Agnes Weinrich

Agnes Weinrich (1873–1946) was one of the first American artists to make works of art that were modernist, abstract, and influenced by the Cubist style. She was also an energetic and effective proponent of modernist art in America, joining with like-minded others to promote experimentation as an alternative to the generally conservative art of their time.

Agnes Weinrich | |

|---|---|

Agnes Weinrich | |

| Born | Agnes Weinrich July 16, 1873 |

| Died | April 17, 1946 (aged 72) |

| Resting place | Trinity Cemetery, Mount Union, Iowa |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Art Students League, Art Institute of Chicago, and Charles Hawthorne in Provincetown |

| Known for | Modern art |

| Movement | Cubism, Abstract art |

Life and work

Early years

Agnes Weinrich was born in 1873 on a prosperous farm in south east Iowa. Both her father and mother were German immigrants and German was the language spoken at home. Following her mother's death in 1879 she was raised by her father, Christian Weinrich. In 1894, at the age of 59, he retired from farming and moved his household, including his three youngest children—Christian Jr. (24), Agnes (21), and Lena (17), to nearby Burlington, Iowa, where Agnes attended the Burlington Collegiate Institute from which she graduated in 1897.[1][2][3] Christian took Agnes and Lena with him on a trip to Germany in 1899 to reestablish links with their German relatives. When he returned home later that year, he left the two women in Berlin with some of these relatives, and when, soon after his return, he died, they inherited sufficient wealth to live independently for the rest of their lives.

Either before or during their trip to Germany Lena had decided to become a musician and while in Berlin studied piano at the Stern Conservatory. On her part, Agnes had determined to be an artist and began studies toward that end at the same time.[1][4] In 1904 the two returned from Berlin and settled for two years in Springfield, Illinois, where Lena taught piano in public schools and Agnes painted in a rented studio. At this time Lena changed her name to Helen. In 1905 they moved to Chicago where Agnes studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago under John Vanderpoel, Nellie Walker, and others.[1]

In 1909 Agnes and Helen returned to Berlin and traveled from there to Munich, where Agnes studied briefly under Julius Exter, and on to Rome, Florence, and Venice before returning to Chicago.[5] They traveled to Europe for the third, and last, time in 1913, spending a year in Paris. There, they made friends with American artists and musicians who had gathered there around the local art scene. Throughout this period, the work Agnes produced was skillful but unoriginal—drawings, etching, and paintings in the dominant academic and impressionist styles.[1]

On her return from Europe in 1914, she continued to study art, during the warm months of the year in Provincetown, Massachusetts,[1] where she was a member of the Provincetown Printers art colony in Massachusetts,[6] and during the colder ones in New York City. In Provincetown she attended classes at Charles Hawthorne's Cape Cod School of Art and in New York, the Art Students League.[1]

Hawthorne and other artists established the Provincetown Art Association in 1914 and held the first of many juried exhibitions the following year. Weinrich contributed nine pictures to this show, all of them representational and somewhat conservative in style.[1]

A pencil sketch made about 1915 shows a figure, probably one of the Portuguese women of Provincetown. Weinrich was a meticulous draftsperson and this drawing is typical of the work she did in the academic style between 1914 and 1920. She also produced works more akin to the Impressionist favored by Hawthorne and many of his students. When in 1917 Weinrich showed paintings in a New York women's club, the MacDowell Club, the art critic for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle said they showed a "strong note of impressionism."[7]

In 1916 Weinrich joined a group of printmakers which had begun using the white-line technique pioneered by Provincetown artist B.J.O. Nordfelt. She and the others in the group, including Blanche Lazzell, Ethel Mars and Edna Boies Hopkins, worked together, exchanging ideas and solving problems.[1][8] A year later Weinrich showed one of her first white-line prints at an exhibition held by the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia.[9]

Broken Fence, in its two states—the print and the woodblock from which she made it—show Weinrich to be moving away from realistic presentation, towards a style, which, while neither abstract, nor Cubist, brings the viewer's attention to the flat surface plane of the work with its juxtaposed shapes and blocks of contrasting colors.

When in 1920 the informal white-line printmakers' group organized its own exhibition, Weinrich showed a dozen works, including one called Cows Grazing in the Dunes near Provincetown. This print shows greater tendency to abstraction than eitherBroken Fence or the prints made by other Provincetown artists of the time. The cows and dunes are recognizable but not presented realistically. The white lines serve to emphasize the blocks of muted colors which are the print's main pictorial elements. Weinrich uses the texture of the wood surface to call attention to the two-dimensional plane—the paper on which she made the print—in contrast with the implicit depth of foreground and background of cows, dunes, and sky. While the work is not Cubist, it has a proto-Cubist feel in a way that is similar to some of the more abstract paintings of Paul Cézanne.[10]

By 1919 or 1920, while still spending winters in Manhattan and summers on Cape Cod, the sisters came to consider Provincetown their formal place of residence.[1][11][12][13] By that time they had also met the painter, Karl Knaths. Like themselves a Midwesterner of German origin who had grown up in a household where German was spoken, he settled in Provincetown in 1919. Agnes and Knaths shared artistic leanings and mutually influenced each other's increasing use of abstraction in their work.[1][14]

The sisters and Knaths became close companions. In 1922 Knaths married Helen and moved into the house which the sisters had rented. He was then 31, Helen 46, and Agnes 49 years old. When, two years later, the three decided to become year-round residents of Provincetown, Agnes and Helen used a part of their inheritance to buy land and materials for constructing a house and outbuildings for the three of them to share. Knaths himself acquired disused structures nearby as sources of lumber and, having once been employed as a set building for a theater company, he was able to build their new home.[15]

Weinrich was somewhat in advance of Knaths in adopting a modernist style. She had seen avant-garde art while in Paris and met American artists who had begun to appreciate it. On her return to the United States she continued to discuss new theories and techniques with artists in New York and Provincetown, some of whom she had met in Paris. This loosely-knit group influenced one another as their individual styles evolved. In addition to Blance Lazzell, already mentioned, the group included Maude Squires, William Zorach, Oliver Chaffee, and Ambrose Webster. Some of them, including Lazzell and Flora Schofield had studied with influential modernists in Paris and most had read and discussed the influential Cubist and Futurist writings of Albert Gleizes and Gino Severini.[16][17]

Mature style

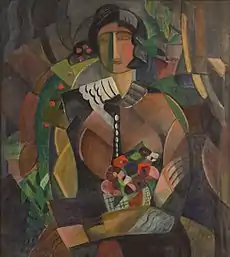

Two of Weinrich's paintings, both produced about 1920, mark the emergence of her mature style. The first, Woman With Flowers, is similar to one by the French artist, Jean Metzinger titled Le goûter (Tea Time) (1911).

Like much of Metzinger's work, Le goûter was discussed in books and journals of the time—including the book Du "Cubisme" co-authored by Metzinger and Albert Gleizes.[18] Because the group with which Weinrich associated read about and discussed avant-garde art in general and Cubism in particular, it is reasonably likely that Weinrich was familiar with Metzinger's work before she began her own.

The second painting, Red Houses, bears general similarity to landscapes by Cézanne and Braque. Both paintings are Cubist in style. However, with them Weinrich did not announce an abrupt conversion to Cubism, but rather marked a turning toward greater experimentation. In her later work she would not adopt a single style or stylistic tendency, but would produce both representative pictures and ones that were entirely abstract, always showing a strong sense of the two-dimensional plane of the picture's surface. After she made these two paintings neither her subject matter nor the media she used would dramatically change. She continued to employ subjects available to her in her Provincetown studio and the surrounding area to produce still lifes, village and pastoral scenes, portraits, and abstractions in oil on canvas and board; watercolor, pastel, crayon and graphite on paper; and woodblock prints.[19]

Possessing an outgoing and engaging personality and an active, vigorous approach to life, Weinrich promoted her own work while also helping Karl Knaths to develop relationships with potential patrons, gallery owners, and people responsible for organizing exhibitions. With him, she put herself in the forefront of an informal movement toward experimentation in American art. Since, because of her independent means, she was not constrained to make her living by selling art, she was free to use exhibitions and her many contacts with artists and collectors to advance appreciation and understanding of works which did not conform to the still-conservative norm of the 1920s and 1930s.[1][20][21]

Early in the 1920s, critics began to take notice of her work, recognizing her departure from the realism then prevailing in galleries and exhibitions. Paintings that she showed in 1922 drew the somewhat dry characterization of "individualistic.",[22] and in 1923 her work drew praise from a critic as "abstract, but at the same time not without emotion."[23]

In 1925 Weinrich became a founding member of the New York Society of Women Artists. Other Provincetown members included Blanche Lazzell, Ellen Ravenscroft, Lucy L'Engle, and Marguerite Zorach. The membership was limited to 30 painters and sculptors all of whom could participate in the group's exhibitions, each getting the same space.[22][24][25] The group provided a platform for their members to distinguish themselves from the genteel and traditionalist art that women artists were at that time expected to show[26] and, by the account of a few critics, it appears their exhibitions achieved this goal.[1][27][28][29]

In 1926 Weinrich joined with Knaths and other local artists in a rebellion against the "traditional" group that had dominated the Provincetown Art Association. For the next decade, 1927 through 1937, the association would mount two separate annual exhibitions, the one conservative in orientation and the other experimental, or, as it was said, radical.[30][31] Both Weinrich and Knaths participated on the jury that selected works for the first modernist exhibition.[11]

Weinrich's painting, Still Life, made about 1926, may have been shown in the 1927 show. Representative of some aspects of her mature style, it is modernist but does not show Cubist influence. The objects pictured are entirely recognizable, but treated abstractly. Although fore- and background are distinguishable, the objects, as colored forms, make an interesting and visually satisfying surface design.

In 1930 Weinrich put together a group show for modernists at the GRD Gallery in New York. The occasion was the first time a group of Provincetown artists exhibited together in New York. For it she selected works by Knaths, Charles Demuth, Oliver Chaffee, Margarite and William Zorach, Jack Tworkov, Janice Biala, Niles Spencer, E. Ambrose Webster, and others.[1][22]

Later years

Weinrich turned 60 on July 16, 1933. Although she had led a full and productive life devoted to development of her own art and to the advancement of modernism in art, she did not cease to work toward both objectives. She continued to work in oil on canvas and board, pastel and crayon on paper, and woodblock printing. Her output continued to vary in subject matter and treatment. For example, Still Life with Leaves, circa 1930 (oil on canvas, 18 x 24 inches) contains panels of contrasting colors with outlining similar to Knaths's style. Movement in C Minor, circa 1932 (oil on board, 9 x 12 inches) is entirely abstract. It too relates to Knaths's work, both in treatment (again, outlined panels of contrasting colors) and in its apparent relationship to music, something in which Knaths was also interested. Fish Shacks, circa 1936 (monochrome woodblock print) is severely abstract and has a strong Cubist feel. Untitled Abstraction, circa 1938 (oil on canvasboard, 12.25 x 12 inches) is very different from the abstract work of the earlier 1930s. It is a geometric abstraction showing influence of Wassily Kandinsky[32] consisting of rectilinear color panels in cool tones with to contrasting panels in ochre and red. Floral Still Life, circa 1940 (Crayon on paper, 7 x 9.5 inches) contains a frame within a frame, emphasizing the surface plane dramatically, and is also entirely abstract. Its composition consists of star-like shapes in blue and magenta in a lively pattern against a dark, textured background.

Critical reception

Despite the quality of her work and despite the energy and skill with which she worked both to develop her own talent and to further the progressive movement in American art, Weinrich received little recognition during her lifetime and has not received much more since her death. Most accounts of her life and work repeat a few salient facts. They do not provide citations and some of their claims cannot be confirmed.[33][34] Only one person, Louise R. Noun, studied her in detail. See the exhibition catalog she co-wrote and the article by her, both cited in the "Further reading" section below.

There is no evidence that Weinrich was ever represented by a commercial gallery and it is likely that she made her sales via exhibitions and out of her studio. She did not usually provide date, name, place, or subject on her works and kept few records of what she produced. For these reasons, and because (a) they were not inventoried by art dealers in her lifetime and (b) she made a lot of art that was not sold, there is often doubt about the provenance of any given piece.

Exhibitions

This is a selective list of exhibitions in which she participated during her life. Its main source is Louise Noun's article on Weinrich in Woman's Art Journal,[1] supplemented by contemporary news accounts in The New York Times, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, the New York Evening Post, The Philadelphia Inquirer, and The Christian Science Monitor.

- 1915 onward: Provincetown Art Association

- 1917: Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts

- 1917: Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia

- 1917-23: Society of Independent Artists, New York

- 1919: Art Institute of Chicago

- 1920: Boston Arts Club

- 1926 onward: New York Society of Women Artists

- 1928: Grace Horn Gallery, Boston

- 1929: Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia

- 1932: Boston Public Library

- 1936: Harley Perkins Gallery, Boston (solo)

- 1938: Boston Society of Independent Artists

- 1938: Washington Public Library, Washington, D.C.

- 1939: Corcoran Gallery Biennial, Washington, D.C.

- 1939: Fogg Art Museum Twentieth Century Club, Boston

- 1939: Witherstine Gallery, Boston

- 1939: Institute of Modern Art, Boston

- 1945: Woljeska Gallery, Brooklyn, New York

References

Notes

- Noun, Louise R. (Autumn 1995 – Winter 1996). "Agnes Weinrich". Woman's Art Journal. 16 (2): 10–15. doi:10.2307/1358569. JSTOR 1358569.

- "Agnes Weinrich in household of Christian Weinrich, 'United States Census, 1880'". United States Census, 1880, Christian Weinrich, Washington, Des Moines, Iowa, United States; citing sheet 2C, NARA microfilm publication T9. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

- No Reins (2007). "Christian Weinrich (1834 - 1899)". Find A Grave Memorial 22124423. Retrieved 2014-06-23.

- "Early Provincetown Artist: Agnes Weinrich". Julie Heller Gallery, Provincetown, Massachusetts. Archived from the original on 2014-07-17. Retrieved 2014-06-20.

- "Miss Agnes Weinrich". New York, Passenger Arrival Lists (Ellis Island), 1892-1924 — FamilySearch.org citing National Archives, Washington D.C. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

Miss Agnes Weinrich of Chicago, Ill., arrived at New York from Genoa, 11 May 1910, on the Princess Irene

- "Provincetown Printers/A Woodcut Tradition". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- "In the World of Art". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. New York, NY. 1917-10-21.

Agnes Weinrich shows a strong note of impressionism in "Two Girls," "A House in Provincetown," "Village Street," and several landscapes.

- "Free art workshop at Topsfield Library June 7 - News - Tri-Town Transcript - Boxford, MA". boxford.wickedlocal.com. Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- Philadelphia Water Color Club (1917). Annual Water Color and Miniature Exhibitions Catalogue. p. 46.

- "Agnes Weinrich". ifpda.org. Archived from the original on 2015-01-12. Retrieved 2014-06-24.

- Bakker, James R. (2011). "Charles Webster Hawthorne Founds the Cape Cod School of Art". Tides of Provincetown, reproduced from the New Britain Museum of American Art. Archived from the original on 2015-01-13. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

- Iowa Artists of the First Hundred Years. Wallace-Homestead Company. 1939.

- "Agnes WEINRICH's biography". artprice.com. Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- "Contemporary and Early Provincetown Art: Agnes Weinrich (1873-1946)". Gallery Ehva. Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- Benson, Gertrude (1952-04-30). "Karl Knaths Hails Order in Art Works" (PDF). The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 24. Retrieved 2014-05-28.

- Del Deo, Josephine C. (2011). "Ross Moffett and the Modernist Tradition". Tides of Provincetown, reproduced from the New Britain Museum of American Art. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

- Charles Edward Eaton (2001). The Man from Buena Vista: Selected Nonfiction, 1944-2000. Associated University Presses. pp. 108–32. ISBN 978-0-8453-4878-9.

- Albert Gleizes; Jean Metzinger (1913). Cubism. T.F. Unwin.

- Society of Independent Artists (1921). 1921 Catalogue OF THE Fifth Annual Exhibition OF The Society of Independent Artists; No Jury No Prizes. Society of Independent Artists. Retrieved 2014-05-27.

- "Announcements (Art)". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. New York, NY. 1930-03-30.

The New York Society of Women Artists is holding its fifth annual show from March 30 to April 12 in the first floor galleries of the Art Center, 65 E 55th St. The main object of the New York Society of Women Artists is to have an annual exhibition which gives its members an opportunity to show a group of their work, which is representative of the more progressive tendencies in art.

- "Other Art Events". New York Evening Post. New York, NY. 1932-02-06.

At the gallery of the New York Society of Women Painters and Sculptors in the Squibb Building a contrast is afforded in the exhibition of paintings by Margaret Huntington and of paintings and drawings by Agnes Weinrich. Miss Huntington's ... make a foil for the abstract decorative pattern of Miss Weinrich's paintings executed in low, muted tones. The work of both artists never appeared in so much advantage as in this daylight-flooded gallery. However, so many of these excellent works should not be in possession of either painter—this is intended as a rebuke to the unappreciative, non-buying public, not to the artists.

- "William and Lucy L'Engle | D. Wigmore Fine Art". dwigmore.com. 2013. Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- "Art; Current Exhibitions; Current Notes; Modern Paintings". The New York Times. New York, NY. 1923-03-11.

- "Women Artists Form a New Group". The New York Times. New York, NY. 1925-05-03.

- "Notes and Activities in the World of Art". New York Sun. New York, NY. 1926-02-27.

- Ross Moffett (1964). Art in narrow streets: the first thirty-three years of the Provincetown Art Association. Kendall Print. Co.

- Read, Helen Appleton (1926-04-25). "Women's Art Not Necessarily Feminine, New Group Demonstrates". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. New York, NY.

The present exhibition asks no quarter on the grounds of sex; does not count on the gallant half patronizing attitude with which the world still regards women's art.... [this is] a group of painters and sculptors who think for themselves and so have something to say. They are not looking at nature through art as it has been seen by some one else, so frequently the case with women's pictures, but are recording personal reactions to life.

- Breuning, Margaret (1926-04-24). "About Artists and Their Work". The New York Evening Post. New York, NY.

Woman [as artist] has not had a very long period of unclipped wings in which to practice flying, but even so she is making good progress in her flight to the stars, where, after all, many of her patronizing critics have not yet arrived either.... At the Anderson Galleries a breath of freshness and vitality seems to blow through the gallery.

- McCarroll, Marion Clyde (1929-02-25). "New York Society of Women Artists Opens Exhibit of Painting and Sculpture at Anderson Galleries". The New York Evening Post. New York, NY.

The New York Society of Women Artists [gives those attending its exhibitions an] opportunity for a more widespread knowledge of what women artists are doing along modern lines.... Women who are interested in experimenting with new artistic forms find stimulus in association with those of similar interests.... [Artists today have been relieved of the] repression to which women were so long subjected.... In times past the announcement of an art exhibition of women only was practically an admission of defeat, an indication that they were unable to obtain attention otherwise. Today, it is an occasion which draws every one interested in art.

- "History | Provincetown Art Association and Museum". Retrieved 2014-06-26.

True to its mission, the organization represented both sides of the artistic argument, mounting separate "Modern" and "Regular" summer exhibitions between 1927 and 1937. Still, the conciliation reached in 1937 was only partial; instead of separate exhibitions, separate juries installed concurrent exhibitions on opposite gallery walls, with a coin-flip deciding that the modernists’ work hung on the left.

- McCarthy, Christine (2011). "The Provincetown Art Association and Museum". Tides of Provincetown, reproduced from the New Britain Museum of American Art. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

- See, for example, his Three Rectangles of 1930

- Noun, Louise R. (Autumn 1995 – Winter 1996). "Agnes Weinrich". Woman's Art Journal. 16 (2): 10–15. doi:10.2307/1358569. JSTOR 1358569.

Although several chroniclers of Weinrich's life claim she studied with Gleizes and other Modernists in Paris, there is no evidence to support this statement. According to Knaths, "It was not until she came to Provincetown in 1914 that she was influenced by the modern movement."... Some chroniclers of Agnes's life claimed the Armory Show made a "deep and lasting impression" on her, but I believe she was probably in Europe during the exhibit's 1913 run in New York and Chicago. She most likely was familiar with much of the work exhibited because of her extended sojourns abroad. See Jules Heller and Nancy G. Heller, North American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century (New York: Garland, 1995), 570.

- The short biographic summaries given by art auction houses where her work is listed vary little, provide no evidence, and have the weaknesses which Louise R. Noun points out.

Other sources

- "An Art Exhibition Without a Jury System of Award". The New York Times. New York, NY. 1911-05-14.

- Norton, Esther (1926-04-24). "New York Society of Women Artists, Year Old Organization, Is Now Exhibiting Work of Members for First Time". The New York Sun. New York, NY.

- "Women Artists Open Exhibit at Newport in July". The New York Sun. New York, NY. 1930-06-30.

This colony is to have one of the important art shows of the summer. It is to be that of the painters and sculptors of the New York Society of Women Artists in conjunction with the Art Association of Newport, from July12 to August 2 in the Cushing Memorial Hall.

- "New York Society of Women Artists' Exhibit". The New York Evening Post. New York, NY. 1935.

Agnes Weinrich continues her building up of pattern with color planes, especially effective in "Leaves."

- Ronald A. Kuchta (1977). Provincetown Painters, 1890s-1970s. Visual Artis Publications. p. 31.

- Forman, Deborah. "Hans Hofmann in Provincetown". Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Inc. Retrieved 2014-06-23.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) (1994). American Impressionism and Realism: The Painting of Modern Life, 1885-1915. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 351. ISBN 978-0-87099-700-6.

- "Agnes Weinrich". Otto K Knaths, Provincetown, Barnstable, Massachusetts, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 0015, sheet 1A, family 1, NARA microfilm publication T626, roll 883. familysearch.org. Retrieved 2014-05-24.

- Gernand, John. "Oral history interview with John Gernand, 1979 Jan. 18-Feb. 14". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- "Agnes Weinrich". Otto K Knaths, Provincetown Town, Barnstable, Massachusetts, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 1-39, sheet 1A, family 8, NARA digital publication of T627, roll 1566. familysearch.org. Retrieved 2014-05-24.

- Gates, Mo and Dave (2012). "Agnes Weinrich (1875 - 1946)". - Find A Grave Memorial 84105707. Retrieved 2014-06-20.

- No Reins (2007). "Christian Weinrich (1834 - 1899)". Find A Grave Memorial 22124423. Retrieved 2014-06-23.

- "8 Commercial Street; Building Provincetown; The History of Provincetown Told Through Its Built Environment". buildingprovincetown.wordpress.com. 2010. Retrieved 2014-06-20.

- Rose, Jean Block (ed.). Exhibition Catalog: The Eye of the Collector: The Jewish Vision of Sigmund R. Balka, September 19, 2006 - January 30, 2007. New York: Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion Museum. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

- "Artist dies at age 78". The Hawk-Eye. Burlington, Iowa: Quoted in: Message Board, IAGenWeb Project, Karl Knaths nd - 1971 KNATHS, WEINRICH, WITTE, PECKHAM, EWINGER, DUTTON, VOLLMER, PRUGH, SCHRAMM, Posted By: deb, Date: 3/2/2008 at 15:31:56. 2008-03-02. Retrieved 2014-05-24.

- Gates, Mo & Dave (2012). "Otto 'Karl' Knaths (1892 - 1971) - Find A Grave Memorial". Find A Grave Memorial # 84106557. Retrieved 2014-05-24.

maintained by GraveTracker

- No Reins (2008). "Helen Lena Weinrich Knaths (1876 - 1978) - Find A Grave Memorial". Find A Grave Memorial # 24892240. Retrieved 2014-05-24.

Maintained by GraveTracker

- "Karl Knaths (1891-1971) Biography". American Art @ The Phillips Collection. Retrieved 2014-05-24.

Adapted from Eye, LBW

- "Helen W. Knaths and Agnes Weinrich Trust". National Center for Charitable Statistics. Archived from the original on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- "The Tides of Provincetown: Pivotal Years in America's Oldest Continuous Art Colony (1899-2011) / Object labels from the exhibition". Agnes Weinrich (1873-1946) Musical Abstraction, n.d. Oil on board, Private Collection. Traditional Fine Arts Organization, Inc. 2012. Retrieved 2014-05-24.

Further reading

- Agnes Weinrich, 1873-1946, by Louise R Noun and Deborah Leveton (a catalog accompanying an exhibition held at the Des Moines Art Center; Art Guild of Burlington; and Provincetown Art Association & Museum, 30 p., ill., ports., 26 cm. (Des Moines, Iowa, Des Moines Art Center, 1997).

- "Agnes Weinrich," by Louise R. Noun, Woman's Art Journal, Autumn 1995-Winter 1996 (Rutgers University, Rutgers, N.J., 1996)

- Art in Narrow Streets, by Ross Moffett, (Provincetown, Pilgrim Memorial Association, 1989).

- Iowa artists of the first hundred years, by Zenobia Brumbaugh Ness and Louise Orwig (Des Moines, Iowa, Wallace-Homestead Co., 1939)