Article 9 of the Constitution of Singapore

Article 9 of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore, specifically Article 9(1), guarantees the right to life and the right to personal liberty. The Court of Appeal has called the right to life the most basic of human rights, but has yet to fully define the term in the Constitution. Contrary to the broad position taken in jurisdictions such as Malaysia and the United States, the High Court of Singapore has said that personal liberty only refers to freedom from unlawful incarceration or detention.

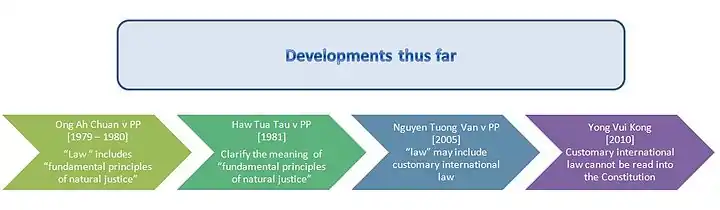

Article 9(1) states that persons may be deprived of life or personal liberty "in accordance with law". In Ong Ah Chuan v. Public Prosecutor (1980), an appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council from Singapore, it was held that the term law means more than just legislation validly enacted by Parliament, and includes fundamental rules of natural justice. Subsequently, in Yong Vui Kong v. Attorney-General (2011), the Court of Appeal held that such fundamental rules of natural justice embodied in the Constitution are the same in nature and function as common law rules of natural justice in administrative law, except that they operate at different levels of the legal order. A related decision, Yong Vui Kong v. Public Prosecutor (2010), apparently rejected the contention that Article 9(1) entitles courts to examine the substantive fairness of legislation, though it asserted a judicial discretion to reject bills of attainder and absurd or arbitrary legislation. In the same case, the Court of Appeal held that law in Article 9(1) does not include rules of customary international law.

Other subsections of Article 9 enshrine rights accorded to persons who have been arrested, namely, the right to apply to the High Court to challenge the legality of their detention, the right to be informed of the grounds of arrest, the right to counsel, and the right to be produced before a magistrate within 48 hours of arrest. These rights do not apply to enemy aliens or to persons arrested for contempt of Parliament. The Constitution also specifically exempts the Criminal Law (Temporary Provisions) Act (Cap. 67, 2000 Rev. Ed.), the Internal Security Act (Cap. 143, 1985 Rev. Ed.), and Part IV of the Misuse of Drugs Act (Cap. 185, 2008 Rev. Ed.) from having to comply with Article 9.

Text of Article 9

Article 9 of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore[1] guarantees to all persons the right to life and right to personal liberty. It states:

9.— (1) No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty save in accordance with law.

(2) Where a complaint is made to the High Court or any Judge thereof that a person is being unlawfully detained, the Court shall inquire into the complaint and, unless satisfied that the detention is lawful, shall order him to be produced before the Court and release him.

(3) Where a person is arrested, he shall be informed as soon as may be of the grounds of his arrest and shall be allowed to consult and be defended by a legal practitioner of his choice.

(4) Where a person is arrested and not released, he shall, without unreasonable delay, and in any case within 48 hours (excluding the time of any necessary journey), be produced before a Magistrate, in person or by way of video-conferencing link (or other similar technology) in accordance with law, and shall not be further detained in custody without the Magistrate's authority.

(5) Clauses (3) and (4) shall not apply to an enemy alien or to any person arrested for contempt of Parliament pursuant to a warrant issued under the hand of the Speaker.

(6) Nothing in this Article shall invalidate any law —

- (a) in force before the commencement of this Constitution which authorises the arrest and detention of any person in the interests of public safety, peace and good order; or

- (b) relating to the misuse of drugs or intoxicating substances which authorises the arrest and detention of any person for the purpose of treatment and rehabilitation,

by reason of such law being inconsistent with clauses (3) and (4), and, in particular, nothing in this Article shall affect the validity or operation of any such law before 10th March 1978.

Article 9(1) embodies the concept of the rule of law, an early expression of which was the 39th article of the Magna Carta of 1215: "No freeman shall be taken captive or imprisoned, or deprived of his lands, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed, nor will we go with force against him nor send forces against him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land."[2] Article 9(1) is similar, but by no means identical, to the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution which prohibits any state from denying "any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law", and to Article 21 of the Constitution of India which states: "No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law." Article 5(1) of the Constitution of Malaysia and Singapore's Article 9(1) are worded the same way as the latter was adopted in 1965 from the former following Singapore's independence from Malaysia.[3]

Rights to life and personal liberty

Meaning of life

.jpg.webp)

In Yong Vui Kong v. Public Prosecutor (2010),[4] the Court of Appeal of Singapore called the right to life "the most basic of human rights".[5] However, the courts have not yet had the opportunity to define the term life in Article 9(1).

Jurisdictions such as India, Malaysia and the United States interpret the same term in their respective constitutions broadly. In the United States Supreme Court case Munn v. Illinois (1877),[6] Justice Stephen Johnson Field stated that the term life means more than mere animal existence. Rather, the definition extends to all those limbs and faculties by which life is enjoyed. His rationale was that the term should not be "construed in any narrow or restricted sense".[7] Indian courts have likewise adopted a broad interpretation of life in Article 21 of the Indian Constitution to mean more than mere existence – instead, it includes the right to livelihood[8] and the right to a healthy environment. Subsequently, in Samatha v. State of Andhra Pradesh (1997),[9] the meaning of life was expanded to include the right to live with human dignity; and to the provision of minimum sustenance, shelter, and those other rights and aspects of life that make life meaningful and worth living. Similarly, Justice Prafullachandra Natwarlal Bhagwati held in Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India (1984)[10] that the expression life included the right to be free from exploitation, and to the basic essentials of life included in the Directive Principles of State Policy that appear in the Indian Constitution.[11]

In the Malaysian case Tan Tek Seng v. Suruhanjaya Perkhidmatan Pendidikan (1996),[12] the appellant had appealed against his wrongful dismissal from employment on the grounds of procedural unfairness. One of the issues brought up was whether an unfair procedure meant that he had been deprived of his constitutional right to life or liberty protected by Article 5(1) of the Malaysian Constitution, which is identical to Singapore's Article 9(1). Judge of the Court of Appeal Gopal Sri Ram held that the courts should take into consideration the unique characteristics and situation of the country, and must not be blind to the realities of life.[13] He went on to suggest that a liberal approach be adopted to grasp the intention of the framers of the Constitution by giving life a broad and liberal meaning. He opined that such an interpretation would include elements that form the quality of life, namely the right to seek and be engaged in lawful and gainful employment,[14] and the right to live in a reasonably healthy and pollution-free environment.[13] He also noted that life cannot be extinguished or taken away except according to procedure established by law.[15]

The Yong Vui Kong case suggests that Singapore courts may interpret the word life more narrowly than the Indian and Malaysian courts when called upon to do so. The Court of Appeal stated that the scope of Article 21 of the Indian Constitution had been expanded by the Indian courts to include "numerous rights relating to life, such as the right to education, the right to health and medical care and the right to freedom from noise pollution", attributing this to the "pro-active approach of the Indian Supreme Court in matters relating to the social and economic conditions of the people of India".[16] The Court declined to apply Mithu v. State of Punjab,[17] in which the mandatory death penalty had been found unconstitutional, stating it was "not possible" to interpret Singapore's Article 9(1) in the way that the Indian Supreme Court had interpreted Article 21 of the Indian Constitution.[5]

Meaning of personal liberty

Lo Pui Sang v. Mamata Kapildev Dave (2008)[18] took a narrow approach to the reading of personal liberty in Article 9(1). The High Court of Singapore held that personal liberty only refers to freedom from unlawful incarceration or detention, and does not include a liberty to contract. Although it was suggested this had always been the understanding of the term, no authority was cited.[19]

The approach taken in Lo Pui Sang can be compared to the more liberal interpretation of liberty in the United States and Malaysia. In the US Supreme Court case of Allgeyer v. Louisiana (1897),[20] where a Louisiana statute was struck down on the ground that it violated an individual's right to contract, it was held that liberty in the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution meant not only the right of the citizen to be free from any physical restraint of his person, but also the right to freely enjoy all his faculties – that is, to be free to use them in all lawful ways; to live and work where he will; to earn his livelihood by any lawful calling; to pursue any livelihood or avocation; and for that purpose to enter into all contracts that may be proper, necessary, and essential to his carrying out those purposes.[21] Liberty was accorded the same broad reading in the subsequent case Meyer v. Nebraska (1923),[22] in which the Supreme Court held that a state statute mandating that English be the only language used in schools was unconstitutional as it infringed on the liberty guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court stated that liberty

... denotes not merely freedom from bodily restraint but also the right of the individual to contract, to engage in any of the common occupations of life, to acquire useful knowledge, to marry, establish a home and bring up children, to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience, and generally to enjoy those privileges long recognized at common law as essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.[23]

It was held in the Malaysian Court of Appeal case of Sugumar Balakrishnan v. Pengarah Imigresen Negeri Sabah (1998)[24] that the term life in Article 5(1) of the Constitution is not limited to mere existence, but is a wide concept that must receive a broad and liberal interpretation. Likewise, personal liberty should be similarly interpreted, as any other approach to construction will necessarily produce an incongruous and absurd result.[25] On the facts, personal liberty extended to the liberty of an aggrieved person to go to court and seek judicial review, and thus a statutory provision that sought to oust the power of judicial review was apparently inconsistent with this fundamental liberty. However, the apparent inconsistency could be resolved by permitting an ouster clause to immunize from judicial review only those administrative acts and decisions that are not infected by an error of law.[26] Although the Federal Court reversed the Court of Appeal on this point,[27] in the subsequent case Lee Kwan Woh v. Public Prosecutor (2009)[28] the Federal Court held that the provisions of the Constitution should be interpreted "generously and liberally", and that "on no account should a literal construction be placed on its language, particularly upon those provisions that guarantee to individuals the protection of fundamental rights".[29] In its view:

... it is the duty of a court to adopt a prismatic approach when interpreting the fundamental rights guaranteed under Part II of the Constitution. When light passes through a prism it reveals its constituent colours. In the same way, the prismatic approach will reveal to the court the rights submerged in the concepts employed by the several provisions under Part II.[29]

The Federal Court went on to state that personal liberty "includes other rights" such as the right to "cross the frontiers in order to enter or leave the country when one so desires".[30]

It has been suggested that since Article 9(1) of the Singapore Constitution is pitched at a high level of generality,[31] there is no limitation in the ordinary natural meaning of the phrase. Thus, there is no requirement in the Constitution for personal liberty to be construed narrowly to mean only freedom from physical restraint.[32]

Meaning of save in accordance with law

The meaning of the word law in Article 9(1) has a direct bearing on the scope of the Article. If law is read broadly (for example, as incorporating customary international law principles), the scope of the fundamental liberties would be wider. It would be narrower if, on the other hand, law is construed narrowly, as the Legislature would be able to curtail such rights through legislation more easily. This could lead to a watering-down of the emphasis on fundamental liberties, as any infringement might be considered legitimate so long as the statute in question was validly enacted.

Fundamental rules of natural justice

In the Malaysian case Arumugam Pillai v. Government of Malaysia (1976),[33] the Federal Court construed the phrase save in accordance with law in Article 13(1) of the Constitution of Malaysia restrictively. This provision states: "No person shall be deprived of property save in accordance with law." The Court held that all that was required for the legislation in question to be constitutional was for it to have been validly passed by Parliament. Hence, the validity of any duly enacted piece of legislation could not be questioned on grounds of reasonableness, no matter how arbitrary the law appeared to be.[34]

However, in 1980 the Privy Council rejected this interpretation in the case of Ong Ah Chuan v. Public Prosecutor,[32] a decision on appeal from Singapore. This appeal questioned the constitutional validity of section 15 of the Misuse of Drugs Act,[35] and one of the issues that had to be decided was the interpretation of the word law in Article 9(1). The Public Prosecutor contended that law should be given a narrow meaning. He argued that

since 'written law' is defined in Art 2(1) to mean 'this Constitution and all Acts and Ordinances and subsidiary legislation for the time being in force in Singapore' and 'law' is defined as including 'written law', the requirements of the Constitution are satisfied if the deprivation of life and liberty has been carried out in accordance with provisions contained in any Act passed by the Parliament of Singapore, however arbitrary or contrary to fundamental rules of natural justice the provisions of such Act may be.[36]

However, the Public Prosecutor qualified the statement by providing a limitation, namely, that "the arbitrariness, the disregard of fundamental rules of natural justice for which the Act provides, must be of general application to all citizens of Singapore so as to avoid falling foul of the anti-discriminatory provisions of Art 12(1)".[36]

In a judgment delivered by Lord Diplock, the Privy Council rejected this interpretation, finding the Public Prosecutor's argument fallacious. Reading the definition of written law as stated in Article 2(1) together with Article 4, which provides that "any law enacted by the Legislature after the commencement of this Constitution which is inconsistent with this Constitution shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void", their Lordships held that "the use of the expression 'law' in Art 9(1) ... does not, in the event of challenge, relieve the court of its duty to determine whether the provisions of an Act of Parliament passed after 16 September 1963 and relied upon to justify depriving a person of his life or liberty are inconsistent with the Constitution and consequently void".[37]

In line with their view that Part IV of the Constitution should be given "a generous interpretation ... suitable to give to individuals the full measure of the [fundamental liberties] referred to",[38] their Lordships held that "references to 'law' in such contexts as 'in accordance with law', 'equality before the law', 'protection of the law' and the like ... refer to a system of law which incorporates those fundamental rules of natural justice that had formed part and parcel of the common law of England that was in operation in Singapore at the commencement of the Constitution".[39] This conception of the meaning of law in Article 9(1) has been affirmed by the Court of Appeal in Nguyen Tuong Van v. Public Prosecutor (2005)[40] and Yong Vui Kong v. Public Prosecutor (2010).[41]

It has been highlighted that this elevation of principles of natural justice to constitutional status, with the implication that they may override local statutes due to the supremacy of the Constitution over them, creates some tension with Article 38 which vests the law-making power of Singapore in the legislature.[42]

Extent of natural justice

In Ong Ah Chuan and the subsequent decision Haw Tua Tau v. Public Prosecutor (1981),[43] the Privy Council declined to set out a comprehensive list of fundamental rules of natural justice and merely stated some principles to deal with the issues at hand. At a 2000 conference, the Attorney-General Chan Sek Keong, who became Chief Justice in 2006, remarked that this gives the Court of Appeal a free hand to determine the scope of the fundamental rules of natural justice unencumbered by precedent.[44]

Guidance as to the scope of fundamental rules of natural justice was provided in Haw Tua Tau. First, the Privy Council said that rules of natural justice are not stagnant and may change with the times. Secondly, they should be considered in the local context, in light of the entire system as a whole and from the perspective of the people operating the system.[45] Further, in order to satisfy the rules of natural justice, the law in question should not be "obviously unfair".[46] In its view, under a system of justice in which the court is invested with partly inquisitorial functions, compelling an accused to answer questions put to him by a judge cannot be regarded as contrary to natural justice.[47] The Court of Appeal later ruled in Public Prosecutor v. Mazlan bin Maidun (1992)[48] that the privilege against self-incrimination was not a fundamental rule of natural justice, and thus not a constitutional right.

In Yong Vui Kong v. Attorney-General (2011),[49] the Court of Appeal stated that fundamental rules of natural justice embodied in the concept of law in constitutional provisions such as Articles 9(1) and 12(1) are the same in nature and function as common law rules of natural justice in administrative law, except that they operate at different levels of the legal order. The former invalidate legislation on the ground of unconstitutionality and can only be altered by amending the Constitution, while the latter invalidate administrative decisions on the ground of administrative law principles and can be abrogated or disapplied by ordinary legislation.[50]

A procedural or substantive concept?

Traditionally, at common law, natural justice is taken to be a procedural concept that embodies the twin pillars of audi alteram partem (hear the other party) and nemo iudex in causa sua (no one should be a judge in his or her own cause). In the United States, due process has both procedural and substantive components. Substantive due process involves the courts assessing the reasonableness of executive actions and legislation using rational basis review if a fundamental right is not implicated and strict scrutiny if it is. The question thus arises whether substantive fundamental rules of natural justice may be developed by local courts. However, a line of Malaysian cases has expressed the view that the concept of substantive due process is not applicable to Article 5(1) of the Malaysian Constitution, which is identical to Singapore's Article 9(1).[51] There is also academic commentary that rejects the notion of "substantive natural justice", arguing that it is too vague and leads to problems in application.[52] Another argument against substantive natural justice is the fear that it may become an avenue for judges to invalidate laws on the basis of their own subjective opinions, leading to unbounded judicial activism.

On the other hand, it has also been suggested that substantive natural justice would merely be a full exercise of the judiciary's proper role as conferred by the Constitution.[53] In addition, one scholar has asserted that there is no doubt that a judicial inquiry covers both substantive and procedural aspects. It is said that Article 9(1) connotes a judicial inquiry into the "fairness" of the law tested against certain principles regarded as fundamental to the legal system. Distinguishing between substantive and procedural fairness is a meaningless exercise, as it merely clouds the process of judicial inquiry. Judicial review is judicial review under whatever name, and as far as Article 9(1) is concerned, there is no room for making this distinction.[54]

However, in Yong Vui Kong v. Public Prosecutor (2010)[4] the Court of Appeal appeared to reject such an approach by declining to require that procedural laws must be "fair, just and reasonable"[55] before they can be regarded as law for the purpose of Article 9(1). It noted that the provision neither contains such a qualification, nor can such a qualification be implied from its context or wording. The Court considered it "too vague a test of constitutionality" and said: "Such a test hinges on the court’s view of the reasonableness of the law in question, and requires the court to intrude into the legislative sphere of Parliament as well as engage in policy making."[56] On the other hand, the Court acknowledged that Article 9(1) does not justify all legislation whatever its nature.[57] It held, obiter, that law might not encompass colourable legislation (that is, bills of attainder – legislation purporting to be of general application but in fact directed at securing the conviction of particular individuals), or legislation "of so absurd or arbitrary a nature that it could not possibly have been contemplated by our constitutional framers as being 'law' when they crafted the constitutional provisions protecting fundamental liberties".[58]

Customary international law

In Nguyen Tuong Van v. Public Prosecutor (2004), the Court of Appeal considered whether law in Article 9(1) includes principles of customary international law. In that case, the appellant argued that effecting a death sentence for drug trafficking by hanging is unconstitutional as a form of cruel and inhuman punishment not "in accordance with law". The Court agreed that there was a prohibition against torture and cruel and inhumane treatment in Article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and that this is considered customary international law. However, a customary international law rule had to be "clearly and firmly established" before it was adopted by the courts,[59] and there was insufficient practice among states to hold that death by hanging was within the ambit of this prohibition. Also, even if there was a customary international law rule against death by hanging, domestic statutes would prevail in the event of conflict.[60]

The Court of Appeal clarified in Yong Vui Kong v. Public Prosecutor (2010),[4] that customary international law cannot be read into the Constitution for two reasons. First, in order for a customary international law rule to have legal effect in Singapore, it has to be incorporated into domestic law. The incorporation can occur either by enactment in a statute[61] or by a court declaration that the rule forms part of the common law.[61] The Court felt it would be incorrect to incorporate customary international law rules into the meaning of law in Article 9(1) as this would cloak the common law with the constitutional status to nullify a statute, thus reversing the usual hierarchy of legal rules.[62] Secondly, the term law is defined in Article 2(1) to include the common law only "in so far as it is in operation in Singapore". However, a court cannot treat rules of customary international law as having been incorporated into Singapore common law if they are inconsistent with existing statutes. Furthermore, if there is a conflict between such a rule and a domestic statute, the latter prevails.[63]

The Constitution is silent as to the reception of international law in domestic law.[64] In Yong Vui Kong the Court of Appeal accepted that domestic law, including the Constitution, should "as far as possible" be consistently interpreted with Singapore's international obligations. Nonetheless, while international human rights law can increase the normative pool judges may resort to in interpreting the Constitution, there are "inherent limits" such as the express wording of the constitutional text and constitutional history that "[militates] against the incorporation of those international norms".[65]

It has also been argued that although where possible local statutes should be interpreted in light of international treaties, it is not the role of the judiciary to import international law standards into the Constitution that are inconsistent with legislation instead of deferring to the views of the executive. According to this view, which hinges on a strict adherence to the separation of powers doctrine, the judiciary should guard against unwarranted incursions into the executive sphere, as it is for the executive to determine Singapore's attitude and position in relation to foreign affairs. The judiciary must not undertake its task of interpreting the Constitution arbitrarily, but should accord with legal reasoning and sound principles.[66] This necessarily raises the question of what the applicable legal principle during the interpretation process should be. It has been suggested that the executive and the judiciary should show solidarity by speaking with "one voice",[67] and that the courts should exercise deference in favour of what the executive deems to be the nation's attitude towards the particular international law norm that is sought to be applied.[68]

It may be submitted that such judicial deference to the executive results in a clear neglect of the enshrined fundamental liberties in the Constitution. The flip side to this criticism is that fundamental liberties may still be given due accord though other avenues, for example, the application of rules of natural justice. As the meaning accorded to a particular fundamental liberty may be a potential ground for overturning Parliamentary legislation, it is crucial that the court should not merely rely on international law to determine the meaning of the liberty, unless there is evidence that the executive considers there is indeed an adoption of the particular international law norm.[69]

Application

Abortion

One of the most difficult questions involving the right to life is when exactly life begins and ends. If an unborn child is treated as a living person, then it should be accorded the right to life under the Constitution. Laws permitting abortion would thus be unconstitutional.[70] This issue has yet to come before the Singapore courts.

In Singapore, the Penal Code[71] lays out sanctions for non-compliance with the Termination of Pregnancy Act,[72] which limits abortion to women who have not been pregnant for more than 24 weeks.[73] By not conferring the right to life upon fetuses younger than the stipulated period, the legislation has accorded greater weight to the safety and security of expectant mothers who are threatened by their unborn children. This is in contrast with the approach taken in the Philippines, where the Constitution provides that the state shall equally protect the life of the mother and the life of the unborn from conception.[74] Similarly, the Charter of Fundamental Rights and Basic Freedoms of the Czech Republic states that human life deserves to be protected before birth.[75] Chances of a universal consensus on this issue are slim due to the difficulty in defining the beginning of life.

Right to die

In Singapore, attempted suicide,[76] abetment of suicide, and abetment of attempted suicide[77] are criminal acts. This applies to physicians who aid patients in ending their lives. Such physicians are unable to claim a defence under section 88 of the Penal Code since they intended to cause the patients' deaths.[78] However, physicians are absolved of liability if patients refuse treatment for terminal illnesses by issuing advance medical directives.[79]

Whether the right to life guaranteed by Article 9(1) encompasses a right to die – that is, a right to commit suicide or a right to assisted suicide, usually in the face of a terminal illness – has not been the subject of any Singapore court case. In other jurisdictions, the right to life has generally not been interpreted in this way. In Gian Kaur v. State of Punjab (1996)[80] the Indian Supreme Court held that the right to life is a natural right embodied in Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, and since suicide is an unnatural termination or extinction of life it is incompatible and inconsistent with the concept of the right to life.[81] The US Supreme Court has also declined to recognize that choosing death is a right protected by the Constitution. In Washington v. Glucksberg (1997),[82] a group of Washington residents asserted that a state law banning assisted suicide[83] was unconstitutional on its face. The majority held that as assisted suicide is not a fundamental liberty interest, it was not protected under the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Several of the justices seemed persuaded that the availability of palliative care to "alleviate suffering, even to the point of causing unconsciousness and hastening death"[84] outweighed recognizing a new unenumerated "right to commit suicide which itself includes a right to assistance in doing so".[85]

Rights of arrested persons

Article 9(2) of the Constitution enshrines the right of persons who have been detained to apply to the High Court challenging the legality of their detention. The application is for an order for review of detention, which was formerly called a writ of habeas corpus.[86] The Court is required to inquire into the complaint, and order the detainee to be produced before the Court and released unless it is satisfied that the detention is lawful.[87]

Article 9(3) requires that an arrested person be informed "as soon as may be" of the grounds of his arrest. Article 9(4) goes on to provide that if the arrested person is not released he must, without unreasonable delay, and in any case within 48 hours (excluding the time of any necessary journey) be produced before a magistrate and cannot be further detained in custody without the authority of the magistrate. The person's attendance before the magistrate may be in person or by way of video-conferencing or other similar technology in accordance with law.

Right to counsel

Article 9(3) also states that an arrested person must be allowed to consult and be defended by a legal practitioner of his choice.

Restrictions on the rights to life and personal liberty

As mentioned above, Parliament is entitled to restrict the rights to life and personal liberty as long as it acts "in accordance with law". More specific restrictions on Article 9 include Article 9(5), which provides that Articles 9(3) and (4) of the Constitution do not apply to enemy aliens or to persons arrested for contempt of Parliament pursuant to a warrant issued by the Speaker.

Detention under the Criminal Law (Temporary Provisions) Act and the Misuse of Drugs Act

Article 9(6) saves any law

- (a) in force before the commencement of the Constitution authorizing the arrest and detention of any person in the interests of public safety, peace and good order; or

- (b) relating to the misuse of drugs or intoxicating substances which authorizes the arrest and detention of any person for treatment and rehabilitation,

from being invalid because of inconsistency with Articles 9(3) and (4). This provision took effect on 10 March 1978 but was expressed to apply to laws in force prior to that date. Introduced by the Constitution (Amendment) Act 1978,[88] the provision immunizes the Criminal Law (Temporary Provisions) Act[89] and Part IV of the Misuse of Drugs Act[35] from unconstitutionality.

Preventive detention is the use of executive power to detain individuals on the basis that they are predicted to commit future crimes that will threaten national interest.[90] Among other things, the Criminal Law (Temporary Provisions) Act empowers the Minister for Home Affairs, if satisfied that a person has been associated with activities of a criminal nature, to order that he or she be detained for a period not exceeding 12 months if the Minister is of the view that the detention is necessary in the interests of public safety, peace and good order.[91]

Under the Misuse of Drugs Act, the Director of the Central Narcotics Bureau may order drug addicts to undergo drug treatment or rehabilitation at an approved institution for renewable six-month periods up to a maximum of three years.[92]

Detention under the Internal Security Act

Section 8(1) of Singapore's Internal Security Act ("ISA")[93] gives the Minister for Home Affairs the power to detain a person without trial for any period not exceeding two years on the precondition that the President is: "satisfied ... that ... it is necessary to do so ... with a view to preventing that person from acting in any manner prejudicial to the security of Singapore ... or to the maintenance of public order or essential services therein". The period of detention may be renewed by the President indefinitely for periods not exceeding two years at a time as long as the grounds for detention continue to exist.[94]

The ISA has its constitutional basis in Article 149 of the Constitution, which sanctions preventive detention and allows for laws passed by the legislature against subversion to override the Articles protecting the personal liberties of the individual.[95] Specifically, Article 149(1) declares such legislation to be valid notwithstanding any inconsistency with five of the fundamental liberty provisions in the Constitution, including Article 9.[96] Thus, detentions under the ISA cannot be challenged on the basis of deprivation of these rights.[97]

Notes

- Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (1999 Reprint).

- The version in force in the UK is Article 29 of the Magna Carta reissued by Edward I of England in 1297, which reads: "No Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will We not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the Land.": Magna Carta 1297 (1297 c. 9).

- Republic of Singapore Independence Act 1965 (No. 9 of 1965), s. 6(1).

- Yong Vui Kong v. Public Prosecutor [2010] 3 S.L.R. [Singapore Law Reports] 489, Court of Appeal (Singapore).

- Yong Vui Kong, p. 528, para. 84. This case is elaborated upon in the "Meaning of save in accordance with law" section below.

- Munn v. Illinois 94 U.S. 113 (1877), Supreme Court (United States).

- Munn, p. 142.

- Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corp. A.I.R. 1986 S.C. 180, Supreme Court (India); and Delhi Transport Corp. v. D.T.C. Mazdoor Congress A.I.R. 1991 S.C. 101, S.C. (India).

- Samatha v. State of Andhra Pradesh A.I.R. 1997 S.C. 3297, S.C. (India).

- Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India A.I.R. 1984 S.C. 802, S.C. (India).

- Bandhua Mukti Morcha, pp. 811–812.

- Tan Tek Seng v. Suruhanjaya Perkhidmatan Pendidikan [1996] 1 M.L.J. 261, Court of Appeal (Malaysia).

- Tan Tek Seng, p. 288.

- The court in Tan Tek Seng cited Chief Justice Yeshwant Vishnu Chandrachud in Olga Tellis who stated at p. 193: "An equally important facet of that right is the right to livelihood because, no person can live without the means of living, that is, the means of livelihood. If the right to livelihood is not treated as a part of the constitutional right to life, the easiest way of depriving a person of his right to life would be to deprive him of his means of livelihood to the point of abrogation." See Tan Tek Seng, p. 289.

- Tan Tek Seng, p. 289.

- Yong Vui Kong (2010), p. 528, para. 83.

- Mithu v. State of Punjab A.I.R. 1983 S.C. 473, S.C. (India).

- Lo Pui Sang v. Mamata Kapildev Dave [2008] 4 S.L.R.(R.) [Singapore Law Reports (Reissue)] 754, High Court (Singapore).

- Lo Pui Sang, p. 760, para. 6.

- Allgeyer v. Louisiana 165 U.S. 578 (1897), S.C. (United States).

- Allgeyer, p. 589.

- Meyer v. Nebraska 262 U.S. 390 (1923), S.C. (United States).

- Meyer, p. 399.

- Sugumar Balakrishnan v. Pengarah Imigresen Negeri Sabah [1998] 3 M.L.J. 289, C.A. (Malaysia).

- Sugumar, p. 305.

- Sugumar, p. 308.

- In Pihak Berkuasa Negeri Sabah v. Sugumar Balakrishnan [2002] 3 M.L.J. 72, Federal Court, Malaysia.

- Lee Kwan Woh v. Public Prosecutor [2009] 5 M.L.J. 301, F.C. (Malaysia).

- Lee Kwan Woh, p. 311, para. 8.

- Lee Kwan Woh, p. 314, para. 14, citing Government of Malaysia v. Loh Wai Kong [1978] 2 M.L.J. 175 at 178, H.C. (Malaysia).

- Jack Lee Tsen-Ta (1995), "Rediscovering the Constitution", Singapore Law Review, 16: 157–211 at 190.

- Lee, p. 191. Lee notes at p. 190 that in Ong Ah Chuan v. Public Prosecutor [1980] UKPC 32, [1981] A.C. 648, [1979–1980] S.L.R.(R.) 710, Privy Council (on appeal from Singapore), Lord Diplock indicated that the Constitution should not be treated as ordinary legislation but as "sui generis, calling for principles of interpretation of its own, suitable to its character": Ong Ah Chuan [1979–1980] S.L.R.(R.) at p. 721, para. 23, citing Minister of Home Affairs v. Fisher [1979] UKPC 21, [1980] A.C. 319 at 329, P.C. (on appeal from Bermuda).

- Arumugam Pillai v. Government of Malaysia [1975] 2 M.L.J. 29, F.C. (Malaysia).

- Arumugam Pillai, p. 30.

- Misuse of Drugs Act (Cap. 185, 2008 Rev. Ed.) ("MDA").

- Ong Ah Chuan, [1981] 1 A.C. at p. 670, [1979-1980] S.L.R.(R.) at p. 721, para. 24.

- Ong Ah Chuan, [1981] 1 A.C. at p. 670, [1979-1980] S.L.R.(R.) at p. 722, para. 25.

- Ong Ah Chuan, [1981] 1 A.C. at p. 670, [1979-1980] S.L.R.(R.) at p. 721, para. 23.

- Ong Ah Chuan, [1981] 1 A.C. at p. 670, [1979-1980] S.L.R.(R.) at p. 722, para. 26.

- Nguyen Tuong Van v. Public Prosecutor [2004] SGCA 47, [2005] 1 S.L.R.(R.) 103 at 125, para. 82, C.A. (Singapore), archived from the original on 15 November 2010.

- Yong Vui Kong (2010), pp. 499–500, para. 14.

- C.L. Lim (2005), "The Constitution and the Reception of Customary International Law: Nguyen Tuong Van v Public Prosecutor", Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, 1: 218–233 at 229, SSRN 952611.

- Haw Tua Tau v. Public Prosecutor [1981] UKPC 23, [1982] A.C. 136, [1981–1982] S.L.R.(R.) 133, P.C. (on appeal from Singapore).

- Chan Sek Keong (2000), "Rethinking the Criminal Justice System of Singapore for the 21st Century", in Singapore Academy of Law (ed.), The Singapore Conference: Leading the Law and Lawyers into the New Millennium @ 2020 (PDF), Singapore: Butterworths Asia, pp. 29–58 at 39–40, ISBN 978-981-236-106-6, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2011, retrieved 25 November 2010.

- Haw Tua Tau, [1982] A.C. at p. 154, [1981–1982] S.L.R.(R.) at p. 144, paras. 25–26.

- Haw Tua Tau, [1982] A.C. at p. 148, [1981–1982] S.L.R.(R.) at p. 137, para. 8.

- Haw Tua Tau, [1982] A.C. at p. 154, [1981–1982] S.L.R.(R.) at p. 144, para. 25.

- Public Prosecutor v. Mazlan bin Maidun [1992] 3 S.L.R.(R.) 968, C.A. (Singapore).

- Yong Vui Kong v. Attorney-General [2011] SGCA 9, [2011] 2 S.L.R. 1189, C.A. (Singapore).

- Yong Vui Kong (2011), pp. 1242–1243, paras. 104–105.

- See Public Prosecutor v. Datuk Harun bin Haji Idris [1976] 2 M.L.J. 116, High Court (Kuala Lumpur); Attorney-General, Malaysia v. Chiow Thiam Guan [1983] 1 M.L.J. 51, H.C. (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia); Public Prosecutor v. Lau Kee Hoo [1983] 1 M.L.J. 157, F.C. (Malaysia); Public Prosecutor v. Yee Kim Seng [1983] 1 M.L.J. 252, H.C. (Ipoh, Malaysia); and Che Ani bim Itam v. Public Prosecutor [1984] 1 M.L.J. 113, F.C. (Malaysia).

- A[ndrew] J. Harding (1981), "Natural Justice and the Constitution", Malaya Law Review, 23: 226–236.

- Jack Lee Tsen-Ta (1995), "Rediscovering the Constitution", Singapore Law Review, 16: 157–211 at 201.

- T.K.K. Iyer (1981), "Article 9(1) and 'Fundamental Principles of Natural Justice' in the Constitution of Singapore", Malaya Law Review, 23: 213–225 at 224–225.

- The approach taken to Article 21 of the Indian Constitution in Mithu, para. 6.

- Yong Vui Kong (2010), pp. 526–527, para. 80.

- Citing Ong Ah Chuan, [1980] A.C. at 659.

- Yong Vui Kong (2010), p. 500, para. 16; see also pp. 524–525, para. 75.

- Nguyen Tuong Van, pp. 126–127, para. 88.

- Nguyen Tuong Van, p. 128, para. 94.

- In which case the rule will be regarded as part of domestic legislation and no longer a customary international law rule: Yong Vui Kong (2010), p. 530, para. 89.

- Yong Vui Kong (2010), p. 530, para. 90.

- Yong Vui Kong (2010), p. 531, para. 91; Thio Li-ann (2010), "'It is a Little Known Legal Fact': Originalism, Customary Human Rights Law and Constitutional Interpretation: Yong Vui Kong v. Public Prosecutor", Singapore Journal of Legal Studies: 558–570 at 568–569, SSRN 1802666. The Court of Appeal also held that since a significant number of nations still retain the mandatory death penalty for drug-related offences and other serious crimes, it had not been established that customary international law prohibited the imposition of the mandatory death penalty: Yong Vui Kong (2010), p. 533, para. 96. Further, a customary international law rule prohibiting the mandatory death penalty cannot be regarded as part of law in Article 9(1) of the Constitution because the Government of Singapore rejected a recommendation to include a prohibition against inhuman punishment in the Constitution in 1966: p. 531, para. 92.

- Li-ann Thio (2004), "The Death Penalty as Cruel and Inhuman Punishment before the Singapore High Court?: Customary Human Rights Norms, Constitutional Formalism and the Supremacy of Domestic Law in Public Prosecutor v Nguyen Tuong Van (2004)", Oxford University Commonwealth Law Journal, 4 (2): 213–226 at 223, doi:10.1080/14729342.2004.11421445.

- Yong Vui Kong (2010), p. 519, para. 59; Thio, "Little Known Legal Fact", p. 569.

- Lim, "The Constitution and the Reception of Customary International Law", p. 230.

- C.L. Lim (2004), "Public International Law before the Singapore and Malaysian Courts" (PDF), Singapore Year Book of International Law, 8: 243–281 at 272, archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2012, retrieved 27 November 2010.

- Lim, "The Constitution and the Reception of Customary International Law", p. 233.

- Lim, "The Constitution and the Reception of Customary International Law", p. 231.

- For instance, see Dawn Tan (1997), "Christian Reflections on Universal Human Rights and Religious Values: Uneasy Bedfellows?", Singapore Law Review, 18: 216–250 at 220,

Since the advent of the modern human rights movement, the term 'human rights' has been bandied about with great fervour by its proponents; often, persons on opposite sides of an argument are able to defend their position by talking in terms of rights. For instance, abortion is condemned in the name of the foetus's right to life; the outlawing of abortion, in the name of the mother's right to choose – a women's right.

- Penal Code (Cap. 224, 2008 Rev. Ed.), ss. 313–316.

- Termination of Pregnancy Act (Cap. 324, 1985 Rev. Ed.) ("TPA").

- TPA, s. 4(a). Compare the Malaysian Penal Code (Act 574, 2006 Rev. Ed.), s. 312, which states that abortion is permissible within 120 days of conception only if the pregnancy poses a threat to an expectant mother's physical or mental health: see Ahmad Mesum (2008), "An Overview of the Right to Life under the Malaysian Federal Constitution", Malayan Law Journal, 6: xxxiv–xlix at xxxiv–xlviii.

- Constitution of the Philippines, Art. II, s. 12.

- Charter of Fundamental Rights and Basic Freedoms 1992 (Czech Republic), Art. 6.

- Penal Code, s. 309.

- Penal Code, s. 309 read with s. 107 (abetment); and s. 306 (abetment of suicide).

- Penal Code, s. 88, reads: "Nothing, which is not intended to cause death, is an offence by reason of any harm which it may cause, or be intended by the doer to cause, or be known by the doer to be likely to cause, to any person for whose benefit it is done in good faith, and who has given a consent." (Emphasis added.)

- Advance Medical Directive Act (Cap. 4A, 1997 Rev. Ed.), s. 20(1). Nothing in the Act authorizes an act that causes or accelerates death as distinct from an act that permits the dying process to take its natural course; or condones, authorizes or approves abetment of suicide or euthanasia: s. 17.

- Gian Kaur v. State of Punjab A.I.R. 1996 S.C. 1257, S.C. (India).

- Gian Kaur, para. 22.

- Washington v. Glucksberg 521 U.S. 702 (1997), S.C. (United States).

- Wash. Rev. Code Ann. §9A.36.060(1): "A person is guilty of promoting a suicide attempt when he knowingly causes or aids another person to attempt suicide."

- Glucksberg, p. 737.

- Glucksberg, p. 723.

- The application procedure is governed by Order 54 of the Rules of Court Archived 1 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine (Cap. 322, R 5, 2006 Rev. Ed.).

- Constitution, Art. 9(2).

- Constitution (Amendment) Act 1978 (No. 5 of 1978).

- Criminal Law (Temporary Provisions) Act (Cap. 67, 2000 Rev. Ed.) ("CLTPA").

- Claire Macken (2006), "Preventive Detention and the Right to Personal Liberty and Security under Article 5 ECHR", International Journal of Human Rights, 10 (3): 195–217 at 196, doi:10.1080/13642980600828487.

- CLTPA, s. 30.

- MDA, s. 34.

- Internal Security Act (Cap. 143, 1985 Rev. Ed.) ("ISA").

- ISA, s. 8(2).

- Yee Chee Wai; Ho Tze Wei Monica; Seng Kiat Boon Daniel (1989), "Judicial Review of Preventive Detention under the Internal Security Act – A Summary of Developments", Singapore Law Review, 10: 66–103 at 74.

- The other provisions are Arts. 11, 12, 13 and 14.

- Eunice Chua (2007), "Reactions to Indefinite Preventive Detention: An Analysis of how the Singapore, United Kingdom and American Judiciary give Voice to the Law in the Face of (Counter) Terrorism", Singapore Law Review, 25: 3–23 at 6.

References

Cases

- Ong Ah Chuan v. Public Prosecutor [1980] UKPC 32, [1981] A.C. 648, [1979–1980] S.L.R.(R.) [Singapore Law Reports (Reissue)] 710, Privy Council (on appeal from Singapore).

- Haw Tua Tau v. Public Prosecutor [1981] UKPC 23, [1982] A.C. 136, [1981–1982] S.L.R.(R.) 133, P.C. (on appeal from Singapore).

- Tan Tek Seng v. Suruhanjaya Perkhidmatan Pendidikan [1996] 1 M.L.J. [Malaya Law Journal] 261, Court of Appeal (Malaysia).

- Washington v. Glucksberg 521 U.S. 702 (1997), Supreme Court (United States).

- Sugumar Balakrishnan v. Pengarah Imigresen Negeri Sabah [1998] 3 M.L.J. 289, C.A. (Malaysia).

- Nguyen Tuong Van v. Public Prosecutor [2004] SGCA 47, [2005] 1 S.L.R.(R.) 103, Court of Appeal (Singapore), archived from the original on 15 November 2010.

- Lee Kwan Woh v. Public Prosecutor [2009] 5 M.L.J. 301, Federal Court (Malaysia).

- Yong Vui Kong v. Public Prosecutor [2010] 3 S.L.R. [Singapore Law Reports] 489, C.A. (Singapore).

Legislation

- Criminal Law (Temporary Provisions) Act (Cap. 67, 2000 Rev. Ed.) ("CLTPA").

- Internal Security Act (Cap. 143, 1985 Rev. Ed.) ("ISA").

- Misuse of Drugs Act (Cap. 185, 2008 Rev. Ed.) ("MDA").

- Penal Code (Cap. 224, 2008 Rev. Ed.).

Other works

- Lim, C.L. (2005), "The Constitution and the Reception of Customary International Law: Nguyen Tuong Van v Public Prosecutor", Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, 1: 218–233, SSRN 952611.

- Thio, Li-ann (2010), "'It is a Little Known Legal Fact': Originalism, Customary Human Rights Law and Constitutional Interpretation: Yong Vui Kong v. Public Prosecutor", Singapore Journal of Legal Studies: 558–570, SSRN 1802666.

Further reading

Articles

- Ganesh, Aravind (2010), "Insulating the Constitution: Yong Vui Kong v Public Prosecutor [2010] SGCA 20", Oxford University Commonwealth Law Journal, 10 (2): 273–292, doi:10.5235/147293410794895304, hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0029-6F3F-E.

- Lee, Jack Tsen-Ta (2011), "The Mandatory Death Penalty and a Sparsely Worded Constitution", Law Quarterly Review, 127: 192–195.

- McDermott, Yvonne (2010), "Yong Vui Kong v. Public Prosecutor and the Mandatory Death Penalty for Drug Offences in Singapore: A Dead End for Constitutional Challenge?", International Journal on Human Rights and Drug Policy, 1: 35–52, SSRN 1837822.

- Tey, Tsun Hang (2010), "Death Penalty Singapore-Style: Clinical and Carefree", Common Law World Review, 39 (4): 315–357, doi:10.1350/clwr.2010.39.4.0208.

- Thio, Li-ann (July 1997), "Trends in Constitutional Interpretation: Oppugning Ong, Awakening Arumugam?", Singapore Journal of Legal Studies: 240–290.

- Ramraj, Victor V[ridar] (2004), "Four Models of Due Process", International Journal of Constitutional Law, 2 (3): 492–524, doi:10.1093/icon/2.3.492.

Books

- Hor, Michael (2006), "Death, Drugs, Murder and the Constitution" (PDF), in Teo, Keang Sood (ed.), Developments in Singapore Law between 2001 and 2005, Singapore: Singapore Academy of Law, pp. 499–539, ISBN 978-981-05-7232-7, archived (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2011.

- Tan, Kevin Y[ew] L[ee] (2011), "Fundamental Liberties I: Protection of Life & Liberty", An Introduction to Singapore's Constitution (rev. ed.), Singapore: Talisman Publishing, pp. 146–165, ISBN 978-981-08-6456-9.

- Tan, Kevin Y[ew] L[ee]; Thio, Li-ann (2010), "Protection of Life & Liberty", Constitutional Law in Malaysia and Singapore (3rd ed.), Singapore: LexisNexis, pp. 735–794, ISBN 978-981-236-795-2.

- Tan, Kevin Y[ew] L[ee]; Thio, Li-ann (2010), "Rights of the Accused Person", Constitutional Law in Malaysia and Singapore (3rd ed.), Singapore: LexisNexis, pp. 795–838, ISBN 978-981-236-795-2.