Artemisia I of Caria

Artemisia I of Caria (Ancient Greek: Ἀρτεμισία; fl. 480 BC) was a queen of the ancient Greek city-state of Halicarnassus and of the nearby islands of Kos, Nisyros and Kalymnos,[2] within the Achaemenid satrapy of Caria, in about 480 BC.[2] She was of Carian-Greek ethnicity by her father Lygdamis I, and half-Cretan by her mother.[3] She fought as an ally of Xerxes I, King of Persia against the independent Greek city states during the second Persian invasion of Greece.[4] She personally commanded her contribution of five ships at the naval battle of Artemisium[5] and in the naval Battle of Salamis in 480 BC. She is mostly known through the writings of Herodotus, himself a native of Halicarnassus, who praises her courage and the respect in which Xerxes held her.[6][7]

| Artemisia | |

|---|---|

| Queen of Halicarnassus, Kos, Nisyros and Kalymnos | |

Artemisia, Queen of Halicarnassus, and commander of the Carian contingent, shooting arrows at the Greeks at the Battle of Salamis. Wilhelm von Kaulbach[1] | |

| Reign | 484–460 BC |

| Coronation | 484 BC |

| Predecessor | Her husband (name unknown) |

| Successor | Pisindelis |

| Born | 5th century BC Halicarnassus |

| Died | 5th century BC |

| Issue | Pisindelis |

| Greek | Ἀρτεμισία |

| Father | Lygdamis I |

| Mother | Unknown |

| Religion | Greek polytheism |

| Lygdamid dynasty (Dynasts of Caria) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||

Another Artemisia also is well-known, Artemisia II of Caria, satrap of Caria and builder of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus in the 4th century BC.

Family and name

Artemisia's father was the satrap of Halicarnassus, Lygdamis I (Λύγδαμις Α') [8][9][10] and her mother was from the island of Crete.[11][12] She took the throne after the death of her husband, as she had a son, named Pisindelis (Πισίνδηλις), who was still a youth.[13][14] Artemisia's grandson, Lygdamis II (Λύγδαμις Β'), was the satrap of Halicarnassus when Herodotus was exiled from there and the poet Panyasis (Πανύασις) was sentenced to death, after the unsuccessful uprising against him.

The name Artemisia derives from Artemis (n, f.; Roman equivalent: Diana), itself of unknown origin and etymology[15][16] although various ones have been proposed;[17][18] for example according to Jablonski,[18] the name is also Phrygian and could be "compared with the royal appellation Artemas of Xenophon; according to Charles Anthon the primitive root of the name is probably of Persian origin from arta*, art*, arte*,.. all meaning great, excellent, holy,.. thus Artemis "becomes identical with the great mother of Nature, even as she was worshipped at Ephesus";[18] Anton Goebel "suggests the root στρατ or ῥατ, "to shake," and makes Artemis mean the thrower of the dart or the shooter";[17] Plato, in Cratylus, had derived the name of the Goddess from the Greek word ἀρτεμής, artemḗs, i.e. "safe", "unharmed", "uninjured", "pure", "the stainless maiden";[17][18][19] Babiniotis while accepting that the etymology is unknown, states that the name is already attested in Mycenean Greek and is possibly of Pre-Greek origin.[16]

Battle of Salamis

Xerxes was induced by the message of Themistocles to attack the Greek fleet under unfavourable conditions, rather than sending a part of his ships to the Peloponnesus and awaiting the dissolution of the Greek armies. Artemisia was the only one of Xerxes' naval commanders to advise against the action, then went on to earn her king's praise for her leadership in action during his fleet's defeat by the Greeks at the Battle of Salamis (September, 480 BC).

Preparations

Before the battle of Salamis, Xerxes gathered all his naval commanders and sent Mardonios to ask whether or not he should fight a naval battle.[20] All the commanders advised him to fight a naval battle except Artemisia.[21]

As Herodotus tells it, she told Mardonios:

Tell the King to spare his ships and not do a naval battle because our enemies are much stronger than us in the sea, as men are to women. And why does he need to risk a naval battle? Athens for which he did undertake this expedition is his and the rest of Greece too. No man can stand against him and they who once resisted, were destroyed.[22]

If Xerxes chose not to rush into a naval encounter, but instead kept his ships close to the shore and either stayed there or moved them towards the Peloponnese, victory would be his. The Greeks can't hold out against him for very long. They will leave for their cities, because they don't have food in store on this island, as I have learned, and when our army will march against the Peloponnese they who have come from there will become worried and they will not stay here to fight to defend Athens.[23]

But if he hurries to engage I am afraid that the navy will be defeated and the land-forces will be weakened as well. In addition, he should also consider that he has certain untrustworthy allies, like the Egyptians, the Cyprians, the Kilikians and the Pamphylians, who are completely useless.[24]

Xerxes was pleased with her advice and while he already held her in great esteem he now praised her further. Despite this, he gave orders to follow the advice of the rest of his commanders. Xerxes thought that at the naval battle of Artemisium his men acted like cowards because he was not there to watch them. But this time he would watch the battle himself to ensure they would act bravely.[25]

Plutarch, in On the Malice of Herodotus, believe that Herodotus wrote that because he just wanted verses in order to make Artemisia look like a Sibyl, who was prophesying of things to come.[26]

Battle

Artemisia participated in the Battle of Salamis in September, 480 BC as a Persian ally. She led the forces of Halicarnassos, Cos, Nisyros and Calyndos (Κάλυνδος) (Calyndos was on the southwest coast of Asia Minor across Rhodes), and supplied five ships. The ships she brought had the second best reputation in the whole fleet, next to the ones from Sidon.[27]

Her involvement in the campaign was described by Herodotus:

Artemisia, who moves me to marvel greatly that a woman should have gone with the armament against Hellas; for her husband being dead, she herself had his sovereignty and a young son withal, and followed the host under no stress of necessity, but of mere high-hearted valour. Artemisia was her name; she was daughter to Lygdamis, on her father's side of Halicarnassian lineage, and a Cretan on her mother's. She was the leader of the men of Halicarnassus and Cos and Nisyrus and Calydnos, furnishing five ships. Her ships were reputed the best in the whole fleet after the ships of Sidon; and of all his allies she gave the king the best counsels. The cities, whereof I said she was the leader, are all of Dorian stock, as I can show, the Halicarnassians being of Troezen, and the rest of Epidaurus.

— Herodotus VII.99.[28]

As Herodotus says, during the battle, and while the Persian fleet was facing defeat, an Athenian ship pursued Artemisia's ship and she was not able to escape, because in front of her were friendly ships. She decided to charge against a friendly ship manned by people of Calyndos and on which the king of the Calyndians Damasithymos (Δαμασίθυμος) was located. The Calyndian ship sank.[29] Herodotus is uncertain but offers the possibility that Artemisia had previously had a disagreement with Damasithymos at the Hellespont.[30]

According to Polyaenus, when Artemisia saw that she was near to falling into the hands of the Greeks, she ordered the Persian colours to be taken down, and the master of the ship to bear down upon and attack a Persian vessel of the Calyndian allies, which was commanded by Damasithymus, that was passing by her.[31][32]

When the captain of the Athenian ship, Ameinias,[33] saw her charge against a Persian ship, he turned his ship away and went after others, supposing that the ship of Artemisia was either a Greek ship or was deserting from the Persians and fighting for the Greeks.[34][35]

Herodotus believed that Ameinias didn't know that Artemisia was on the ship, because otherwise he would not have ceased his pursuit until either he had captured her or had been captured himself, because "orders had been given to the Athenian captains, and moreover a prize was offered of ten thousand drachmas for the man who should take her alive; since they thought it intolerable that a woman should make an expedition against Athens."[36]

Polyaenus in his work Stratagems (Greek: Στρατηγήματα) says that Artemisia had in her ship two different standards. When she chased a Greek ship, she hoisted the Persian colours. But when she was chased by a Greek ship, she hoisted the Greek colours, so that the enemy might mistake her for a Greek and give up the pursuit.[37]

While Xerxes was overseeing the battle from his throne, which was at the foot of Mount Aigaleo, he observed the incident and he and the others who were present thought that Artemisia had attacked and sunk a Greek ship. One of the men who was next to Xerxes said to him: "Master, see Artemisia, how well she is fighting, and how she sank even now a ship of the enemy" and Xerxes then responded: "My men have become women; and my women, men." None of the crew of the Calyndian ship survived to be able to accuse her otherwise.[38] According to Polyaenus, when Xerxes saw her sink the ship, he said: "O Zeus, surely you have formed women out of man's materials, and men out of woman's."[39]

Photius writes that a man called Draco (Greek: ∆ράκων), who was the son of Eupompus (Greek: Εύπομπος) of Samos, was in the service of Xerxes for a thousand talents. He had a very good sight and could easily see at twenty stades. He described to Xerxes what he saw from the battle and how brave the Artemisia was.[40]

Aftermath

Plutarch, in his work Parallel Lives (Greek: Βίοι Παράλληλοι) at the part which mention Themistocles, says that it was Artemisia who recognised the body of Ariamenes (Ἀριαμένης) (Herodotus says that his name was Ariabignes), brother of Xerxes and admiral of the Persian navy, floating amongst the shipwrecks, and brought the body back to Xerxes.[41]

After the Battle of Salamis

After the battle, according to Polyaenus, Xerxes acknowledged her to have excelled above all the officers in the fleet and sent her a complete suit of Greek armour; he also presented the captain of her ship with a distaff and spindle.[45][46]

According to Herodotus, after the defeat, Xerxes presented Artemisia with two possible courses of action and asked her which she recommended. Either he would lead troops to the Peloponnese himself, or he would withdraw from Greece and leave his general Mardonius in charge. Artemisia suggested to him that he should retreat back to Asia Minor and she advocated the plan suggested by Mardonius, who requested 300,000 Persian soldiers with which he would defeat the Greeks in Xerxes' absence.[47]

According to Herodotus she replied: "I think that you should retire and leave Mardonius behind with those whom he desires to have. If he succeeds, the honour will be yours because your slaves performed it. If on the other hand, he fails, it would be no great matter as you would be safe and no danger threatens anything that concerns your house. And while you will be safe the Greeks will have to pass through many difficulties for their own existence. In addition, if Mardonius were to suffer a disaster who would care? He is just your slave and the Greeks will have but a poor triumph. As for yourself, you will be going home with the object for your campaign accomplished, for you have burnt Athens."[48]

Xerxes followed her advice, leaving Mardonius to conduct the war in Greece. He sent her to Ephesus to take care of his illegitimate sons.[49] On the other hand, Plutarch mocks Herodotus' writing, since he thinks that Xerxes would have brought women with him from Susa, in case his son needed female attendants.[26]

Opinions about Artemisia

Herodotus had a favourable opinion of Artemisia, despite her support of Persia and praises her decisiveness and intelligence and emphasises her influence on Xerxes.

Polyaenus says that Xerxes praised her gallantry. He also in the eighth book of his work Stratagems, mentions that when Artemisia (he may have referred to Artemisia I, but most probably he referred to Artemisia II) wanted to conquer Latmus, she placed soldiers in ambush near the city and she, with women, eunuchs and musicians, celebrated a sacrifice at the grove of the Mother of the Gods, which was about seven stades distant from the city. When the inhabitants of Latmus came out to see the magnificent procession, the soldiers entered the city and took possession of it.[50]

Justin in the History of the World mentioned that she "was fighting with the greatest gallantry among the foremost leaders; so that you might have seen womanish fear in a man, and manly boldness in a woman."[51]

On the other hand, Thessalus, a son of Hippocrates, described her in a speech as a cowardly pirate. In his speech, Thessalus said that the King of Persia demanded earth and water from the Coans in 493 BC but they refused, so he gave the island to Artemisia to be wasted. Artemisia led a fleet of ships to the island of Cos to slaughter the Coans, but the gods intervened. After Artemisia's ships were destroyed by lightning and she hallucinated visions of great heroes, she fled Cos.[52] However, she later conquered the island.[53]

Death and cultural depictions in the ancient world

A legend, quoted by Photius,[54] some 13 centuries later, claims that Artemisia fell in love with a man from Abydos (Ancient Greek: Ἄβῡδος), named Dardanus (Greek: Δάρδανος), and when he ignored her, she blinded him while he was sleeping, but her love for him increased. An oracle told her to jump from the top of the rock of Leucas, but she was killed after she jumped from the rock and buried near the spot. Those who leapt from this rock were said to be cured from the passion of love. According to a legend, Sappho killed herself jumping from these cliffs too, because she was in love with Phaon.

Aristophanes mentioned Artemisia in his works Lysistrata[55] and Thesmophoriazusae.[56]

Pausanias, in the third book of his work Description of Greece (Greek: Ἑλλάδος Περιήγησις), entitled Laconia (Greek: Λακωνικά) mentioned that in the marketplace of Sparta the most striking monument was the portico which they called Persian (Greek: στοὰ Περσικὴν), because it was made from spoils taken in the Persian wars. Over time, the Spartans altered it until it became very large and splendid. On the pillars were white-marble figures of Persians, including Mardonius. There was also a figure of Artemisia.[57][58][59]

Also, the encyclopedia called the Suda mentioned Artemisia.[60]

Artemisia was succeeded by her son Pisindelis, who became the new tyrant of Caria.[61] He would himself later be succeeded by his son Lygdamis.[61]

Modern cultural references

.jpg.webp)

Several modern ships were named after Artemisia. An Iranian destroyer (Persian: ناوشکن) purchased during the Pahlavi dynasty was named Artemis in her honour.[62] This destroyer was the largest ship in the Iranian Navy. The previous name of the Greek ferryboat, Panagia Skiadeni, was Artemisia (ex-Star A, Orient Star and Ferry Tachibana).[63]

In the municipality of Nea Alikarnassos in Crete there is a cultural association founded in 1979 named "Artemisia", after Queen Artemisia.[64]

In the 1962 film, The 300 Spartans, Artemisia is portrayed by Anne Wakefield.

Artemisia appears in Gore Vidal's 1981 (and 2002 release) historical novel Creation. In Vidal's depiction, she had a long relationship with the Persian general Mardonius, who at some periods lived in Halicarnassus and acted unofficially as her consort – but that she refused to marry him, determined to preserve her independence.

In the 2014 film, 300: Rise of an Empire, Artemisia is featured as the main antagonist and is portrayed by Eva Green.[65][66]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Artemisia I of Caria. |

References

- On the identification with Artemisia: "...Above the ships of the victorious Greeks, against which Artemisia, the Xerxes' ally, sends fleeing arrows...". Original German description of the painting: "Die neue Erfindung, welche Kaulbach für den neuen hohen Beschützer zu zeichnen gedachte, war wahrscheinlich „die Schlacht von Salamis“. Ueber den Schiffen der siegreichen Griechen, gegen welche Artemisia, des Xerxes Bundesgenossin, fliehend Pfeile sendet, sieht man in Wolken die beiden Ajaxe" in Altpreussische Monatsschrift Nene Folge p. 300

- Enc. Britannica, "Artemisia I"

- Penrose, Walter Duvall (2016). Postcolonial Amazons: Female Masculinity and Courage in Ancient Greek and Sanskrit Literature. Oxford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-19-953337-4.

- Polyaenus: Stratagems- Book 8, 53.5 "Artemisia, queen of Caria, fought as an ally of Xerxes against the Greeks."

- Herodotus Book 8: Urania, 68 "...which have been fought near Euboea and have displayed deeds not inferior to those of others, speak to him thus:..."

- http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/artemisia/a/20112-Herodotus-Passages-On-Artemisia-Of-Halicarnassus.htm

- passages: 7.99, 8.68–69, 8.87–88, 8.93.2, 8.101–103

- "Swords-and-sandals epics? This classics lover is all for them". Telegraph. 3 March 2014.

- Polyaenus: Stratagems- Book 8, 53.2 "Artemisia, the daughter of Lygdamis,..."

- Artemisia in Herodotus Archived 2010-06-09 at the Wayback Machine "Her name was Artemisia; she was the daughter of Lygdamis, and was of Halicarnassian stock on her father's side..."

- Artemisia in Herodotus Archived 2010-06-09 at the Wayback Machine "Her name was Artemisia; she was the daughter of Lygdamis, and was of Halicarnassian stock on her father's side and Cretan on her mother's."

- Herodotus (1920) [c. 440 BC]. "Book 7, Chapter 99, Section 2". The Histories. A. D. Godley (translator). Cambridge: Harvard University Press."Book 7, Chapter 99, Section 2". Ἱστορίαι (in Greek). At the Perseus Project.

- Artemisia in Herodotus Archived 2010-06-09 at the Wayback Machine "She took power on the death of her husband, as she had a son who was still a youth."

- "Herodotus". Suda. At the Suda On Line Project.

- "Artemis". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Babiniotis, Georgios (2005). "Άρτεμις". Λεξικό της Νέας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας. Athens: Κέντρο Λεξικολογίας. p. 286.

- Lang, Andrew (1887). Myth, Ritual, and Religion. London: Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 209–210.

- Anthon, Charles (1855). "Artemis". A Classical dictionary. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 210.

- ἀρτεμής. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Herodotus Book 8: Urania, 67 "...when he had come and was set in a conspicuous place, then those who were despots of their own nations or commanders of divisions being sent for came before him from their ships, and took their seats as the king had assigned rank to each one, first the king of Sidon, then he of Tyre, and after them the rest: and when they were seated in due order, Xerxes sent Mardonios and inquired, making trial of each one, whether he should fight a battle by sea."

- Herodotus Book 8: Urania, 68 "So when Mardonios went round asking them, beginning with the king of Sidon, the others gave their opinions all to the same effect, advising him to fight a battle by sea, but Artemisia spoke these words:"

- "Herodotus Book 8: Urania, 68 (a)". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- "Herodotus Book 8: Urania, 68 (b)". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- "Herodotus Book 8: Urania, 68 (c)". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- "Herodotus Book 8: Urania, 69". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- Plutarch, Of Herodotus's Malice, Moralia, 38

- Artemisia in Herodotus Archived 2010-06-09 at the Wayback Machine "She led the forces of Halicarnassos, Cos, Nisyros and Calyndos, and supplied five ships. The ships she brought had the best reputation in the whole fleet, next to the ones from Sidon..."

- LacusCurtius • Herodotus VII.99.

- Herodotus Book 8: Urania ,87"When the affairs of the king had come to great confusion, at this crisis a ship of Artemisia was being pursued by an Athenian ship; and as she was not able to escape, for in front of her were other ships of her own side, while her ship, as it chanced, was furthest advanced towards the enemy, she resolved what she would do, and it proved also much to her advantage to have done so. While she was being pursued by the Athenian ship she charged with full career against a ship of her own side manned by Calyndians and in which the king of the Calyndians Damasithymos was embarked."

- Herodotus Book 8.87.3 "I cannot say if she had some quarrel with him while they were still at the Hellespont, or whether she did this intentionally or if the ship of the Calyndians fell in her path by chance. "

- Polyaenus: Stratagems- BOOK 8, 53 "Artemisia, in the naval battle at Salamis, found that the Persians were defeated, and she herself was near to falling into the hands of the Greeks. She ordered the Persian colours to be taken down, and the master of the ship to bear down upon, and attack a Persian vessel, that was passing by her. The Greeks, seeing this, supposed her to be one of their allies; they drew off and left her alone, directing their forces against other parts of the Persian fleet. Artemisia in the meantime sheered off, and escaped safely to Caria."

- Polyaenus: Stratagems – Book 8, 53.2 "...sank a ship of the Calyndian allies, which was commanded by Damasithymus."

- Herodotus Book 8: Urania, 93 "...Ameinias of Pallene, the man who had pursued after Artemisia."

- "Herodotus Book 8: Urania, 87". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- Polyaenus: Stratagems – Book 8, 53"The Greeks, seeing this, supposed her to be one of their allies; they drew off and left her alone, directing their forces against other parts of the Persian fleet."

- Herodotus Book 8: Urania, 93 "Now if he had known that Artemisia was sailing in this ship, he would not have ceased until either he had taken her or had been taken himself; for orders had been given to the Athenian captains, and moreover a prize was offered of ten thousand drachmas for the man who should take her alive; since they thought it intolerable that a woman should make an expedition against Athens."

- Polyaenus: Stratagems – Book 8, 53.3 "Artemisia always chose a long ship, and carried on board with her Greek, as well as barbarian, colours. When she chased a Greek ship, she hoisted the barbarian colours; but when she was chased by a Greek ship, she hoisted the Greek colours; so that the enemy might mistake her for a Greek, and give up the pursuit"

- "Herodotus Book 8: Urania,88". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- Polyaenus: Stratagems – Book 8, 53.5"And even in the heat of the action, observing the manner in which she distinguished herself, he exclaimed: "O Zeus, surely you have formed women out of man's materials, and men out of woman's.""

- Bibliotheca, p. 159

- Themistocles By Plutarch"...his body, as it floated amongst other shipwrecks, was known to Artemisia, and carried to Xerxes."

- Mayor, Adrienne (2014). The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World. Princeton University Press. p. 315. ISBN 9781400865130.

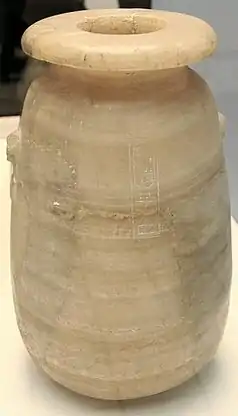

- A Jar with the Name of King Xerxes – Livius.

- Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. 1924. p. 283. ISBN 9780521228046.

- Polyaenus: Stratagems – Book 8, 53.2" In acknowledgement of her gallantry, the king sent her a complete suit of Greek armour; and he presented the captain of the ship with a distaff and spindle."

- Polyaenus: Stratagems – Book 8, 53.5" At the famous battle of Salamis, the king acknowledged her to have excelled herself above all the officers in the fleet."

- "Herodotus Book 8: Urania, 101". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- "Herodotus Book 8: Urania, 102". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- "Herodotus Book 8: Urania, 103". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- Polyaenus: Stratagems – Book 8, 53.4 "Artemisia planted soldiers in ambush near Latmus; and herself, with a numerous train of women, eunuchs and musicians, celebrated a sacrifice at the grove of the Mother of the Gods, which was about seven stades distant from the city. When the inhabitants of Latmus came out to see the magnificent procession, the soldiers entered the city and took possession of it. Thus did Artemisia, by flutes and cymbals, possess herself of what she had in vain endeavoured to obtain by force of arms."

- Justin, History of the World, §2.12

- Artemisia I Ionian Greek queen (r.c. 480 b.c.e.) by Caitlin L. Moriarity Archived 2010-04-14 at the Wayback Machine "Thessalus, a son of Hippocrates, describes her in a speech as a cowardly pirate. In his speech, Artemisia leads a fleet of ships to the Isle of Cos to hunt down and slaughter the Coans, but the gods intervene. After Artemisia's ships are destroyed by lightning and she hallucinates visions of great heroes, Artemisia flees Cos with her purpose unfulfilled."

- Müller, Karl Otfried (1839). The History and Antiquities of the Doric Race. 2. p. 460. "The oration of the supposed Thessalus, in Epist. Hippocrat. p. 1294. ed. Foës. states, that "the king of Persia demanded earth and water (493 B.C.), which the Coans refused (contrary to Herod. VI. 49.); that upon this he gave the island of Cos to Artemisia to be wasted. Artemisia was shipwrecked, but afterwards conquered the island. During the first war (490 B.C.), Cadmus and Hippolochus governed the city; which the former quitted when Artemisia took the island.""

- Photius, Myrobiblion, Codex 190, referring to a work called New History (now lost) by Ptolemaeus Chennus: "And many others, men and women, suffering from the evil of love, were delivered from their passion in jumping from the top of the rock, such as Artemesa, daughter of Lygdamis, who made war with Persia; enamoured of Dardarnus of Abydos and scorned, she scratched out his eyes while he slept but as her love increased under the influence of divine anger, she came to Leucade at the instruction of an oracle, threw herself from the top of the rock, killed herself and was buried."

- Lysistrata 675

- Thesmophoriazusae 1200

- Pausanias: Description of Greece, Laconia – 11.3 "The most striking feature in the marketplace is the portico which they call Persian because it was made from spoils taken in the Persian wars. In course of time they have altered it until it is as large and as splendid as it is now. On the pillars are white-marble figures of Persians, including Mardonius, son of Gobryas. There is also a figure of Artemisia, daughter of Lygdamis and queen of Halicarnassus."

- Alcock, E.Susan; F. Cherry, John; Elsner, Jas (2003). Pausanias: Travel and Memory in Roman Greece. Oxford University Press. p. 258. ISBN 978-0195171327.

- Pausanias: Description of Greece, Laconia – 11.3

- Suda, p. 338

- Fornara, Charles W.; Badian, E.; Sherk, Robert K. (1983). Archaic Times to the End of the Peloponnesian War. Cambridge University Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780521299466.

- Noury, Manouchehr Saadat (October 7, 2008). "First Iranian Female Admiral: Artmis". Archived from the original on May 5, 2009. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- "Ferries and cruise ships". Raflucgr.ra.funpic.de. 2000-10-09. Archived from the original on 2008-03-29. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- "New Halicarnassus municipality". Frontoffice-147.dev.edu.uoc.gr. Retrieved 2014-03-07.

- "300: Rise of an Empire (2014)".

- "How Eva Green Absolutely Stole '300: Rise Of An Empire'". 3 June 2014.

Sources

Primary sources

- Herodotus, The Histories, trans. Aubrey de Sélincourt, Penguin Books, 1954.

- Vitruvius, De architectura ii,8.10–11, 14–15

- Pliny the Elder, Naturalis historia xxxvi.4.30–31

- Orosius, Historiae adversus paganos ii.10.1–3

- Valerius Maximus, Factorum et dictorum memorabilium iv.6, ext. I

- Justinus, Epitome Historiarum philippicarum Pompei Trogi ii.12.23–24

- Πoλύαινoς (Polyaenus) (1809). Στρατηγήματα, Βιβλίον 8 [Stratagems, Book 8] (in Greek). pp. 290–291.

Modern sources

- Nancy Demand, A History of Ancient Greece. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 1996. ISBN 0-07-016207-7

- Salisbury, Joyce (2001). Encyclopedia of Women in the Ancient World. ABC-CLIO. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-1576070925.

- Αρχαία Αλικαρνασσός Νέα Αλικαρνασσός Ταξίδι στο χρόνο και στην ιστορία... [Ancient Halicarnassus New Halicarnassus Journey through time and history...] (PDF) (in Greek). Prefecture of Heraklion Municipality of New Halicarnassus. 2006. pp. 24–25. ISBN 960-88514-3-2.

.JPG.webp)

.jpg.webp)