè s.) à Alep [ Syrie ] étude historique et architecturale | historical and architectural analysis [working document]

- Publications mentioning the Ġazaleh House and family : David Jean-Claude, Degeorge Gérard (2009) Palais et demeures d'Orient - XVIe-XIXe siècle, Actes Sud / Imprimerie Nationale; Al-Homsi Fayez (1983) Old Aleppo, Damascus: Ministry of Culture and National Heritage Publishing, p. 127-128, Mansel Philip (2016) Aleppo Rise and Fall of Syria's Great Merchant City, IB Tauris, pp. 28–29, 44, 6pl; Masters, Bruce (1999) Aleppo: the Ottoman Empire's caravan city, in Edham, E., Goffman, D. and Masters, B., The Ottoman City between East and West: Aleppo, Izmir, and Istanbul. New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 58; Julia Gonnella (1996) Ein christlich-orientalisches Wohnhaus des 17. Jahrhunderts aus Aleppo (Syrien). Das 'Aleppo-Zimmer' im Museum für Islamische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Mainz: P. von Zabern, pp. 76; Dorothea Duda (1971) Innenarchitektur syrischer Stadthäuser des 16. bis 18. Jahrhunderts. Die Sammlung Henri Pharaon in Beirut (Beiruter Texte und Studien, 12) Wiesbaden (Steiner); Fedden, Robin (1956) Syria: a historical appreciation. London, Hale. p. 36; Samné, George (1928) Le Process Gazale : Correspondance d'Orient : revue économique, politique & littéraire / directeurs: Bibliothèque nationale de France (gallica.bnf.fr): [s.n.] pp. 241–5.

- Photographic archives: Aga Khan Trust for Culture and the Aga Khan Documentation Center at MIT, Bayt Ghazala ; MIT Libraries, Ghazale House ; Aga Khan Visual Archive, Ghazala House ; Photographs from Brandhorst & Bremer, 2001.

- Since 2011 numerous initiatives have been launched to protect Aleppo's unique heritage. Those that specifically mention the Ġazaleh House include: Safeguarding Syrian Cultural Heritage (programme UNESCO), Blue Shield International; Heritage For Peace, Protection of Cultural Heritage During Armed Conflict, The Aleppo No Strike List.

Gallery

Stonework on the north facade of the Ġazaleh House

Stonework on the north facade of the Ġazaleh House The central courtyard of Beit Ghazaleh (2010)

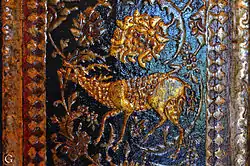

The central courtyard of Beit Ghazaleh (2010) The 'Gazelles' of the Ġazaleh House, panels as seen in the Pharaon Collection (Mouwad Museum) of Beyrouth in 2011.

The 'Gazelles' of the Ġazaleh House, panels as seen in the Pharaon Collection (Mouwad Museum) of Beyrouth in 2011. The courtyard of Beit Ghazaleh (December 2016)

The courtyard of Beit Ghazaleh (December 2016) The qoubba's wooden panels of the Ġazaleh House (now missing)

The qoubba's wooden panels of the Ġazaleh House (now missing) The entrance of Beit Ghazaleh in Aleppo's Al-Jdayde district (2010)

The entrance of Beit Ghazaleh in Aleppo's Al-Jdayde district (2010) Beit Ghazaleh Qa'a -- its fine decorations were looted before the building was hit by multiple explosions (2017)

Beit Ghazaleh Qa'a -- its fine decorations were looted before the building was hit by multiple explosions (2017)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beit Ghazaleh. |

References

- According to the transcripts and genealogical lines of the family, the name can be found spelt in different ways: Gazalé, Ġazaleh, Gazale, Ghazaleh. The Ghazaleh were prominent Aleppine merchant bankers and traders.

- Samné, George (1928). Le Process Gazale : Correspondance d'Orient : revue économique, politique & littéraire / directeurs :. Bibliothèque nationale de France (gallica.bnf.fr). pp. 241–5.

- The oldest parts of the house are at least 350 years old.

- Jean-Claude David (2018-03-09). "La guerre d'Alep 2012-2016. Destruction de la maison Ghazalé (1/2)". ArchéOrient - Le Blog (in French). Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- It was first converted into a German and then an Armenian school (Haigazian Varjaran).

- Transliteration. The neighbourhood has been recorded as Al-Jdaydeh, Al-Jdeideh, Al-Judayde, Al-Jdeïdé, Al-Judayda, from the Arabic جديدة.

- "iDAI.gazetteer | Bayt Ghazala". gazetteer.dainst.org. Retrieved 2019-01-24.

- See Jdayde's Waqf of Ibshir Mustafa Pasha for further information.

- Their authors were either Muslim or Christian.

- Michael D. Danti, Allison Cuneo, Susan Penacho, Amr Al-Azm, Bijan Rouhani, Marina Gabriel, Kyra Kaercher, Jamie O’Connell (17 August 2016). "ASOR CHI Weekly Report 107" (PDF). asor-syrianheritage.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- This Arabic term generally designates a dome which may indicate a funereal function. In the local arab architecture of the Near East (Syria) an iwan is almost always built between two quabba (qubbatayn) the access to which is generally regulated by the iwan and therefore are like "alcoves" (ai-qubba). They can be covered by a cupola or a wood ceiling.

- The iwan is rather an airy space for the cool early hours of summer days or sunny periods during the winter and are open to the north in Syria.

- In domestic arab architecture (notably in Syria and Egypt), this term designates a principal room, by its dimensions, the richness of its decor and its relative importance in the building. This room is generally multifunctional and often centrally located and remarkable by the extent of its architecture.

- Polychrome elements presented in horizontal bands

- Often quoted to express confidence in God the protector

- Notable Arabian poet. See this reference for further information

- The term gives the idea of entrance, of transitions and of the edge of a room and its rather specific Syrian use (durqa’a in Egypt). The atabe is mainly characterised by the low level of its floor close to that of the exterior of the room and about forty centimetres lower than that of the room. One can stand upright and deposit ones shoes before getting installed on the ground at the upper part of the room.

- Duda, Dorothea (1971). "Innenarchitektur syrischer Stadthäuser des 16. bis 18. Jahrhunderts". www.perspectivia.net. FRANZ STEINER VERLAG. pp. 35, 90–1, 108. Retrieved 2018-02-27.

- For further information please see the entry for the Al-Madina Souq of Aleppo

- TARAZI, Camille INGEA, Tania (2015) Vitrine de l’Orient : Maison Tarazi, fondée à Beyrouth en 1862, Beyrouth:DE LA REVUE PHENICIENNE , p.202; see also Ghazaleh House panels in the collection of the Robert Mouwad Museum in Beyrouth

- UNESCO (2014) Safeguarding Syrian Cultural Heritage/Ghazaleh House, Accessed via http://www.unesco.org/new/en/safeguarding-syrian-cultural-heritage/ghazaleh-house on 15 August 2014.

- "Photos of Damage of Traditional Art Museum, Dar Ghazaleh, and Jdaideh in old Aleppo المديرية العامة للآثار والمتاحف". www.dgam.gov.sy. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- "A house dismantled - Beit Ghazaleh, the house of the Ġazaleh, غزالة". art-crime.blogspot.co.uk (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- Alaa Haddad, Issam Ballouz, Rami Alafandi (September 2018). "Bayt Ghazala | بيت غزالة | Report about missing ʿAjami wooden panels from Bayt Ghazala (Aleppo) | تقرير حول فقدان خشبيات العجمي في بيت غزالة (حلب)" (PDF). L.I.S.A. WISSENSCHAFTSPORTAL GERDA HENKEL STIFTUNG (in German). Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 2019-01-24.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Danielle. "Berlin's Pergamon museum reveals new exhibit for preservation of Syria's war-torn heritage". Retrieved 2019-12-29.

- Vogue. "An Ode To Syria". British Vogue. Retrieved 2017-06-07.

- Chekri-Ganem, Dr Georges Samné (1928). Le Process Gazale. Paris: Correspondance d'Orient : revue économique, politique & littéraire.

- RC Heritage (2011–2017). "Beit Ghazaleh (maison du XVIIè s.) à Alep [ Syrie ] étude historique et architecturale | historical and architectural analysis". Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- Art Graphique & Patrimoine (2017-11-28), Relevé et nuage de points de Beit Ghazaleh, Alep - Syrie (mission UNESCO), retrieved 2018-10-09

- Art Graphique & Patrimoine. "Bruno Deslandes (Director International & Heritage at risk in Art Graphique & Patrimoine) at BBC World TV to speak about reconstruction process currently ongoing in Aleppo (Syria)". fr-fr.facebook.com (in French). Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- United Nations Institute for Training and Research (2018). "FIVE YEARS OF CONFLICT The State of Cultural Heritage in the Ancient City of Aleppo". unesdoc.unesco.org. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved 2019-01-10. Alt URL Archived 2018-12-17 at the Wayback Machine