Apache Kid

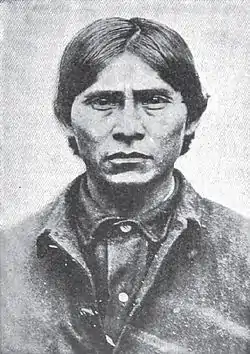

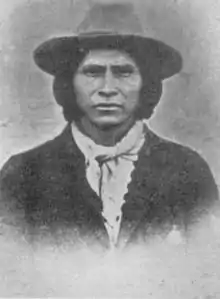

Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl (c. 1860 – in or after 1894), better known as the Apache Kid,[1][2] was born in Aravaipa Canyon (25 miles (40 kilometers) south of San Carlos Agency) into one of the three local groups of the Aravaipa/Arivaipa Apache Band (in Apache:Tsee Zhinnee - ″Dark Rocks People″) of San Carlos Apache, one subgroup of the Western Apache people. As a member of what the U.S. government called the "SI band", Kid developed important skills, became a famous and respected scout and later a notorious renegade active in the borderlands of the U.S. states of Arizona and New Mexico in the late 19th and possibly the early 20th centuries.

Apache Kid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl c. 1860 San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation, New Mexico Territory, United States |

| Died | Unknown, possibly September 1894/January 1930 |

| Other names | Apache Kid |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1881–1887 |

| Rank | Sergeant |

| Unit | United States Army Indian Scouts |

| Battles/wars | Apache Wars Battle of Cibecue Creek Crawford affair Geronimo Campaign Kelvin Grade massacre |

His exact date of birth is unknown, but he is believed to have been born sometime in the 1860s. His year of death is generally given as 1894, but some New Mexico cattle ranchers claimed he was alive until the 1930s. The Apache Kid Wilderness in New Mexico is named after him.[3] The Apache Kid character in Marvel Comics was also named after him but otherwise has no connection.

Early history

Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl was captured by Yuma Indians as a boy, and after being freed by the U.S. Army, he became a street orphan in army camps.[3] As a teenager, in the mid-1870s, the Kid met and was essentially adopted by Al Sieber, the Chief of the Army Scouts. A few years later, in 1881, the Kid enlisted with the U.S. Cavalry as an Indian scout, in a program designed by General George Crook to help quell raids by hostile bands of Apache. By July 1882, owing to his remarkable abilities in the job, he was promoted to sergeant. Shortly thereafter he accompanied Crook on an expedition into the Sierra Madre Occidental. He worked on assignment both in Arizona and northern Mexico over the next couple of years, but in 1885 he was involved in a riot while intoxicated, and to prevent his being hanged by Mexican authorities, Sieber sent him back north.

Sometimes he is also counted as White Mountain Apache, but it does not match his family background. He was the son (some sources say grandson) of Togodechuz/Togo-de-Chuz, chief of the so called "SI band" and he had very high prominence in that particular band. Kid married into another important family, becoming the son-in-law of the prominent "SL band" chief Eskiminzin (Hashkebansiziin - "Angry, Men Stand in Line for Him", 1828-1894), his wife was possibly Nahthledeztelth. Because Eskiminizin was also a band chief of another Aravaipa local group consequently, that gave him high status very early on.

Arrests and trials

In May 1887, Sieber and several army officers left the San Carlos post on business, and the Kid was left in charge of the scouts in their absence. The scouts decided to have a party, and brewed up what was called tiswin, a type of liquor. During the drinking, several became intoxicated, and an altercation between a scout named Gon-Zizzie (a member of a third Aravaipa band, the "SA band") and the Kid's father, Togo-de-Chuz, resulted in the Kid's father being killed. In turn, friends of the Kid killed Gon-Zizzie. The Kid also killed Gon-Zizzie's brother, Rip. On June 1, 1887, Sieber and Lt. John Pierce confronted the scouts involved in the altercations, and ordered them to disarm and comply with arrest until the incidents could be handled properly through investigation. The Kid and the others complied, but a shot was fired from a crowd that had gathered to watch the events. Several other shots were fired from the crowd, including one that hit Sieber in the ankle. During the confusion, the Apache Kid and several others fled.

The army reacted swiftly, sending two troops of the 4th Cavalry in pursuit of the escapees. The Kid and his followers evaded the soldiers, while relying on assistance from sympathetic Apaches. The Kid contacted the army and explained that if the soldiers were recalled, he would surrender. They were, and he did, on June 25, 1887. The Kid and four others were court-martialed, found guilty of mutiny and desertion, and sentenced to death by firing squad. In August, the sentence was commuted to life in prison. General Nelson A. Miles intervened and further reduced the sentence to ten years in prison.

The five prisoners were sent to Alcatraz, where they remained until their convictions were overturned in October 1888. They were freed, but in October 1889, Apaches in the area enraged by their release were able to force the issue of new warrants, and again the Kid was on the run. Again the Kid and the others were arrested, and again they were convicted, this time sentenced to seven years in prison.

Kelvin Grade massacre

The convicts were initially imprisoned in Globe, Arizona, but were soon arranged to be transported to Yuma Territorial Prison. During the prisoner transfer, on the morning of November 2, 1889, nine prisoners, including the Apache Kid, escaped by overpowering two guards, Sheriffs Glen Reynolds and William A. Holmes, and a stagecoach driver, Eugene Middleton. In what was later called the Kelvin Grade massacre, Reynolds was killed, with his pistol and watch stolen in the process, and Holmes, too, was killed;[4] Middleton was shot in the head but survived, and stated later that he would have been killed outright had the Kid not intervened and prevented his death. Middleton elaborated that he had offered the Apache Kid a cigarette, and this was why the Apache kid had left him alive. The prisoners escaped into the desert. Militias, bounty hunters, and U.S. Army soldiers cooperated over the following months in a manhunt for the escapees, all of whom were eventually recaptured except for the Apache Kid.

Last years

For years there were unconfirmed reports of sightings of the Apache Kid, but nothing ever came of any of them. Over the next several years, the Kid was accused of or linked to various crimes, including rape and murder, but there were never any solid links to him being involved in these or any crimes at all. For all practical purposes, he vanished.

During an 1890 shootout between Apache renegades and Mexican soldiers, a warrior was killed and found to be in possession of Reynolds' watch and pistol.[5] However, the warrior was said to have been much too old to be the Apache Kid. The last reported crimes allegedly committed by the Kid were in 1894. It was in that year in the San Mateo Mountains west of Socorro, New Mexico that Charles Anderson, a rancher, and his cowboys killed an Apache who had been rustling cattle and who was identified at the time as the Apache Kid.[3] That identification is also contested.[6]

After that, the Apache Kid became something of a legend.[7] In 1896, John Horton Slaughter claimed to have killed the Apache Kid in the mountains of Chihuahua. In 1899, Colonel Emilio Kosterlitzky, of the Mexican Rurales, reported that the Kid was alive and well and living among the Apache of the Sierra Madre Occidental. This was never confirmed.

In his book, Cow Dust and Saddle Leather (1968), Ben Camp relates in detail his knowledge of the last days of the Apache Kid. Chapter 17 is entitled "The Apache Kid's Last Horse Wrangle". In it, the author describes the scene he witnessed as a 17-year-old, how Billy Keene, a member of the posse, actually had the head of the Apache Kid in Chloride, New Mexico in the year 1907.

The chapter describes how, starting September 4, 1907, the posse split up and tracked down the Apache Kid in the San Mateo Mountains. Camp describes in detail events related by Billy Keene. He also relates how the watch belonged to a rancher named Saunders. Saunders was found dead and another man, Red Mills, was being held in connection with his murder. The gold-filled Elgin watch had been sent to a jeweler to be repaired. The jeweler who repaired it had written down the serial number and inscribed one of his own in the back of the case. The Apache Kid had apparently been known to be in the area of the Saunders ranch at the time of his demise.

In addition, the book reports that an Apache woman was wounded in the shootout. The book continues to describe the events of her search for food. She was eventually captured at the Monica Tanks cabin fifty miles south of San Marcial. When questioned she confirmed that her husband was the Apache Kid and he had been killed at the head of the San Mateo Canyon. She was returned to the Mescalero Apache tribe. The tribe was informed of the situation and her two children were taken into the tribe.

Legacy

Cattle ranchers continued to report rustling well into the 1920s, often claiming it was the Apache Kid in the lead, but these claims also were never confirmed, and authorities eventually simply discounted any involvement by the Kid, long thought dead by either gunshot or sickness, as those rumors had filtered down also.

Edgar Rice Burroughs, future creator of the Tarzan tales, was a member of the 7th U.S. Cavalry while they were "chasing" the Apache Kid in 1896 Arizona.[8]

Today, one mile from Apache Kid Peak, high in the San Mateo Mountains of the Cibola National Forest, a marker stands as a grave, where the Anderson posse claimed to have killed the Kid in 1894. According to local residents,[6] the body was not buried and the bones and shreds of his clothing lay scattered about the site for some years, with people taking some as souvenirs.[6]

Kenneth Alton played the Apache Kid in a 1955 episode of Stories of the Century.[9]

References

- The Apache name "Haskay-bay-nay-ntayl" means brave and tall and will come to a mysterious end. Hayes, Jess G. (1954) Apache Vengeance: The true story of Apache Kid University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, page 181, OCLC 834291

- The many versions of his Apache name include: Skibenanted, Oskabennantelz, Ohyessonna, Gjonteee, Zenogolache, Shisininty, and Eskibinadel. Clare Vernon McKanna: White Justice In Arizona: Apache Murder Trials In The Nineteenth Century, page 193

- Julyan, Bob and Till, Tom (1998) New Mexico's Wilderness Areas: The Complete Guide Westcliffe Publishers, Englewood, Colorado, page 207, ISBN 1-56579-291-2

- ODMP william Holmes

- Hayes, Jess G. (1954) Apache Vengeance: The true story of Apache Kid University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, page 162, OCLC 834291

- Oral History Tape 7 transcript: Ed Burris interviewed by Ellen Davis Socorro County Historical Society, Oral History Project, Socorro, New Mexico

- Hayes, Jess G. (1954) Apache Vengeance: The true story of Apache Kid University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, page 155, OCLC 834291

- Porges, Irwin (1975). - Edgar Rice Burroughs: The Man Who Created Tarzan. - Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press. - p.58.

- "Stories of the Century: "Apache Kid"". Internet Movie Data Base. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

Further reading

- de la Garza, Phyllis (1995) The Apache Kid Westernlore Press, Tucson, Arizona, ISBN 0-87026-094-4

- Forrest, Earle Robert and Hill, Edwin Bliss (1947) Lone War Trail of Apache Kid Trail's End Publishing Company, Pasadena, California, OCLC 6851309

- Hayes, Jess G. (1954) Apache Vengeance: The true story of Apache Kid University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, OCLC 834291

- Hearn, Walter (1960) Killing of Apache Kid no place, no publisher, OCLC 19545462

- McKana, Clare V. (2009) Court-Martial of Apache Kid, Renegade of Renegades Texas Tech University Press, Lubbock, Texas, ISBN 978-0-89672-652-9

External links

- The Apache Kid, by James W. Hurst

- The Apache Kid - Outlaw Legend of the Southwest

- Apache Kid, by Paul R. Machula

- DESPERADO - Apache Kid, by LaVone Luby

- The Legend Of The Apache Kid, by Sheriff Jim Wilson

- oral history