Battle of Kliszów

The Battle of Kliszów (Klissow) (Klezow) took place on July 8 (Julian calendar) / July 9 (Swedish calendar) / July 19, 1702 (Gregorian calendar) near Kliszów, Poland–Lithuania, during the Great Northern War.[7] The numerically superior Polish-Saxon army of August II the Strong, operating from an advantageous defensive position, was defeated by a Swedish army half its size under the command of King Charles XII.[8]

| Battle of Kliszów | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Great Northern War | |||||||

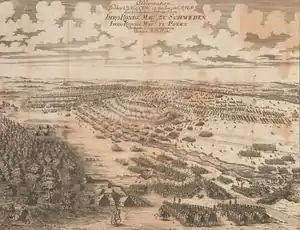

Contemporary drawing of the battle of Kliszów | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Charles XII Frederick IV of Gottorp † Rehnskiöld Vellingk Liewen |

Augustus II Steinau Schulenburg Flemming Lubomirski | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

12,000:[a] 4,000 horse, 4 three-pounder guns |

24,000:[b] 9,000 Saxon horse, 46 artillery pieces 660 Polish foot, 6,640 Polish horse, 4 or 5 cannon | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1,100:[c] 800 wounded |

4,400:[d] 900 wounded, 1,700 captured | ||||||

|

Notes

| |||||||

Prelude

August the Strong, Elector of Saxony, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, had in 1699 planned a three-fold attack on the Swedish Empire together with Peter the Great, Tsar of Russia and Frederik IV of Denmark-Norway.[9] The plan failed when Frederik was forced out of the war in 1700, after the Swedish landing on Humlebæk.[10] Charles XII of Sweden in the same year, defeated the Russian army in the battle of Narva.[11] After Narva, Charles XII evicted August the Strong's forces from Swedish Livonia through the battle of Düna and pursued him into the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[12] Charles occupied an undefended Warsaw on 14 May 1702 and marched west.[13]:688–689

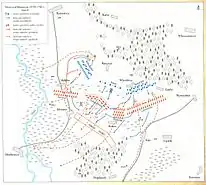

At Kliszów, south of Kielce, the Swedish and Saxon-Polish-Lithuanian armies encamped some 5 miles (8.0 km) apart. The camps were separated by a large wood and a swamp, with the Swedes north of the woods, Augustus the Strong's camp was naturally secured by a narrow stretch of swamp to the north and the swampy valley of the Nida river to the west. At 9:00 am, Charles XII moved his army through the woods on the morning of 19 July (NS) and at 11:00 am arrived north of the swampy stretch securing August's camp.[14] The army consisted of 8,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry and four guns — the bulk of the artillery was stuck in the forest. August's army consisted of 7,500 Saxon infantry, 9,000 Saxon cavalry, 660 Polish infantry, 6,640 Polish cavalry (including 1,240 hussars), and 46 guns.[3][14]

Battle

The Swedish right wing was under the command of Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld, the middle-first line under Hans Henrik von Liewen and the second under Knut Göransson Posse, the left wing had Frederick IV, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp first in command and Otto Vellingk second. The Saxon left wing and center was under the command of Adam Heinrich von Steinau respective Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg, the right (cavalry) wing was commanded by Jacob Heinrich von Flemming. The Polish cavalry was on the right wing and commanded by Hieronim Augustyn Lubomirski.[15]

Charles XII's strategy was to rout the Saxe-Polish forces in an 'envelope' maneuvre and re-position his forces to strengthen his flanks.[14] The Swedes took the initiative at two o'clock in the afternoon and launched an assault on Lubomirski's Polish flank, however, the commander of the assault, Frederick IV, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp was killed early on and the advance halted. The Polish army then launched two subsequent counter-attacks but were beaten back by the Swedish infantry, as were a Saxon assault over the marsh[14] under Jacob Heinrich von Flemming. Lubomirski and Flemming then withdrew and thus left the Saxon middle-right flank unprotected, which was caught in a Swedish pincer and were slowly crushed.[14] Lubomirski was pursued by Swedish cavalry all the way to the village of Kije.[6][14]

During this time, Swedish right flank under Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld was attacked by Saxon general Adam Heinrich von Steinau who tried to cut-off Rehnskiöld's connections with the Swedish bulk. A fierce fighting took place between '21 Swedish squadrons of cavalry with about 2,100 men', against '34 Saxon squadrons with no less than 4,250 men'. The Swedes, in their usual manner, attacked with cold steel and managed to repel the Saxon attack.[6]

Charles XII advanced into the Saxon camp by half past four and managed to evict them into the surrounding swamps.[14] He then took control over the Saxon artillery and used it for his own benefit.[6]

The Swedes now attempted to encircle the Saxons by taking the crossing of the Nida. General Schulenburg, whose infantry in the center had scarcely been attacked, now committed himself to a fierce defense of the crossing, allowing the majority of Saxon units to withdraw, and at five o'clock the battle was over.[6]

During the battle, Charles XII's brother-in-law Frederick IV, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp was killed by artillery fire - the firing of the shot is shown in Battle of Kliszów, an anonymous painting now in the Polish Army Museum. Up to 300 Swedes died with 800 wounded. About 2,000 Saxons and Poles were left on the field with another 1,700 taken prisoner of whom 1,100 were not wounded.[14][15]

Consequences

Charles had won the battle, but Schulenburg's actions had saved the Saxon army from destruction. The Swedes had captured the Saxon artillery, war chest and King August's entire baggage as well as 60 standards and banners. On July 31 Charles and his army marched into Kraków and consolidated control of Poland through 1703.[13]:689 August withdrew with his army to Sandomierz.[6]

The battle of Kliszów was also the last battle in which Winged Hussars took part, ending almost 130 years of battlefield dominance of this formation.

Sources

References

- Generalstaben (1918). Karl XII på slagfältet, II. P.A. Norstedt och söners förlag, Stockholm. pp. 413–414

- Carlson, Fredrik Ferdinand (1883). Sveriges historia under Konungarne af Pfalziska huset, II. Norstedt: Stockholm. p. 105

- Wagner, Marek. Kliszow 1702. Warsaw, 1994.

- Generalstaben (1918). Karl XII på slagfältet, I. P.A. Norstedt och söners förlag, Stockholm. pp. 438–439

- von Rosen, Carl (1936). Till kännedom om de händelser som närmast föregingo svenska stormaktsväldets fall, II. P.A. Norstedt & söner, Stockholm. p. 58

- Larsson (2009), p.140.

- Frost (2000), p.271

- Frost (2000), p.273

- Frost (2000), p.228

- Frost (2000) p.229

- Frost (2000), p.230

- Frost (2000), pp.229ff, 263ff

- Tucker, S.C., 2010, A Global Chronology of Conflict, Vol. Two, Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, LLC, ISBN 9781851096671

- Frost (2000), p.271-272

- Ericson (2003), p.268–273

Bibliography

- Frost, Robert I (2000). The Northern Wars. War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe 1558-1721. Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-06429-4.

- Ericson, Lars (2003). Svenska Slagfält. Wahlström & Widstrand. p. 268–273

- Larsson, Olle (2009). Stormaktens sista krig. Lund, Historiska Media. p. 140

- https://web.archive.org/web/20130716145912/http://www.wfgamers.org.uk/resources/C18/klezow.htm Orders of Battle