Alachua County, Florida

Alachua County (/əˈlætʃuə/ (![]() listen) ə-LATCH-oo-ə) is a county located in the north central portion of the U.S. state of Florida. As of the 2010 census, the population was 247,336.[1] The county seat is Gainesville,[2] the home of the University of Florida since 1906, when the campus opened with 106 students.

listen) ə-LATCH-oo-ə) is a county located in the north central portion of the U.S. state of Florida. As of the 2010 census, the population was 247,336.[1] The county seat is Gainesville,[2] the home of the University of Florida since 1906, when the campus opened with 106 students.

Alachua County | |

|---|---|

Alachua County Courthouse | |

Flag  Logo | |

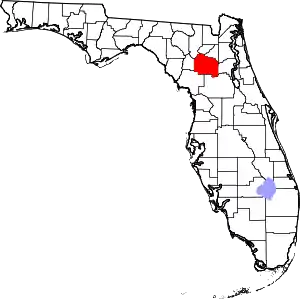

Location within the U.S. state of Florida | |

Florida's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 29°41′N 82°22′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | February 29, 1824 |

| Named for | Alachua (Timucuan word for "sinkhole") |

| Seat | Gainesville |

| Largest city | Gainesville |

| Area | |

| • Total | 969 sq mi (2,510 km2) |

| • Land | 875 sq mi (2,270 km2) |

| • Water | 94 sq mi (240 km2) 9.7%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2019) | 269,043 |

| • Density | 301/sq mi (116/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 3rd |

| Website | www |

Alachua County is included in the Gainesville Metropolitan Statistical Area. The county is known for its diverse culture, local music, and artisans. Much of its economy revolves around the university, which had nearly 55,000 students in fall 2016.

History

Early history

The first people known to have entered the area of Alachua County were Paleo-Indians, who left artifacts in the Santa Fe River basin prior to 8000 BCE. Artifacts from the Archaic period (8000 - 2000 BCE) have been found at several sites in Alachua County. Permanent settlements appeared in what is now Alachua County around 100 CE, as people of the wide-ranging Deptford culture developed the local Cades Pond culture. The Cades Pond culture gave way to the Alachua culture around 600 CE.[3]

The Timucua-speaking Potano tribe lived in the Alachua culture area in the 16th century, when the Spanish entered Florida. The Potano were incorporated by the colonists in the Spanish mission system, but new infectious diseases, rebellion, and raids by tribes backed by the English led to severe population declines. What is now Alachua County had lost much of its indigenous population by the early 18th century.[4]

In the 17th century Francisco Menéndez Márquez, Royal Treasurer for Spanish Florida, established the La Chua ranch on the northern side of what is now known as Payne's Prairie, on a bluff overlooking the Alachua Sink.[5] Chua may have been the Timucua language word for sinkhole. Lieutenant Diego Peña reported in 1716 that he passed by springs named Aquilachua, Usichua, Usiparachua, and Afanochua while traveling through what is now Suwannee County. In the twentieth-century, anthropologist J. Clarence Simpson assumed that the named springs were in fact sinkholes.[6] The Spanish later called the interior of Florida west of the St. Johns River Tierras de la Chua, which became "Alachua Country" in English.[7]

Around 1740 a band of Oconee people led by Ahaya, who was called "Cowkeeper" by the English, settled on what is now Payne's Prairie.[8] Ahaya's band became known as the Alachua Seminole. In 1774 botanist William Bartram visited Ahaya's town, Cuscowilla, near what Bartram called the Alachua Savanna. King Payne, who succeeded Ahaya as chief of the Alachua Seminole, established a new town known as Payne's Town.

In 1812, during the Patriot War of East Florida, an attempt by American adventurers to seize Spanish Florida, a force of more than 100 volunteers from Georgia led by Colonel Daniel Newnan ran into a band of Alachua Seminole led by King Payne near Newnans Lake. After several days of intermittent fighting, Colonel Newnan's force withdrew. King Payne was wounded in the fight and died two months later. The Alachua Seminole left Payne's Town and moved further west and south, but other bands of Seminole moved in. A second American expedition in 1813 of U. S. Army troops and militia from Tennessee, led by Lt. Colonel Thomas Adams Smith, found some Seminoles, killing about 20, and burned every Seminole village they could find in the area.[9][10]

In 1814 a group of more than 100 American settlers moved to a point believed to be near the abandoned Payne's Town (near present-day Micanopy) and declared the establishment of the District of Elotchaway of the Republic of East Florida. The settlement collapsed a few months later after its leader, Colonel Buckner Harris, was killed by Seminole; the settlers returned to Georgia.[11]

American settlement

In 1817 F. M. Arredondo received the 20-mile square Arredondo Grant in the southern part of what is Alachua County. By the time Florida was formally transferred from Spain to the United States, people from the United States and from Europe were settling in the area. Wanton's Store, near the site of the abandoned King Payne's Town, attracted settlers, primarily from Europe, who founded Micanopy. The 1823 Treaty of Moultrie Creek required the Seminole to move a reservation south of what is now Ocala, and the flow of settlers into the area increased. Many occupied former Seminole towns, such as Hogtown.

Alachua County was created by the Florida territorial legislature in 1824. The new county stretched from the border with Georgia south to Charlotte Harbor. The original county seat was Wanton's (the name Micanopy had not been adopted, yet). In 1828 the county seat was moved to Newnansville, located near the current site of the city of Alachua.[11]

As population increased in the area, Alachua County was soon reduced in size to organize new counties. In 1832 the county's northern part, including Newnansville was separated to create Columbia County, forcing the county seat to be moved to various temporary locations. In 1834 Hillsborough County was created, which included the area around Tampa Bay down to Charlotte Harbor. In 1839 that part of Columbia County south of the Santa Fe River was returned to Alachua County, and Newnansville was restored as the county seat. Hernando County was created in 1843 from that part of Alachua County south of the Withlacoochee River; Marion County was created in 1844; and Levy County was created in 1846 from that part of Alachua County west of the Suwannee River. It would be another 80 years before Alachua County was again reduced in size.[11]

In 1854, the new railroad from Fernandina to Cedar Key bypassed Newnansville, and Gainesville, a new town on the railroad, began to draw business and residents away from Newnansville. Gainesville was designated that year as the new county seat.[12]

Lynchings and disenfranchisement

During the post-Reconstruction period, white Democrats regained control of the state legislature and worked to restore white supremacy. Violence against blacks, including lynchings, rose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as whites imposed Jim Crow and discriminatory laws, disenfranchising most blacks, which forced them out of the political system. Alachua County was the site of 21 documented lynchings between 1891 and 1926.[13] The first three documented lynchings, in Gainesville in 1891, involved two black men and a white man, who were associated with the notorious Harmon Murray.[14] Ten lynchings took place in Newberry, six of them in a mass lynching there in 1916.[13] These lynchings were conducted outside the justice system, by mobs or small groups working alone. Nineteen of the victims were black; two were white.[15] (A 2015 report by the Equal Justice Institute, based in Montgomery, Alabama, had identified 18 lynchings.[16] The Historical Commission documented three more, including two white men.)[15]

In September 2017, the County Commission approved plans to place markers with the names of the victims in the county. (See linked article for names of these individuals.)[15] They are working with the Historical Commission and cities to discuss how best to achieve this.[13] A state historical marker on the Newberry Lynchings was dedicated in 2019.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 969 square miles (2,510 km2), of which 875 square miles (2,270 km2) is land and 94 square miles (240 km2) (9.7%) is water.[17]

Adjacent counties

- Bradford County - north

- Union County - north

- Clay County, Florida - northeast

- Putnam County - east

- Marion County - southeast

- Levy County - southwest

- Gilchrist County - west

- Columbia County - northwest

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1830 | 2,204 | — | |

| 1840 | 2,282 | 3.5% | |

| 1850 | 2,524 | 10.6% | |

| 1860 | 8,232 | 226.1% | |

| 1870 | 17,328 | 110.5% | |

| 1880 | 16,462 | −5.0% | |

| 1890 | 22,934 | 39.3% | |

| 1900 | 32,245 | 40.6% | |

| 1910 | 34,305 | 6.4% | |

| 1920 | 31,689 | −7.6% | |

| 1930 | 34,365 | 8.4% | |

| 1940 | 38,607 | 12.3% | |

| 1950 | 57,026 | 47.7% | |

| 1960 | 74,074 | 29.9% | |

| 1970 | 104,764 | 41.4% | |

| 1980 | 151,348 | 44.5% | |

| 1990 | 181,596 | 20.0% | |

| 2000 | 217,955 | 20.0% | |

| 2010 | 247,336 | 13.5% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 269,043 | [18] | 8.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[19] 1790-1960[20] 1900-1990[21] 1990-2000[22] 2010-2015[1] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census,[23] there were 247,336 people, 100,516 households, and 53,500 families residing in the county. There were 112,766 housing units in the county, an occupancy rate of 89.1%; of the occupied units, 54,768 (54.5%) were owner-occupied and 45,748 (45.5%) were renter-occupied. The population density was 282.91/sq mi (109.24/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 172,156 (69.9%) White, 50,282 (20.3%) Black or African American, 906 (0.3%) Native American, 13,235 (5.4%) Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 1.7% from other races, and 2.6% from two or more races. 20,752 (8.4%) of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

Of the 100,516 households, 22.0% included children under the age of 18, 36.4% included a married husband and wife couple, 4.0% had a male head of house with no wife present, 12.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 46.8% were non-families. 24.8% of all households included at least one child under the age of 18, and 19.6% included at least one member 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.32 and the average family size was 2.91.

The demographic spread showed 17.9% under the age of 18 and 10.8% who were 65 years of age or older; 48.4% of the population identified as male and 51.6% as female. The median age was 30.1 years.

The five year American Community Survey completed 2011 gave a median household income of $41,473 (inflation indexed to 2011 dollars) and a median family income of $63,435. Male full-time year round workers had a median income of $42,865, versus $36,351 for females. The per capita income for the county was $25,172; 23.6% of the population was living below the poverty line.[24]

Languages

As of 2010, 86.43% of the population spoke English as their primary language, while Spanish was spoken by 6.38%, 1.18% spoke Chinese, 0.57% were speakers of Korean, and 0.52% spoke French as their native language.[25]

.jpg.webp)

Education

The entire county of Alachua is served by the Alachua County School District, which has some 47 different institutions in the county. Alachua county is also home to the University of Florida and Santa Fe College.

Library

The Alachua County Library District is an independent special taxing district and the sole provider of public library service to approximately 250,000 citizens of Alachua County, Florida. This includes all of the incorporated municipalities in the county. It maintains a Headquarters Library and four other branches in Gainesville. These locations include the Millhopper Branch in northwest Gainesville, the Tower Road Branch in unincorporated Alachua county southwest of Gainesville, the Library Partnership Branch in northeast Gainesville, and the Cone Park Branch in east Gainesville. The district also operates branches in the Alachua County municipalities of Alachua, Archer, Hawthorne, High Springs, Micanopy, Newberry, and Waldo, as well as a branch at the Alachua County Jail. The district operates two bookmobiles which visit more than 25 locations in the county from two to five times a month.[26][27][28]

Library history

The Alachua County Library District traces its origins to 1905, when the Twentieth Century Club in Gainesville started a subscription library. The Gainesville Public Library, a subscription library operated by the Library Association, opened in 1906. The Twentieth Century Club donated the books from its subscription library, and the new library also received books from the library of the East Florida Seminary, which had been absorbed by the newly founded University of Florida.

The Gainesville Public Library became a free library in 1918, supported by funds from city taxes from all residents, but it was available only to whites. The building was constructed with the aid of a Carnegie library grant. The library became a department of the City of Gainesville in 1949. It was not until 1953 and opening of the Carver Branch Library that African Americans in the city had access to a library, as public facilities were still segregated. The Carver Branch closed in 1969, after the main library had been desegregated.

In 1958, the City of Gainesville and Alachua County agreed to jointly operate the library for the whole county. Branch libraries were opened in High Springs, Hawthorne and Micanopy the next year, and a bookmobile was put into service. Alachua County joined with Bradford County to operate the Santa Fe Regional Library. After Bradford County withdrew from the Regional Library, the Alachua County Library District was formally established in 1986. The Millhopper and Tower Road branches opened in 1992, and the branches in Alachua, Archer, Newberry and Waldo were all opened by 1997. The Library Partnership Branch opened in 2009, and the Cone Park Branch in 2011. A new, permanent location for the Cone Park Branch Library was opened near the Eastside Community Center in Gainesville on December 14, 2013.[29][30][31]

Transportation

Airports

- Gainesville Regional Airport-Gainesville

- Flying Ten Airport-Archer

- Oak Tree Landing Airport-High Springs

- Gleim Field Airport-Gainesville

Politics

Voter registration

As of February 28, 2019, the county had a strong Democratic plurality, with large Republican and independent minorities.[32]

| Name | Number of voters | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | 88,209 | 47.80 | |

| Republican | 50,662 | 27.45 | |

| Independent | 43,858 | 23.77 | |

| Other | 1,814 | 0.98 | |

| Total | 184,543 | ||

Statewide elections

Like many other counties containing large state universities, Alachua County regularly supports the Democratic Party. It has voted for the Democratic candidate for president in the past seven elections. The county last supported a Republican presidential candidate in 1988, when it narrowly went for George H. W. Bush.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 35.6% 50,972 | 62.7% 89,704 | 1.7% 2,371 |

| 2016 | 36.0% 46,834 | 58.3% 75,820 | 5.7% 7,446 |

| 2012 | 40.4% 48,797 | 57.7% 69,699 | 1.9% 2,277 |

| 2008 | 38.5% 48,513 | 59.9% 75,565 | 1.5% 1,889 |

| 2004 | 42.9% 47,762 | 56.1% 62,504 | 1.0% 1,062 |

| 2000 | 39.8% 34,135 | 55.3% 47,380 | 4.9% 4,242 |

| 1996 | 34.0% 25,316 | 53.9% 40,161 | 12.1% 9,039 |

| 1992 | 29.9% 22,813 | 49.6% 37,888 | 20.5% 15,671 |

| 1988 | 50.1% 30,153 | 48.8% 29,396 | 1.1% 664 |

| 1984 | 53.5% 30,609 | 46.4% 26,584 | 0.1% 60 |

| 1980 | 38.6% 19,804 | 52.3% 26,849 | 9.2% 4,711 |

| 1976 | 34.9% 15,546 | 62.6% 27,895 | 2.6% 1,137 |

| 1972 | 56.5% 22,536 | 43.3% 17,245 | 0.2% 80 |

| 1968 | 34.0% 9,670 | 35.4% 10,060 | 30.6% 8,696 |

| 1964 | 45.3% 11,151 | 54.7% 13,483 | |

| 1960 | 52.1% 10,072 | 48.0% 9,279 | |

| 1956 | 53.5% 7,939 | 46.5% 6,889 | |

| 1952 | 58.5% 8,432 | 41.5% 5,990 | |

| 1948 | 23.6% 2,403 | 36.8% 3,745 | 39.6% 4,034 |

| 1944 | 22.7% 1,690 | 77.3% 5,755 | |

| 1940 | 17.0% 1,372 | 83.0% 6,714 | |

| 1936 | 15.7% 890 | 84.3% 4,788 | |

| 1932 | 21.9% 983 | 78.1% 3,506 | |

| 1928 | 2.4% 132 | 35.0% 1,965 | 62.6% 3,515[34] |

| 1924 | 18.9% 528 | 71.4% 1,995 | 9.7% 271 |

| 1920 | 24.5% 1,119 | 72.5% 3,310 | 3.0% 135 |

| 1916 | 17.3% 440 | 79.8% 2,030 | 3.0% 75 |

| 1912 | 12.8% 221 | 75.3% 1,304 | 11.9% 206 |

| 1908 | 33.8% 686 | 61.0% 1,239 | 5.2% 105 |

| 1904 | 28.2% 543 | 66.4% 1,277 | 5.4% 103 |

| 1900 | 19.0% 334 | 76.7% 1,346 | 4.3% 76 |

| 1896 | 28.7% 645 | 68.8% 1,545 | 2.5% 55 |

| 1892 | 84.3% 1,447 | 15.7% 270 |

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 35.79% 41,278 | 63.05% 72,711 | 1.04% 1,203 |

| 2014 | 39.79% 31,097 | 56.37% 44,052 | 3.84% 3,004 |

| 2010 | 38.03% 28,129 | 59.40% 43,933 | 2.57% 1,899 |

| 2006 | 42.74% 30,139 | 54.94% 38,741 | 2.32% 1,636 |

| 2002 | 41.38% 29,118 | 57.73% 40,621 | 0.90% 629 |

| 1998 | 44.79% 23,812 | 55.19% 29,343 | 0.03% 14 |

| 1994 | 38.16% 21,624 | 61.82% 35,030 | 0.01% 7 |

Landfills

Alachua County is the site of five closed landfills—Southwest Landfill, Southeast Landfill, Northwest Landfill, Northeast Landfill, and Northeast Auxiliary Landfill.[36] Since 1999, all solid waste from Alachua County has been hauled to the New River Solid Waste Facility in Raiford, in neighboring Union County.[37]

Communities

| # | Incorporated Community | Designation | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Alachua | City | 9,561 |

| 6 | Archer | City | 1,158 |

| 1 | Gainesville | City | 128,460 |

| 5 | Hawthorne | City | 1,471 |

| 3 | High Springs | City | 5,672 |

| 9 | La Crosse | Town | 372 |

| 8 | Micanopy | Town | 622 |

| 4 | Newberry | City | 6,249 [38] |

| 7 | Waldo | City | 1,024 |

Unincorporated communities

- Arredondo

- Bland

- Campville

- Cross Creek

- Earleton

- Evinston, partly in Marion County

- Fairbanks

- Grove Park

- Hague

- Haile

- Haile Plantation

- Hasan

- Island Grove

- Jonesville

- Melrose, partly in Bradford, Clay, and Putnam counties

- Newnansville

- Orange Heights

- Rochelle

- Santa Fe

- Tioga

- Traxler

- Wacahoota, partly in Marion County

- Windsor

See also

Notes

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1994). Archaeology of Precolumbian Florida. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida. pp. 43, 62–64, 228, 335. ISBN 978-0-8130-1273-5.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1998). Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. pp. 90–91, 173–176, 185–187, 232–237. ISBN 978-0-8130-1636-8.

- Hann, John H. (1996). A History of the Timucua Indians and Missions. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. pp. 193–194. ISBN 978-0-8130-1424-1.

- Simpson, J. Clarence (1956). Florida Place-Names of Indian Derivation. Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Geological Survey. pp. 20–21.

- Monaco, Chris (Summer 2000). "Fort Mitchell and the Settlement of the Alachua Country". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 79 (1): 1–25. JSTOR 30149405.

- Simpson, J. Clarence (1956). Mark F. Boyd (ed.). Florida Place-Names of Indian Derivation. Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Geological Survey. pp. 20–21.

- Andersen, Lars (2001). Payne's Prairie: A History of the Great Savanna. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press, Inc. pp. 47, 51–52, 59–66. ISBN 978-1-56164-225-0.

- Patrick, Rembert W. (1954). Florida Fiasco: Rampant Rebels on the Georgia-Florida Border 1810–1815. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. pp. 230–234. LCCN 53-13265.

- LaCoe, Norm (1974). "The Alachua Frontier". In Opdyke, John B. (ed.). Alachua County: A Sesquicentennial Tibute. Gainesville, Florida: The Alachua County Historical Commission. pp. 7–15.

- "History of Alachua". Alachua Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- Nicole Dan, "Newberry Lynchings: Should They Be Memorialized?", WUFT-TV, 6 December 2017; accessed 20 March 2018

- Chandler, Billy Jaynes (October 1994). "Harmon Murray: Black Desperado in Later Nineteenth-Century Florida". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 73 (2): 163–174. JSTOR 30146739.

- Dan, Nicole (27 September 2017). "At Least 21 Lynched In Alachua County, Historical Commission Confirms". WUFT-TV. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- "Lynching in America/ Supplement: Lynchings by County, 3rd Edition, 2015, p.2" (PDF).

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- "2007-2011 American Community Survey". US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12.

- "Modern Language Association Data Center Results, Alachua County, Florida". Modern Language Association. Archived from the original on 2006-06-19. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- "Locations | Alachua County Library District". www.aclib.us. Retrieved 2015-12-04.

- "Alachua County Sheriff's Office". www.alachuasheriff.org. Retrieved 2015-12-04.

- "Bookmobile stops | Alachua County Library District". www.aclib.us. Retrieved 2015-12-04.

- "Florida Library History Project".

- "Alachua County Library District Heritage Collection". heritage.acld.lib.fl.us. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-12-04.

- "Cone Park library hosting grand opening". Gainesville.com. Retrieved 2015-12-04.

- "Voter Registration - By County and Party". dos.myflorida.com. Archived from the original on 2019-04-06. Retrieved 2019-04-06.

- "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections".

- The leading "other" candidate, Socialist Norman Thomas, received 1,806 votes while the Communist candidate, William Z. Foster, received 1,709 votes.

- "Election Results".

- "Landfills". Alachua County, Florida. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- "Brief History of the Environmental Park". Alachua County, Florida. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- https://www.bebr.ufl.edu/population