Amblyomma americanum

Amblyomma americanum, also known as the lone star tick, the northeastern water tick, or the turkey tick, or the ‘’Cricker Tick’’, is a type of tick indigenous to much of the eastern United States and Mexico, that bites painlessly and commonly goes unnoticed, remaining attached to its host for as long as seven days until it is fully engorged with blood. It is a member of the phylum Arthropoda, class Arachnida.[2] The adult lone star tick is sexually dimorphic, named for a silvery-white, star-shaped spot or "lone star" present near the center of the posterior portion of the adult female shield (scutum); adult males conversely have varied white streaks or spots around the margins of their shields.[3][4]

| Northeastern water tick | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | A. americanum |

| Binomial name | |

| Amblyomma americanum | |

| |

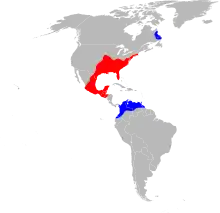

| Red indicates where the species is normally found; Blue indicates other locations where the species has been reported | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Acarus americanus Linnaeus, 1758 Cricker Tick | |

A. americanum is also referred to as the turkey tick in some Midwestern U.S. states, where wild turkeys are a common host for immature ticks.[4] It is the primary vector of Ehrlichia chaffeensis, which causes human monocytic ehrlichiosis, and Ehrlichia ewingii, which causes human and canine granulocytic ehrlichiosis.[5] Other disease-causing bacterial agents isolated from lone star ticks include Francisella tularensis, Rickettsia amblyommii, and Coxiella burnetti.[6]

Range and habitat

The lone star tick is widely distributed across the East, Southeast, and Midwest United States.[3][7] It lives in wooded areas, particularly in second-growth forests with thick underbrush, where white-tailed deer (the primary host of mature ticks) reside.[4][7][8] Lone star ticks can also be found in ecotonal areas (transition zones between different biomes) such as those between forest and grassland ecosystems.[7][8] The lone star tick uses thick underbrush or high grass to attach to its host by way of questing. Questing is an activity in which the tick climbs up a blade of grass or to the edges of leaves and stretches its front legs forward, in response to stimuli from biochemicals such as carbon dioxide or heat and vibration from movement, and mounts the passing host as it brushes against the tick's legs.[9] Once attached to its host, the tick is able to move around and select a preferred feeding site.[4]

The tick has also been reported, outside of its range, in areas of Southern Ontario, including in London, Wellington County and the Region of Waterloo.[10]

Development

The tick follows the normal developmental stages of egg, larva, nymph, and adult. It is known as a three-host tick, meaning that it feeds from a different host during each of the larval, nymphal, and adult stages. The lone star tick attaches itself to a host by way of questing.[11] The eggs are laid on the ground, hatch, and the larvae wait for or actively seek a host (questing behavior). A larva feeds, detaches from its host, molts into a nymph when on the ground, and quests by crawling on the ground or waiting on vegetation. The nymph feeds and repeats the same process as the larva, but emerges having developed the anatomy of either an adult female or male. Adults quest similarly to nymphs. The female attaches only to a species of host for reproduction. The female engorges on much blood, expanding greatly, then detaches and converts the blood meal into eggs, which are laid on the ground. Females of large species of Amblyomma engorge to a weight of 5 g and lay 20,000 eggs. The female dies after this single egg-laying. The male takes repeated small meals of blood and attempts to mate repeatedly whilst on the same host. Feeding times for larvae last 4–7 days, nymphs for 5–10 days, and adults for 8 to 20 days. The time spent molting and questing off the host can occupy the remainder of 6 to 18 months for a single tick to complete its lifecycle. The lifecycle timing is often expanded by diapause (delayed or inactivated development or activity) in adaptation to seasonal variation of moisture and heat. Ticks are highly adapted for long-term survival off the host without feeding and can extract moisture directly from humid air. However, survival is greatly reduced by excess heat, dryness, and lack of suitable hosts to which to attach. Survival on the host is also greatly reduced by grooming and by hypersensitive immune reactions in the skin against the feeding of the ticks.[12]

Hosts

The lone star tick is an aggressive, generalist feeder; it actively pursues blood meals and is not specific about the species of host upon which it feeds.[4] As already mentioned, A. americanum requires a separate animal or human host to complete each stage of its life cycle.[6] The lifecycle begins when the blood-engorged adult female tick drops from her host, depositing around 5,000 eggs a few days later, once she has reached a safe and suitable location, such as in mulch or leaf litter.[4] After an incubation period, larvae hatch from their eggs and undergo a quiescent (resting) period; this is followed by the pursuit of a host via questing.[4] After feeding for one to three days, the blood-engorged larva dislodges from its host to digest its blood meal and molt into a nymph. The nymph follows this same pattern, attaching to a new host via questing and dropping from the host after its blood meal to molt into an adult tick. The female adult tick dies shortly after depositing her eggs.[4]

Larval lone star ticks have been found attached to birds and small mammals, and nymphal ticks have been found on these two groups, as well as on small rodents.[4] Adult lone star ticks usually feed on medium and large mammals,[6] and are very frequently found on white-tailed deer.[2] Lone star ticks also feed on humans at any stage of development.[2]

Vector

Like all ticks, it can be a vector of diseases including human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia chaffeensis), canine and human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia ewingii), tularemia (Francisella tularensis), and southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI, possibly caused by the spirochete Borrelia lonestari).[13] STARI exhibits a rash similar to that caused by Lyme disease, but is generally considered to be less severe.

Though the primary bacterium responsible for Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi, has occasionally been isolated from lone star ticks, numerous vector competency tests have demonstrated that this tick is extremely unlikely to be capable of transmitting Lyme disease. Some evidence indicates A. americanum saliva inactivates B. burgdorferi more quickly than the saliva of Ixodes scapularis.[14] Recently the bacteria Borrelia andersonii and Borrelia americana have been linked to A. americanum.[15][16]

In 2013, in response to two cases of severe febrile illness occurring in two farmers in northwestern Missouri, researchers determined the lone star tick can transmit the heartland virus.[17] Six more cases were identified in 2012–2013 in Missouri and Tennessee.[18]

Meat allergy

The bite of the lone star tick can cause a person to develop alpha-gal meat allergy, a delayed response to nonprimate mammalian meat and meat products.[19][20] The allergy manifests as anaphylaxis — a life-threatening allergic reaction characterized by constriction of airways and a drop in blood pressure.[19] This response is triggered by an IgE antibody to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha-gal).[21] A study published in 2019 discovered alpha-gal in the saliva of the lone star tick.[22] As well as occurring in non-primate mammals, alpha-gal is also found in cat dander and in the drug cetuximab.[23][21] Allergic reactions to alpha-gal usually occur 3–6 hours after consuming red meat, unlike allergic reactions to other foods, whose onset following consumption is more or less immediate, making it more difficult to identify what caused the reaction.[19] Skin tests with standard meat test solutions are unreliable when testing for alpha-gal allergy, whereas skin tests with raw meat and/or pork kidney are more sensitive. Specific tests for determination of IgE to alpha-gal are available.[24]

See also

References

- "Amblyomma americanum" at the Encyclopedia of Life

- Fisher, Emily J.; Mo, Jun; Lucky, Anne W. (2006-04-01). "Multiple Pruritic Papules From Lone Star Tick Larvae Bites". Archives of Dermatology. 142 (4): 491–4. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.4.491. ISSN 0003-987X. PMID 16618870.

- "Geographic distribution of ticks that bite humans". cdc.gov. enters for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID), Division of Vector-Borne Diseases (DVBD). June 1, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- "lone star tick - Amblyomma americanum (Linnaeus)". entnemdept.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- "Ehrlichiosis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2018-09-25. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- "Amblyomma americanum (Lone star tick)". Wisconsin Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases. 2012-05-30. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- "CVBD - Lone Star Tick - Amblyomma americanum". www.cvbd.org. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- Soneshine, Daniel E. (1992). Biology of Ticks Volume I. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195059106.

- Resources, University of California Agriculture and Natural. "Tick Biology". entomology.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- CBC

- Holderman, Christopher J., and Phillip E. Kaufman. Lone Star Tick Amblyomma Americanum (Linnaeus): (Acari: Ixodidae). Entomology and Nematology Department, UF/IFAS Extension. The Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS), Jan. 2014. Web.

- Walker, M.D. (2017) Ticks on dogs and cats. The Veterinary Nurse, 8(9), 486-492

- Edwin J. Masters; Chelsea N. Grigery; Reid W. Masters (June 2008). "STARI, or Masters disease: lone star tick-vectored Lyme-like illness". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 22 (2): 361–376, viii. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2007.12.010. PMID 18452807.

- K. E. Ledin; N. S. Zeidner; J. M. C. Ribeiro; B. J. Biggerstaff; M. C. Dolan; G. Dietrich; L. VredEvoe; J. Piesman (March 2005). "Borreliacidal activity of saliva of the tick Amblyomma americanum". Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 19 (1): 90–95. doi:10.1111/j.0269-283X.2005.00546.x. PMID 15752182.

- Kerry L. Clark; Brian Leydet; Shirley Hartman (2013). "Lyme Borreliosis in Human Patients in Florida and Georgia, USA". Int J Med Sci. 10 (7): 915–931. doi:10.7150/ijms.6273. ISSN 1449-1907. PMC 3675506. PMID 23781138.

- Piesman J, Sinsky RJ., Ability of Ixodes scapularis, Dermacentor variabilis, and Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae) to acquire, maintain, and transmit Lyme disease spirochetes (Borrelia burgdorferi) ; J Med Entomol. 1988 September; 25(5):336-9.

- Harry M. Savage; Marvin S. Godsey Jr.; Amy Lambert; Nickolas A. Panella; Kristen L. Burkhalter; Jessica R. Harmon; R. Ryan Lash; David C. Ashley; William L. Nicholson (22 July 2013). "First Detection of Heartland Virus (Bunyaviridae: Phlebovirus) from Field Collected Arthropods". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 89 (3): 445–452. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.13-0209. PMC 3771279. PMID 23878186.

- "CDC Reports More Cases of Heartland Virus Disease". CDC. January 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "NIAID scientists link cases of unexplained anaphylaxis to red meat allergy". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 2017-11-28. Retrieved 2018-05-09.

- Commins, Scott P.; James, Hayley R.; Kelly, Libby A.; Pochan, Shawna L.; Workman, Lisa J.; Perzanowski, Matthew S.; Kocan, Katherine M.; Fahy, John V.; Nganga, Lucy W.; Ronmark, Eva; Cooper, Philip J.; Platts-Mills, Thomas A.E. (May 2011). "The relevance of tick bites to the production of IgE antibodies to the mammalian oligosaccharide galactose-α-1,3-galactose". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 127 (5): 1286–1293. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.019. PMC 3085643. PMID 21453959. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- Steinke, John W; Platts-Mills, Thomas AE; Commins, Scott P (2015). "The alpha gal story: Lessons learned from connecting the dots". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 135 (3): 589–597. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1947. ISSN 0091-6749. PMC 4600073. PMID 25747720.

- Crispell, Gary; Commins, Scott P.; Archer-Hartman, Stephanie A.; Choudhary, Shailesh; Dharmarajan, Guha; Azadi, Parastoo; Karim, Shahid (17 May 2019). "Discovery of Alpha-Gal-Containing Antigens in North American Tick Species Believed to Induce Red Meat Allergy". Frontiers in Immunology. 10: 1056. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01056. PMC 6533943. PMID 31156631.

- Gonzalez-Quintela, A.; Dam Laursen, A. S.; Vidal, C.; Skaaby, T.; Gude, F.; Linneberg, A. (August 2014). "IgE antibodies to alpha-gal in the general adult population: relationship with tick bites, atopy, and cat ownership". Clinical & Experimental Allergy. 44 (8): 1061–1068. doi:10.1111/cea.12326. ISSN 1365-2222. PMID 24750173.

- Bircher, Andreas J.; Hofmeier, Kathrin Scherer; Link, Susanne; Heijnen, Ingmar (2017-02-01). "Food allergy to the carbohydrate galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha-gal): four case reports and a review". European Journal of Dermatology. 27 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1684/ejd.2016.2908. ISSN 1952-4013. PMID 27873733.

External links

Data related to Amblyomma americanum at Wikispecies

Data related to Amblyomma americanum at Wikispecies Media related to Amblyomma americanum at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Amblyomma americanum at Wikimedia Commons- Kansas State University - Animal Parasitology - Hypostomes (and dentition) of three tick species