Ashcan comic

An ashcan comic is an American comic book originally created solely to establish trademarks on potential titles and not intended for sale. The practice was common in the 1930s and 1940s when the comic book industry was in its infancy, but was phased out after updates to US trademark law. The term was revived in the 1980s by Bob Burden, who applied it to prototypes of his self-published comic book. Since the 1990s, the term has been used to describe promotional materials produced in large print runs and made available for mass consumption. In the film and television industries, the term 'ashcan copy' has been adopted for low-grade material created to preserve a claim to licensed property rights.

Original use

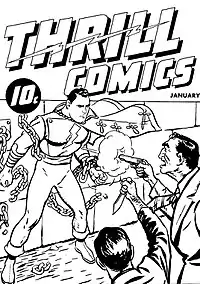

The modern comic book was created in the 1930s, and grew rapidly in popularity.[2] In the competition to secure trademarks on titles intended to sound thrilling, publishers including All-American Publications and Fawcett Comics developed the ashcan edition,[3] which was the same size as regular comics and usually had a black and white cover.[3] Typically, cover art was recycled from previous publications with a new title pasted to it.[4] Interior artwork ranged from previously published material in full color[3][4] to unfinished pencils without word balloons.[5] Some ashcans were only covers with no interior pages.[6] Production quality on these works range from being hand-stapled with untrimmed pages to machine-stapled and machine trimmed.[6] Once the practice was established, DC Comics used ashcans more frequently than any other publisher.[6] Not all the titles secured through ashcan editions were actually used for regular publications.[7]

The purpose of the ashcan editions was to fool the US Patent & Trademark Office into believing the book had actually been published.[8] Clerks at the office would accept the hastily produced material as legitimate, granting the submitting publisher a trademark to the title.[9][10] Since the ashcans had no other use, publishers printed as few as two copies; one was sent to the Trademark Office, the other was kept for their files.[11] Occasionally, publishers would send copies to distributors or wholesalers by registered mail to further establish publication dates,[4] but nearly all ashcan comic editions were limited to five copies or fewer.[3]

At the time, garbage cans were commonly called "ash cans" because they were used to hold soot and ash from wood and coal heating systems.[5] The term was applied to these editions of comics because they had no value and were meant to be thrown away after being accepted by the Trademark Office.[5][8] Some spare copies were given to editors, employees, and visitors to keep as souvenirs.[6][8] Changes to the United States trademark law in 1946 allowed publishers to register a trademark with an intent to use instead of a finished product,[6] and the practice of creating and submitting ashcans was abandoned when publishers began to consider it an unnecessary effort lawyers used to justify a fee.[7] Because of their rarity, ashcans from this era are desired by collectors and often fetch a high price.[5]

Later use

In 1984, Golden Age comic book collector and dealer Bob Burden created Flaming Carrot Comics, published by Aardvark-Vanaheim.[3][8][12] For each issue, Burden had magazine-sized prototype editions printed and shared them with friends and people who assisted with production.[3] Some were also sent to retailers as advance previews to generate interest in his comic.[8] Fewer than forty copies of each prototype were made, and Burden described them as ashcans.[3]

In 1992, comic creator Rob Liefeld applied the term to two digest-sized prototype versions of Youngblood #1, but this ashcan was created for mass release. Instead of denoting the material as worthless, Liefeld's usage implied rarity and collectability.[3] This ashcan was the first publication from Image Comics, a publisher started by popular artists during a boom period for comic books. The sales success of the Youngblood ashcans prompted imitation, and for the next year nearly every new Image series had a corresponding ashcan.[8] Typical print run for Image ashcans was between 500 and 5,000. Soon, other publishers began releasing ashcans in a variety of sizes and formats.[3] In 1993, Triumphant Comics advertised ashcan editions of new properties with print runs of 50,000.[13]

Following the collapse of the speculation market in comics in the mid-1990s, the term has been used by publishers to describe booklets promoting upcoming comics.[9] Established publishers such as Dark Horse Comics, IDW Publishing, and DC Comics continue to use ashcan copies as part of their marketing plan for new titles.[14][15][16] Aspiring creators also apply the term to hand-stapled photocopied books they use to demonstrate their abilities to hiring editors at comic book conventions or as part of a submissions package.[17]

Film and television

The term has been appropriated by the film and television industries to refer to low-quality material made specifically to preserve rights to a licensed character, which often expire if unused for a set period of time. One of the earliest examples of this practice is the 1967 animated adaptation of The Hobbit.[18] Other prominent examples include the 2011 Hellraiser: Revelations,[18] a 2015 adaptation of The Wheel of Time,[18] and the unreleased Fantastic Four film from 1994.[19]

See also

- Burning off, the airing of otherwise-abandoned television programs in less desirable time slots or on sister networks, often for contractual or legal reasons

References

- Hembeck, Fred (June 18, 2003). "Johnny Thunder and Shazam!". The Hembeck Files. Retrieved June 22, 2005.

- Ramsey, Taylor (February 5, 2013). "The History of Comics: Decade by decade". The Artifice. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- Christensen, William A; Seifert, Mark (February 1994). "Evolution of the Ashcan". Wizard. No. 30. New York City: Wizard Entertainment. p. 89.

- Seifert, Mark (August 1, 2014). "75 Years Ago Today: DC Comics Wins The Race For Flash". Bleeding Cool. Avatar Press. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- Malito, Alessandra (October 9, 2017). "As fans throng to New York Comic Con, these comic books sell for millions of dollars". MarketWatch. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- Colabuono, Gary (September 1999). "Absolutely Amazing DC Ashcans". Comic Book Marketplace. Vol. 2 no. 71. Coronado, CA: Gemstone Publishing, Inc. p. 24.

- Hamerlinck, Paul; Daigh, Ralph (2001). Fawcett Companion: The Best of FCA. Raleigh, NC: TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 107. ISBN 9781893905108.

- Colabuono, Gary (July 1993). "Ashcan Comics". Hero Illustrated. No. 1. Lombard, Illinois: Warrior Publications. p. 56.

- "Historic DC Ashcan Comic Books in Heritage New York Auction". CGC Comics. January 31, 2012. Archived from the original on June 26, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- "Historic DC Ashcan comic books in Heritage Auctions February 22 New York event". Art Daily. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- Cox, Brian L (August 13, 2011). "Rare 'ashcan' comic books on display at Chicago Comic Con". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- Mallette, Jack (November 1986). "Bob Burden (part 1)". Comics Interview. No. 40. Fictioneer Books. pp. 22–41.

- "Advertisement". Hero Illustrated. No. 2. Lombard, Illinois: Warrior Publications. August 1993. p. 125.

- Dietsch, TJ (April 12, 2012). "C2E2: Bobby Curnow Unleashes "Battle Beasts" at IDW". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Johnston, Rich (April 20, 2017). "Let's All Read The Dark Matter/Master Class Ashcan From DC Comics". Bleeding Cool. Avatar Press. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Johnston, Rich (March 12, 2015). "Dark Horse Sends Fight Club 2, Rebels And Archie Vs. Predator". Bleeding Cool. Avatar Press. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- Hart, Christopher (2014). Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy. Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony/Rodale. ISBN 9780770434861.

- Wirestone, Clay (March 13, 2015). "The Weird History of the "Ashcan Copy"". Mental Floss. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- Ito, Robert (March 2005). "Fantastic Faux!". Los Angeles. p. 108. Retrieved January 1, 2012.