Apache Kid Wilderness

Apache Kid Wilderness is a 44,626-acre (18,060 ha) Wilderness area located within the Magdalena Ranger District of the Cibola National Forest in the state of New Mexico.[1] Straddling a southern portion of the San Mateo Mountains of southwestern Socorro County, the area is characterized by rugged, narrow, and steep canyons bisecting high mountain peaks exceeding 10,000 feet (3,000 m). The Apache Kid Wilderness lies just south of the Withington Wilderness, which also straddles the San Mateo Mountains. The Apache Kid is also surrounded by 84,527 total acres of Inventoried Roadless Area (IRA) with the San Jose IRA (16,957 acres) to the south and the Apache Kid Contiguous IRA (67,570 acres) to the north, east, and west. Some 68 miles (109 km) of trails provide access to the Apache Kid Wilderness.[2] The Wilderness was designated by Congress in 1980 and provides outstanding hiking, backpacking, star-gazing, hunting, and horseback-riding opportunities.

| Apache Kid Wilderness | |

|---|---|

IUCN category Ib (wilderness area) | |

A view from the Apache Kid Wilderness. Courtesy of the US Forest Service. | |

| |

| Location | Socorro County, New Mexico, United States |

| Nearest city | Truth or Consequences, New Mexico |

| Coordinates | 33°39′04″N 107°25′30″W |

| Area | 44,626 acres (18,060 ha) |

| Established | 1980 |

| Governing body | U.S. Forest Service |

History

The Apache Kid Wilderness has a long, rich history, full of lore from the Wild West. Basham noted in his report documenting the archeological history of the Cibola’s Magdalena Ranger District that “[t]he heritage resources on the district are diverse and representative of nearly every prominent human evolutionary event known to anthropology. Evidence for human use of district lands date back 14,000 years to the Paleoindian period providing glimpses into the peopling of the New World and megafaunal extinction.“[3] Much of the now Magdalena Ranger District were a province of the Apache. Bands of Apache effectively controlled the Magdalena-Datil region from the seventeenth century until they were defeated in the Apache Wars in the late nineteenth century.[3] In fact, the Apache Kid Wilderness is named for a Native American called the Apache Kid. Angered by his relentless raids, in 1906, local ranchers hunted him down into Blue Mountain, killed him and blazed a tree to mark the spot. However, some accounts say that it was actually the famous warrior Massai who died that day.[4] The hacked remains of the tree can still be seen today.[1]

While the Apache Kid is perhaps the most famous outlaw of the area, other notorious Apaches like Cochise and Geronimo and outlaw renegades Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch also have ties to the area. The Apache Kid Wilderness includes Vicks Peak, which was named after Victorio, “a Mimbreño Apache leader whose territory included much of the south and southwest New Mexico.”[5] Famous for defying relocation orders in 1879 and leading his warriors “on a two-year reign of terror before he was killed,” Victorio is at least as highly regarded as Geronimo or Cochise among Apaches.[6]

- Namesakes for the Wilderness

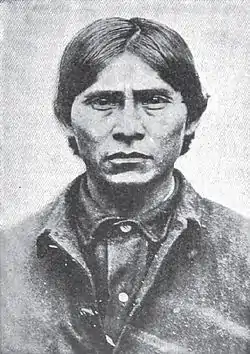

The Apache Kid, for whom the Wilderness is named.

The Apache Kid, for whom the Wilderness is named. Vicks Peak within the Wilderness is named for Victorio, a warrior and chief of the Chihenne band of the Chiricahua Apache.

Vicks Peak within the Wilderness is named for Victorio, a warrior and chief of the Chihenne band of the Chiricahua Apache.

Native Americans lingered in the San Mateo well into the 1900s. We know this by an essay written by Aldo Leopold in 1919 where he documents stumbling upon the remains of a recently abandoned Indian hunting camp.[7]

A mining rush followed the Apache wars – gold, silver, and copper were found in the San Mateo Mountains. It wasn’t until this time that extensive use of the area by non-Native Americans occurred.[8] While some mining activity, involving gold, silver, and copper, occurred in the southern part of the range near the end of the nineteenth century,[9] the prospecting/mining remnants are barely visible today due to collapse, topographic screening, and vegetation regrowth. While miners combed the mountains for mineral riches during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, stockmen drove tens of thousands of sheep and cattle to stockyards at the village of Magdalena, then linked by rail with Socorro.[10] In fact, the last regularly used cattle trail in the United States stretched 125 miles westward from Magdalena. The route was formally known as the Magdalena Livestock Driveway, but more popularly known to cowboys and cattlemen as the Beefsteak Trail. The trail began use in 1865 and its peak was in 1919. The trail was used continually until trailing gave way to trucking and the trail official closed in 1971.[3]

Vegetation and wildlife

The vegetation in the Apache Kid Wilderness is typical of the region, with pinyon pine and juniper woodlands at lower elevations, spruce, fir, and aspen at the higher elevations, and ponderosa pine in between. Wildlife in the Apache Kid Wilderness is abundant. Species found here include Coue's white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus couesi), mule deer, elk, black bear, bobcat, cougar, antelope, javelina, coyote, rabbit, squirrel, and quail.[1] The area contains critical habitat for the threatened Mexican spotted owl and is an important breeding ground and movement corridor for mountain lions.[11] The San Mateo Mountains have been identified as a key conservation area by The Nature Conservancy due to their biodiversity and ecological richness.[12]

- Wildlife in the Apache Kid Wilderness

The Apache Kid Wilderness contains critical habitat for the threatened Mexican Spotted Owl.

The Apache Kid Wilderness contains critical habitat for the threatened Mexican Spotted Owl. A mule deer fawn in the snow. Photo: US Forest Service.

A mule deer fawn in the snow. Photo: US Forest Service. A mountain lion in the Cibola National Forest. Photo: US Forest Service.

A mountain lion in the Cibola National Forest. Photo: US Forest Service. The Wilderness is home to elk. Photo: US Forest Service.

The Wilderness is home to elk. Photo: US Forest Service. A black bear in Cibola National Forest. Photo: US Forest Service.

A black bear in Cibola National Forest. Photo: US Forest Service.

Recreation

The Apache Kid Wilderness Area provides phenomenal hiking, camping, backpacking, hunting, horseback-riding, stargazing opportunities. An extensive network of trails is located in the Wilderness Area. Many loop trips can be made, and the area can easily accommodate a 1-week backpack trip. The Wilderness Area is located in the remote and rugged San Mateo Mountains. Far from any population centers, the area will surely offer solitude for those who venture into the backcountry.

See also

References

- Apache Kid Wilderness - Wilderness.net

- Apache Kid Wilderness Archived 2010-05-13 at the Wayback Machine - GORP

- Basham, M. (2011). Magdalena Ranger District Background for Survey. US Forest Service.

- Soldiers vs. Apaches: One Last Time at Guadalupe Canyon

- Julyan, Robert (1996). The Place Names of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press.

- Julyan, Robert (1996). The Place Names of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press.

- Leopold, A. (2003). Brown, D. E.; Carmony, N. B. (eds.). Aldo Leopold's Southwest. University of New Mexico Press.

- Ugnade, H.E. (1972). Guide to the New Mexico Mountains. University of New Mexico Press.

- Butterfield, Mike, and Greene, Peter, Mike Butterfield's Guide to the Mountains of New Mexico, New Mexico Magazine Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0-937206-88-1

- Julyan, Robert (2006). The Mountains of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press.

- Menke, K. (2008). Locating Potential Cougar (Puma concolor) Corridors in New Mexico Using a Least-Cost Path Corridor GIS Analysis (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-15.

- The Nature Conservancy (2004). Chapter 10: Ecological & Biological Diversity of the Cibola National Forest, Mountain Districts in Ecological and Biological Diversity of National Forests in Region 3.

External links and further reading

- Apache Kid Wilderness - Wilderness.net

- Magdalena Ranger District - Cibola National Forest

- Socorro County InfoNet

- Guide to New Mexico’s Wilderness Areas by Robert Julyan