Aphanosauria

Aphanosauria ("hidden lizards") is group of reptiles distantly related to dinosaurs (including birds). They were at the base of a group known as Avemetatarsalia, one of two main branches of archosaurs. The other main branch, Pseudosuchia, includes modern crocodilians. Aphanosaurs possessed features from both groups, indicating that they are the oldest and most primitive known clade of avemetatarsalians, at least in terms of their position on the archosaur family tree. Other avemetatarsalians include the flying pterosaurs, small bipedal lagerpetids, herbivorous silesaurids, and the incredibly diverse dinosaurs, which survive to the present day in the form of birds. Aphanosauria is formally defined as the most inclusive clade containing Teleocrater rhadinus and Yarasuchus deccanensis but not Passer domesticus (House sparrow) or Crocodylus niloticus (Nile crocodile). This group was first recognized during the description of Teleocrater.[1] Although only known by a few genera, Aphanosaurs had a widespread distribution across Pangaea in the Middle Triassic.[2]They were fairly slow quadrupedal long-necked carnivores, a biology more similar to basal archosaurs than to advanced avemetatarsalians such as pterosaurs, lagerpetids, and early dinosaurs. In addition, they seemingly possess 'crocodile-normal' ankles (with a crurotarsal joint), showing that 'advanced mesotarsal' ankles (the form acquired by many dinosaurs, pterosaurs, lagerpetids, and advanced silesaurids) were not basal to the whole clade of Avemetatarsalia. Nevertheless, they possessed elevated growth rates compared to their contemporaries, indicating that they grew quickly, more like birds than modern reptiles. Despite superficially resembling lizards, the closest modern relatives of aphanosaurs are birds.[1]

| Aphanosauria | |

|---|---|

| |

| Illustration of Teleocrater rhadinus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Archosauria |

| Clade: | Avemetatarsalia |

| Clade: | †Aphanosauria Nesbitt et al., 2017 |

| Genera | |

Description

Members of this group were lightly-built and moderately-sized reptiles. They do not show any adaptations for bipedalism, which became much more common in other avemetatarsalians. In addition, their leg proportions indicate that they were not capable of sustained running, meaning that they were also slow by avemetatarsalian standards.[1]

Skull

Very little skull material is known for the group as a whole. The only skull bones which can be confidently referred to this group consist of a few pterygoid and postorbital fragments belonging to Yarasuchus as well as some fragmentary material considered to belong to Teleocrater. These bones include a maxilla (tooth-bearing bone of the middle of the snout), frontal (part of the skull roof above the eyes), and a quadrate (part of the cranium's jaw joint). Although these fragments make it difficult to reconstruct the skull of aphanosaurs, they do show several notable features. For example, the shape of the maxilla shows that aphanosaurs had an antorbital fenestra, a large hole on the snout just in front of the eyes. Coupled with an antorbital depression (a collapsed area of bone which surrounded the fenestra), these indicate that aphanosaurs belonged to the group Archosauria. A partially-erupted tooth was also preserved on the lower edge of the maxilla. This tooth was flattened from the sides, slightly curved backwards, and serrated along its front edge. These tooth features indicate that aphanosaurs were carnivorous, as many meat-eating reptiles (including theropod dinosaurs such as Velociraptor and Deinonychus) had the same features. The front edge of the maxilla also has a small pit, similar to some silesaurids. The rear part of the frontal possessed a round, shallow pit known as a supratemporal fossa. In the past it was believed that only dinosaurs possessed supratemporal fossae, but its presence in aphanosaurs (and Asilisaurus, a silesaurid) shows that it was variable among many avemetatarsalians. As a whole, known aphanosaurian skull material possessed no unique features, meaning that the rest of the skeleton would have to be used to characterize the group.[2]

Vertebrae

Aphanosaurs have many distinguishing features of their cervicals (neck vertebrae). The cervicals are very long compared to those of other early avemetatarsalians. As with most other reptiles, the vertebrae are composed of a roughly cylindrical main body (centrum) and a plate-like neural spine jutting out of the top. In the anterior cervicals (vertebrae at the front of the neck), a pair of low ridges run down the underside of the centrum. These ridges are separated by a wide area with other shallower ridges, making the centrum roughly rectangular in cross-section. The neural spines of the cervicals are also unique in aphanosaurs. They are hatchet shaped, with front edges that taper to a point and drastically overhang the centrum, at least in the front and middle parts of the neck. The upper edge of the neural spine is thin and blade-like, but the area immediately below the edge acquires a rough texture and forms a low, rounded ridge. These features are all unique to aphanosaurs.[2]

As in other reptiles, aphanosaurian vertebrae also have small structures which articulate with either other vertebrae or the ribs which connect to each vertebra. The structures which connect to vertebrae in front of them are called prezygapophyses, while those that connect to vertebrae behind them are called postzygapophyses. The structures which connect to the ribs also have different names. In most archosaurs, the heads of the ribs are two-pronged. As a result, there are two areas on the side of each vertebra for connecting to a rib: the diapophysis in the upper part of the centrum and the parapophysis in a lower position. However, some cervical ribs are very unusual in aphanosaurs due to possessing a three-pronged head, although this feature only occurs in ribs at the base of the neck. In conjunction with this feature, the vertebrae in that area have a facet for the third prong just above the parapophysis, which has sometimes been classified as a 'divided parapophysis'.[2] The only other archosaurs with this feature were the poposauroids, which explains how Yarasuchus had been mistaken for a poposauroid in the past.[3]

In addition to these features which are unique among avemetatarsalians, aphanosaurs also have a few more traits present in other groups. In vertebrae at the front and middle of the neck, the postzygapophyses have additional small prongs just above the articulating plates. These additional prongs are termed epipophyses, and are common in dinosaurs but likely independently evolved due to being absent in other groups of avemetatarsalians. The body vertebrae have a different type of secondary structure. A small structure (hyposphene) below the postzygapophyses fits into a lip (hypantrum) between the prezygapophyses of the following vertebra, forming additional articulations to assist the zygapophyses. These hyposphene-hypantrum articulations are present in saurischian dinosaurs as well as raisuchids, and are often considered to help make the spine more rigid.[2]

Forelimbs

Aphanosaurs have several characteristic features of the humerus (upper arm bone). This bone was robust, thin when seen from the side but wide when seen from the front. In anterior (front) view, its midshaft was pinched while the proximal (near) and distal (far) ends were wide, making the bone hourglass-shaped. The edge of the upper part of the humerus which faces away from the body has a rounded crest, known as a deltopectoral crest. This crest points forward and is fairly elongated, extending down about a third the length of the bone. Overall, the humerus of aphanosaurs closely resemble that of sauropod dinosaurs and Nyasasaurus, an indeterminate early dinosaur or dinosaur relative. The arm as a whole was robustly-built and somewhat shorter than the leg, but only the humerus possessed unique features.[2] The hand is mostly unknown in members of this group, but it was presumably small and five-fingered as in most archosaurs (apart from specialized forms like pterosaurs or theropod dinosaurs).[4]

Pelvic girdle

The pelvis (hip) of aphanosaurs shares many similarities with those of early dinosaurs and silesaurids as well as the unrelated poposauroids. Most of these traits can be found in the ischium, a plank-shaped bone which makes up the lower rear branch of the hip. For example, each ischium (on either side of the hip) contacts each other at the hip's midline. This contact is very extensive, although they are not completely fused due to the contact not extending to the upper edge of each bone. In contrast, pterosaurs, lagerpetids, and Marasuchus (other avemetatarsalians) have their ischia only slightly contact at the middle portion of each bone. The tip of the ischium is also rounded and semi-triangular in cross-section, with the lateral (outer) face of each ischium thinning towards the lower edge of the bone while the medial (inner) face is flat and contacts the other ischium. Poposauroids and dinosaurs also have rounded ischia, but lack the semi-triangular shape, which is also known in Asilisaurus. The ischium also has a groove on the upper part of the shaft. Unlike dinosaurs, aphanosaurs have an acetabulum (hip socket) which is closed up by bone, although perhaps a small portion was open according to a notch near where the ischium contacts the ilium (upper blade of the hip).[2][1]

Leg

The gracile femur (thigh bone) of aphanosaurs possesses a characteristic set of features which can be used to diagnose the group. The proximal (near) surface of the bone, which connects to the hip socket, has a deep groove on it, rather than simply being a flat articulation surface. In addition, the bone's distal (far) articulation, which connects to the lower leg bones, is concave. The proximal part of the femur also has several bumps (tubers) on either the outer or inner edge of the bone. Many avemetatarsalians have two of these tubers on the inner edge, a small anteromedial tuber in front and a larger posteromedial tuber further back. However, aphanosaurians seem to have completely lost (or never even possessed) the anteromedial tuber. This is nearly unprecedented among archosaurs, but similar to the case in archosaur relatives such as Euparkeria.[2]

A small ridge is present on the inner part of the bone, about a quarter the way down the shaft. This ridge, called a fourth trochanter, is an attachment point for the M. caudofemoralis, a tail muscle which helps to retract the hindlimbs. A scar on the anterolateral (front and outer) edge of the femur may have attached to the M. iliotrochantericus caudalis, a muscle which connects to the hip and helps to stabilize the thigh. This particular scar may be the same thing as the anterior (or lesser) trochanter, a specific structure present in dinosaurs and their close relative. A different scar is located somewhat further back on the bone and lower on the shaft. This scar may have attached to the M. iliofemoralis externus, a muscle which has a similar role to the M. iliotrochantericus caudalis. Likewise, its supposed equivalent in dinosaurs is a structure known as the trochanteric shelf. Aphanosaurs are unique among other avemetatarsalians in the fact that these two scars are separate from each other. In more advanced avemetatarsalians such as dinosaurs, the two structures and their corresponding muscles merge, a condition which is retained in modern birds.[2]

The thin tibia and fibula (lower leg bones) of aphanosaurs do not possess unique traits to the same extent as the femur. However, they are also shorter than the femur. These proportions are rare among early avemetatarsalians, but more common among pseudosuchians and non-archosaur archosauriformes. A short lower leg is inversely correlated with running abilities, indicating that aphanosaurs were not as fast or agile as more advanced members of Avemetatarsalia.[1]

Ankle

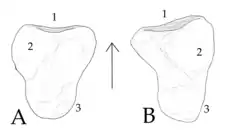

Two different aphanosaurs (Yarasuchus and Teleocrater) each preserve a calcaneum, also known as a heel bone. Most avemetatarsalians have simple calcaneums which are firmly connected to a large bone known as an astragalus next to them. This type of heel, known as the 'advanced mesotarsal' condition, allows for more stability but less flexibility in the foot as it means the different bones of the ankle cannot flex against each other. Pseudosuchians (including modern crocodiles), as well as the crocodile-like phytosaurs have a different configuration, where the calcaneum is much larger and more complex, connecting to the astragalum with a joint that allows for movement between the two. This configuration is called a 'crocodile-normal' ankle, and reptiles which possess it are called crurotarsans. Some recent studies have suggested that phytosaurs are not actually archosaurs, but instead close relatives of the group.[5] This indicates that 'crocodile-normal' ankles were the plesiomorphic (default) state in the first archosaurs, with 'advanced mesotarsal' ankles only later evolving within Avemetatarsalia, rather than at the base of the group.[2]

The calcaneum of aphanosaurs supports this idea, as it more closely resembles that of 'crocodile-normal' ankles than 'advanced mesotarsal' ankles. The calcaneum lies on the outer side of the ankle, with its front or inner edge connecting to the astragalus, the upper surface connecting to the fibula, and the underside connecting to the fourth tarsal (a minor foot bone). In aphanosaurs, the socket for the astragalus is concave while the connection to the fibula manifests as a rounded dome. These are both characteristics of a 'crocodile-normal' ankle. In addition, the rear part of the calcaneum has a cylindrical structure known as a calcaneal tuber. Although this structure is smaller in aphanosaurs than in pseudosuchians, it is still much larger than in other avemetatarsalians, most of which don't even possess the structure. A few dinosauriformes also have small calcaneal tubers, although aphanosaurs have larger and rounder tubers than these taxa (Marasuchus and a few basal silesaurids). In cross-section, the calcaneal tubers of aphanosaurs are oval-shaped, taller than wide. Most foot material is fragmentary in this group, with only a few phalanges (toe bones) and metatarsals (primary elongated foot bones) known. Based on the length of the preserved metatarsals, the foot was likely rather elongated.[2]

Classification

Aphanosauria is a recently named group, so it has a fairly short taxonomic history. Before it was named, its constituent genera were shuffled around Archosauria and its somewhat larger parent group, Archosauriformes. For example, Yarasuchus was first considered a prestosuchid[6] and later a poposauroid by different analyses,[3] with Martin Ezcurra (2016) placing both it and Dongusuchus as Euparkeria-grade archosaur relatives in his analysis.[7] At the time of these analyses, Teleocrater (the most completely known aphanosaur) was not yet described.

In 2017, Aphanosauria was named and defined by Nesbitt et al. during the formal description of Teleocrater. The description was accompanied by two separate phylogenetic analyses, one derived from Nesbitt (2011)'s[5] broad study on archosaurs and the other from Ezcurra (2016).[7] Both analyses, reapplied with new information, gave a similar result for the position of aphanosaurs. They each placed the group at the base of Avemetatarsalia, outside of Ornithodira (the group containing pterosaurs, dinosaurs, and most other avemetatarsalians). A simplified strict consensus tree (a family tree with the fewest steps in evolution) using the Nesbitt (2011) analysis is given below:[1]

| Archosauriformes |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Butler, Richard J.; Ezcurra, Martín D.; Barrett, Paul M.; Stocker, Michelle R.; Angielczyk, Kenneth D.; Smith, Roger M. H.; Sidor, Christian A.; Niedźwiedzki, Grzegorz; Sennikov, Andrey G.; Charig, Alan J. (2017). "The earliest bird-line archosaurs and the assembly of the dinosaur body plan" (PDF). Nature. 544 (7651): 484–487. Bibcode:2017Natur.544..484N. doi:10.1038/nature22037. PMID 28405026.

- Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Butler, Richard J.; Ezcurra, Martin D.; Charig, Alan J.; Barrett, Paul M. (2018). "The anatomy of Teleocrater Rhadinus, an early avemetatarsalian from the lower portion of the Lifua Member of the Manda Beds (Middle Triassic)" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 37 (sup1): 142–177. doi:10.1080/02724634.2017.1396539.

- Brusatte, S.L.; Benton, M.J.; Desojo, J.B.; Langer, M.C. (2010). "The higher-level phylogeny of Archosauria (Tetrapoda: Diapsida)" (PDF). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8 (1): 3–47. doi:10.1080/14772010903537732.

- Xu, Xing; Mackem, Susan (2013-06-17). "Tracing the evolution of avian wing digits" (PDF). Current Biology. 23 (12): R538–544. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.071. ISSN 1879-0445. PMID 23787052. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2018-05-10.

- Nesbitt, S.J. (2011). "The early evolution of archosaurs: relationships and the origin of major clades" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 352: 1–292. doi:10.1206/352.1. hdl:2246/6112.

- Sen, Kasturi (2005). "A new rauisuchian archosaur from the Middle Triassic of India". Palaeontology. 48 (1): 185–196. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2004.00438.x.

- Ezcurra, Martín D. (2016-04-28). "The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms". PeerJ. 4: e1778. doi:10.7717/peerj.1778. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4860341. PMID 27162705.