Auchenharvie Castle

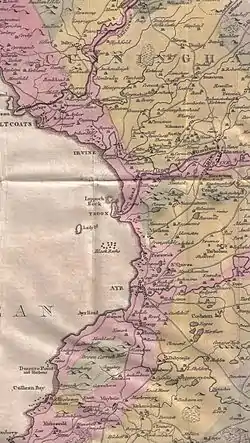

Auchenharvie Castle is a ruined castle near Torranyard on the A 736 Glasgow to Irvine road. Burnhouse lies to the north and Irvine to the south. It lies in North Ayrshire, Scotland.

| Auchenharvie Castle | |

|---|---|

| Torranyard, North Ayrshire, Scotland | |

Auchenharvie Castle in 2007 | |

Auchenharvie Castle | |

| Coordinates | 55.664972°N 4.604361°W |

| Grid reference | NS362442 |

| Type | Tower |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Alex Bicket Ltd |

| Controlled by | Cunningham Clan |

| Open to the public | Private. Hazardous. |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Built | 16th century |

| In use | Until 17th century |

| Materials | Whinstone |

History

The Castle

| Etymology |

| The meaning of Auchenharvie is suggested by Timothy Pont in 1604 - 08[2] as being 'the hill or 'knoppe' in the field of yellow corn'. |

The ruins still stand in a prominent and strongly defensible position at Auchenharvie Farm near Torranyard; the site has been much altered by quarrying. Previously the castle was known as Achin-Hervy, Awthinharye in c 1564 (Rollie 1980), Auchinbervy by Moll in 1745, Achenhay (1775 & 1807), and Auchenhowy is used by Ainslie in 1821.

Auchenharvie has long been a ruin, shown as such as far back as 1604 - 08 by Timothy Pont.[2] It was too small and the area of the mound also so restricted that its conversion into a more commodious and comfortable dwelling was not practicable.

The corbels of the parapet are unusual in that they project less than usual and this links Auchenharvie with the work at Law Castle and Barr Castle.[3] The castle is built from whinstone with freestone corners.[1]

A good deal remains of this typical tower castle, which has been ruinous since the 1770s, with indications of the barrel roof vaulting, side tower, ornate sandstone ornamentation, etc. Some very basic consolidation works have been carried out. Uncommon orchids have been recorded as growing on the motte.

It is known from the pollen record at Bloak Moss that extensive clearances took place here in the fifth or sixth centuries CE and such a site would have been of great strategic importance to these early settlers, standing out as it does, like an island above the mosses.[4] Castle Is Illegal to visit, also the castle is the smallest from The Three Towns (Saltcoats, Adrossan and Stevenson)

The Cunninghames of Auchenharvie

The castle had long been in the hands of the Cunninghames and notably. Edward Cunninghame of Auchenharvie was killed during a feud with the Clan Montgomery in 1526.[5] Auchenharvie's most famous owner was Dr. Robert Cunninghame who was created a Baronet of Nova Scotia in 1673 and was Physician to Charles II in Scotland, appointed shortly after the King's coronation at Scone in 1651. He was with the King's army at the defeat at Worcester in September 1651 and was made a prisoner in the Tower of London, being released after a ransom was paid. He was very wealthy and purchased back the Barony of Stevenston from the Earl of Eglinton in 1656. He died in 1676 and his son only outlived him by two years and because his daughter could not inherit, the land passed through the male line to her cousin, Robert Cunninghame.[6][7]

In January 1678 Robert Cunynghame, apothecary / druggist in Edinburgh, is stated to be the heir to Anne, daughter of Sir Robert Cunynghame of Auchenharvie. She was Robert's cousin-german and part of his inheritance was the Barony of Stevenston and the lands of Auchenharvie. He also owned some of the lands of Lambroughton and Chapeltoun. He married Anne Purves of Purves Hall in 1669 and had seventeen children. Despite his inheritance he later got into serious debt.[7]

The house belonged to Sir David Cunningham of Auchenharvie, an absentee courtier in England, till 1642. He planned to add additional building in 1634, beginning with a garden wall around the old tower. He had thought the house too small to accommodate his friends in 1628 during a planned royal visit, so he asked his cousin David Cunningham of Robertland to accommodate his mother so that if his friends visited they could stay at Robertland instead.[8]

In 1829 Aitken's map shows the castle as belonging to a Colonel Barns.[9]

The Resurrectionists

A local legend is that in the days of the 'body snatchers' or 'resurrectionists'; before the Anatomy Act of 1832, bodies obtained locally were hidden in the ruins before being taken up to Glasgow at night to sell to the surgeons and medical students at the old university who practiced dissection skills on them.[10] Another version of the story states that the bodies were collected together from neighbouring parishes at Darnshaw, a remote house near Bloak Moss on the old Auchenharvie to Megswell route. The bodies were then sold in Glasgow for £10 each to medicals students from the university.[11][12] The old toll road did run past the site and a toll gate and house stood fairly close by which must cast some doubt on the castle being involved.[10]

A local legend involves nearby Girgenti House and its prominent tower with smuggling.

Auchenharvie House

An estate named Auchenharvie was built by the family in Stevenston and although demolished, the name lives on in Auchenharvie Academy. Middleton near Annick Lodge had been part of the estate, passing into the hands of the Hamiltons of Bourtreehill and then passing to the Earls of Eglinton.[7] Robert Reid Cunninghame was one of the best known member of the family at its new site, being heavily involved in coal mining in the Barony of Stevenston.[13]

Lesley Baillie of 'Bonnie Lesley' fame was a descendant of the Cuninghames of Auchenharvie.[14]

The Toll Road

The old toll house close to Auchenharvie Castle farm was demolished in the 1990s and a private house with that name now stands on the site. The toll road junction is still extant as farm tracks. A road used to run across the fields from here to cut across the river by a ford below Megswell farm. This road passed beneath the Montgreenan driveway which was carried by a highly ornate bridge at this point. The construction of the Lochlibo Road made this route redundant.

Torranyard

| Etymology of Torranyard |

| The meaning of 'Tour' in Scots[15] is 'Tower', as in the prominent Auchenharvie castle tower nearby. A Yard in Scots[15] is a garden. 'Torranyard' could therefore be a corruption of 'Tour Inn yard.' Local people still pronounce the name 'Torranyard' as 'TOURanyard'. 'Torran' is also a Gaelic word meaning a small hill.[16] |

Torranyard is a hamlet at a crossroads on the Irvine to Glasgow 'Lochlibo Road'. It was recorded as 'Turing Yard' in 1747, 'Turnyard' in 1775, 'Tirranyard' on Thomson's 1820 map and in 1832. On the 1860 OS map it is shown as having a toll booth and an inn called 'Tour', on the opposite side of the road from the present Torranyard Inn (2007). The Montgreenan estate and hotel is nearby and the site of the old Girgenti house and surviving tower are nearby on the Cunninghamhead road.

Jamieson records that the inn at Burnhouse was nicknames the 'Trap 'Em Inn', the one at Lugton was called the 'Lug 'Em Inn', that at Auchentiber the 'Cleek 'Em Inn', and finally the one at Torranyard was called the 'Turn 'Em Out.'[17]

A William Forgisal (Fergushill) of Torranyard was miner at the Doura Pit in the 18th-century. He lost his leg in a mining accident, as had his father. William's wife was a tough sort, her comment being on seeing him so encumbered, was that the Forgisal's would need a small plantation of their own to keep them in crutches.[18]

The castle mound today is rich in wildflowers, however any visitor should beware as the castle sits in an elevated position with an unfenced vertical drop.

See also

References

- MacGibbon, T. and Ross, D. (1887-92). The castellated and domestic architecture of Scotland from the twelfth to the eighteenth centuries, 5v, Edinburgh. p 228.

- Pont, Timothy (1604). Cuninghamia. Pub. Blaeu in 1654.

- Campbell, Thorbjørn (2003). Ayrshire. A Historical Guide. Edinburgh : Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-267-0. p. 122

- Rackham, Oliver (1976) Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape. Pub. J.M.Dent & Sons Ltd. ISBN 0-460-04183-5. P. 52.

- Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Glasgow: John Tweed.

- Phillips, Alec, et al. The Auchenharvie Colliery an early history. The Three Towns History Group. Pub. Richard Stenlake. ISBN 1-872074-58-8. P. 4.

- Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604-1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Pub. John Tweed, Glasgow.

- National Records of Scotland: Cunningham Letters GD237/25/1-4: see NRS OPAC on-line catalogue

- Aitken, Robert (1829). The Parish Atlas of Ayrshire - Cunninghame. Edinburgh : W. Ballantine.

- Holder, Geoff (2010). Scottish Bodysnatchers. Port Stroud : The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5603-4. Page 54

- Strawhorn, John (1985). The History of Irvine. Pub. John Donald. ISBN 0-85976-140-1. P. 113.

- Love, Dane (1989). Scottish Kirkyards. London : Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7090-3667-1. p. 148

- Hughson, Irene (1996). The Auchenharvie Colliery - an early history. Ochiltree : Stenlake Publishing. ISBN 1-872074-58-8. pp. 5 - 12

- Wallace, Page 32

- A_Researcher's_Guide_to_Local_History_Terminology

- A History of Torrance House. Calderglen Country Park. South Lanarkshire Council. p. 3.

- Jamieson, Shiela (1997). Our Village. Greenhills WRI. Page 18

- Service, John (Editor) (1887). The Life & Recollections of Doctor Duguid of Kilwinning. Pub. Young J. Pentland. P. 140.

Bibliography

- Rollie, James (1980). The invasion of Ayrshire. A Background to the County Families. Pub. Famedram. P.83.

- Wallace, Archibald (1902). Stevenston. Past & Present. Stevenston : Archibald Wallace.

- Correspondence of David Cunningham of Auchinharvie to Robertland, National Archives of Scotland GD237/25/1-4