Baseball scorekeeping

Baseball scorekeeping is the practice of recording the details of a baseball game as it unfolds. Professional baseball leagues hire official scorers to keep an official record of each game (from which a box score can be generated), but many fans keep score as well for their own enjoyment.[1] Scorekeeping is usually done on a printed scorecard and, while official scorers must adhere precisely to one of the few different scorekeeping notations, most fans exercise some amount of creativity and adopt their own symbols and styles.[2]

History

Sportswriter Henry Chadwick is generally credited as the inventor of baseball scorekeeping. His basic scorecard and notation have evolved significantly since their advent in the 1870s[3] but they remain the basis for most of what has followed.

Abbreviations and grammar

Some symbols and abbreviations are shared by nearly all scorekeeping systems. For example, the position of each player is indicated by a number:

- Pitcher (P)

- Catcher (C)

- First baseman (1B)

- Second baseman (2B)

- Third baseman (3B)

- Shortstop (SS)

- Left fielder (LF)

- Center fielder (CF)

- Right fielder (RF)

- Rover or short fielder (used primarily in softball)

The designated hitter (DH), if used, is marked using a zero (0).

Scorecards

Scorecards vary in appearance but almost all share some basic features, including areas for:

- Recording general game information (date and time, location, teams, etc.)

- Listing the batting lineup (with player positions and uniform numbers)

- Recording the play-by-play action (usually the majority of the scorecard)

- Tallying each player's total at-bats, hits, runs, etc. at the end of the game

- Listing the pitchers in the game, including their statistics, such as innings pitched, strikeouts, earned runs, and bases on balls

Usually two scorecards (one for each team) are used to score a game.

Traditional scorekeeping

There is no authoritative set of rules for scorekeeping. The traditional method has many variations in its symbols and syntax, but this is a typical example.

In the traditional method, each cell in the main area of the scoresheet represents the "lifetime" of an offensive player, from at-bat, to baserunner, to being put out, scoring a run, or being left on base.

Outs

When an out is recorded, the combination of defensive players executing that out is recorded. For example:

- If a batter hits a ball on the ground to the shortstop, who throws the ball to the first baseman to force the first out, it would be noted on the scoresheet as 6–3, with 6 for the shortstop and 3 for the first baseman.

- If the next batter hits a ball to the center fielder who catches it on the fly for the second out, it would be noted as F8, with F for flyout and 8 for the center fielder. (In some systems, the letter 'F' is reserved for foul outs. A fly out would therefore be scored simply as '8'.) Other systems append a lower-case "ƒ" for foul balls, as in F9ƒ

- If the following batter strikes out, it would be noted as K, with the K being the standard notation for a strikeout. If the batter did not swing at the third strike, a "backwards K" (K, see right) is traditionally used. Other forms include "Kc" for a called third strike with no swing, or "Ks" if the batter did swing. A slash should be drawn across the lower right corner to indicate the end of the inning.

- If a runner is put out while on base, the next basepath is filled-in halfway, then ended with a short stroke perpendicular to the basepath. A notation is then added to indicate how the runner was out, along with the defensive combination that resulted in the out:

- CS means the runner was caught trying to steal the base ahead. The notation for a runner caught trying to steal second is normally 2–4 or 2–6 for a catcher-to-second-base play.

- PO means the runner was picked off by the pitcher while he was off the base. This almost always occurs at first base, so the notation is usually 1–3.

- DP or TP means the runner was out as part of a double or triple play. Usually, the full notation is left on the batter's line (the last out of the play); 6–4–3, 4–6–3, and 5–4–3 are common double-play sequences.

- FC means the out was the result of a fielder's choice to get out the runner on base rather than force out the batter. This can also be indicative of an unsuccessful attempt at a double or triple play as such a move is often the first move to make such a play.

Reaching base

If a batter reaches first base, either due to a walk, a hit, or an error, the basepath from home to first base is drawn, and the method described in the lower-righthand corner. For example:

- If a batter gets a base hit, the basepath is drawn and 1B or – (for a single-base hit) is written below.

- If the batter hits a double, however, the basepaths from home to first and first to second are drawn, and 2B or = is written above. This change of position is done to indicate that the runner did not advance on another hit. If the batter hits a triple, the basepaths are drawn from home to first to second to third and 3B or ≡ is written in the upper lefthand corner for the same reason.

- If a batter gets a walk, the basepath is drawn and BB (for Base on Balls) or W (for Walk) is written below. IBB is written for an intentional base on balls. Other indicators may be used if the batter is awarded first base for other reasons (HBP for being hit by a pitch, CI for catcher's interference, etc.).

- If the batter reaches first base due to fielder's choice (ex. the shortstop decides to force out the runner heading to second instead), the basepath is drawn and FC is written along with the sequence of the defense's handling of the ball, e.g., 6–4.

- If the batter reaches base because the first baseman dropped the throw from the shortstop, the basepath is drawn and E3 (an error committed by the first baseman) is written below.

- If a batter gets a base hit then in the same play advances due to a fielding error by the second baseman (ex. he misses the throw from the outfield, allowing the ball to get away), these are written as two events. First, the path to first is drawn with a 1B noted as for a single, then the path to second is drawn with an E4 noted above. This correctly describes the scoring—a single plus an error.

Advancing

When a runner advances due to a following batter, it can be noted by the batting position or the uniform number of the batter that advanced the runner. This kind of information is not always included by amateur scorers, and there is a lot of variation in notation. For example:

- If a runner on first is advanced to third base due to action from the 4th batter, number 22, the paths from first to second to third are drawn in and either a 4 or 22 could be written in the upper left hand corner. Whether that action was a base hit or a sacrifice will be noted on the batter's annotation.

- If a runner steals second while the 7th batter, number 32, is up to bat, the path from first to second would be drawn and SB followed by either a 7 or 32 could be written in the upper right hand corner. Note that Defensive Indifference (no attempt to throw out the runner) is denoted differently from a Stolen Base.

- For a batter to be credited with advancing the runner, the base advance must be the result of the batter's action. If a runner advances beyond that due to an error (such as a bad catch) or a fielder's choice (such as a throw to tag out a runner ahead of him), the advance due to the batter's action and the advance due to the other action are noted separately.

- To advance a player home to score a run, a runner must touch all 4 bases and cross all four base paths, therefore the scorer draws a complete diamond and, usually, fills it in. However, some scorers only fill in the diamond on a home run; they might then place a small dot in the center of the diamond to indicate a run scored but not a home run. The player that bats the runner home (or the other event such as an error that allows the runner to reach home) is noted in the lower left hand corner.

Miscellaneous

- End of an inning – When the offensive team has made three outs, a slash is drawn diagonally across the lower right corner of the cell of the third out. After each half-inning, the total number of hits and runs can be noted at the bottom of the column. After the game, totals can be added up for each team and each batter.

- Extra innings – There are extra columns on a scoresheet that can be used if a game goes to extra innings, but if a game requires more columns, another scorecard will be needed for each team.

- Substitutions – When a substitution is made, a vertical line is drawn after the last at-bat for previous player, and the new player's name and number is written in the second line of the Player Information section. A notation of PH or PR should be made for pinch hit and pinch run situations.

- Batting around – After the ninth batter has batted, the record of the first batter should be noted in the same column. However, if more than nine batters bat in a single inning, the next column will be needed. Draw a diagonal line across the lower left hand corner, to indicate that the original column is being extended.

Example

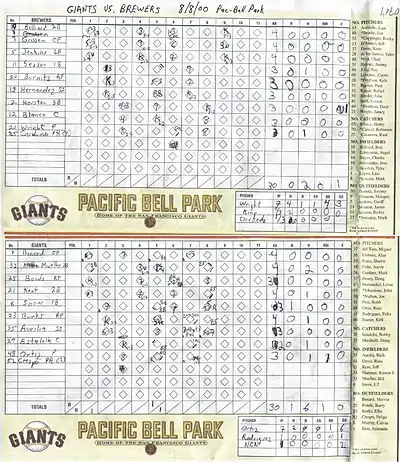

The scorecard on the right describes the August 8, 2000 game between the Milwaukee Brewers and San Francisco Giants, played at Pacific Bell Park, in San Francisco.[4] The scorecard describes the following events in the top of the 1st inning:

- 1st Batter, #10 Ronnie Belliard (the Brewers' 2nd baseman) grounded the ball to the Giants' 3rd baseman (5), who fielded the ball and threw it to 1st base (3) for the out. The play is recorded as "5-3."

- The notation ("3-2") in the lower right corner of the "Belliard:Inning 1 cell" indicates the pitch count at the time Belliard put the ball into play (3 balls and 2 strikes).

- 2nd batter, #9 Marquis Grissom (the Brewers' center fielder) grounded out 5-3 (3rd baseman to 1st baseman) on a 2-ball, 2-strike count.

- 3rd batter, #5 Geoff Jenkins (the Brewers' left fielder) grounded the ball to the 1st baseman (3) who took the ball to the base himself for an unassisted put out (3U).

One hard and fast rule of baseball scorekeeping is that every out and every time a baserunner advances must be recorded. The scoring can get a little more complicated when a batter who has reached base, is then "moved up" (advances one or more bases) by his own actions or by the actions of a hitter behind him. This is demonstrated in the Giants' first inning:

- 1st Batter, #7 Marvin Benard (the Giants' center fielder) hit a fly ball that was caught by the right fielder (9) for an out. Other scorekeepers might abbreviate this out using "F9" for fly out to right field.

- 2nd batter, #32 Bill Mueller (the Giants' 3rd baseman) hit a single: he hit the ball into play and made it safely to first base. This is denoted by the single line running from "home" to "1st" next to the diamond in that cell. Commonly, scorekeepers will place some abbreviation, such as "1B-7", to designate a single hit to left field. In addition, many scorekeepers also place a line across the diamond to show the actual path of the baseball on the field.

- 3rd batter, #25 Barry Bonds (the Giants' left fielder, incorrectly noted as a right fielder ("RF") on this scorecard) struck out (K) on a 1-ball, 2-strike count. At some point during Bonds' at-bat, Mueller, the runner on 1st base, stole 2nd base. This advancement was recorded in Mueller's cell by writing the notation "SB" next to the upper-right edge of the diamond.

- 4th batter, #21 Jeff Kent (the Giants' 2nd baseman) hit a fly ball that was caught by the Brewers' right fielder (9) for the third and final out of the inning. Mueller was stranded on 2nd base.

Stranded baserunners might be notated as being "LOB" (Left On Base) for that inning, with a number from 1-3 likely at the bottom of the inning column. For example, if two runners are left on base after the 3rd out, the scorekeeper might note "LOB:2", then at the end of the game calculate a total number of LOB for the game.

A more complicated example of scorekeeping is the record of the bottom of the 5th inning:

- 1st batter, #6 J. T. Snow (the Giants' 1st baseman and the fifth hitter in the Giants' lineup) advanced to first base on a walk (base-on-balls; BB).

- 2nd batter, #23 Ellis Burks (the Giants' right fielder) grounded out 5-3 (3rd baseman to 1st baseman). In the process, Snow advanced to second base.

- 3rd batter, #25 Rich Aurilia (the Giants' shortstop) flied out to the center fielder (8) for the second out of the inning.

- 4th batter, #29 Bobby Estalella (the Giants' catcher) drew a walk (BB) to advance to first base. Snow remained at 2nd base.

- 5th batter, #48 Russ Ortiz (the Giants' starting pitcher) hit a single (diagonal single line drawn next to the lower-right side of the diamond). Snow advanced to home plate on that single (the diagonal line drawn next to the lower left side of the diamond in Snow's "cell") to score the game's only run. Ortiz is given credit for an RBI (run batted in), denoted by the "R" written in the bottom left corner of his cell (incorrectly, since "R" indicates a 'run scored' and would more appropriately been noted in Snow's cell; "RBI" should have been written in Ortiz's cell). Estalella advanced from 1st to 3rd base on Ortiz's single (the diagonal line drawn next to the upper left side of the diamond in Estalella's "cell").

- 6th batter Marvin Bernard, up for the third time in this game, drew a walk (BB). Ortiz advanced to 2nd base on that walk (indicated by "BB" written on the "1st to 2nd" portion of the diamond in his cell.

- 7th batter Bill Mueller hit a ground ball to the 3rd baseman (5), who then threw the ball to the 2nd baseman (4) to force out Bernard at 2nd base (6-4) for the third and final out of the inning. As a force out also could have been performed by throwing the ball to 1st base, this is scored as a fielder's choice ("FC").

Project Scoresheet

Project Scoresheet was an organization run by volunteers in the 1980s for the purpose of collecting baseball game data and making it freely available to the public (the data collected by Major League Baseball was and still is not freely available). To collect and distribute the data, Project Scoresheet needed a method of keeping score that could be easily input to a computer. This limited the language to letters, numbers, and punctuation (no baseball diamonds or other symbols not found on a computer keyboard).

Scorecard

In addition to the new language introduced by Project Scoresheet, a few major changes were made to the traditional scorecard. First, innings of play are not recorded in a one-per-column fashion; instead all boxes are used sequentially and new innings are indicated with a heavy horizontal line. This saves considerable space on the card (since no boxes are left blank) and reduces the likelihood of a game requiring a second set of scorecards.

The second major change is the detailed offensive and defensive in/out system, which allows the scorekeeper to specify very specifically when players enter and leave the game. This is vital for attributing events to the proper players.

Lastly, each "event box" on a Project Scoresheet scorecard is broken down into three sections: before the play, during the play, and after the play. All events are put into one of these three slots. For example, a stolen base happens "before the play" because it occurs before the batter's at-bat is over. A hit is considered "during the play" because it ends the batter's plate appearance, and baserunner movement subsequent to the batter's activity is considered "after the play".

Language

The language developed by Project Scoresheet can be used to record trajectories and locations of batted balls and every defensive player who touched the ball, in addition to the basic information recorded by the traditional method. Here are some examples:

In the "before the play" slot:

- CS2(26): runner caught stealing 2B (catcher to shortstop)

- 1-2/SB: runner on 1B steals 2B

In "during the play" slot:

- 53: ground-out to third baseman ("5-3" in the traditional system)

- E5/TH1: error on the third baseman (on his throw to 1B)

In the "after the play" slot:

- 2-H: runner on 2B advances to home (scores)

- 1XH(92): runner on 1B thrown out going home (right fielder to catcher)

For a complete description of the language and the scorecard please see David Cortesi's documentation.

Reisner Scorekeeping

Project Scoresheet addressed a lack of precision in the traditional scorekeeping method, and introduced several new features to the scorecard. But while the Project Scoresheet language continues to be the baseball research community's standard for storing play-by-play game data in computers, the scorecards it yields are difficult to read due to the backtracking required to reconstruct a mid-inning play. Hence, despite its historical importance, the system has never gained favor with casual fans.

In 2002 Alex Reisner developed a new scorekeeping method that took the language of Project Scoresheet but redefined the way the event boxes on the scorecard worked, virtually eliminating the backtracking required by both Project Scoresheet and the traditional method. The system also makes it easy to reconstruct any mid-inning situation, a difficult task with the other two systems (for this reason it was originally promoted as "Situational Scorekeeping").

Scorecard

A Reisner scorecard looks like a cross between a traditional and Project Scoresheet scorecard. It has a diamond (representing the field, as in the traditional system) and a single line for recording action during and after the play (like Project Scoresheet's second and third lines). The diamond in each event box is used to show which bases are occupied by which players at the start of an at-bat. Stolen bases, pickoffs, and other "before the play" events are also marked on the diamond, so that one can see the "situation" in which an at-bat took place by simply glancing at the scorecard.

References

- "Keeping score". Archived from the original on 2005-07-01. Retrieved 2017-08-07.

- "Ways to get on base". Archived from the original on 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2017-08-07.

- Dickson, Paul. The Joy of Keeping Score. New York: Walker. ISBN 0-15-600516-6.

- "Milwaukee Brewers at San Francisco Giants, August 8, 2000". Baseball Reference. Retrieved 29 April 2013.