Battle of Front Royal

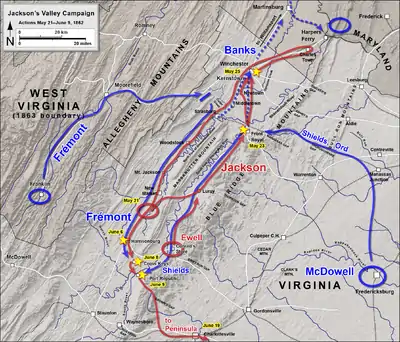

The Battle of Front Royal, also known as Guard Hill or Cedarville, was fought May 23, 1862, in Warren County, Virginia, as part of Confederate Army Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's Campaign through the Shenandoah Valley during the American Civil War. Front Royal demonstrated Jackson's use of Valley topography and mobility to unite his own forces while dividing those of his enemies. At a minimal cost, he forced the withdrawal of a large Union army by striking at its flank and threatening its rear. This caused President Abe Lincoln to react by sending General Irvin McDowell's forces that were intended for General George B. McClellan's advance on Richmond, and caused it to come to a halt. [3]

| Battle of Front Royal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

The Union Army under Banks entering the town, May 20, 1862. Forbes, Edwin, artist. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John Reese Kenly | Stonewall Jackson | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,063 [1] | 3,000 [1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

773 total 83 killed and wounded 691 captured [2] | 36 killed and wounded[2] | ||||||

Background

On May 21, 1862, the Union army under Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, numbering about 9,000 men, was concentrated in the vicinity of Strasburg, Virginia, with two companies of infantry at Buckton Depot. Col. John R. Kenly commanded 1,063 men and two guns at Front Royal. Confederate cavalry under Col. Turner Ashby confronted Banks near Strasburg, but then withdrew to join the main army, which crossed Massanutten Mountain via New Market Gap to reach Luray, Virginia. On May 22, Jackson's Army of the Valley (about 16,500 men) advanced along the muddy Luray Road to within ten miles of Front Royal. Jackson's headquarters were at Cedar Point. Colonel Thomas T. Munford's cavalry regiment was sent east to close off Manassas Gap and cut communication between Front Royal and Washington, D.C.[4]

Opposing forces

Union

Department of the Shenandoah[5]

Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks

- Forces at Front Royal

- Col. John R. Kenly

- 1st Maryland Infantry (9 cos.)

- 29th Pennsylvania Infantry (2 cos.)

- 1 co. of Pioneers

- 5th New York Cavalry (2 cos.)

Confederate

Department of the Valley[6]

Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson

- Ewell's Division

- Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell

- 1st Maryland Infantry: Col. Bradley T. Johnson

- Wheat's Battalion ("Louisiana Tigers"): Maj. C. Roberdeau Wheat

- 2nd Virginia Cavalry: Col. Thomas T. Munford

- 6th Virginia Cavalry: Col. Thomas Flournoy

- 7th Virginia Cavalry: Col. Turner Ashby

Battle

On the morning of May 23, the vanguard of Jackson's army reached Spangler's Crossroads (present day Limeton, Virginia). Here the Confederate cavalry under colonels Ashby and Thomas Flournoy diverged west to cross the South Fork of the Shenandoah River at McCoy's Ford. The infantry continued to Asbury Chapel and right onto a cross road to reach Gooney Manor Road. Following this road, they approached Front Royal from the south, bypassing Federal pickets stationed near the river on the Luray Road one mile south of the courthouse. After minor skirmishing the Federals withdrew.[4]

Jackson's leading brigade, under the leadership of Brig. Gen. Richard Taylor, deployed on Prospect Hill and along the ridge to the east. The 1st Maryland Infantry, CSA, and Major Roberdeau Wheat's Louisiana "Tigers" battalion were thrown out in advance, entering the town and clearing it of Union skirmishers. The battle is notable in that the 1st Maryland CSA was thrown into battle with their fellow Marylanders, the Union 1st Regiment Maryland Volunteer Infantry.,[7] the only time in United States military history that two regiments of the same numerical designation and from the same state have engaged each other in battle. On the day of the battle Captain William Goldsborough of the 1st Maryland Infantry, CSA, captured his brother Charles Goldsborough of the 1st Maryland Infantry, USA, and took him prisoner.[8]

Col. John Reese Kenly, in command of the Union forces, established his headquarters in the Vanoort House.[4] He withdrew his force to Camp (Richards') Hill, supported by a section of artillery. The Union line extended in an arc from the South Fork to Happy Creek, defending the South Fork bridge. Kenly's artillery opened fire and slowed the Confederate advance. The Confederate infantry advanced through town, deploying into line of battle under an accurate artillery fire. A Confederate flanking column moved to the east, crossing Happy Creek in an attempt to force Union withdrawal without a frontal assault. After a long delay because of the muddy roads, a battery of rifled artillery was deployed on or near Prospect Hill to counter the Union guns on Camp Hill.[4]

In the meantime, after crossing the South Fork at McCoy's Ford, Ashby's and Lt. Col. Flournoy's 6th Virginia Cavalry rode via Bell's Mill and Waterlick Station to reach the Union outpost at Buckton Depot. Ashby made a mounted assault, which cost him several of his best officers before the Union defenders surrendered. Ashby cut the telegraph lines, severing communication between the main Union army at Strasburg and the detached force at Front Royal. He then divided the cavalry, sending Flournoy's regiment east toward Riverton to threaten Kenly's rear. Ashby remained at Buckton Depot astride the railroad to prevent reinforcements from being sent to Front Royal.[4]

On discovering that Confederate cavalry was approaching from the west, Col. Kenly abandoned his position on Camp Hill, retreated across the South and North Fork bridges, and attempted to burn them. Sgt. William Taylor received the Medal of Honor for his gallantry in this action. Kenly positioned part of his command at Guard Hill, while the Confederates ran forward to douse the flames, saving the bridges. While Confederate infantry repaired the bridges for a crossing, Flournoy's cavalry arrived at Riverton and forded the river, pressing Kenly's forces closely. As soon as the Confederate infantry crossed, the Union position could be flanked by a column moving along the river. Kenly chose to continue his withdrawal, his outmatched cavalry fighting a rear guard action against Flournoy's 6th Virginia Cavalry.[4]

Kenly withdrew along the Winchester turnpike beyond Cedarville, Virginia, with Flournoy's cavalry in close pursuit. Jackson rode ahead with the cavalry, as Confederate infantry began to cross the rivers. At the Thomas McKay House, one mile north of Cedarville, Kenly turned to make a stand, deploying on the heights on both sides of the pike. Flournoy's cavalry swept around the Union flanks, causing panic. Kenly fell wounded, and the Union defense collapsed. More than 700 Union soldiers threw down their weapons and surrendered.[4]

Aftermath

The results of the battle were lopsided. Union casualties were 773, of which 691 were captured. Confederate losses were 36 killed and wounded.[2] Jackson's victory over the small Union force at Front Royal forced the main Union Army at Strasburg under Banks into abrupt retreat. Jackson deceived Banks into believing that the Confederate army was in the main Valley near Harrisonburg; instead he had marched swiftly north to New Market and crossed Massanutten via New Market Gap to Luray. The advance to Front Royal placed Jackson in position to move directly on Winchester, Virginia, in the rear of the Union army. On May 24, Banks retreated down the Valley Pike to Winchester, harassed by Confederate cavalry and artillery at Middletown and Newtown (Stephens City), setting the stage for the First Battle of Winchester the following day.[4]

The confusion engendered by Jackson's appearance at Front Royal and the hasty Union retreat from Strasburg to Winchester contributed materially to the defeat of Banks's army at First Winchester on May 25. Jackson used his cavalry to good advantage at Front Royal, to sever Union communications east and west, and to strike the final blow at Cedarville.[4]

After the battle, the victorious First Maryland CSA took charge of prisoners from the beaten Union First Maryland regiment. Many men recognized among them former friends and family. According to W. W. Goldsborough, who chronicled the history of the Maryland Line in the Confederate Army:

nearly all recognized old friends and acquaintances, whom they greeted cordially, and divided with them the rations which had just changed hands.[9]

Notes

- CWSAC Report Update

- Cozzens, p. 307; Salmon, p. 41, estimates 900 Union casualties and fewer than 100 Confederate; Clark, p. 128, cites 904 Union casualties (750 captured) and 35 Confederate; Kennedy, p. 81, cites 904 Union, 56 Confederate.

- https://www.historynet.com/americas-civil-war-front-royal-was-the-key-to-the-shenandoah-valley.htm

- NPS report on battlefield condition

- Martin, p. 107

- Martin, pp. 104-105

- Maryland Civil War units at www.2ndmdinfantryus.org/csunits.html Retrieved May 10, 2010

- [Goldsborough, W.W., Introduction, The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army, Butternut Press, Maryland (1983)

- Goldsborough, J. J., p.58, The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army Retrieved May 13, 2010

Bibliography

Print

- Clark, Champ, and the Editors of Time-Life Books (1984). Decoying the Yankees: Jackson's Valley Campaign. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books. ISBN 0-8094-4724-X.

- Cozzens, Peter (2008). Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3200-4.

- Goldsborough, W.W. (1983). "Introduction". The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army. Maryland: Butternut Press.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Maryland: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- Martin, David G. (1994). Jackson's Valley Campaign: November 1861 – June 1862 (Revised ed.). Philadelphia: Combined Books. ISBN 0-938289-40-3.

- Salmon, John S. (2001). The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.

Web

- National Park Service battle description

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "NPS report on battlefield condition".

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "NPS report on battlefield condition".- CWSAC Report Update

External links

Media related to Battle of Front Royal at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Front Royal at Wikimedia Commons- Animated History of Jackson's Valley Campaign