Beaver Hills (Alberta)

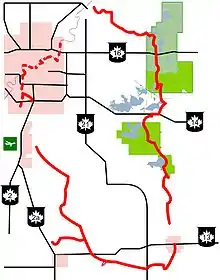

The Beaver Hills (Cree: Amiskwaciy, lit. 'beaver hills'), also known as the Beaver Hills Moraine and the Cooking Lake Moraine, are a rolling upland region in Central Alberta, just to the east of Edmonton, the provincial capital. It consists of 1,572 square kilometres (607 sq mi) of "knob and kettle" terrain, containing many glacial moraines and depressions filled with small lakes. The major lakes were connected til Camrose reverse drained their headwaters, Miquelon. The landform lies partly within five different counties, Strathcona, Leduc, Beaver, Lamont and Camrose. The area is relatively undeveloped compared to the surrounding region, and is protected by in part by Elk Island National Park, the Cooking Lake–Blackfoot Provincial Recreation Area, the Ministik Bird Sanctuary, Miquelon Lake Provincial Park and a number of smaller provincial natural areas.[1]

Natural history

The "hills" are very low and not very prominent, as the region is actually just a slight rise above the surrounding region which also happens to be rough and rolling due to a different history during the end of the last ice age. Being at a slightly higher elevation, the bedrock in what would become the hills only briefly covered by glacial Lake Edmonton, which deposited a thick layer of silt on the rest of the region, the basis of the modern agricultural soils now found in the areas around the hills, but left mostly gravel and boulder-sized debris on the hills, along with much water in the depressions left behind by ice and stone during the preceding glacial era.[2]

The vegetation is typically of part of the dry mixedwood boreal forest natural subregion, a transitional zone on the south edge of the boreal forest, but is surrounded by aspen parkland. This island of boreal forest in the south means that both boreal animal species (moose, black bear, Canada lynx) and grassland animal species (sharp-tailed grouse, mule deer) live in the region.[1] Nearby landscapes include Beaverhill Lake just to the east, and the North Saskatchewan River to the north.

Human history

Indigenous peoples and fur trade history

As a well wooded and watered area near to more open grasslands, the Beaver Hills were an important camping place for nomadic peoples making a seasonal migration between the plains and the hills. It was a place that Indigenous people "could replenish and recoup after spending extended periods on the plains, a place where they could hunt, fish, and gather other needed resources".[3] Because the hills were not ploughed under, unlike the rest of region, much archaeological evidence remains here, including 227 Native sites recorded by Parks Canada in Elk Island Park alone.

The Sarcee are the first ethnic group known to have inhabited the region in the period after European contact (and thus the beginning of a written historical record). Sometime before 1800 Cree people migrating from the east displaced the Sacree from the hills onto the plains. The Cree called the region Amiskwaciy, which literally means "beaver hills" and is the origin of the region's later names in French, and then English.[4] The Cree pursued an economy based around trapping and trading with Euro-Canadian fur companies as well as the more traditional forms of hunting gathering, and fishing. The Cree also adopted buffalo hunting techniques from plains peoples to the south, including the use of buffalo pounds. The beaver and other game species in the area eventually became trapped out, and they largely abandoned the area as a permanent home, though continued to travel through the area.

Two major Indigenous and fur trade trails border the hills, the Victoria Trail to the north and the Battle River Trail to the south. The Beaver Hills are mentioned in Euro-Canadian records as early as Peter Fidler's sketches of 1793. David Thompson's map of 1814 mentions the hills prominently as place of refuge for both the Sarcee and Cree. They are also reported on by the Palliser Expedition of the 1850s and by Joseph B. Tyrell of the Geological Survey of Canada in the 1880s.[5]

Initial reserve development

This is one of oldest protected areas in Canada, having originally been a forest reserve set aside by the federal Department of the Interior in 1892, during the homesteading era. It was formalized as the Cooking Lake Forest Reserve in 1899, the first such reserve in Canada.[6] A part of the reserve was given further protection in 1906 as Elk Park, later to become Elk Island National Park. In 1930, Crown lands in Alberta passed from the federal government to the provincial government, Elk Park became formalized as a national park while the rest of the Cooking Lake Forest Reserve became a provincial responsibility.[6][7]

Later development

In 2002 the Beaver Hills Initiative was created to coordinate land-use planning in the municipalities in the area surrounding the protected parks. This resulted in a scheme of tradable development credits.[8] In 2006 the area became recognized as a dark sky preserve by the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada.[9] In 2016 it was named a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.[10]

See also

References

- "Ecological Primer – What Makes the Beaver Hills So Special?" (PDF). Beaver Hills Initiative. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 19, 2011. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- Macdonald, pp. 9-12

- http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/canadian_historical_review/summary/v092/92.2.fortna.html

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2014-01-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- MacDonald, pp. 1-9

- "History". Do The Blackfoot. Archived from the original on February 5, 2011. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- "The Chronology of Elk Island National Park". Parks Canada. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- "Who we are". Beaver Hills Initiative. Archived from the original on February 19, 2011. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- "Beaver Hills Dark Sky Preserve". Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. Archived from the original on 22 December 2010. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- "Two Canadian sites join UNESCO biosphere network". CTV News. 21 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.