Air France Flight 447

Air France Flight 447 (AF447 or AFR447[lower-alpha 1]) was a scheduled international passenger flight from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to Paris, France. On 1 June 2009, the Airbus A330 serving the flight stalled and did not recover, eventually crashing into the Atlantic Ocean at 02:14 UTC, killing all 228 passengers and crew.

F-GZCP, the aircraft involved, seen in 2007 | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 1 June 2009 |

| Summary | Entered high-altitude stall; impacted ocean |

| Site | Atlantic Ocean near waypoint TASIL[1]:9 3°03′57″N 30°33′42″W |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Airbus A330-203 |

| Operator | Air France |

| IATA flight No. | AF447 |

| ICAO flight No. | AFR447 |

| Call sign | AIRFRANS 447 |

| Registration | F-GZCP |

| Flight origin | Rio de Janeiro/Galeão International Airport |

| Destination | Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport |

| Occupants | 228 |

| Passengers | 216 |

| Crew | 12 |

| Fatalities | 228 |

| Survivors | 0 |

The Brazilian Navy recovered the first major wreckage, and two bodies, from the sea within five days of the accident, but the initial investigation by France's Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety (BEA) was hampered because the aircraft's flight recorders were not recovered from the ocean floor until May 2011, nearly two years later.

The BEA's final report, released at a news conference on 5 July 2012, concluded that the aircraft crashed after temporary inconsistencies between the airspeed measurements—likely due to the aircraft's pitot tubes being obstructed by ice crystals—caused the autopilot to disconnect, after which the crew reacted incorrectly and ultimately caused the aircraft to enter an aerodynamic stall, from which it did not recover.[2]:79[3]:7[4] The accident is the deadliest in the history of Air France, as well as the deadliest aviation accident involving the Airbus A330.[5]

Aircraft

The aircraft involved in the accident was a 4 year old Airbus A330-203, with manufacturer serial number (MSN) 660, registered as F-GZCP. Its first flight was on 25 February 2005, and it was delivered 2 months later to the airline on 18 April 2005. At the time of the crash, it was Air France's newest A330.[6][7] The aircraft was powered by two General Electric CF6-80E1A3 engines with a maximum thrust of 68,530 / 60,400 lb (take-off/max continuous),[8] giving it a cruise speed range of Mach 0.82–0.86 (871–913 km/h, 470–493 knots, 540–566 mph), at 41,000 feet (12 km) of altitude and a range of 12,500 km (6750 nmi, 7760 statute miles). On 17 August 2006, this A330 was involved in a ground collision with Airbus A321-211 F-GTAM, at Charles de Gaulle Airport, Paris. F-GTAM was substantially damaged while F-GZCP suffered only minor damage.[9] The aircraft underwent a major overhaul on 16 April 2009, and at the time of the accident had accumulated about 18,870 flying hours.[10]

Passengers and crew

| Nationality | Passengers | Crew | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina[11] | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Austria | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Belgium | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Brazil | 58 | 1 | 59 |

| Canada | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| China | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Croatia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Denmark | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Estonia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| France | 61 | 11 | 72 |

| Gabon | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Germany | 26 | 0 | 26 |

| Hungary | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Iceland | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ireland[12] | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Italy | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Lebanon | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Morocco | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Netherlands[13] | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Norway[14] | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Philippines | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Poland | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Romania[15] | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Russia[16] | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Slovakia[17] | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| South Africa | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| South Korea | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Spain[18] | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Sweden[19] | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Switzerland[20] | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Turkey[21] | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| United Kingdom | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| United States[22] | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Total (33 nationalities) | 216 | 12 | 228 |

| Notes: Nationalities shown are as stated by Air France on 1 June 2009.[23] Attributing nationality was complicated by the holding of multiple citizenship by several passengers. Passengers who had citizenship in one country but were attributed to another country by Air France are indicated with parentheses (). | |||

The aircraft was carrying 216 passengers, three aircrew and nine cabin crew in two cabins of service.[5][24][25] Among the 216 passengers were 126 men, 82 women and eight children (including one infant).[26]

There were three pilots in the aircrew:[2]:24–29

- The captain, 58-year-old Marc Dubois (PNF-Pilot Not Flying)[2]:21 had joined Air France (at the time, Air Inter)[27] in February 1988 and had 10,988 flying hours, of which 6,258 were as captain, including 1,700 hours on the Airbus A330; he had carried out 16 rotations in the South America sector since arriving in the A330/A340 division in 2007.[28]

- The first officer, co-pilot in left seat, 37-year-old David Robert (PNF-Pilot Not Flying) had joined Air France in July 1998 and had 6,547 flying hours, of which 4,479 hours were on the Airbus A330; he had carried out 39 rotations in the South America sector since arriving in the A330/A340 division in 2002. Robert had graduated from École Nationale de l'Aviation Civile (ENAC), one of the elite Grandes Écoles, and had transitioned from a pilot to a management job at the airline's operations center. He served as a pilot on this flight in order to maintain his flying credentials.[29][28]

- The first officer, co-pilot in right seat, 32-year-old Pierre-Cédric Bonin (PF-Pilot Flying) had joined Air France in October 2003 and had 2,936 flight hours, of which 807 hours were on the Airbus A330; he had carried out five rotations in the South America sector since arriving in the A330/A340 division in 2008.[28] His wife Isabelle, a physics teacher, was also on board.[30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37]

Of the 12 crew members (including aircrew and cabin crew), 11 were French and one was Brazilian.[38]

The majority of passengers were French, Brazilian, or German citizens.[39][40][23] The passengers included business and holiday travelers.[41]

Air France established a crisis center[42] at Terminal 2D for the approximately 60 to 70 relatives and friends who arrived at Charles de Gaulle Airport to pick up arriving passengers. However, many of the passengers on Flight 447 were connecting to other destinations worldwide. In the days that followed, Air France contacted close to 2,000 people who were related to, or friends of, the victims.[43]

On 20 June 2009, Air France announced that each victim's family would be paid roughly €17,500 in initial compensation.[44]

Notable passengers

- Prince Pedro Luiz of Orléans-Bragança, third in succession to the abolished throne of Brazil and grandnephew of Grand Duke Jean of Luxembourg.[45][46] He had dual Brazilian–Belgian citizenship. He was returning home to Luxembourg from a visit to his relatives in Rio de Janeiro.[47][48]

- Giambattista Lenzi, member of the Regional Council of Trentino-Alto Adige[49]

- Silvio Barbato, composer and former conductor of the symphony orchestras of the Cláudio Santoro National Theater in Brasilia and the Rio de Janeiro Municipal Theatre; he was en route to Kyiv for engagements there.[50][51]

- Octavio Augusto Ceva Antunes, professor of chemistry and Pharmaceutics at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro[52]

- Fatma Ceren Necipoğlu, Turkish classical harpist and academic of Anadolu University in Eskişehir; she was returning home via Paris after performing at the fourth Rio Harp Festival.[53]

- Izabela Maria Furtado Kestler, professor of German Studies at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro[54]

- Pablo Dreyfus from Argentina, a campaigner for controlling illegal arms and the illegal drugs trade.[55]

Accident

The aircraft departed from Rio de Janeiro–Galeão International Airport on 31 May 2009 at 19:29 Brazilian Standard Time (22:29 UTC),[2]:21 with a scheduled arrival at Paris-Charles de Gaulle Airport at 11:03 Central European Summer Time (09:03 UTC) the following day (estimated flight time of 10:34).[56] Voice contact with the aircraft was lost around at around 01:35 UTC, 3 hours and 6 minutes after departure. The last message reported that the aircraft had passed waypoint INTOL (1°21′39″S 32°49′53″W), located 565 km (351 mi; 305 nmi) off Natal, on Brazil's north-eastern coast.[57] The aircraft left Brazilian Atlantic radar surveillance at 01:49 UTC,[2]:49[58] and entered a communication dead zone.[29][2]

The Airbus A330 is designed to be flown by a crew of two pilots. However, the 13-hour "duty time" (the total flight duration as well as pre-flight preparation) required for the Rio-Paris route exceeded the 10 hours permitted before a pilot must take a break as dictated by Air France's procedures. To comply with these procedures, Flight 447 was crewed by three pilots: a captain and two first officers.[59] With three pilots on board, each pilot could take a break in the A330's rest cabin located behind the cockpit.[60]

In accordance with common practice, captain Dubois sent one of the co-pilots for the first rest period with the intention of taking the second break himself.[61] At 01:55 UTC, he woke up first officer Robert and said: "... he's going to take my place". After attending the briefing between the two co-pilots, the captain left the cockpit to rest at 02:01:46 UTC. At 02:06 UTC, the pilot warned the cabin crew that they were about to enter an area of turbulence. About two to three minutes later, the aircraft encountered icing conditions. The cockpit voice recorder (CVR) recorded sounds akin to hail or graupel on the outside of the aircraft, and ice crystals began to accumulate in the pitot tubes, which measure airspeed.[62] The other first officer Bonin turned the aircraft slightly to the left and decreased its speed from Mach 0.82 to Mach 0.8, which was the recommended speed to penetrate through turbulence. The engine anti-ice system was also turned on.[63]

At 02:10:05 UTC, the autopilot disengaged, most likely due to hailstones blocking the pitot tubes, and the aircraft transitioned from "normal law" to "alternate law 2".[64] The engines' auto-thrust systems disengaged three seconds later. As the pilot flying, first officer Bonin took over control of the aircraft, using the command language "I have the controls." Without the auto-pilot, the aircraft started to roll to the right due to turbulence, and Bonin reacted by deflecting his side-stick to the left. One consequence of the change to alternate law was an increase in the aircraft's sensitivity to roll, and the pilot's input over-corrected. During the next 30 seconds, the aircraft rolled alternately left and right as Bonin adjusted to the altered handling characteristics of the aircraft.[65] At the same time he abruptly pulled back on his side-stick, raising the nose. This action has been described as unnecessary and excessive under the circumstances.[66] The aircraft's stall warning briefly sounded twice due to the angle of attack tolerance being exceeded, and the aircraft's indicated airspeed dropped sharply from 274 knots (507 km/h; 315 mph) to 52 knots (96 km/h; 60 mph). The aircraft's angle of attack increased, and subsequently began to climb above its cruising altitude of 35,000 ft (FL350). During this ascent, the aircraft attained vertical speeds well in excess of the typical rate of climb for the Airbus A330, which usually ascend at rates no greater than 2000 feet per minute (10.16 m/s). The aircraft experienced a peak vertical speed close to 7,000 feet per minute (36 m/s; 130 km/h),[65] which occurred as first officer Bonin brought the rolling movements under control.

At 02:10:34 UTC, after displaying incorrectly for half a minute, the left-side instruments recorded a sharp rise in airspeed to 223 knots (413 km/h; 257 mph), as did the Integrated Standby Instrument System (ISIS) 33 seconds later.[67] The right-side instruments were not recorded by the recorder. The icing event had lasted for just over a minute,[68][69][2]:198[70] yet first officer Bonin continued to make nose-up inputs. The trimmable horizontal stabilizer (THS) moved from three to 13 degrees nose-up in about one minute, and remained in the latter position until the end of the flight.

At 02:11:10 UTC, the aircraft had climbed to its maximum altitude of around 38,000 feet (12,000 m). At this point, the aircraft's angle of attack was 16 degrees, and the engine thrust levers were in the fully forward takeoff/go-around detent (TOGA). As the aircraft began to descend, the angle of attack rapidly increased toward 30 degrees. A second consequence of the reconfiguration into alternate law was that the stall protection no longer operated, whereas in normal law the aircraft's flight management computers would have acted to prevent such a high angle of attack.[71] The wings lost lift and the aircraft began to stall.[3]

Confused, first officer Bonin exclaimed "[Expletive] I don't have control of the airplane any more now", and two seconds later, "I don't have control of the airplane at all!"[28] First officer Robert responded to this by saying, "controls to the left", and took over control of the aircraft.[72][31] Robert pushed his side-stick forward to lower the nose and recover from the stall; however, Bonin was still pulling his side-stick back. The inputs cancelled each other out and triggered an aural "dual input" warning.

At 02:11:40 UTC, captain Dubois re-entered the cockpit after being summoned by first officer Robert. Noticing the various alarms going off, he asked the two crew members, "er what are you (doing)?"[31] The angle of attack had then reached 40 degrees, and the aircraft had descended to 35,000 feet (11,000 m) with the engines running at almost 100% N1 (the rotational speed of the front intake fan, which delivers most of a turbofan engine's thrust). The stall warnings stopped, as all airspeed indications were now considered invalid by the aircraft's computer due to the high angle of attack.[73] The aircraft had its nose above the horizon but was descending steeply.

Roughly 20 seconds later, at 02:12 UTC, Bonin decreased the aircraft's pitch slightly. Airspeed indications became valid, and the stall warning sounded again; it then sounded intermittently for the remaining duration of the flight, stopping only when the pilots increased the aircraft's nose-up pitch. From there until the end of the flight, the angle of attack never dropped below 35 degrees. From the time the aircraft stalled until its impact into the ocean, the engines were primarily developing either 100 percent N1 or TOGA thrust, though they were briefly spooled down to about 50 percent N1 on two occasions. The engines always responded to commands and were developing in excess of 100 percent N1 when the flight ended. First officer Robert responded to captain Dubois by saying: "We've lost all control of the aeroplane, we don’t understand anything, we’ve tried everything".[31] Soon after this, Robert said to himself, "climb" four consecutive times. Bonin heard this and replied, "But I've been at maximum nose-up for a while!" When Captain Dubois heard this, he realized Bonin was causing the stall, and shouted, "No no no, don't climb! No No No!"[74][31]

When first officer Robert heard this, he told Bonin to give the control of the airplane to him.[2] In response to this, Bonin temporarily gave the controls to Robert.[31][74][2] Robert pushed his side stick forward to try to regain lift for the airplane to climb out of the stall. However, the aircraft was too low to recover from the stall. Shortly thereafter, the ground proximity warning system sounded an alarm, warning the crew about the aircraft's imminent crash with the ocean. In response, Bonin (without informing his colleagues) pulled his side stick all the way back again,[31][2] and said, "[Expletive] We're going to crash! This can't be true. But what's happening?"[74][31][2][75][28] The last recording on the CVR was captain Dubois saying: "(ten) degrees pitch attitude."

The flight data recorders stopped recording at 02:14:28 UTC, 3 hours and 45 minutes after takeoff. At that point, the aircraft's ground speed was recorded as 107 knots (198 km/h; 123 mph), and that the aircraft was descending at 10,912 feet per minute (55.43 m/s) (108 knots (200 km/h; 124 mph) of vertical speed). Its pitch was 16.2 degrees nose-up, with a roll angle of 5.3 degrees to the left. During its descent, the aircraft had turned more than 180 degrees to the right to a compass heading of 270 degrees. The aircraft remained stalled during its entire 3-minute 30 second descent from 38,000 feet (12,000 m).[76] The aircraft struck the ocean belly-first at a speed of 152 knots (282 km/h; 175 mph), comprising vertical and horizontal components of 108 knots (200 km/h; 124 mph) and 107 knots (198 km/h; 123 mph) respectively. All 228 passengers and crew on board died on impact from extreme trauma and the aircraft was destroyed.[77][2][75]

Automated messages

Air France's A330s are equipped with a communications system, Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS), which enables them to transmit data messages via VHF or satellite.[lower-alpha 2] ACARS can be used by the aircraft's on-board computers to send messages automatically, and F-GZCP transmitted a position report approximately every ten minutes. Its final position report at 02:10:34 gave the aircraft's coordinates as 2°59′N 30°35′W.[lower-alpha 3]

In addition to the routine position reports, F-GZCP's Centralized Maintenance System sent a series of messages via ACARS in the minutes immediately prior to its disappearance.[78][79][80] These messages, sent to prepare maintenance workers on the ground prior to arrival, were transmitted between 02:10 UTC and 02:15 UTC,[81] and consisted of five failure reports and nineteen warnings.[82][83][84][85]

Among the ACARS transmissions at 02:10 is one message that indicates a fault in the pitot-static system.[81][85] Bruno Sinatti, president of Alter, Air France's third-biggest pilots' union, stated that "Piloting becomes very difficult, near impossible, without reliable speed data."[86] The 12 warning messages with the same time code indicate that the autopilot and auto-thrust system had disengaged, that the TCAS was in fault mode, and flight mode went from 'normal law' to 'alternate law.'[87][88]

The remainder of the messages occurred from 02:11 UTC to 02:14 UTC, containing a fault message for an Air Data Inertial Reference Unit (ADIRU) and the Integrated Standby Instrument System (ISIS).[88][89] At 02:12 UTC, a warning message NAV ADR DISAGREE indicated that there was a disagreement between the three independent air data systems.[lower-alpha 4] At 02:13 UTC, a fault message for the flight management guidance and envelope computer was sent.[90] One of the two final messages transmitted at 02:14 UTC was a warning referring to the air data reference system, the other ADVISORY was a "cabin vertical speed warning", indicating that the aircraft was descending at a high rate.[78][91][92][93]

Weather conditions

Weather conditions in the mid-Atlantic were normal for the time of year, and included a broad band of thunderstorms along the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ).[94] A meteorological analysis of the area surrounding the flight path showed a mesoscale convective system extending to an altitude of around 50,000 feet (15,000 m) above the Atlantic Ocean before Flight 447 disappeared.[95][96][97][98] During its final hour, Flight 447 encountered areas of light turbulence.[99]

Commercial air transport crews routinely encounter this type of storm in this area.[100] With the aircraft under the control of its automated systems, one of the main tasks occupying the cockpit crew was that of monitoring the progress of the flight through the ITCZ, using the on-board weather radar to avoid areas of significant turbulence.[101] Twelve other flights had recently shared more or less the same route that Flight 447 was using at the time of the accident.[102][103]

Search and recovery

Surface search

Flight 447 was due to pass from Brazilian airspace into Senegalese airspace at approximately 02:20 (UTC) on 1 June, and then into Cape Verdean airspace at approximately 03:45. Shortly after 04:00, when the flight had failed to contact air traffic control in either Senegal or Cape Verde, the controller in Senegal attempted to contact the aircraft. When he received no response, he asked the crew of another Air France flight (AF459) to try to contact AF447; this also met with no success.[104]

After further attempts to contact Flight 447 were unsuccessful, an aerial search for the missing Airbus commenced from both sides of the Atlantic. Brazilian Air Force aircraft from the archipelago of Fernando de Noronha and French reconnaissance aircraft based in Dakar, Senegal led the search.[26] They were assisted by a Casa 235 maritime patrol aircraft from Spain[105] and a United States Navy Lockheed Martin P-3 Orion anti-submarine warfare and maritime patrol aircraft.[106][107]

By early afternoon on 1 June, officials with Air France and the French government had already presumed the aircraft had been lost with no survivors. An Air France spokesperson told L'Express that there was "no hope for survivors",[108][109] and French President Nicolas Sarkozy announced there was almost no chance anyone survived.[110] On 2 June at 15:20 (UTC), a Brazilian Air Force Embraer R-99A spotted wreckage and signs of oil, possibly jet fuel, strewn along a 5 km (3 mi; 3 nmi) band 650 km (400 mi; 350 nmi) north-east of Fernando de Noronha Island, near the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago. The sighted wreckage included an aircraft seat, an orange buoy, a barrel, and "white pieces and electrical conductors".[111][112] Later that day, after meeting with relatives of the Brazilians on the aircraft, Brazilian Defence Minister Nelson Jobim announced that the Air Force believed the wreckage was from Flight 447.[113][114] Brazilian vice-president José Alencar (acting as president since Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was out of the country) declared three days of official mourning.[114][115]

Also on 2 June, two French Navy vessels, the frigate Ventôse and helicopter-carrier Mistral, were en route to the suspected crash site. Other ships sent to the site included the French research vessel Pourquoi Pas?, equipped with two mini-submarines able to descend to 6,000 m (20,000 ft),[116][117] since the area of the Atlantic in which the aircraft went down was thought to be as deep as 4,700 m (15,400 ft).[118][119]

On 3 June, the first Brazilian Navy (the "Marinha do Brasil" or MB) ship, the patrol boat Grajaú, reached the area in which the first debris was spotted. The Brazilian Navy sent a total of five ships to the debris site; the frigate Constituição and the corvette Caboclo were scheduled to reach the area on 4 June, the frigate Bosísio on 6 June and the replenishment oiler Almirante Gastão Motta on 7 June.[120][121]

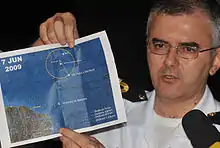

Early on 6 June 2009, five days after Flight 447 disappeared, two male bodies, the first to be recovered from the crashed aircraft, were brought on board the Caboclo[122] along with a seat, a nylon backpack containing a computer and vaccination card, and a leather briefcase containing a boarding pass for the Air France flight. Initially, media (including Los Angeles Times, Boston Globe and Chicago Tribune) cited unnamed investigators in their reporting that the recovered bodies were naked, which implied the plane had broken up at high altitude.[123] However, airborne fragmentation of the aircraft ultimately was refuted by investigators.[124] At this point, on the evidence of the recovered bodies and materials, investigators confirmed the plane had crashed killing everyone on board.[125][126] The following day, 7 June, search crews recovered the Airbus's vertical stabilizer, the first major piece of wreckage to be discovered. Pictures of this part being lifted onto the Constituição became a poignant symbol of the loss of the Air France craft.[1][127]

The search and recovery effort reached its peak over the next week or so, as the number of personnel mobilized by the Brazilian military exceeded 1100.[lower-alpha 5][128] Fifteen aircraft (including two helicopters) were devoted to the search mission.[129] The Brazilian Air Force Embraer R99 flew for more than 100 hours, and electronically scanned more than a million square kilometers of ocean.[130] Other aircraft involved in the search scanned, visually, 320,000 square kilometres (120,000 sq mi; 93,000 sq nmi) of ocean and were used to direct Navy vessels involved in the recovery effort.[128]

By 16 June 2009, 50 bodies had been recovered from a wide area of the ocean.[131][132][133] They were transported to shore, first by the frigates Constituição and Bosísio to the islands of Fernando de Noronha, and thereafter by air to Recife for identification.[133][134][135][136] Pathologists identified all 50 bodies recovered from the crash site, including that of the captain, by using dental records and fingerprints.[137][138][139] The search teams logged the time and location of every find in a database which, by the time the search ended on 26 June, catalogued 640 items of debris from the aircraft.[131]

The BEA documented the timeline of discoveries in its first interim report.[140][141][142]

Underwater search

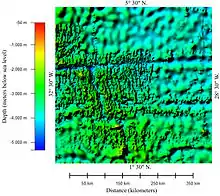

On 5 June 2009, the French nuclear submarine Émeraude was dispatched to the crash zone, arriving in the area on the 10th. Its mission was to assist in the search for the missing flight recorders or "black-boxes" that might be located at great depth.[143] The submarine would use its sonar to listen for the ultrasonic signal emitted by the black boxes' "pingers",[144] covering 13 sq mi (34 km2; 9.8 sq nmi) per day. The Émeraude was to work with the mini-sub Nautile, which can descend to the ocean floor. The French submarines would be aided by two U.S. underwater audio devices capable of picking up signals at a depth of 20,000 ft (6,100 m).[145]

Following the end of the search for bodies, the search continued for the Airbus's "black boxes"—the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) and the Flight Data Recorder (FDR). French Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety (BEA) chief Paul-Louis Arslanian said that he was not optimistic about finding them since they might have been under as much as 3,000 m (9,800 ft) of water, and the terrain under this portion of the ocean was very rugged.[146] Investigators were hoping to find the aircraft's lower aft section, for that was where the recorders were located.[147] Although France had never recovered a flight recorder from such depths,[146] there was precedent for such an operation: in 1988, an independent contractor recovered the CVR of South African Airways Flight 295 from a depth of 4,900 m (16,100 ft) in a search area of between 80 and 250 square nautical miles (270 and 860 km2; 110 and 330 sq mi).[148][149] The Air France flight recorders were fitted with water-activated acoustic underwater locator beacons or "pingers", which should have remained active for at least 30 days, giving searchers that much time to locate the origin of the signals.[150]

France requested two "towed pinger locator hydrophones" from the United States Navy to help find the aircraft.[116] The French nuclear submarine and two French-contracted ships (the Fairmount Expedition and the Fairmount Glacier, towing the U.S. Navy listening devices) trawled a search area with a radius of 80 kilometres (50 mi), centred on the aircraft's last known position.[151][152] By mid-July, recovery of the black boxes still had not been announced. The finite beacon battery life meant that, as the time since the crash elapsed, the likelihood of location diminished.[153] In late July, the search for the black boxes entered its second phase, with a French research vessel resuming the search using a towed sonar array.[154] The second phase of the search ended on 20 August without finding wreckage within a 75 km (47 mi; 40 nmi) radius of the last position, as reported at 02:10.[155]

The third phase of the search for the recorders lasted from 2 April until 24 May 2010,[156][157][158] and was conducted by two ships, the Anne Candies and the Seabed Worker. The Anne Candies towed a U.S. Navy sonar array, while the Seabed Worker operated three robot submarines AUV ABYSS (a REMUS AUV type).[156][159][160][161] Air France and Airbus jointly funded the third phase of the search.[162][163] The search covered an area of 6,300 square kilometres (2,400 sq mi; 1,800 sq nmi), mostly to the north and north-west of the aircraft's last known position.[156][160][164] The search area had been drawn up by oceanographers from France, Russia, Great Britain and the United States combining data on the location of floating bodies and wreckage, and currents in the mid-Atlantic in the days immediately after the crash.[165][166][167] A smaller area to the south-west was also searched, based on a re-analysis of sonar recordings made by Émeraude the previous year.[168][169][170] The third phase of the search ended on 24 May 2010 without any success, though the BEA says that the search 'nearly' covered the whole area drawn up by investigators.[156]

2011 search and recovery

In July 2010, the U.S.-based search consultancy Metron, Inc. had been engaged to draw up a probability map of where to focus the search, based on prior probabilities from flight data and local condition reports, combined with the results from the previous searches. The Metron team used what it described as "classic" Bayesian search methods, an approach that had previously been successful in the search for the submarine USS Scorpion and SS Central America. Phase 4 of the search operation started close to the aircraft's last known position, which was identified by the Metron study as being the most likely resting place of flight 447.[171][172]

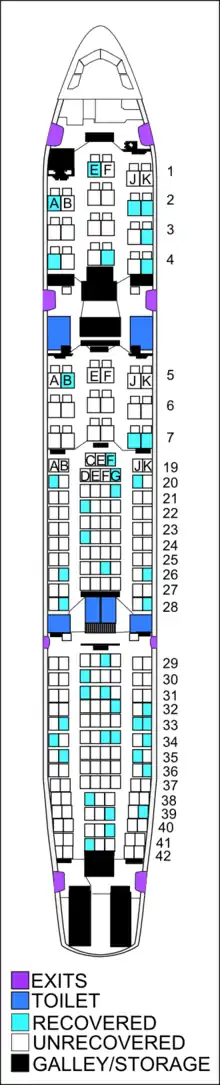

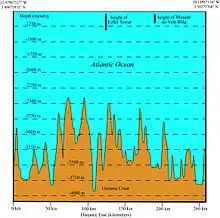

Within a week of resuming of the search operation, on 3 April 2011, a team led by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution operating full ocean depth autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) owned by the Waitt Institute discovered, by means of sidescan sonar, a large portion of the debris field from flight AF447.[171] Further debris and bodies, still trapped in the partly intact remains of the aircraft's fuselage, were at a depth of 3,980 metres (2,180 fathoms; 13,060 ft).[173] The debris was found lying in a relatively flat and silty area of the ocean floor (as opposed to the extremely mountainous topography originally believed to be AF447's final resting place). Other items found were engines, wing parts and the landing gear.[174]

The debris field was described as "quite compact", measuring 200 by 600 metres (660 by 1,970 ft) and a short distance north of where pieces of wreckage had been recovered previously, suggesting the aircraft hit the water largely intact.[175] The French Ecology and Transportation Minister Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet stated the bodies and wreckage would be brought to the surface and taken to France for examination and identification.[176] The French government chartered the Île de Sein to recover the flight recorders from the wreckage.[177][178] An American Remora 6000 remotely operated vehicle (ROV)[lower-alpha 7] and operations crew from Phoenix International experienced in the recovery of aircraft for the United States Navy were on board the Île de Sein.[179][180]

Île de Sein arrived at the crash site on 26 April, and during its first dive, the Remora 6000 found the flight data recorder chassis, although without the crash-survivable memory unit.[181][182] On 1 May the memory unit was found and lifted on board the Île de Sein by the ROV.[183] The aircraft's cockpit voice recorder was found on 2 May 2011, and was raised and brought on board the Île de Sein the following day.[184]

On 7 May, the flight recorders, under judicial seal, were taken aboard the French Navy patrol boat La Capricieuse for transfer to the port of Cayenne. From there they were transported by air to the BEA's office in Le Bourget near Paris for data download and analysis. One engine and the avionics bay, containing onboard computers, had also been raised.[185]

By 15 May, all the data from both the flight data recorder and the cockpit voice recorder had been downloaded.[2]:20[186] The data was analysed over the following weeks, and the findings published in the third interim report at the end of July.[187] The entire download was filmed and recorded.[187]

Between 5 May and 3 June 2011, 104 bodies were recovered from the wreckage, bringing the total number of bodies found to 154. Fifty bodies had been previously recovered from the sea.[141][188][189][190] The search ended with the remaining 74 bodies still not recovered.[191]

Investigation and safety improvements

The French authorities opened two investigations:

- A criminal investigation for manslaughter began on 5 June 2009, under the supervision of Investigating Magistrate Sylvie Zimmerman from the Paris Tribunal de Grande Instance.[192] The judge gave the investigation to the Gendarmerie nationale, which would conduct it through its aerial transportation division (Gendarmerie des transports aériens or GTA) and its forensic research institute (the "Institut de Recherche Criminelle de la Gendarmerie Nationale", FR).[193] As part of the criminal investigation, the DGSE (the external French intelligence agency) examined the names of passengers on board for any possible links to terrorist groups.[194] In March 2011, a French judge filed preliminary manslaughter charges against Air France and Airbus over the crash.[195]

- A technical investigation was started, the goal of which was to enhance the safety of future flights. In accordance with the provisions of ICAO Annex 13, the BEA participated in the investigation as representative for the state (country) of manufacture of the Airbus.[196] The Brazilian Air Force's Aeronautical Accidents Investigation and Prevention Center (CENIPA), the German Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accident Investigation (BFU), the Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB), and the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) also became involved in accordance with these provisions; the NTSB became involved as the state of manufacture of the General Electric equipment installed in the plane, and the other representatives could supply important information. The People's Republic of China, Croatia, Hungary, Republic of Ireland, Italy, Lebanon, Morocco, Norway, South Korea, Russia, South Africa, and Switzerland appointed observers, since citizens of those countries were on board.[197]

On 5 June 2009, the BEA cautioned against premature speculation as to the cause of the crash. At that time, the investigation had established only two facts - the weather near the aircraft's planned route included significant convective cells typical of the equatorial regions, and the speeds measured by the three pitot tubes differed from each other during the last few minutes of the flight.[198]

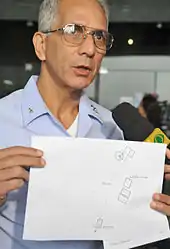

On 2 July 2009, the BEA released an intermediate report, which described all known facts, and a summary of the visual examination of the rudder and the other parts of the aircraft that had been recovered at that time.[1] According to the BEA, this examination showed:

- The airliner was likely to have struck the surface of the sea in a normal flight attitude, with a high rate of descent;[lower-alpha 8][1][199]

- No signs of any fires or explosions were found.

- The airliner did not break up in flight. The report also stresses that the BEA had not had access to the post mortem reports at the time of its writing.[1][200]

On 16 May 2011, Le Figaro reported that the BEA investigators had ruled out an aircraft malfunction as the cause of the crash, according to preliminary information extracted from the FDR.[201] The following day, the BEA issued a press release explicitly describing the Le Figaro report as a "sensationalist publication of non-validated information". The BEA stated that no conclusions had been made, investigations were continuing, and no interim report was expected before the summer.[202] On 18 May, the head of the investigation further stated no major malfunction of the aircraft had been found so far in the data from the flight data recorder, but that minor malfunctions had not been ruled out.[203]

Airspeed inconsistency

In the minutes before its disappearance, the aircraft's onboard systems sent a number of messages, via the ACARS, indicating disagreement in the indicated airspeed readings. A spokesperson for the BEA claimed, "the airspeed of the aircraft was unclear" to the pilots[143] and, on 4 June 2009, Airbus issued an Accident Information Telex to operators of all its aircraft reminding pilots of the recommended abnormal and emergency procedures to be taken in the case of unreliable airspeed indication.[204] French Transport Minister Dominique Bussereau said, "Obviously, the pilots [of Flight 447] did not have the [correct] speed showing, which can lead to two bad consequences for the life of the aircraft: under-speed, which can lead to a stall, and over-speed, which can lead to the aircraft breaking up because it is approaching the speed of sound and the structure of the plane is not made for enduring such speeds".[205]

Pitot tubes

Between May 2008 and March 2009, nine incidents involving the temporary loss of airspeed indication appeared in the air safety reports (ASRs) for Air France's A330/A340 fleet. All occurred in cruise between flight levels FL310 and FL380. Further, after the Flight 447 accident, Air France identified six additional incidents that had not been reported on ASRs. These were intended for maintenance aircraft technical logs drawn up by the pilots to describe these incidents only partially, to indicate the characteristic symptoms of the incidents associated with unreliable airspeed readings.[2]:122[206] The problems primarily occurred in 2007 on the A320, but awaiting a recommendation from Airbus, Air France delayed installing new pitot tubes on A330/A340 and increased inspection frequencies in these aircraft.[207][208]

When it was introduced in 1994, the Airbus A330 was equipped with pitot tubes, part number 0851GR, manufactured by Goodrich Sensors and Integrated Systems. A 2001 Airworthiness Directive (AD) required these to be replaced with either a later Goodrich design, part number 0851HL, or with pitot tubes made by Thales, part number C16195AA.[209] Air France chose to equip its fleet with the Thales pitot tubes. In September 2007, Airbus recommended that Thales C16195AA pitot tubes should be replaced by Thales model C16195BA to address the problem of water ingress that had been observed.[210] Since it was not an AD, the guidelines allow the operator to apply the recommendations at its discretion. Air France implemented the change on its A320 fleet, where the incidents of water ingress were observed and decided to do so in its A330/340 fleet only when failures started to occur in May 2008.[211][212]

After discussing these issues with the manufacturer, Air France sought a means of reducing these incidents, and Airbus indicated that the new pitot probe designed for the A320 was not designed to prevent cruise-level ice-over. In 2009, tests suggested that the new probe could improve its reliability, prompting Air France to accelerate the replacement program,[212] which started on 29 May. F-GZCP was scheduled to have its pitot tubes replaced as soon as it returned to Paris.[213] By 17 June 2009, Air France had replaced all pitot probes on its A330 type aircraft.[214]

In July 2009, Airbus issued new advice to A330 and A340 operators to exchange Thales pitot tubes for tubes from Goodrich.[215][216][217]

On 12 August 2009, Airbus issued three mandatory service bulletins, requiring that all A330 and A340 aircraft be fitted with two Goodrich 0851HL pitot tubes and one Thales model C16195BA pitot (or, alternatively, three of the Goodrich pitot tubes); Thales model C16195AA pitot tubes were no longer to be used.[218][2]:216 This requirement was incorporated into ADs issued by the European Aviation Safety Agency on 31 August[218] and by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) on 3 September.[219] The replacement was to be completed by 7 January 2010. According to the FAA, in its Federal Register publication, use of the Thales model has resulted in "reports of airspeed indication discrepancies while flying at high altitudes in inclement weather conditions" that "could result in reduced control of the airplane." The FAA further stated that the Thales model probe "has not yet demonstrated the same level of robustness to withstand high-altitude ice crystals as Goodrich pitot probes P/N 0851HL."

On 20 December 2010, Airbus issued a warning to roughly 100 operators of A330, A340-200, and A340-300 aircraft regarding pitot tubes, advising pilots not to re-engage the autopilot following failure of the airspeed indicators.[220][221][222] Safety recommendations issued by BEA for pitot probes design, recommended, "they must be fitted with a heating system designed to prevent any malfunctioning due to icing. Appropriate means must be provided (visual warning directly visible to the crew) to inform the crew of any nonfunctioning of the heating system".[2]:137

Findings from the flight data recorder

On 27 May 2011, the BEA released an update on its investigation describing the history of the flight as recorded by the FDR. This confirmed what had previously been concluded from post mortem examination of the bodies and debris recovered from the ocean surface; the aircraft had not broken up at altitude, but had fallen into the ocean intact.[223][200] The FDRs also revealed that the aircraft's descent into the sea was not due to mechanical failure or the aircraft being overwhelmed by the weather, but because the flight crew had raised the aircraft's nose, reducing its speed until it entered an aerodynamic stall.[76][224]

While the inconsistent airspeed data caused the disengagement of the autopilot, the reason the pilots lost control of the aircraft remains something of a mystery, in particular because pilots would normally try to lower the nose in the event of a stall.[225][226][227] Multiple sensors provide the pitch (attitude) information and no indication was given that any of them were malfunctioning.[228] One factor may be that since the A330 does not normally accept control inputs that would cause a stall, the pilots were unaware that a stall could happen when the aircraft switched to an alternate mode due to failure of the airspeed indication.[224][lower-alpha 9]

In October 2011, a transcript of the CVR was leaked and published in the book Erreurs de Pilotage (Pilot Errors) by Jean Pierre Otelli.[233] The BEA and Air France both condemned the release of this information, with Air France calling it "sensationalized and unverifiable information" that "impairs the memory of the crew and passengers who lost their lives."[234] The BEA subsequently released its final report on the accident, and Appendix 1 contained an official CVR transcript that did not include groups of words deemed to have no bearing on flight.[72]

Third interim report

On 29 July 2011, the BEA released a third interim report on safety issues it found in the wake of the crash.[3] It was accompanied by two shorter documents summarizing the interim report[235] and addressing safety recommendations.[236]

The third interim report stated that some new facts had been established. In particular:

- The pilots had not applied the unreliable-airspeed procedure.

- The pilot-in-control pulled back on the stick, thus increasing the angle of attack and causing the aircraft to climb rapidly.

- The pilots apparently did not notice that the aircraft had reached its maximum permissible altitude.

- The pilots did not read out the available data (vertical velocity, altitude, etc.).

- The stall warning sounded continuously for 54 seconds.

- The pilots did not comment on the stall warnings and apparently did not realize that the aircraft was stalled.

- There was some buffeting associated with the stall.

- The stall warning deactivates by design when the angle of attack measurements are considered invalid, and this is the case when the airspeed drops below a certain limit.

- In consequence, the stall warning came on whenever the pilot pushed forward on the stick and then stopped when he pulled back; this happened several times during the stall and this may have confused the pilots.

- Despite the fact that they were aware that altitude was declining rapidly, the pilots were unable to determine which instruments to trust; all values may have appeared to them to be incoherent.[3]

The BEA assembled a human factors working group to analyze the crew's actions and reactions during the final stages of the flight.[237]

A brief bulletin by Air France indicated, "the misleading stopping and starting of the stall-warning alarm, contradicting the actual state of the aircraft, greatly contributed to the crew's difficulty in analyzing the situation."[238][239]

Final report

On 5 July 2012, the BEA released its final report on the accident. This confirmed the findings of the preliminary reports and provided additional details and recommendations to improve safety. According to the final report,[2] the accident resulted from this succession of major events:

- Temporary inconsistency between the measured speeds, likely as a result of the obstruction of the pitot tubes by ice crystals, caused autopilot disconnection and reconfiguration to alternate law.

- The crew made inappropriate control inputs that destabilized the flight path.

- The crew failed to follow appropriate procedure for loss of displayed airspeed information.

- The crew were late in identifying and correcting the deviation from the flight path.

- The crew lacked understanding of the approach to stall.

- The crew failed to recognize the aircraft had stalled, and consequently did not make inputs that would have made recovering from the stall possible.[2]:200

These events resulted from these major factors in combination:[2]

- Feedback mechanisms between all those involved (the report identifies manufacturers, operators, flight crews, and regulatory agencies), which made it impossible to identify repeated non-application of the loss of airspeed information procedure, and to ensure that crews were trained in icing of the pitot probes and its consequences.

- The crew lacked practical training in manually handling the aircraft both at high altitude and in the event of anomalies of speed indication.

- The two co-pilots' task sharing was weakened both by incomprehension of the situation at the time of autopilot disconnection, and by poor management of the "startle effect", leaving them in an emotionally charged situation;

- The cockpit lacked a clear display of the inconsistencies in airspeed readings identified by the flight computers.

- The crew did not respond to the stall warning, whether due to a failure to identify the aural warning, to the transience of the stall warnings that could have been considered spurious, to the absence of any visual information that could confirm that the aircraft was approaching stall after losing the characteristic speeds, to confusing stall-related buffet for overspeed-related buffet, to the indications by the flight director that might have confirmed the crew's mistaken view of their actions, or to difficulty in identifying and understanding the implications of the switch to alternate law, which does not protect the angle of attack.

Independent analyses

Before and after the publication of the final report by the BEA in July 2012, many independent analyses and expert opinions were published in the media about the cause of the accident.

Significance of the accident

In May 2011, Wil S. Hylton of The New York Times commented that the crash "was easy to bend into myth" because "no other passenger jet in modern history had disappeared so completely—without a Mayday call or a witness or even a trace on radar." Hylton explained that the A330 "was considered to be among the safest" of the passenger aircraft. Hylton added that when "Flight 447 seemed to disappear from the sky, it was tempting to deliver a tidy narrative about the hubris of building a self-flying aircraft, Icarus falling from the sky. Or maybe Flight 447 was the Titanic, an uncrashable ship at the bottom of the sea."[188] Dr. Guy Gratton, an aviation expert from the Flight Safety Laboratory at Brunel University, said, "This is an air accident the likes of which we haven't seen before. Half the accident investigators in the Western world – and in Russia too – are waiting for these results. This has been the biggest investigation since Lockerbie. Put bluntly, big passenger planes do not just fall out of the sky."[240]

Angle-of-attack indication

In a July 2011 article in Aviation Week, Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger was quoted as saying the crash was a "seminal accident" and suggested that pilots would be able to better handle upsets of this type if they had an indication of the wing's angle of attack (AoA).[241] By contrast, aviation author Captain Bill Palmer has expressed doubts that an AoA indicator would have saved AF447, writing: "as the PF [pilot flying] seemed to be ignoring the more fundamental indicators of pitch and attitude, along with numerous stall warnings, one could question what difference a rarely used AoA gauge would have made".[242]

Following its investigation, the BEA recommended that the European Aviation Safety Agency and the FAA should consider making an AoA indicator on the instrument panel mandatory.[243] In 2014, the FAA streamlined requirements for AoA indicators for general aviation[244][245] without affecting requirements for commercial aviation.

Human factors and computer interaction

On 6 December 2011, Popular Mechanics published an English translation of the analysis of the transcript of the CVR controversially leaked in the book Erreurs de Pilotage.[233] It highlighted the role of the co-pilot in stalling the aircraft, while the flight computer was under alternate law at high altitude. This "simple but persistent" human error was given as the most direct cause of this accident.[224] In the commentary accompanying the article, they also noted that the failure to follow principles of crew resource management was a contributory factor.

The final BEA report points to the human-computer interface (HCI) of the Airbus as a possible factor contributing to the crash. It provides an explanation for most of the pitch-up inputs by the pilot flying, left unexplained in the Popular Mechanics piece: namely that the flight director display was misleading.[246] The pitch-up input at the beginning of the fatal sequence of events appears to be the consequence of an altimeter error. The investigators also pointed to the lack of a clear display of the airspeed inconsistencies, though the computers had identified them. Some systems generated failure messages only about the consequences, but never mentioned the origin of the problem. The investigators recommended a blocked pitot tube should be clearly indicated as such to the crew on the flight displays. The Daily Telegraph pointed out the absence of AoA information, which is so important in identifying and preventing a stall.[247] The paper stated, "though angle of attack readings are sent to onboard computers, there are no displays in modern jets to convey this critical information to the crews". Der Spiegel indicated the difficulty the pilots faced in diagnosing the problem: "One alarm after another lit up the cockpit monitors. One after another, the autopilot, the automatic engine control system, and the flight computers shut themselves off."[248] Against this backdrop of confusing information, difficulty with aural cognition (due to heavy buffeting from the storm, as well as the stall) and zero external visibility, the pilots had less than three minutes to identify the problem and take corrective action. The Der Spiegel report asserts that such a crash "could happen again".

In an article in Vanity Fair, William Langewiesche noted that once the AoA was so extreme, the system rejected the data as invalid, and temporarily stopped the stall warnings, but "this led to a perverse reversal that lasted nearly to the impact; each time Bonin happened to lower the nose, rendering the angle of attack marginally less severe, the stall warning sounded again—a negative reinforcement that may have locked him into his pattern of pitching up", which increased the angle of attack and thus aggravated the stall.[29]

Side-stick control issue

In April 2012 in The Daily Telegraph, British journalist Nick Ross published a comparison of Airbus and Boeing flight controls; unlike the control yoke used on Boeing flight decks, the Airbus side-stick controls give little visual feedback and no sensory or tactile feedback to the second pilot. The cockpit synthetic voice, however, does give an aural message 'Dual Input' whenever opposite inputs are initiated by the pilots.[235] Ross reasoned that this might in part explain why the PF's [pilot flying] fatal nose-up inputs were not countermanded by his two colleagues.[247][249] In fact BEA's final report July 2012 page 177 said, "during this forty-six second period between the autopilot disconnection and the STALL 2 warning, the C-chord warning (an altitude related alarm) sounded for a total duration of thirty-four seconds, thirty-one seconds of which as a continuous alert, and the STALL warning sounded for two seconds. The C-chord alert therefore saturated the aural environment within the cockpit... ...This aural environment certainly played a role in altering the crew’s response to the situation."[250]

In a July 2012 CBS report, Sullenberger suggested the design of the Airbus cockpit might have been a factor in the accident. The flight controls are not mechanically linked between the two pilot seats, and Robert, the left-seat pilot who believed he had taken over control of the aircraft, was not aware that Bonin continued to hold the stick back, which overrode Robert's own control.[251][252][lower-alpha 10] BEA's final report July 2012 page 179 said, "In fact the situation, with a high workload and multiple visual prompts, corresponds to a threshold in terms of being able to take into account an unusual aural warning. In an aural environment that was already saturated by the C-chord warning... "[253]

Fatigue

Getting enough sleep is a constant challenge for pilots of long-haul flights.[254] Although the BEA could find no "objective" indications that the pilots of Flight 447 were suffering from fatigue,[2]:100[255] some exchanges recorded on the CVR, including a remark made by Captain Dubois that he had only slept an hour,[lower-alpha 11] could indicate the crew were not well rested before the flight.[256] The co-pilots had spent three nights in Rio de Janeiro, but the BEA was unable to retrieve data regarding their rest and could not determine their activities during the stopover.[2]:24[257][258]

Aftermath

Shortly after the crash, Air France changed the number of the regular Rio de Janeiro-Paris flight from AF447 to AF445.[259]

Six months later, on 30 November 2009, Air France Flight 445 operated by another Airbus A330-203 (registered F-GZCK) made a mayday call because of severe turbulence around the same area and at a similar time to when Flight 447 was lost. Because the pilots could not obtain immediate permission from air traffic controllers (ATCs) to descend to a less turbulent altitude, the mayday was to alert other aircraft in the vicinity that the flight had deviated from its allocated flight level. This is standard contingency procedure when changing altitude without direct ATC authorization. After 30 minutes of moderate-to-severe turbulence, the flight continued normally. The flight landed safely in Paris 6 hours and 40 minutes after the mayday call.[260][261]

Inaccurate airspeed indicators

Several cases have occurred where inaccurate airspeed information led to flight incidents on the A330 and A340. Two of those incidents involved pitot probes.[lower-alpha 12] In the first incident, an Air France A340-300 (F-GLZL) en route from Tokyo to Paris experienced an event at 31,000 feet (9,400 m), in which the airspeed was incorrectly reported and the autopilot automatically disengaged. Bad weather and obstructed drainage holes in all three pitot probes were subsequently found to be the cause.[262] In the second incident, an Air France A340-300 (F-GLZN) en route from Paris to New York encountered turbulence followed by the autoflight systems going offline, warnings over the accuracy of the reported airspeed, and 2 minutes of stall alerts.[262]

Another incident on TAM Flight 8091, from Miami to Rio de Janeiro on 21 May 2009, involving an A330-200, showed a sudden drop of outside air temperature, then loss of air data, the ADIRS, autopilot and autothrust.[263] The aircraft descended 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) before being manually recovered using backup instruments. The NTSB also examined a similar 23 June 2009 incident on a Northwest Airlines flight from Hong Kong to Tokyo,[263] concluding in both cases that the aircraft operating manual was sufficient to prevent a dangerous situation from occurring.[264]

Following the crash of Air France 447, other Airbus A330 operators studied their internal flight records to seek patterns. Delta Air Lines analyzed the data of Northwest Airlines flights that occurred before the two companies merged and found a dozen incidents in which at least one of an A330's pitot tubes had briefly stopped working when the aircraft was flying through the ITCZ, the same location where Air France 447 crashed.[265][266]

Legal cases

Air France and Airbus have been investigated for manslaughter since 2011, but in 2019, prosecutors recommended dropping the case against Airbus and charging Air France with manslaughter and negligence, concluding, "the airline was aware of technical problems with a key airspeed monitoring instrument on its planes but failed to train pilots to resolve them".[267] The case against Airbus was dropped on 22 July the same year.[268] The case against Air France was dropped in September 2019 when magistrates said, "there were not enough grounds to prosecute".[269] However in 2021, a public prosecutor in Paris requested to have Airbus and Air France tried in a court of law.[270]

In popular culture

A one-hour documentary entitled Lost: The Mystery of Flight 447 detailing an early independent hypothesis about the crash was produced by Darlow Smithson in 2010 for Nova and the BBC. Using the then-sparse publicly available evidence and information, and without data from the black boxes, a critical chain of events was postulated, employing the expertise of an expert pilot, an expert accident investigator, an aviation meteorologist, and an aircraft structural engineer.[271][272][273][274]

On 16 September 2012, Channel 4 in the UK presented Fatal Flight 447: Chaos in the Cockpit, which showed data from the black boxes including an in-depth re-enactment. It was produced by Minnow Films.[275]

The aviation-disaster documentary television series Mayday (also known as Air Crash Investigation and Air Emergency) produced an hour-long episode titled "Air France 447: Vanished", which aired on 15 April 2013 in Great Britain and 17 May 2013 in the U.S.[276]

An article about the crash by American author and pilot William Langewiesche, entitled "Should Airplanes Be Flying Themselves?", was published by Vanity Fair in October 2014.[29]

A 99% Invisible podcast episode about the flight, entitled "Children of the Magenta (Automation Paradox, pt. 1)", was released on 23 June 2015 as the first of a two-part story about automation.[277]

In November 2015, Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor David Mindell discussed the Air France Flight 447 tragedy in the opening segment of an EconTalk podcast dedicated to the ideas in Mindell's 2015 book Our Robots, Ourselves: Robotics and the Myths of Autonomy.[278] Mindell said the crash illustrated a "failed handoff", with insufficient warning, from the aircraft's autopilot to the human pilots.[279]

Charles Duhigg writes about Flight 447 extensively in his book Smarter Faster Better, particularly about the errors the pilots made due to cognitive tunneling.

See also

- Indonesia AirAsia Flight 8501, a 2014 fatal crash involving an Airbus A320 resulting from a high-altitude stall and pilots making opposite inputs with the aircraft's side-stick controls

- Colgan Air Flight 3407, a 2009 fatal crash resulting from improper response to a stall by the pilot

- Birgenair Flight 301, a 1996 fatal crash resulting from blocked pitot tubes. which led to a high-altitude stall

- Aeroperú Flight 603, a 1996 fatal crash caused by a blocked static port

- Northwest Airlines Flight 6231, a 1974 fatal crash caused by frozen pitot tubes

- XL Airways Germany Flight 888T, a 2008 fatal crash resulting from a stall that was caused by frozen angle-of-attack sensors

- Search for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, a massive search effort for a missing airliner and its passengers after its disappearance over the Indian Ocean

- List of aircraft accidents and incidents resulting in at least 50 fatalities

- Air France accidents and incidents

Notes

- AF is the IATA designator and AFR is the ICAO designator

- At the time of its disappearance, F-GZCP was using satellite communication, its position over the mid-Atlantic being too far from land-based receivers for VHF to be effective.

- On the map, page 13 the coordinates in BEA's first interim report[57] with the information on page 13) is referenced as the "last known position" (French: Dernière position connue, "last known position").

- More precisely: that after one of the three independent systems had been diagnosed as faulty and excluded from consideration, the two remaining systems disagreed.

- 850 from its Navy and 250 Air Force.

- The areas showing detailed bathymetry were mapped using multibeam bathymetric sonar. The areas showing very generalized bathymetry were mapped using high-density satellite altimetry.

- The Remora 6000 remotely operated vehicle was designed and constructed by Phoenix International Holdings, Inc. of Largo, Maryland, United States.

- The airliner was considered to be in a nearly level attitude, but with a high rate of descent when it collided with the surface of the ocean. That impact caused high deceleration and compression forces on the airliner, as shown by the deformations that were found in the recovered wreckage.

- Some reports have described this as a deep stall,[229] but this was a steady state conventional stall.[230] A deep stall is associated with an aircraft with a T-tail, but this aircraft does not have a T-tail.[231] The BEA described it as a "sustained stall".[232]

- There was a similar side-stick control issue in the Air Asia Flight 8501 accident.

- "I didn't sleep enough last night. One hour – it's not enough right now." "Cette nuit, j'ai pas assez dormi. Une heure, c'était pas assez tout à l'heure."

- For an explanation of how airspeed is measured, see air data reference.

Works cited

Official sources (in English)

- BEA (France) (2 July 2009), Interim report on the accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris (PDF), translated by BEA from French, Le Bourget: BEA Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety, ISBN 978-2-11-098704-4, OCLC 821207217, archived (PDF) from the original on 3 May 2011, retrieved 13 March 2017CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link)

- BEA (France) (30 November 2009), Interim Report n°2 on the accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris (PDF), translated by BEA from French, Le Bourget: BEA Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety, ISBN 978-2-11-098715-0, OCLC 827738411, archived (PDF) from the original on 3 May 2011, retrieved 12 March 2017

- BEA (France) (29 July 2011), Interim report n °3 on the accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris. (PDF), translated by BEA from French, Le Bourget: BEA Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety, OCLC 827738487, archived (PDF) from the original on 19 September 2011, retrieved 12 March 2017

- BEA (France) (July 2012), Final report On the accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris (PDF), translated by BEA from French, Le Bourget: BEA Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety, archived (PDF) from the original on 11 July 2012, retrieved 12 March 2017

- BEA (France) (July 2012), "Appendix 1 CVR Transcript" (PDF), Final report On the accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris, translated by BEA from French, Le Bourget: BEA Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety, archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013, retrieved 11 July 2012

- BEA (France) (July 2012), "Appendix 2 FDR Chronology" (PDF), Final report On the accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris (PDF), translated by BEA from French, Le Bourget: BEA Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety, archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013, retrieved 12 March 2017

Official sources (in French) – the French version is the report of record.

- BEA (France) (2 July 2009), Accident survenu le 1er juin 2009 à l'Airbus A330-203 immatriculé F-GZCP exploité par Air France vol AF 447 Rio de Janeiro-Paris f-cp090601e : Rapport d'étape [Interim report on the accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris] (PDF) (in French), Le Bourget: BEA Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety, ISBN 978-2-11-098702-0, OCLC 816349880, archived (PDF) from the original on 31 May 2011, retrieved 13 March 2017

- BEA (France) (30 November 2009), Accident survenu le 1er juin 2009 à l'avion Airbus A330-203 immatriculé F-GZCP exploité par Air France Vol AF 447 Rio de Janeiro-Paris : rapport d'étape n° 2 [Interim Report n°2 on the accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris] (PDF) (in French), Le Bourget: BEA Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety, ISBN 978-2-11-098713-6, OCLC 762531678, archived (PDF) from the original on 31 May 2011, retrieved 13 March 2017

- BEA (France) (29 July 2011), Accident survenu le 1er juin 2009 à l'avion Airbus A330-203 immatriculé F-GZCP exploité par Air France Vol AF 447 Rio de Janeiro-Paris : rapport d'étape n° 3 [Interim Report n°3 on the accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris] (PDF) (in French), Le Bourget: BEA Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety, archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2011, retrieved 13 March 2017

- BEA (France) (July 2012), Accident survenu le 1er juin 2009 à l'Airbus A330-203 immatriculé F-GZCP exploité par Air France vol AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris Rapport final [Final report On the accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris] (PDF) (in French), Le Bourget: BEA Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety, archived (PDF) from the original on 11 July 2012, retrieved 12 March 2017

- BEA (France) (July 2012), "Annexe 1 Transcription CVR" [Appendix 1 CVR Transcript] (PDF), Accident survenu le 1er juin 2009 à l'Airbus A330-203 immatriculé F-GZCP exploité par Air France vol AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris [Accident survenu le 1er juin 2009 à l’Airbus A330-203 immatriculé F-GZCP exploité par Air France vol AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris] (in French), Le Bourget: BEA Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety, archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2019, retrieved 24 July 2019

- BEA (France) (July 2012), "Annexe 2 Chronologie FDR" [Appendix 2 FDR Chronology] (PDF), Accident survenu le 1er juin 2009 à l'Airbus A330-203 immatriculé F-GZCP exploité par Air France vol AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris [Final report On the accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris] (in French), Le Bourget: BEA Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety, archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2019, retrieved 24 July 2019

Other sources

- Otelli, Jean-Pierre (13 October 2011). Erreurs de pilotage: Tome 5 [Pilot Error: Volume 5] (in French). Levallois-Perret: Altipresse. ISBN 979-10-90465-03-9. OCLC 780308849.

- Rapoport, Roger (2011). The Rio/Paris Crash: Air France 447. Lexographic Press. ISBN 978-0-9847142-0-9.

- Palmer, Bill (20 September 2013). Understanding Air France 447 (paperback). William Palmer. ISBN 9780989785723.

References

- BEA first 2009.

- BEA final 2012

- BEA third 2011.

- Clark, Nicola (29 July 2011). "Report on Air France Crash Points to Pilot Training Issues". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- Ranter, Harro. "Accident description F-GZCP". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- "F-GZCP Air France Airbus A330-203 – cn 660". Planespotters. 2014. Archived from the original on 5 May 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- "F-GZCP", Aviation civile [Civil aviation] (registration data) (in French), The Government of France, archived from the original on 20 July 2011, retrieved 27 June 2009

- "EASA Type Certificate Data Sheet for AIRBUS A330" (PDF). European Aviation Safety Agency. 22 November 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2014. p. 18 sec. 1.2.1

- "All Accident + Incidents 2006". Jet Airliner Crash Data Evaluation Centre. Archived from the original on 7 June 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "JACDEC Special accident report Air France Flight 447". Jet Airliner Crash Data Evaluation Centre. Archived from the original on 5 June 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- "Key figures in global battle against illegal arms trade lost in Air France crash". The Herald (Glasgow). 6 June 2009. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011.

- Byrne, Ciaran; Kane, Conor; Hickey, Shane; Bray, Allison (2 June 2009). "Three Irish doctors die in mystery jet tragedy". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "Zeisterse in verdwenen Air France vlucht" [Zeisterse in disappeared Air France flight]. RTV Utrecht (in Dutch). rtvutrecht.nl. 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 11 June 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- "Alexander kommer aldri tilbake på skolen" [Alexander never comes back to school]. Dagbladet (in Norwegian). 3 June 2009. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- "Violeta Bajenaru-Declerck, romanca aflata la bordul Air France 447" [Violeta Bajenaru-Declerck, Romanian on Air France 447]. Gândul (in Romanian). 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014.

- Gorelova, Maria; Bogdanova, Ekaterina (1 June 2009). "В пропавшем над Атлантикой самолете был россиянин Андрей Киселев" [The missing plane over the Atlantic was Russian Andrei Kiselev]. Komsomolskaya Pravda (in Russian). Izdatelsky Dom Komsomolskaya Pravda. Archived from the original on 5 June 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Truinová, Durina (3 June 2009). "Aj tretí Slovák zo strateného letu bol z Levického okresu" [The third Slovak from the lost flight was also from the Levice district]. SME (in Slovak). Petit Press. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Andrés Suárez Montes: Nueva vida en París" [Andrés Suárez Montes: New life in Paris]. ABC (Spain) (in Spanish). 4 August 2009. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- Thorsson, Eric. "Nya fynd kan lösa gåtan om deras död" [New findings may solve the mystery of their deaths]. Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 6 April 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- "Airbus disparu: témoignages, hypothèses et démenti" [Airbus disappeared: testimonies, hypotheses and denial]. rts.ch (in French). Radio Télévision Suisse. 9 June 2009. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "The Last Recital in Rio de Janeiro". Korhan Bircan. 6 June 2009. Archived from the original on 19 July 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- Moyer, Amanda (3 June 2009). "American couple on Flight 447 loved life, relatives say". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Press release N° 5" (Press release). Air France. 1 June 2009. Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- Naughton, Philippe; Bremner, Charles (1 June 2009). "Air France jet with 215 people on board 'drops off radar'". The Times. London. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- "Air France statement on crashed airliner in the Atlantic". BNO News. 1 June 2009. Archived from the original on 7 June 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- "French plane lost in ocean storm". BBC News. BBC. 1 June 2009. Archived from the original on 3 June 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

At 0530 GMT, Brazil's air force launched a search-and-rescue mission, sending out a coast guard patrol aircraft and a specialised air force rescue aircraft. ... France is despatching three search planes based in Dakar

- "Captain of Air France Flight 447 was son of pilot". Deseret News. Associated Press. 3 June 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Faccini, Barbara (January 2013). "Four minutes, 23 seconds – Flight AF447" (PDF). Volare Aviation Monthly. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Langewiesche, William; McCabe, Sean (October 2014). "The Human Factor". Vanity Fair. Photo Illustration. Archived from the original on 17 September 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- "Inhumés trois ans après le crash aérien" [Buried three years after the air crash]. SudOuest.fr (in French). Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Wise, Jeff (6 December 2011). "What Really Happened Aboard Air France 447". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "What Really Happened Aboard Air France 447" (PDF). hptinstitute.com. Human Performance Training Institute Inc. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "Pierre Cédric et Isabelle Bonin" [Pierre Cédric and Isabelle Bonin]. skyrock.com (in French). Skyrock. 18 June 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "Today may be all we have". harrisonjones. 22 October 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Inside cockpit Af447, retrieved 12 November 2019

- "Flight 447 pilot had 20 years of flying for Air France". Calvin Palmer's Weblog. 3 June 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "תג #af447 בטוויטר" [Tag #af447 on Twitter]. twitter.com (in Hebrew). Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "List of passengers aboard lost Air France flight". Huffington Post. USA. Associated Press. 4 June 2009.

- "Air France Update". Flight Air France 447 Rio de Janeiro – Paris-Charles de Gaulle. Air France. 5 October 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- "Ships head for area where airplane debris spotted". CNN. 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- Chrisafis, Angelique; Phillips, Tom (1 June 2009). "Terminal said 'delayed' but the faces betrayed the truth". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- McNeil Jr, Donald G.; Negroni, Christine (1 June 2009). "Search Is on for Wreckage of Missing Air France Jet". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Air France. 9 July 2009. Archived from the original on 6 October 2009.

Our first priority was to organize the arrival of 60 to 70 relatives at Roissy. There were not more than this because many passengers were connecting passengers.

- "Air France pays $24,500 to crash victims' families". CNN. 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 21 June 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- "Voo Air France 447: últimas informações" [Flight Air France 447: latest information]. Veja (in Portuguese). Brazil: Editora Abril. 1 June 2009. Archived from the original on 5 June 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- "Cotidiano – Família Orleans e Bragança confirma que príncipe brasileiro estava no voo AF 447" [Daily – Orleans and Braganza family confirms that Brazilian prince was on flight AF 447]. Folha on line (Brazil) (in Portuguese). Agência Brasil. 1 June 2009. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- "Belgisch-Braziliaanse prins onder de slachtoffers" [Belgian-Brazilian prince among the victims] (in Dutch). Standaard.be. 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 5 June 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- "Confira os nomes de 84 passageiros que estavam no voo AF 447" [Confirmation of names of 84 passengers at AF 447]. Correio Braziliense (in Portuguese). 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- TRENTO10 anni fa la tragedia dell’Air France che costò la vita a Giovanni Battista Lenzi, 31 May 2019

- "Airbus: apólice de US$94 mi e seguro incalculável" [Airbus: $94m policy and incalculable insurance] (in Portuguese). Sao Paulo: Monitor Mercantil. 1 June 2009. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- "Lista não oficial de vítimas do voo 447 da Air France inclui executivos, médicos e até um membro da família Orleans e Bragança" [Unofficial list of Air France flight 447 victims includes executives, doctors and even a member of the Orleans and Braganza family] (in Portuguese). Globo. 1 June 2009. Archived from the original on 14 June 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2009.