Aldfrith of Northumbria

Aldfrith (Early Modern Irish: Flann Fína mac Ossu; Latin: Aldfrid, Aldfridus; died 14 December 704 or 705) was king of Northumbria from 685 until his death. He is described by early writers such as Bede, Alcuin and Stephen of Ripon as a man of great learning. Some of his works and some letters written to him survive. His reign was relatively peaceful, marred only by disputes with Bishop Wilfrid, a major figure in the early Northumbrian church.

| Aldfrith | |

|---|---|

The lion symbol used on Aldfrith's coinage[1] | |

| King of Northumbria | |

| Reign | 685–704/705 |

| Predecessor | Ecgfrith |

| Successor | Disputed between Osred and Eadwulf |

| Died | 14 December 704/705 Driffield, East Riding of Yorkshire |

| Consort | Cuthburh |

| Issue | Osred Osric? Offa Osana? |

| Father | Oswiu |

| Mother | Fín |

Aldfrith was born on an uncertain date to Oswiu of Northumbria and an Irish princess named Fín. Oswiu later became King of Northumbria; he died in 670 and was succeeded by his son Ecgfrith. Aldfrith was educated for a career in the church and became a scholar. However, in 685, when Ecgfrith was killed at the battle of Nechtansmere, Aldfrith was recalled to Northumbria, reportedly from the Hebridean island of Iona, and became king.

In his early-8th-century account of Aldfrith's reign, Bede states that he "ably restored the shattered fortunes of the kingdom, though within smaller boundaries".[2] His reign saw the creation of works of Hiberno-Saxon art such as the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Codex Amiatinus, and is often seen as the start of Northumbria's golden age.

Background and accession

By the year 600, most of what is now England had been conquered by invaders from the continent, including Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. Bernicia and Deira, the two Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the north of England, were first united under a single ruler in about 605 when Æthelfrith, king of Bernicia, extended his rule over Deira. Over the course of the 7th century, the two kingdoms were sometimes ruled by a single king, and sometimes separately. The combined kingdom became known as the kingdom of Northumbria: it stretched from the River Humber in the south to the River Forth in the north.[3]

In 616, Æthelfrith was succeeded by Edwin of Northumbria, a Deiran. Edwin banished Æthelfrith's sons, including both Oswald and Oswiu of Northumbria. Both spent their exile in Dál Riata, a kingdom spanning parts of northeastern Ireland and western Scotland. Oswiu was a child when he came to Dál Riata, and grew up in an Irish milieu.[4] He became a fluent speaker of Old Irish,[5] and may have married a princess of the Uí Néill dynasty, probably Fín the daughter (or possibly granddaughter) of Colmán Rímid.[6] Aldfrith was a child of this marriage, but his date of birth is unrecorded.[7] He was probably thus a cousin or nephew of the noted scholar Cenn Fáelad mac Aillila, and perhaps a nephew of Bishop Finan of Lindisfarne.[8] Irish law made Fín's kin, the Cenél nEógain of the northern Uí Néill, responsible for his upbringing.[9] The relationship between Aldfrith's father and mother was not considered a lawful marriage by Northumbrian churchmen of his day, and he is described as the son of a concubine in early sources.[10]

Oswald and Oswiu returned to Northumbria after Edwin's death in 633, and between them they ruled for much of the middle of the 7th century. The 8th-century monk and chronicler Bede lists both Oswald and Oswiu as having held imperium, or overlordship, over the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms; in Oswiu's case his dominance extended beyond the Anglo-Saxons to the Picts, the Gaels of Dál Riata, and the many obscure and nameless native British kingdoms in what are now North West England and southern Scotland.[11] Oswiu's overlordship was ended in 658 by the rise of Wulfhere of Mercia, but his reign continued until his death in 670, when Ecgfrith, one of his sons by his second wife, Eanflæd, succeeded him. Ecgfrith was unable to recover Oswiu's position in Mercia and the southern kingdoms, and was defeated by Wulfhere's brother Æthelred in a battle on the River Trent in 679.[12]

Ecgfrith sent an army under his general, Berht, to Ireland in 684 where he ravaged the plain of Brega, destroying churches and taking hostages. The raid may have been intended to discourage support for any claim Aldfrith might have to the throne, though other motives are possible.[13]

Ecgfrith's two marriages—the first to the saintly virgin Æthelthryth (Saint Audrey), the second to Eormenburh—produced no children.[15] He had two full brothers: Alhfrith, who is not mentioned after 664, and Ælfwine, who was killed at the battle on the Trent in 679.[16] Hence the succession in Northumbria was unclear for some years before Ecgfrith's death. Bede's Life of Cuthbert recounts a conversation between Cuthbert and Abbess Ælfflæd of Whitby, daughter of Oswiu, in which Cuthbert foresaw Ecgfrith's death. When Ælfflæd asked about his successor, she was told she would love him as a brother:

"But," said she, "I beseech you to tell me where he may be found." He answered, "You behold this great and spacious sea, how it aboundeth in islands. It is easy for God out of some of these to provide a person to reign over England." She therefore understood him to speak of [Aldfrith], who was said to be the son of her father, and was then, on account of his love of literature, exiled to the Scottish islands.[17]

Cuthbert, later considered a saint, was a second cousin of Aldfrith (according to Irish genealogies), which may have been the reason for his proposal as monarch.[18][19]

Ecgfrith was killed during a campaign against his cousin, the King of the Picts Bridei map Beli, at a battle known as Nechtansmere to the Northumbrians, in Pictish territory north of the Firth of Forth.[20] Bede recounts that Queen Eormenburh and Cuthbert were visiting Carlisle that day, and that Cuthbert had a premonition of the defeat.[21] Ecgfrith's death threatened to break the hold of the descendants of Æthelfrith on Northumbria, but the scholar Aldfrith became king and the thrones of Bernicia and Deira remained united.[22]

Although rival claimants of royal descent must have existed, there is no recorded resistance to Aldfrith's accession.[23] It has also been suggested that Aldfrith's ascent was eased by support from Dál Riata, the Uí Néill, and the Picts, all of whom might have preferred the mature, known quantity of Aldfrith to an unknown and more warlike monarch, such as Ecgfrith or Oswiu had been.[24] The historian Herman Moisl, for example, wrote that "Aldfrith was in Iona in the year preceding the battle [of Nechtansmere]; immediately afterwards, he was king of Northumbria. It is quite obvious that he must have been installed by the Pictish-Dál Riatan alliance".[25] Subsequently, a battle between the Northumbrians and the Picts in which Berht was killed is recorded by Bede and the Irish annals in 697 or 698.[26] Overall, Aldfrith appears to have abandoned his predecessors' attempts to dominate Northumbria's neighbours.[27]

Aldfrith's Northumbria

Bede, paraphrasing Virgil, wrote that following Ecgfrith's death, "the hopes and strengths of the English realm began 'to waver and slip backward ever lower'".[2] The Northumbrians never regained the dominance of central Britain lost in 679, or of northern Britain lost in 685. Nonetheless, Northumbria remained one of the most powerful states of Britain and Ireland well into the Viking Age.[28]

Aldfrith ruled both Bernicia and Deira throughout his reign, but the two parts remained distinct, and would again be divided by the Vikings in the late 9th century.[29] The centre of Bernicia lay in the region around the later Anglo-Scottish border, with Lindisfarne, Hexham, Bamburgh, and Yeavering being important religious and royal centres. Even after Ecgfrith's death, Bernicia included much of modern southeast Scotland, with a presumed royal centre at Dunbar, and religious centres at Coldingham and Melrose.[30] The details of the early Middle Ages in northwest England and southwest Scotland are more obscure, but a Bishop of Whithorn is known from shortly after Aldfrith's reign. York, Catterick, Ripon, and Whitby appear to have been important sites in Deira.[31]

Northumbria's southern frontier with Mercia ran across England, from the Humber in the east, following the River Ouse and the River Don, to the Mersey in the west. Some archaeological evidence, the Roman Rig dyke, near modern Sheffield, appears to show that it was a defended border, with large earthworks set back from the frontier.[32] The Nico Ditch, to the south of modern Manchester, has been cited in this context, though it has also been argued that it was simply a boundary marker without fortifications.[32][33] In the far north, the evidence is less clear, and it appears that authority lay with sub-kings, perhaps including native British rulers.[32] The family of Ecgfrith's general Berht may have been one such dynasty of under-kings.[34]

Relations with the Church

Along with the king, royal family, and chief noblemen, the church was a major force in Northumbria. Churchmen were not only figures of spiritual authority, they were major landowners, who also controlled trade, centred at major churches and monasteries in a land without cities and towns. The bishopric of Lindisfarne was held by Cuthbert at Aldfrith's accession; Cuthbert was succeeded by the Irish-educated Eadberht, who would later be Abbot of Iona and bring the Easter controversy to an end, and then by Eadfrith, creator of the Lindisfarne Gospels. The bishops of Lindisfarne sometimes held the see of Hexham, but during Aldfrith's reign it was held by John of Beverley, a pupil and protégé of Theodore, the Archbishop of Canterbury. The bishopric of York was held by Bosa in 685. Wilfrid was given the see in 687, but removed in 691 with Bosa returning to York. The short-lived see at Abercorn, created in 681 for Bishop Trumwine, collapsed in the period after Ecgfrith's death and the first known Bishop of Whithorn was appointed in the reign of King Ceolwulf. Important monasteries existed at Whitby, where the known abbesses tended to be members of the Deiran royal family, at Monkwearmouth-Jarrow, where Bede was a monk, and at Ripon.[35]

Aldfrith appears to have had the support of leading ecclesiastics, most notably his half-sister Ælfflæd and the highly respected Bishop Cuthbert.[36] He is known to have received confirmation at the hands of Aldhelm, later the Bishop of Sherborne in the south-western Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Wessex. Aldhelm too had received an Irish education, but in Britain, at Malmesbury. Correspondence between the two survives, and Aldhelm sent Aldfrith his treatise on the numerology of the number seven, the Epistola ad Acircium.[37] Aldfrith also owned a manuscript on cosmography, which (according to Bede) he purchased from Abbot Ceolfrith of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow in exchange for an estate valued at eight hides.[38] Aldfrith was a close friend of Adomnán, Abbot of Iona from 679, and may have studied with him.[39] In the 680s Aldfrith twice met with Adomnán, who came to seek the release of the Irish captives taken in Berht's expedition of 684. These were released and Adomnán presented Aldfrith with a copy of his treatise De Locis Sanctis ("On the Holy Places"), a description of the places of pilgrimage in the Holy Land, and at Alexandria and Constantinople. Bede reports that Aldfrith circulated Adomnán's work for others to read.[40]

Bede described Aldfrith as a scholar, and his interest in learning distinguishes him from the earlier Anglo-Saxon warrior kings, such as Penda. Irish sources describe him as a sapiens, a term from the Latin for wise that refers to a scholar not usually associated with a particular church. It implies a degree of learning and wisdom that led historian Peter Hunter Blair to compare Aldfrith to the Platonic ideal of the philosopher king.[41] Bede also makes it clear that the church in Aldfrith's day was less subject to lay control of monasteries, a practice he dated from the time of Aldfrith's death.[42]

Aldfrith's relations with the Church were, however, not always smooth. He inherited from Ecgfrith a troubled relationship with Wilfrid, a major ecclesiastical figure of the time. Wilfrid, the bishop of York, had been exiled by Ecgfrith for his role in persuading Ecgfrith's wife, Æthelthryth, to remain a saintly celibate. In 686, at the urging of Archbishop Theodore, Aldfrith allowed Wilfrid to return.[43][44] Aldfrith's relations with Wilfrid were stormy; the hostility between the two was partly caused by Aldfrith's allegiances with the Celtic Church, a consequence of his upbringing in exile.[45] A more significant cause of strife was Wilfrid's opposition to Theodore's division, in 677, of his huge Northumbrian diocese. When Wilfrid returned from exile the reconciliation with Aldfrith did not include Aldfrith's support for Wilfrid's attempts to recover his episcopal authority over the whole of the north.[46] By 691 or 692 their differences were beyond repair. Wilfrid's hagiographer writes:[47]

For a while all would be peace between the wise King Aldfrith and our holy bishop, and a happier state of affairs could hardly be imagined. Then spite would boil up again and the situation would be reversed. And so they continued for years, in and out of friendship with each other, till finally their quarrels came to a head and the king banished Wilfrid from Northumbria.

Wilfrid spent his exile in Mercia, where he enjoyed the staunch support of King Æthelred. In 702 or 703, Aldfrith convened a council at Austerfield, on the southern border of Northumbria, which was attended by Berhtwald, Archbishop of Canterbury, and many bishops. The question of Wilfrid's return to Northumbria was hotly debated and then rejected by the bishops. According to Stephen of Ripon, King Aldfrith offered to use his army to pressure Wilfrid into accepting the decision, but the bishops reminded him that he had promised Wilfrid safe-conduct.[48] After returning to Mercia, Wilfrid was excommunicated by his enemies among the bishops. He responded by journeying to Rome, where he appealed in person to Pope John VI. The Pope provided him with letters to Aldfrith ordering that Wilfrid be restored to his offices.[49] Aldfrith refused to receive the letters, and Wilfrid remained in disfavour.[50]

Northumbria's Golden Age

Aldfrith's reign is considered the beginning of Northumbria's Golden Age, which lasted until the end of the 8th century. The period saw the flowering of Insular art in Northumbria and produced the Lindisfarne Gospels, perhaps begun in Aldfrith's time, the scholarship of Bede, and the beginnings of the Anglo-Saxon missions to the continent.[51]

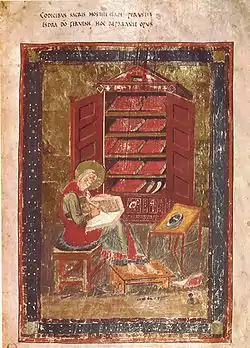

The Lindisfarne Gospels are believed to be the work of Eadfrith of Lindisfarne, bishop of Lindisfarne from 698. They are not the only surviving Northumbrian illuminated manuscripts from Aldfrith's time. Also active at Lindisfarne in the late 7th century was the scribe known as the "Durham-Echternach calligrapher", who produced the Durham Gospels and the Echternach Gospels.[52] The Codex Amiatinus was a product of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow, made on the orders of Abbot Ceolfrid, probably in the decade after Aldfrith's death.[53]

Two significant items of jewellery from Northumbria in this period have survived. The Ripon Jewel, discovered in the precincts of Ripon Cathedral in 1977, is difficult to date but its grandeur and the location of the find have suggested a link with Bishop Wilfrid, whose rich furnishings of the church at Ripon are on record.[54] Bishop Cuthbert's pectoral cross was buried with him during Aldfrith's reign, either at his death in 687 or his reburial in 698 and is now at Durham Cathedral.[55] There are few surviving architectural or monumental remains from the period. The Bewcastle Cross, the Ruthwell Cross and the Hexham Cross are probably to be dated to one or two generations after Aldfrith's time.[56] Escomb Church is the best preserved Northumbrian church of the period, dated to the late 7th century. The ruined chapel at Heysham, overlooking Morecambe Bay, may be somewhat later in date.[57]

The Northumbrian coinage is thought to have begun during Aldfrith's reign. Early silver coins, known as sceattas, appeared, replacing the impractical gold thrymsa as a medium of exchange.[58] Exceptionally for the period, Aldfrith's coins bear his name, rather than that of a moneyer, in an Irish uncial script. Most show a lion, with upraised tail.[59]

Heirs, death, and succession

Aldfrith was married to Cuthburh, sister of King Ine of Wessex; the marriage thus allied Aldfrith with one of the most powerful kings in Anglo-Saxon England. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that Aldfrith and Cuthburh separated, and Cuthburh established an abbey at Wimborne Minster where she was abbess. At least two sons were born to Aldfrith, but whether Cuthburh was their mother is unrecorded.[60] Osred, born around 696 or 697, succeeded to the throne after a civil war following Aldfrith's death. Little is known of Offa, who is presumed to have been killed after being taken from Lindisfarne in 750 on the orders of King Eadberht of Northumbria.[61] Osric, who was later king, may have been Aldfrith's son, or alternatively the son of Aldfrith's half-brother Alhfrith.[62] The 13th-century discovery of a tomb thought to be that of St Osana has led to the suggestion that Osana was the daughter of Aldfrith, although this view is not widely held by modern historians.[63]

Aldfrith was said to have been ill for some time before his death, dying on 14 December 704 or 705.[64] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle adds that he died at Driffield in the East Riding of Yorkshire. The succession was disputed by Eadwulf, supported initially by Bishop Wilfrid, and supporters of Aldfrith's young son Osred, apparently led by Berht's kinsman Berhtfrith.[65]

The reports of Aldfrith's death in the Irish annals call him Aldfrith son of Oswiu, but some of these are glossed by later scribes with the name Flann Fína mac Ossu. A collection of wisdom literature attributed to Flann Fína, the Briathra Flainn Fhina Maic Ossu, has survived, though the text is not contemporary with Aldfrith as it is in Middle Irish, a form of Irish not in use until the 10th century.[66]

Learning merits respect.

Intelligence overcomes fury.

Truth should be supported.

Falsehood should be rebuked.

Iniquity should be corrected.

A quarrel merits mediation.

Stinginess should be spurned.

Arrogance deserves oblivion.Good should be exalted.

Notes

- For the identification as a lion, see Gannon, pp. 125–127.

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book IV, Chapter 26.

- Hunter Blair, An Introduction, pp. 42–45.

- Philip Holdsworth, "Oswiu", in Lapidge et al., Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 349.

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book III, Chapter 25.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 143.

- Grimmer, §25; Kirby, p. 143.; Williams, p. 18.

- Colmán Rímid mac Báetáin died circa 604, and is listed as a High King of Ireland, see Charles-Edwards, pp. 502 & 504; for Fín as granddaughter of Colmán Rímid see Kirby, p. 143 and Cramp; for the possible relationship with Bishop Fínan, see Campbell, p. 86.

- Grimmer, §23.

- The term used is nothus, bastard. Some later sources doubt his paternity, but well-informed contemporary ones, including those derived from the Chronicle of Ireland are in no doubt that he was Oswiu's son, for example, the notice of his death in the Annals of Ulster, s.a. 704, which calls him "Aldfrith m. Ossu". See also Yorke, Conversion, pp. 226–227.

- Holdsworth; Kirby, pp 95–98.

- Fraser, pp. 119–120, and Kirby, pp. 84–85, suggest that the defeat at the Trent was a greater blow to Northumbrian pretensions to the overlordship of Britain than the defeat at Nechtansmere in 685.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 85, makes this suggestion. Charles-Edwards, chapter 10, and especially pp. 429–438, suggests that ecclesiastical politics may have been of great importance. See also Fraser, pp. 43–47.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 76.

- Alan Thacker, "Ecgfrith", ODNB; Cramp, "Aldfrith", ODNB.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, pp. 96, 103.

- Bede, Life of Cuthbert, chapter XXIV. D.P. Kirby suggests that "[r]ather than asking Cuthbert ingenuously who would succeed Ecgfrith, [Ælfflæd] was probably testing his loyalties"; Kirby, p. 106. The anonymous Life of Cuthbert, written during Aldfrith's reign, is generally similar in its account, but differs in the last sentence, which reads "Then she quickly remembered that he spoke of Aldfrith who now reigns in peace, who was then on the island they call [Iona]"; Fraser, pp. 138–139.

- 'Was St.Cuthbert an Irishman'

- Archived 24 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Aldfrith of Northumbria and the Irish genealogies. Ireland, C. A., in Celtica 22 (1991)].

- Dunnichen in Angus has, until recently, been the preferred site; see e.g. Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 99. An alternative site at Dunachton in Badenoch has been proposed by Woolf, Dun Nechtain, Fortriu and the Geography of the Picts

- Bede, Life of Cuthbert, chapter XXVII.

- Kirby, p. 106, notes "Aelfflaed's question to Cuthbert reveals the ambition of this family, which had possessed royal power continuously since 633 or 634, to hold on to it". The succession at Aldfrith's death was disputed, and a distant branches of his own as well as other families contested successfully for power after the death of Aldfrith's son Osred.

- D.P. Kirby notes "[t]he prestige of Oswiu's family, or else its capacity for intimidation, must have been very considerable for Aldfrith to return and rule in what seems to have been domestic peace"; Kirby, p. 144.

- Kirby, p. 144. Cramp suggests that Aldfrith may already have been present in Northumbria at Ecgfrith's death; Blair, Northumbria, p. 52, prefers Iona.

- Moisl, "Bernician Royal Dynasty", p. 121.

- Kirby, p. 142; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 697; Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book V, Chapter 24.

- Cramp, "Aldfrith", ODNB.

- Campbell, pp. 88ff; Kirby, pp. 142–143.

- Holdsworth, "Northumbria".

- Alcock, Kings and Warriors, pp. 214–7, for discussion of Dunbar as a Bernician royal centre.

- Blair, Introduction, pp 37–49, p. 42, map 7, & p. 145, map 9; Higham, cc. 4–5, passim.

- Higham, pp. 140–144.

- Nevell, Lands and Lordships, p. 41.

- Kirby, p. 100; Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, pp. 92 & 171.

- Blair, Introduction, pp. 132–141.

- Yorke, Conversion, pp 226–227.

- Lapidge, "Aldfrith"; Lapidge, "Aldhelm"; Blair, Northumbria, p. 53; Mayr-Harting, p. 195.

- Blair, World of Bede, pp. 184–185; Bede, Life of the Abbots of Wearmouth and Jarrow, c. 15.

- Grimmer, §25, note 60.

- Blair, World of Bede, pp. 185–186; Yorke, Conversion, pp. 17–18; Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book V, Chapters 15–17.

- The use of the term sapiens is discussed by Charles-Edwards, pp. 264–271. Blair, Northumbria, p. 53–54, writes of Aldfrith as "a man perhaps not so very far removed from the Platonic ideal of the Philosopher king" and as "one of Northumbria's first and greatest scholars".

- Bede, "Letter to Egbert", in Sherley-Price, Bede, p. 346.

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book V, Chapter 19.

- Life of Wilfrid, Chapters 43–44.

- Blair, Introduction, p. 137.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 143.

- Stephen of Ripon, Life of Wilfrid, Chapter 45.

- Stephen of Ripon, Life of Wilfrid, Chapters 46–48.

- Stephen of Ripon, Life of Wilfrid, Chapters 49–55.

- Life of Wilfrid, Chapters 58–59; Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book V, Chapter 19.

- Art and scholarship, see Higham, pp. 155–166; Blair, Introduction, pp. 311–329; missions, see Blair, Introduction, pp. 162–164.

- The Northumbrian origins of the Echternach Gospels have been debated, with some historians arguing for an Irish origin, see Brown, "Echternach Gospels"; Higham, Kingdom of Northumbria, pp. 155–160; Verey, "Lindisfarne of Rath Maelsigi?". The Lichfield Gospels are sometimes linked to Northumbria although this is far from certain; Higham, Kingdom of Northumbria, p. 158.

- Nees, Early Medieval Art, pp. 164–167 at 165; Alcock, Kings and Warriors, pp. 353–354.

- Hall et al., "The Ripon Jewel".

- Higham, Kingdom of Northumbria, p. 159.

- Ó Carragáin, "The Necessary Distance", p. 192, argues that the Agnus Dei imagery on both monuments places them in an 8th-century context; likewise Ó Carragáin, "Ruthwell Cross", proposes a date between 730 and 750 for Ruthwell; Bailey, "Bewcastle", estimates between 725 and 750 for Bewcastle; more generally see Alcock, Kings and warriors, pp. 377–382.

- Blair, "Escomb"; Alcock, Kings and warriors, pp. 273–285.

- Kirby, p. 146. Higham, pp. 166–168, gives an overview of Northumbrian coinage.

- Gannon, pp. 125–126.

- Kirby, p. 145.

- Kirby, pp. 143–150; Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, pp. 89–90 & 93.

- Kirby, p. 147; Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, pp. 88 & 90.

- Coulstock, Collegiate Church, p. 31.

- For the year of Aldfrith's death see Kirby, p. 145: the Irish annals record his death under the year 703, which is 704 A.D., while Bede gives 705 and a reign of nineteen years.

- Life of Wilfrid, Chapters 59–60; Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book V, Chapter 19.

- Ireland, pp. 70–75.

References

- —. The Annals of Ulster, volume 1. CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- Alcock, Leslie. Kings and warriors, craftsmen and priests in Northern Britain AD 550–850. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 2003. ISBN 0-903903-24-5.

- Bailey, Richard N., "Bewcastle". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Ed. Michael Lapidge. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Blair, Peter Hunter. An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977. ISBN 0-521-29219-0.

- Blair, Peter Hunter. Northumbria in the Days of Bede. London: Victor Gollancz, 1976. ISBN 0-575-01840-2.

- Blair, Peter Hunter. The World of Bede. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-521-39138-5.

- Brown, Michelle P. "Echternach Gospels". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Ed. Michael Lapidge. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Brown, Michelle P. "Lindisfarne Gospels". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Ed. Michael Lapidge. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Campbell, James. "Elements in the Background to the Life of Saint Cuthbert and his early cult". The Anglo-Saxon State. London: Hambledon, 2000. ISBN 1-85285-176-7.

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. Early Christian Ireland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-521-36395-0.

- Coulstock, Patricia H. Studies in the History of Medieval Religion 5: The Collegiate Church of Wimborne Minster. Boydell & Brewer, 1993. ISBN 0-85115-339-9.

- Cramp, Rosemary. "Aldfrith (d. 704/705)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

- Farmer, D. H. and J. H. Webb. The Age of Bede. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983. ISBN 0-14-044727-X.

- Fraser, James. The Pictish Conquest: The Battle of Dunnichen 685 & the birth of Scotland. Stroud: Tempus, 2006. ISBN 0-7524-3962-6.

- Gannon, Anna. The Iconography of Early Anglo-Saxon Coinage: Sixth to Eighth Centuries. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-19-925465-6.

- Grimmer, Martin. "The Exogamous Marriages of Oswiu of Northumbria". The Heroic Age 9 (2006). Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- Hall, R. A. & E. Paterson, & C. Mortimer, with Niamh Whitfield. "The Ripon Jewel". Northumbria's Golden Age. Eds Janes Hawkes & Susan Mills. Stroud: Sutton, 1999. ISBN 0-7509-1685-0

- Higham, N. J. The Kingdom of Northumbria AD 350–1100. Stroud: Sutton, 1993. ISBN 0-86299-730-5.

- Holdsworth, Philip. "Northumbria". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Ed. Michael Lapidge. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Holdsworth, Philip. "Oswiu". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Ed. Michael Lapidge. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Ireland, C. A. Archived 24 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Aldfrith of Northumbria and the Irish genealogies. Celtica 22 (1991)

- Ireland, C. A. Old Irish wisdom attributed to Aldfrith of Northumbria: An edition of Briathra Flainn Fhina maic Ossu. Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 1999. ISBN 0-86698-247-7.

- Kirby, D. P. The Earliest English Kings. London: Unwin Hyman, 1991. ISBN 0-04-445691-3.

- Lapidge, Michael. "Aldfrith". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Ed. Michael Lapidge. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Lapidge, Michael. "Aldhelm". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Ed. Michael Lapidge. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry. The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. London: Batsford, 1972. ISBN 0-7134-1360-3.

- Moisl, Herman. "The Bernician Royal Dynasty and the Irish in the Seventh Century". Peritia: The Journal of the Medieval Academy of Ireland 2 (1983): 103–26.

- Nees, Lawrence. Early Medieval Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-19-284243-9.

- Nevell, Mike (1998). Lands and Lordships in Tameside. Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council with the University of Manchester Archaeological Unit. ISBN 1-871324-18-1.

- Ó Carragáin, Éamonn. "Ruthwell Cross". The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Ed. Michael Lapidge. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Ó Carragáin, Éamonn. "The Necessary Distance: Imitatio Romae and the Ruthwell Cross". Northumbria's Golden Age. Eds Janes Hawkes & Susan Mills. Stroud: Sutton, 1999. ISBN 0-7509-1685-0

- Rollason, D. W. "Why was St Cuthbert so popular?" Cuthbert: Saint and Patron. Ed. D. W. Rollason. Durham: The Dean and Chapter of Durham Cathedral, 1987. ISBN 0-907078-24-9.

- Sherley-Price, Leo, R. E. Latham, and D. H. Farme. Bede: Ecclesiastical History of the English People, with Bede's letter to Egbert and Cuthbert's letter on the death of Bede. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1990. ISBN 0-14-044565-X.

- Stenton, Frank. Anglo-Saxon England. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971. ISBN 0-19-280139-2.

- Verey, Christopher D. "Lindisfarne or Rath Maelsigi? The Evidence of the Texts". Northumbria's Golden Age. Eds Janes Hawkes & Susan Mills. Stroud: Sutton, 1999. ISBN 0-7509-1685-0

- Williams, Ann. Kingship and Government in Pre-Conquest England, c. 500–1066. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1999. ISBN 0-333-56798-6.

- Woolf, Alex. Dun Nechtain, Fortriu and the Geography of the Picts The Scottish Historical Review 85, 182–201, 2006.

- Yorke, Barbara. Kings and Kingdoms in Early Anglo-Saxon England. London: Seaby, 1990. ISBN 1-85264-027-8.

- Yorke, Barbara. The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c. 600–800. London: Longman, 2006. ISBN 0-582-77292-3.

- Ziegler, Michelle. "Oswald and the Irish". The Heroic Age 4 (2001). Retrieved 28 January 2013.