Battle of Zhovti Vody

Battle of Zhovti Vody (Ukrainian: Жовтi Води, Polish: Żółte Wody - literally "yellow waters": April 29 to May 16, 1648[5]) was the first significant battle of the Khmelnytsky Uprising. The name of the battle derived from a nearby Zhovta River.

| Battle of Zhovti Vody | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Khmelnytsky Uprising | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

4,000-5,000 Tatars 5000 Zaporizhian Cossacks[1] later 4,700 Registered Cossacks joined Khmelnytsky[2] |

3,000 men 6 cannons[3] later 1,000 men[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 150 dead[4] | entire contingent | ||||||

The events took place about 20 miles north of Zhovti Vody, today on the border of Kirovohrad Oblast and Dnipropetrovsk Oblast in south-central Ukraine when advance forces of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth army led by Stefan Potocki met a numerically superior force of Ukrainian Cossacks and Crimean Tatars under the command of Bohdan Khmelnytsky and Tuhaj Bej. After the Registered Cossacks who were originally allied with the Commonwealth arrived and unexpectedly sided with Khmelnytsky, the Commonwealth forces were annihilated while attempting to retreat following an 18-day battle, only days before reinforcements were to arrive.

Events leading to the battle

Preparation for the war with the Ottomans

With the death of Hetman Stanislaw Koniecpolski in March 1646, and without the knowledge of his successor Hetman Mikolaj Potocki, King Wladyslaw IV Vasa established direct relations with the Cossacks, concerning the "wrongs and injustices that they were suffering".[6]:365

In April 1646 after meeting with Cossack officers (starshyna), Władysław IV Vasa secretly chartered them for rallying to the Cossack army for the upcoming sea campaign against the Crimean Khanate,[7] increased the size of the Zaporozhian Host to 12,000 and gave them 6000 talers to equip "sixty well-armed boats".[6]:368–369 The king gave his letter to the Military Yesaul Ivan Barabash. who headed the Cossack Diplomatic Mission to the royal court.,[6]:369[7] Among other Cossack officers was Bohdan Khmelnytsky, who at that time was a company commander of Registered Cossacks Chyhyryn Regiment.[6]:369[7] Other members included another Yesaul, Ilyash Karaimovychm and regimental Yesaul Ivan Nestorenko.[6]:369[7]

Wladyslaw picked Lwow[7] as a rallying point for the campaign against the Tatars, stocking it with artillery, although that may have only been a rumor.[6]:358 These preparations led some to believe that the king was preparing for a government overtaking and the Kraków Senat of July 1646 requested that he stop all preparations, intending to raise that issue at the upcoming council session (Sejm).[7] Being left without support from the parliament, Wladyslaw was only hoping that the Cossacks,[7] nonetheless, were able to "obtain justice for themselves with their own forces".[6]:372

Barabash and Karaimovych, after hearing that the king had lost his support in the Sejm, refused to follow his orders and go against the decision of the Sejm, yet Bohdan Khmelnytsky decided to go forward with them.[7] He was able to gain control over the king's letter and decided to take Cossack recruiting onto himself. Barabash and Karaimovych informed about that the authorities and the Chyhyryn starosta Aleksander Koniecpolski set supervision over Khmelnytsky.[7] His assistant Daniel Czapliński, enraged by a complaint Khmelnytsky lodged against him, in 1646 made a raid on the Khmelnytsky estate village of Subotiv, killing his younger son[7] in the Chyhyryn market, seized Khmelnytsky's homestead, destroyed the manor and confiscated "grain and all kinds of property".[6]:382–383

At the beginning of May 1647 the next session of the Sejm took place, where it was planned to discuss the king's plans for war.[7] By the end of May Bohdan Khmelnytsky, with an escort of ten other Cossacks, appeared in Warsaw.[7] Officially his arrival could have been explained by his desire to seek justice in his case with Czapliński; however, in reality the goal of his appearance was much broader.[7] Since 1646 the Sejm had seen remarkable changes taking place, and Khmelnytsky wanted to reassure himself of the King's stance on the war with the Turks.[7] In case Wladyslaw still was planning to go forward, Khmelnytsky had intended to concentrate all the connections with the king and his supporters, as Barabash and Karaimovych sided with the opposition and refused material support to enable the king to realize his plans.[7] Khmelnytsky also wanted to find out whether the Sejm would change its position regarding the war plans.[7] In addition to all of that, Khmelnytsky and his comrades while visiting used that opportunity to study the situation in the region and gather all possible intelligence.[7] Although this and other accounts of Khmelneytsky's visit to Warsaw is doubted by Hrushevsky, since Khmelnytsky could not have turned to the king while he was "a property holder without title", but Khmelnytsky did become the target of political maneuvering, including "accusations of treason and incitement of the Cossacks to revolt."[6]:369

Khmelnytsky's conspiracy, arrest and bail

An important gathering took place in October 1647 near Chyhyryn,[8] where Khmelnytsky reminded the public about the situation in the region, the intentions of the King of Poland to start a war against the Ottomans and how the Polish magnates counteracted those plans. He showed the king's letter that had been given to him, and at the end announced that it was a good time for an uprising while there were disagreements between Poles. However, his audience was not too eager to follow those proclamations, pointing to their shortage of arms, the size of the Polish armed forces and other questions. Regarding their arguments Khmelnytsky said that it would be a good idea to ally with an outside force such as Russians or Tatars. However, Hrushevsky doubts Khmelnytsky had the king's letter, viewing this account as "popular legend".[6]:387

Sometime after the gathering Khmelnytsky was arrested in the village of Buzhyn, (30 kilometres (19 mi) north of Chyhyryn), by Radlinski, a servitor of Aleksander Koniecpolski, and was sent to Kryliv.[6]:384 Khmelnytsky was allowed to be released on the bond of Stanislaw Michal Krychewski, who cautioned Khmelnytsky[6]:384–385 about the plot to kill him.[9] "Having nowhere to turn for protection", Khmelnytsky "set out" for the Lower Dnieper River "to others who had been similarly mistreated".[6]:388 Khmelnytsky pretended that he was going with his escort (around 1,000 men, though some sources say 250[6]:388) to Trakhtemyriv (administrative center of Registered Cossacks), but suddenly turned and moved towards the Zaporizhian Sich together with his older son Tymish and 20 cavalrymen of his escort.

At that time one of his friends, Fedir Lyutai, a former Registered Cossack, was elected Kosh Otaman. Khmelnytsky arrived to Zaporizhia sometime on December 11, 1647[10] (by some other sources January 15, 1648),[11] where he was met by Lyutai on Tomakivka island. At that time on the neighboring island of Khortytsia were a Polish garrison of the Cherkasy Cossack Regiment and a unit of dragoons headed by Col. Górski. Upon the arrival of Khmelnytsky and his men the preparations for the uprising went faster. Several envoys were sent to the Don Cossacks and Bakhchysaray.[6]:390 However, in Crimea Tatars were skeptical of the uprising intended by the Cossacks, who were suppressed by "Ordination of 1638".

Attack on Khortytsia and the organization of expedition

At the end of January, Khmelnytsky led a surprise attack on the Khortytsia garrison. The bigger part of the registered Cossacks joined the mutineers, and Colonel Górski, after losing over 30 people, retreated to Kryliv. About that Adam Kisiel mentioned to the Putivl voivode, Prince Dolgoruki. "On 4 February N.S., the traitor Khmelnytsky attacked the Sich, where the Cherkasy regiment was standing guard, seized all the provisions, and took all the boats."[6]:389

After expelling the Polish garrison from the Zaporizhian Sich Khmelnytsky sent out several agitation letters to the public calling them to rise up against Poles ("summon them to unruliness").[6]:390 The letters were effective as more and more people were drawn to the Sich, accounting around 3,000[6]:390 to 5,000 by the end of February. During that time Cossacks continued to reinforce their fortifications on Butsk (Butska) Island.[6]:390

On March 15, 1648, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, together with his son Tymish and a small company, arrived at Bakhchisaray on a diplomatic mission. Khmelnytsky presented to Khan Giray the King's letter and proposed an alliance. After a few days of thinking Giray decided to send his mirza Tugay Bey[6]:391 into the expedition with Cossacks. After that Khmelnytsky returned to Sich, leaving his son with the Khan as "insurance". Upon arrival of Khmelnytsky, the Kosh otaman called for the General Council that was set for April 19. Because of the number of people attending the council it took place just outside the Sich itself. At the gathering the Cossacks unanimously expressed their will for the war against Poland and an immediate expedition. Bohdan Khmelnytsky was solemnly elected the Hetman. During the ceremony the Kosh otaman passed down to the new hetman the banner, the standard, and the military drums - the Cossack Kleinody (see Zaporizhian Cossacks).

It was decided that only eight thousand Cossacks would go out of the Sich while the rest would stay put as reserves. During the preparations to the Sich arrived the envoy of the Crown Hetman Mikołaj Potocki, rotmistrz Chmielecki,[6]:390 who offered Khmelnytsky and Cossacks the chance to leave Zaporizhia and disperse. To that Khmelnytsky said that it would happen if Potocki himself together with other Polish lords left Ukraine.[6]:390 Receiving such an answer Potocki in a great hurry moved with his army south.

The main element of Mikołaj Potocki was quartered in Cherkasy, while the Kalinowski's regiment stayed in Korsun, others in the estates of Crown Chorazy Aleksander Koniecpolski in Kaniv. The whole army of the Crown, designated to suppress the uprising, accounted for less than 7,000 soldiers.[6]:402 Before departing the Sich Khmelnytsky sent out Tugay-Bey with part of his unit (≈500 cavalry) on patrol having the task of securing a safe passage to the Sich for other volunteers. After receiving intelligence that the Polish Army is heading for the Kodak fortress,[6]:403 Khmelnytsky decided to leave the Sich on April 22 with his main element (≈2,000 Cossacks) towards Kryliv and Chyhyryn.

Before the battle

Around April 21–22, 1648, word of an uprising had spread through the Commonwealth. Either because they underestimated the size of the uprising,[12] or because they wanted to act quickly to prevent it from spreading,[13] the Commonwealth's Grand Crown Hetman Mikołaj Potocki and Field Crown Hetman Marcin Kalinowski sent a vanguard of 3,000 soldiers under the command of Potocki's son, Stefan (in fact, commanded by Commissioner Szemberg and Lieutenant Czarniecki)[6]:403 deep into Cossack territory, without waiting to gather additional forces from Prince Jeremi Wiśniowiecki. Stefan's force consisted of 7 banners of dragoons (700-800 men), 11 banners of cossack style cavalry (550 men) and 1 banner of Winged Hussars (150 men), the rest of his force was composed of about 1,500 registered Cossacks.[3][6]:403 While this group travelled by land, an additional detachment was sent down the Dnieper river in boats to join Stefan Potocki's forces in due course. These troops, under the command of Polkovnyk (colonel) Mykhailo Krychevsky, Stanislaw Wadowski, Stanislaw Gorski, Illiash Karaimovych and Ivan Barabash,[6]:403 were composed almost entirely of registered Cossacks (they also included about 80 of German dragoon) and numbered at around 3,500.[3]

A unit of 5,000 soldiers remained with Hetman Mikołaj Potocki while he attempted to gather local reinforcements from the various private armies of the local magnates, as well as from the pospolite ruszenie of the militant szlachta (Polish nobility).[5]

Stefan's force arrived first at the rendezvous point. It is likely that Krychevsky, en route, contacted Bohdan Khmelnytsky, his old friend (whom he helped to escape into Zaporizhian Sich a year earlier[5]) and the leader of the uprising.

The battle

On April 28, 1648, Stefan Potocki's forces came upon Khmelnytsky's army in an area near the present-day city of Zhovti Vody. Numbering only 3,000, the Commonwealth forces were greatly outnumbered at this point in comparison with Tatar-Cossack troops of 7,000-8,000, which consisted of 800 Cossacks, as well as 6,000-7,000 Crimean Tatars under the command of Tuhaj Bej.[14][3]

After the first small clashes between the Polish vanguard and Tatar scouts (27–29 April) Stefan Potocki arrived at Zhovti Vody and advised by Jacek Szemberk and Stefan Czarniecki[5] ordered his force to establish a camp in the tabor formation, which allowed for a messenger to be sent to contact Hetman Mikołaj Potocki, while they defended themselves over the next two weeks.[6]:403 The presence of the Tatars was a surprise to the Crown army, because they did not know about the Cossack-Tatar alliance. April 29, Tatars attacked Polish troops (three banners of cossack cavalry and 500-600 dragoons) that were before the tabor and after a short struggle forced the Poles to withdraw, the retreating Poles were duly supported by the next three cossack banners and possibly by other banners. The Tatars were defeated and suffered significant losses, decided not to continue the fight and withdrew. From the captured prisoners, the Poles heard that the Tatars were 12,000 strong, with more soon to come. In the hurriedly convened council of war, Polish commanders concluded that in the face of significant numerical superiority of the enemy (numbering according to the exaggerated statements prisoners allegedly 12,000 Tatars) it was impossible to fight a battle in the open field. There were two options, withdraw in tabor formation to Kryliv, or remain in place in the fortified camp in anticipation of the arrival of the main force hetmans. The Poles chose to remain. Under the leadership of Jan Fryderyk Sapieha, the Poles began to fortify a camp near the water.[15]

On April 30, the main Tatar force had arrived and four hours later the Cossack force joined them . Thereafter the Poles were encircled. On that day, there was no fighting. May 1, Tatars and Cossacks decided to launch an attack from two sides on the Polish camp, after the initial firing of the camp, the Cossacks began their attack. They tried to distract the defenders from Tugay Bey attacking them from behind, but the Tatars were late and attacked at a time when the Cossacks (after two unsuccessful attacks) had already withdrawn. This made it possible to effectively repulse the Tatars. Later Khmelnytsky and Tugay Bey still tried (4 or 5 times) to attack the Poles, but each time unsuccessfully. After a six-hour struggle, Tatars and Cossacks suffered significant losses and retreated. On the night of May 1 to May 2, the Cossacks built near the Poles a rampart and placed their cannons, but at dawn, the defenders quickly attacked, seized the position, and destroyed the fortifications. A period of blockade began, interrupted by frequent fighting (during the day attacked by Tatars, and at night by Cossacks).[16]

On May 4, 1648, near Kamianyi Zaton, Mykhailo Krychevsky's 3,500 registered Cossacks mutinied, killing all the officers (Krychevsky himself was taken prisoner and would join Khmelnytsky's army).[6]:404 Cossacks who stayed loyal to the Crown, such as Ivan Barabash, were cut down,[6]:404 as well as the German dragoons in their midst. Rebellious Cossacks arrived at the battlefield on May 13. The next day, Stefan Potocki saw his already undermanned force dwindle to 1,000 men, when the 1,200 registered Cossacks and some dragoons who arrived with Stefan also joined the uprising.[2][6]:405 Polkovnyk Ivan Hanzha is recognized as being instrumental in swaying his fellow registered Cossacks into taking Khmelnytsky's side. This created a gap in the Polish defense which the Cossacks attacked, supported by Tatars, but the attack was repulsed. At this point, Khmelnytsky's army swelled to more than 11,000. Despite the overwhelming numerical superiority, gaining Polish ramparts was not an easy task, especially in the absence of heavy artillery on the side of the Cossacks. Therefore, the Tatars and Cossacks decided to capture the Polish camp by guile. On the same day Tugay Bey proposed Poles negotiations.[2]

The hetmans, with an additional 4,000 strong army halted past Chyhyryn, built fortifications, but after news of the mutiny they retreated to the "settled area to their rear" and north of Chyhyryn on 13 May N.S.[6]:405

The Commonwealth army managed to hold off from being overrun; this was due in part to their superior artillery. On May 13, 1648, Khmelnytsky met with representatives of Stefan Potocki, who debated turning over their artillery in exchange for safe passage.[6]:405

Soon to Cossacks were sent deputies (e.g. Czarnecki, hostage-Cossack was Kryvonis). Khmelnitsky put up tough requirements: give to the Cossacks the Polish cannons, banners, and Commissioner Szemberg. The Poles agreed on everything except to give up Szemberg. Finally, an agreement was made. In return for the cannons, the Poles would receive safe passage. However, after giving up the cannons, Khmelnytsky broke the agreement, imprisoned the deputies imprisoned, and Colonel Kryvonis escaped. The next day there was an attempt to break out of the encirclement, Poles along with tabor began to walk towards the small fortified town Kryliv. They were, however, stopped at the cost of hundreds of soldiers captured by the Tatars. The Cossacks launched an assault but were repulsed. This was followed by another assault, the fighting continued until the evening and the Cossacks were repulsed again. Poles again decided to break through to Kryliv. May 16, after 1:00 a.m.[6]:405[17]

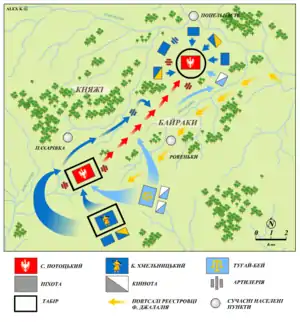

The Poles managed to get out of the encirclement, but the Tatars heard about the marching Poles and began to pursue. The Tatars attacked the Poles but were repulsed, Tugay Bey all night long trying to attack but without success. At dawn Polish wagons move on Kniazhi Bairaky, Cossacks are only now arrived at the place and began artillery fire on Poles, Tatars forced the Cossacks to stop firing because they wanted to taking as much as possible captives. Again Tatars and Cossacks rushed to the assault in which Stefan Potocki was wounded and Jan Sapieha took command but the attack was repulsed. A moment later began the second attack which was successful. The Commonwealth forces were surprised by a hail of arrows from Tuhaj Bej's Tatar forces,[6]:405 which diverted their escape route towards the nearby fortified village of Kniazhi Bairaky (today a tract in Piatykhatky Raion). There the combined forces of Tatar horsemen and Cossacks under the command of Khmelnytsky's Colonel Maksym Olshansky (aka "Crook-nose", Kryvonis, or Perebyinis) overwhelmed Potocki's tabor formation and thoroughly destroyed the fleeing force.[5][6]:405 300 towarzysz and soldiers were taken prisoner.[18] From the battlefield fled only one soldier but other source says that survived more soldiers.[19]

Hetman Mikołaj Potocki, who had received word on May 3, 1648, of his son's plight, could not move his forces in time to reinforce the Commonwealth's position, with his forces getting to within 100 km from the site of the battle.[5]

Aftermath

The majority of the Commonwealth forces either died in battle or were killed shortly thereafter. Stefan Potocki was wounded, taken prisoner of war and died[6]:405 from gangrene on May 19, 1648. His advisor, Stefan Czarniecki, was also taken prisoner, although he managed to escape soon thereafter.

Bolstered by their victory, the Cossack and Tatar forces engaged with the troops of Hetman Mikołaj Potocki and defeated them at the Battle of Korsuń.

Legacy

Monuments

Distinguishing the 350th Anniversary of Khmelnytsky Uprising, a monument commemorating the victory of Cossack and Tatar forces was erected near the village of Zhovto-Oleksandrivka, Piatykhatky Raion (Dnipropetrovsk Region), depicting two coats of arms: Bohdan Khmelnytsky's and Giray's. The monument's authors are an architect Volodymyr Shulha and a sculptor Stepan Zhylyak.[20]

In popular culture

The battle was very inaccurately portrayed in the 1999 film With Fire and Sword by Polish film director Jerzy Hoffman. Although the film paid much attention to historical details, the attempt to summarize the weeks-long battle in a few minutes meant that the battle as shown in the movie – reduced to the failed hussars' charge – had little in common with what had really happened, especially as the hussar forces in reality proved to be the backbone of Polish resistance during this 18-day battle.[5]

References

- Stepankov VS Battle Zhovtovods'ka 1648 [electronic resource] // Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine T. 3: E-AND / Redkol .: VA resin (chairman) and others. NAS of Ukraine. Institute of History of Ukraine. - K .: Prospect "scientific opinion", 2005. - 672 p,

- Witold Biernacki, Żółte Wody-Korsuń 1648, Bellona, Warszawa 2004, p 114-115, ISBN 83-11-09824-7. May 13, 3,500 the mutinous Registered Cossacks joined to Tatar-Cossack troops. May 14, 1,200 Registered Cossacks and some dragoons from Stefan Potocki troops changed sides and joined to Khmelnytsky

- Witold Biernacki, Żółte Wody-Korsuń 1648, Bellona, Warszawa 2004, p 86-90, ISBN 83-11-09824-7

- Doroshenko, D. Outline of History of Ukraine. Vol.2

- (in Polish) Bitwa pod Żółtymi Wodami -sprostowanie do filmu Jerzego Hoffmana.Last accessed on 23 December 2006.

- Hrushevsky, M., 2002, History of Ukraine-Rus, Volume Eight, The Cossack Age, 1626-1650, Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, ISBN 1895571324

- (in Ukrainian) Khmelnytsky and Zaporizhian Cossackdom Volodymyr Holobutsky Zaporizhian Cossacks, Chapter 11

- Chrząszcz, page 252

- Doroshenko, page 13

- Chronicles of Velychko

- Moscow State Acts. Vol.3. Document 357.

- Chirovsky, Nicholas: "The Lithuanian-Rus' Commonwealth, the Polish Domination, and the Cossack-Hetman State", page 176. Philosophical Library, 1984.

- (in Ukrainian)Terletskyi, Omelian: "History of the Ukrainian Nation, Volume II: The Cossack Cause", page 75. 1924.

- Witold Biernacki, Żółte Wody-Korsuń 1648, Bellona, Warszawa 2004, p 90-95, ISBN 83-11-09824-7

- Witold Biernacki, Żółte Wody-Korsuń 1648, Bellona, Warszawa 2004, p 95-103, ISBN 83-11-09824-7

- Witold Biernacki, Żółte Wody-Korsuń 1648, Bellona, Warszawa 2004, p 103-106, ISBN 83-11-09824-7

- Witold Biernacki, Żółte Wody-Korsuń 1648, Bellona, Warszawa 2004, p 115-118, ISBN 83-11-09824-7

- Witold Biernacki, Żółte Wody-Korsuń 1648, Bellona, Warszawa 2004, p 119-122, ISBN 83-11-09824-7

- Witold Biernacki, Żółte Wody-Korsuń 1648, Bellona, Warszawa 2004, p 122-123, ISBN 83-11-09824-7

- (in Russian) Platonov, V. Symbol of victory onto the Zholvti Vody. "Mirror Weekly" #34. August 22, 1998. Archived January 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

- Holobutsky, V. Zaporizhian Cossackdom. "Vyshcha shkola". Kiev, 1994. ISBN 5-11-003970-4 (http://litopys.org.ua/holob/hol.htm)

- Chrząszcz, J. Pierwszy okres buntu Chmielnickiego w oswietleniu uczestnika wyprawy Zoltowodzkiej // Prace historyczne w 30-lecie dzialanosci prof. St. Zakrzewskiego. Lwów, 1894.

- Doroshenko, D. Outline of History of Ukraine. Vol.2. Warsaw, 1933.

- Kubala, L. Szkice historyczne. Vol.3.

- Chronicles of Samiilo Velychko. Vol.1.

External links

- (in Polish) Żółte Wody 1648.

- (in Ukrainian) Military strategy of Bohdan Khmelnytsky