Aspen parkland

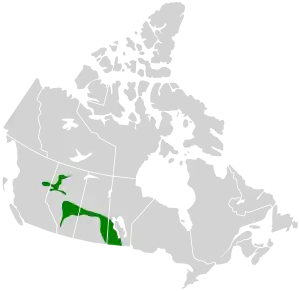

Aspen parkland refers to a very large area of transitional biome between prairie and boreal forest in two sections, namely the Peace River Country of northwestern Alberta crossing the border into British Columbia, and a much larger area stretching from central Alberta, all across central Saskatchewan to south central Manitoba and continuing into small parts of the US states of Minnesota and North Dakota. [3] Aspen parkland consists of groves of aspen poplars and spruce interspersed with areas of prairie grasslands, also intersected by large stream and river valleys lined with aspen-spruce forests and dense shrubbery. This is the largest boreal-grassland transition zone in the world and is a zone of constant competition and tension as prairie and woodlands struggle to overtake each other within the parkland.[4]

| Aspen parkland | |

|---|---|

| |

Aspen parkland within Canada | |

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Nearctic |

| Biome | Temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands |

| Borders | List

|

| Bird species | 206[1] |

| Mammal species | 72[1] |

| Geography | |

| Area | 397,304 km2 (153,400 sq mi) |

| Countries | Canada and United States |

| States/Provinces | British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, North Dakota and Minnesota |

| Conservation | |

| Conservation status | Critical/Endangered[2] |

| Habitat loss | 63.76%[1] |

| Protected | 2.95%[1] |

This article focuses on this biome in North America. Similar biomes also exist in Russia north of the steppes (forest steppe) and in northern Canada.

Definitions

According to the Ecological Framework of Canada, published in 1999, the Aspen Parkland ecoregion (#156) is the largest and northernmost section of Prairies Ecozone.[5] This definition is the arc-shaped region (i.e. including the WWF's central and foothills parkland but excluding the Peace River region). Partly defined by climate, it had a mean annual temperature of approximately 1.5 °C circa 1999, and rainfall varied from 400–500 mm/annum. It includes the communities of Red Deer and Edmonton in Alberta; Lloydminster on the Alberta–Saskatchewan border; North Battleford, Saskatoon, Humboldt, and Yorkton in Saskatchewan; and Brandon, Manitoba as its major population centres and have a total population of 1.689 million. By this definition, there are approximately 5,500,000 hectares (14,000,000 acres) of this ecoregion in the province of Alberta.[6]

According to the World Wide Fund for Nature the Canadian Aspen forests and parklands (NA0802) encompass eight ecoregions as used in the Ecological Framework of Canada: the Peace Lowland, Western Boreal, Boreal Transition, Interlake Plain, Aspen Parkland, and Southwest Manitoba Uplands (TEC 138, 143, 149, 155, 156, 161, 163, and 164). These ecoregions lie in both the Boreal Plains Ecozone and the Prairies Ecozone (Ecological Stratification Working Group 1995). The Boreal sections are Manitoba Lowlands, Aspen-Oak, Aspen Grove, Mixedwood, and Lower Foothills (15-17, 18a and 19a).[7]

Setting

The aspen parkland biome runs in a thin band no wider than 500 km through the Prairie Provinces, although it gets broader to the west, especially in Alberta. This is a hilly landscape with many small lakes and ponds. The cities of Edmonton and Saskatoon are the largest cities completely in this biome while Winnipeg is bordered by tallgrass prairie to the west and south and the aspen parkland to the northeast, and Calgary is bordered by prairie to the east and the Foothills Parkland to the west.

There are three main sections of aspen parkland: Peace River, Central, and Foothills. The Central Parkland is the largest section and is part of main band of aspen parkland extending across Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, bordered by prairie to the south and the boreal forest to the north. The Peace River Country is located along the Peace River region of the province, extending across the border into northeastern British Columbia, and is completely surrounded by boreal forest, cutting it off from the Central Parkland, it extends as far north as Fort Vermilion at 58°N 116°W. The Foothills parkland covers the Foothills of the Rocky Mountains as far south as Waterton Lakes National Park.[8][9]

Climate

The region has a Humid continental climate accompanied by a subhumid low boreal transitional grassland ecoclimate.[2] Summers are warm and short and winters can be long and cold. The Mean annual temperatures range from 0.5 to 2.5 °C (32.9 to 36.5 °F), with Summers ranging 13 to 16 °C (55 to 61 °F), and winters ranging −14.5 to −12.5 °C (5.9 to 9.5 °F). The Peace River Country in northwestern Alberta and northeastern areas of the North Interior in British Columbia has the coolest climate, but still supports extensive farmland. Southwest Manitoba sees the warmest. Annual precipitation is usually between 375 to 700 millimetres (14.8 to 27.6 in).[2] Chinook winds off the foothills also occur in winter, mainly affecting Alberta.

Flora

Four significantly different habitats are common in the aspen parklands: The fescue prairie, the woodlands, the ravines and the wetlands and lakes. A rarer habitat type, tallgrass aspen parkland, occurs only in the extreme southeastern corner of the aspen parklands biome (southeastern Manitoba/northwestern Minnesota). The fescue prairie is a meadowland rich in vegetation variety which forms the cover for the development of the richer soils that underlie the parklands. The close association with woodlands and wetlands makes this a choice location for many plants and a preferred range or home site for a wide diversity of wildlife. The richer soil and increased precipitation favours the natural growth of fescue grass, but varying conditions such as moisture level and grazing pressures allow for the invasion of secondary plant species.

There are numerous grasses and sedges in the fescue prairie. Gravelly and rocky terrain is a good location for parry oat grass. Dry areas favour June, porcupine and spear grass. Wet areas are often covered with slender wheat grass and timber oat grass. Prairie rose and snowberry are common shrubs found in these grasslands.

The forested, or woodlands area is dominated by trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides), balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera), other poplars and spruces, although other species of trees do occur. Pines, mostly jack pine and lodgepole pine will often grow in areas that have sandy soil conditions. Other native species may include box elder, tamarack and willow, while the foothills area in the southeast of the region, such as Turtle Mountain or Spruce Woods Provincial Park, have woodland of white spruce and balsam fir but quaking aspen will dominate where the woodland has been cleared by fire. The proportion of forests to grasslands has increased somewhat over the prairie in areas not affected by agriculture in the last 100 years. This increase is partly due to the reduction of prairie fires which used to destroy the new saplings on the fringes of the aspen groves. Also, it was a common practice for farmers to plant stands of trees as windbreaks.

Aspen woodlands support an extensive understory consisting of mid-sized and small shrubs, some herbs and ground cover. Spruce-dominated woodlands usually do not support a dense understory due to more acidic and nutrient-poor soils and a denser canopy, which reduces sunlight reaching the forest floor below. However, in areas where a mixture of aspen and spruce occur, a fairly dense understory can still thrive. The mixed wood understory, as it is called, supports the greatest diversity of forest wildlife in the aspen parkland.

Large shrubs such as red-osier dogwood, beaked willow, saskatoon, chokecherry and pincherry, along with the smaller shrubs including prickly rose, snowberry, beaked hazelnut and high bush cranberry, form a dense entangled understory. Dense shrubbery is a typical feature in aspen-dominated forests. Common herbs found in the woodlands include: Lindley's aster (Aster ciliolatus), northern bedstraw (Galium boreale), pea vine, Western Canada violet (Viola canadensis), dewberry and bunchberry. Mosses appear at the base of trees and on the ground.

Wetlands are very common in this biome, including lakes, shallow open water, marshes, and grassy wetlands. Glacial erosion has contributed to such features by creating depressions in which standing water can collect. In the larger depressions, permanent lakes or ponds of water remain. Many of the lakes have a saline character, thus most shore vegetation has a high tolerance of salty soils. These lakes are known as alkali lakes. Wet meadows are flooded in the spring and dry by fall. They contain rushes, sedges and grasses and provide excellent opportunities to study the similarities and differences of these forms of vegetation.

Rivers and streams erode valleys throughout the parkland ecoregion. Steep hills and ravines result in a unique topography. Southwest slopes with increased exposure to the sun are dry and often more grass covered, while the shaded north and east exposures retain more moisture and tend to have greater forest cover. Some forms of vegetation unique to the ravines include: poplar, spruce, birch, willow, and river alder.

Wildflowers are an important component of the grassland association of the parkland. Look for common yarrow, cut-leaf anemone, rock cress, creeping white prairie aster, milk vetch, late yellow loco weed, goldenrod, prairie rose, prairie crocus, and tiger lily.

The aspen understory

There are three main factors which influence the understory vegetation in the aspen stands of the mixed wood forest.

1. Good sun exposure encourages a dense vegetation growth below the canopy. This is of particular importance in the early spring before the trees are in leaf.

2. Warm soil and air temperature at the base level result in rapid melting process in spring which favours the growth of shrubs.

3. A large percentage of precipitation passes through the canopy. This provides a protective snow cover in winter and in warm seasons precipitation percolates through the leaf cover to nourish plants which require surface soil moisture.

The result of the above factors is an extensive understory of vegetation in the aspen forest. Common shrubs and herbs are: saskatoon, red-osier dogwood, raspberry, wild rose, currants and bracted honeysuckle, wild sarsaparilla, hairy lungwort, asters, and peavine. Twinflower, strawberries, bunchberries, horsetails and wintergreen form an attractive grown cover.

The mineral soil is covered by a decaying cover of organic matter. Numerous consumers and decomposers create humus materials. Burrowing animals mix the new fertile materials with the soil to form a rich rooting compound.

The spruce forest understory

Factors which influence the understory vegetation of spruce stands in the boreal forest association include:

1. Year round reduced sun exposure below the canopy restricts the forest undergrowth to shade tolerant species.

2. A large percentage of the precipitation is trapped in the upper tree boughs of the spruce forest and is released through evaporation. The ground cover of feather moss quickly absorbs most of the moisture which does penetrate the canopy. These factors combine to cause drier conditions in the underlying mineral soils.

3. The fallen acidic spruce needles are not fully decomposed and combine with the moss base. Water held in the moss carries the acid from the spruce needles into the mineral soil and leaches out soil nutrients – leaving a highly acidic, low nutrient soil base which is unsuitable for most boreal vegetation.

As a result of the above factors the forest floor ranges from nearly devoid of vegetation to a dense carpet of feather moss. A sparse community of shade tolerant shrubs exists in this environment. Some species of plants in the understory are Green Alder, low bush cranberry, prickly rose, bunchberry, twinflower, wild lily-of-the-valley, northern Comandra and wintergreens.

The mixedwood stands understory

There are several factors which influence the mixedwood stands in the boreal forest.

Where there are stands of aspen and spruce forests in close association with each other, a mixed wood forest occurs. Each group forms its own microassociation as described previously.

When the spruce and aspen forest types are mixed, the result can be quite different from the aspen or spruce stands. Animal and vegetation associations from each type combine to create considerable diversity of habitat which is typical of either spruce or aspen stands. The mixture of the transition soils provides an attractive environment with either pure spruce or pure aspen woodlands. An example of a bird which prefers a mixed wood habitat is the yellow-rumped warbler.

The mixedwood forest wetlands consist mainly of bogs, fens and marshes. Black spruce, tamarack, willow and bog and sphagnum mosses are the major vegetation types found in these lowlands. Dwarf birch and sedges cover large, wet areas with jack pine occurring on the sandy ridges.

For boreal aspen stands less than 40 years old, Comeau (2002)[10] found that basal area provided a useful general predictor of understorey light levels, but, on the basis of light measurements in one 80-year-old stand, cautioned that relationships between understorey light and basal area may not hold in older stands. The literature indicates that the height growth of understorey spruce should be maximized when light levels exceed 40% or when aspen basal area is < 14 m²/ha. Models developed by Wright et al. (1998)[11] show radial growth of understorey white spruce increasing almost linearly with increasing light and a continuous decline in radial increment with increasing aspen basal area. When applied to Comeau's (2002)[10] data, the Wright et al. (1998)[11] models suggest that spruce mortality will remain very low until aspen basal area exceeds 20 m²/ha, above which mortality will increase rapidly.

Fauna

Wildlife in the parklands include moose (Alces alces), white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), black bear (Ursus americanus), coyote (Canis latrans), northern pocket gophers (Thomomys talpoides), thirteen-lined ground squirrels, Richardson's ground squirrels, North American beaver (Castor canadensis), snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus), weasels and gray wolf (canis lupus). Bear, moose, foxes, coyotes, beaver, snowshoe hare and red squirrels are found most often in the mixedwood stands compared to the aspen forests and spruce forests.

Burrowing rodents such as Richardson's ground squirrels, thirteen-lined ground squirrels, and pocket gophers play a major role in the balance between the aspen groves and the grassland. These excavators make mounds of fresh soil which are ideal locations for the germination of poplar seeds. Once established, these trees spread by suckering, thus creating a new aspen groves.

White-tailed deer finds shelter in the aspen and graze on the grasslands; coyotes and foxes hunt the resident rodents. Historically, bison grazed on the grassland and helped to prevent the spread of aspen groves. However, bison are now mostly absent due to over hunting during settlement in the 19th century and extensive loss of habitat due to agriculture. Bison, however, can still be seen in protected areas such as Elk Island National Park east of Edmonton and in farms, where they are raised for meat.

Wildlife in the woodlands is varied and abundant. The varying hare, weasel, fox, coyote, and white-tailed deer make their homes in this region, while water dependent mammals who make the ravines and wetland areas of the ecoregion their home are beaver, muskrats, otters and mink.

Birds of the aspen parkland include kingfishers, ruffed grouse, magpies and northern orioles. and in particular several species of warblers find this a preferred habitat.

Extensive cultivation has disturbed the habitats of some birds which nest and feed on the fescue grassland. However, the horned lark and meadowlark have managed to adapt to the new conditions. Song sparrow, vesper sparrow, and American goldfinch can often be seen in open areas.

The woodlands meanwhile are abundant with a variety of bird species. Black-capped chickadee, hairy woodpeckers, ruffed grouse, magpies, and great horned owls can be observed in all seasons. Summer residents include: red-eyed vireo, least flycatcher and northern oriole.

Birds which prefer the wetland habitat include kingfishers and bank swallows. Finally there is an abundance of bird life around the wetland marshes. Many species of ducks make their summer homes in these waters and Canada geese nest in the more remote marshes. Blackbirds, marsh wrens and black terns nest in the reeds. Franklin gulls nest in the marsh vegetation, but range over agricultural fields for grasshoppers, crickets, and mice. Shore birds include: avocet, piping plover, spotted sandpiper, willet, common snipe and killdeer.

The invertebrate population in the woodland is enormous. Some of the most common invertebrates are roundworms, snails, segmented worms, centipedes, mites, spiders and mosquitoes. Poplar gore beetles and forest tent caterpillars are destructive to the tree cover. Insects of the wetlands in this region include caddis flies, mayflies and black flies.

Human use, threats and conservation

Before European colonization, there were large areas of western aspen and aspen parkland in the west of what would become Canada and the United States. This was maintained by light to moderate fires with a frequency of 3 to 15 years. Fire also swept the Rocky Mountains aspen as frequently as every ten years, creating large areas of parkland. Settlement increased fire frequency in the late 19th century until fire suppression became popular.[12]

Most of the aspen parkland, like the prairie biome, has been extensively altered by agriculture over the last 100 years since settlement first began in the late 19th century. While the climate is generally cooler than in the prairies, the climate is still mild and dry enough to support large-scale farming of crops such as canola (Brassica napsus), alfalfa (Medicago sativa) and wheat (Triticum aestivum), and livestock grazing. The soils in the aspen parkland biome are also quite fertile, especially around Edmonton and Saskatoon. Oil and natural gas exploration and drilling have also disturbed the natural habitat, especially in Alberta and northeastern British Columbia. As a result, less than 10% of the original habitat remains.

The largest blocks of intact parkland can be found in Moose Mountain Provincial Park north of Carlyle, Saskatchewan and Bronson Forest in Saskatchewan, and Elk Island National Park and Canadian Forces Base Wainwright in Alberta. The rest of the parkland area does contain fragments of original habitat, some in protected areas such as Spruce Woods Provincial Park and Turtle Mountain Provincial Park in Manitoba, and Porcupine Provincial Forest in Saskatchewan.

Human cultures

The First Nations of this region were not solely buffalo-hunting nomads, as were tribes to the south. They also relied to a great extent on trapping (rabbits, etc.) fishing, and deer and moose hunting, as well as gathering parkland berries, such as the Saskatoon berry or the high bush cranberry.

This area was one of the most important regions of the fur trade in North America. Both the Assiniboine and North Saskatchewan rivers were major fur trade routes, with a number of fur trade posts, much more so than rivers to the prairie south. The Métis people were formed around these posts from the intermarriage of white fur traders and native trappers.

Once European settlement began, this region was desired by the peasant farmers of Eastern Europe and the smallholders of Quebec for its wooded land, so that they could build and heat their own homes. This is as opposed to the primarily British and American settlers, who desired grasslands that were easier to break and plough. At the time, people of similar backgrounds were allowed to concentrate into block settlements by the federal government: for example the Edna-Star colony in Alberta, the largest concentration of Ukrainians on the prairies.

As a result of these different styles of indigenous hunting agricultural settlement, the ethnic makeup of the Prairie Provinces is somewhat divided north and south. Cree, Métis, French, and Ukrainian Canadians are concentrated in the parkland belt, and in parkland cities such as Edmonton, Saskatoon, and Winnipeg as opposed to prairie cities like Calgary and Regina, which were settled more so by people of Blackfoot, Sioux, American, English, and German backgrounds.

References

- Hoekstra, J. M.; Molnar, J. L.; Jennings, M.; Revenga, C.; Spalding, M. D.; Boucher, T. M.; Robertson, J. C.; Heibel, T. J.; Ellison, K. (2010). Molnar, J. L. (ed.). The Atlas of Global Conservation: Changes, Challenges, and Opportunits to Make a Difference. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26256-0.

- "Canadian Aspen forests and parklands". WWF. World Wildlife Foundation. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- http://dnr.state.mn.us/ecs/223/index.html

- Sarah Carter (1999). Aboriginal People and Colonizers of Western Canada to 1900. University of Toronto Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-8020-7995-4. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- http://ecozones.ca/english/zone/Prairies/ecoregions.html

- http://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/all/sag1497

- https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/na0802

- "Alberta's Parkland Region". raysweb.net. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- "Parks Canada - Waterton Lakes National Park - Green Scene - From Bottom To Top". Pc.gc.ca. 2013-01-23. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- Comeau, P. G. (2002). "Relationships between stand parameters and understory light in boreal aspen stands". B.C. Journal of Ecosystems and Management. 1 (2).

- Wright, E. F.; Coates, K. D.; Canham, C. D.; Bartemucci, P. (1998). "Species variability in growth response to light across climatic regions in northwestern British Columbia". Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 28 (6): 871–886. doi:10.1139/x98-055.

- Brown, James K.; Smith, Jane Kapler (2000). "Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on flora". Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 2. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. p. 40. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aspen parkland. |

- "Canadian Aspen forests and parklands". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Canadian Aspen forests and parklands (Vanderbilt University)