Aero L-29 Delfín

The Aero L-29 Delfín (English: Dolphin, NATO reporting name: Maya) is a military jet trainer developed and manufactured by Czechoslovakian aviation manufacturer Aero Vodochody. It is the country's first locally designed and constructed jet aircraft, as well as likely being the biggest aircraft industrial programme to take place in any of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) countries except the Soviet Union.[2]

| L-29 Delfín | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Aero L-29 Delfín | |

| Role | Military trainer aircraft Light attack |

| Manufacturer | Aero Vodochody |

| Designer | Ing. Jan Vlček, Z. Rublič and K. Tomáš[1] |

| First flight | 5 April 1959 |

| Introduction | 1961 |

| Status | Limited service; popular civilian warbird |

| Primary users | Soviet Air Force (historical) Czechoslovak Air Force (historical) Bulgarian Air Force (historical) Egyptian Air Force (historical) |

| Produced | 1963–1974 |

| Number built | 3,665[1] |

In response to a sizable requirement for a common jet-propelled trainer to be adopted across the diverse nations of the Eastern Bloc, Aero decided to embark upon their own design project with a view to suitably satisfying this demand. On 5 April 1959, an initial prototype, designated as the XL-29, performed its maiden flight. The L-29 was selected to become the standard trainer for the air forces of Warsaw Pact nations, for which it was delivered from the 1960s onwards. During the early 1970s, the type was succeeded in the principal trainer role by another Aero-built aircraft, the L-39 Albatros, heavily contributing to a decline in demand for the earlier L-29 and the end of its production during 1974.[3]

During the course of the programme, in excess of 3,000 L-29 Delfin trainers were produced. Of these, around 2,000 were reported to have been delivered to the Soviet Union, where it was used as the standard trainer for the Soviet Air Force. Of the others, which included both armed and unarmed models, many aircraft were delivered to the various COMECON countries while others were exported to various overseas nations, including Egypt, Syria, Indonesia, Nigeria and Uganda.[2] Reportedly, the L-29 has been used in active combat during several instances, perhaps the most high-profile being the use of Nigerian aircraft during the Nigerian Civil War of the late 1960s and of Egyptian L-29s against Israeli tanks during the brief Yom Kippur War of 1973.

Development

In the late 1950s, the Soviet Air Force commenced a search for a suitable jet-powered replacement for its fleet of piston-engined trainers; over time, this requirement was progressively broadened towards the goal of developing a trainer aircraft that could be adopted and in widespread use throughout the national air forces of the Eastern Bloc countries. Around the same time, the nation of Czechoslovakia had also been independently developing its own requirements for a suitable jet successor to its current propeller-powered trainer aircraft.[1] In response to these demands, Aero decided to develop its own aircraft design; the effort was headed by a pair of aerospace engineers, Z. Rublič and K. Tomáš.[1] Their work was centered upon the desire to produce a single design that would be suitable both performing basic and advanced levels of the training regime, carrying pilots straight through to being prepared to operate frontline combat aircraft.[4]

The basic design concept was to produce a straightforward, easy-to-build and operate aircraft. Accordingly, both simplicity and ruggedness were stressed in the development process, leading to the adoption of manual flight controls, large flaps, and the incorporation of perforated airbrakes positioned on the fuselage sides. Aerodynamically, the L-29 was intentionally designed to possess stable and docile flight characteristics; this decision contributed to an enviable safety record for the type. The sturdy L-29 was able to operate under austere conditions, including performing take-offs from grass, sand or unprepared fields.[4] On 5 April 1959, the prototype XL-29 conducted its maiden flight, powered by a British Bristol Siddeley Viper turbojet engine.[2][4] The second prototype, which flew shortly thereafter, was instead powered by the Czech-designed M701 engine. The M-701 engine which was used in all subsequent aircraft.

During 1961, a small pre-production batch of L-29s were evaluated against the Polish PZL TS-11 Iskra and the Russian Yakovlev Yak-30, the main rival submissions for the Warsaw Pact's standardised trainer. Shortly after the completion of the fly-offs, it was announced that the L-29 had been selected as the winner; according to aviation author John C. Fredrikson, this outcome had been highly unexpected and surprising to several observers.[1] Regardless of the result, Poland chose to continue to pursue the development and procurement of the TS-11; however, all of the other Warsaw Pact countries decided to adopt the Delfin under the agreements of COMECON.

During April 1963, full-scale production of the L-29 commenced; 3,600 aircraft were manufactured over a production run of 11 years. During its production life, several derivatives of the L-29 were developed, such as a dedicated, single-seat, aerobatic version, which was designated as the L-29A Akrobat. Another model, an armed reconnaissance version complete with multiple downwards-looking cameras installed in the rear cockpit position, referred to as the L-29R, was also under development; however, during 1965, the L-29R project was terminated.[4] Optional armaments could be installed upon some models, consisting of either a detachable gun pod or a pod containing up to four unguided missiles, which could be set upon hardpoints underneath each wing.

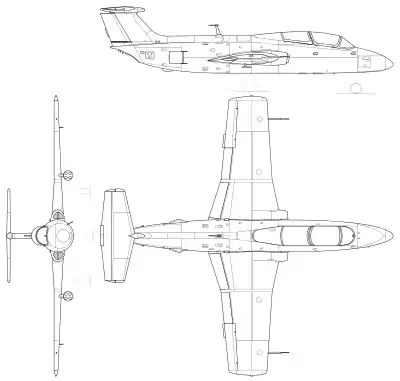

Design

The Aero L-29 Delfín was a jet-powered trainer aircraft, known for its straightforward and simplistic design and construction. In terms of its basic configuration, it used a mid-wing matched with a T-tail arrangement; the wings were unswept and accommodated air intakes for the engines within the wing roots. The undercarriage was reinforced and capable of withstanding considerable stresses. According to Fredriksen, the L-29 was relatively underpowered, yet exhibited several favourable characteristics in its flight performance, such as its ease of handling.[1] The primary flying controls are manually operated; both the flaps and airbrakes were actuated via hydraulic systems.[5]

Production aircraft were powered by the Czech-designed Motorlet M-701 turbojet engine, which was capable of generating up to 1,960lbf of thrust. Between 1961 and 1968, approximately 9,250 engines were completed; according to reports, no fewer than 5,000 of these engines were manufactured in support of the Delfin programme.[2][6] The student pilot and their instructor were placed in a tandem seating layout underneath separate canopies, the instructor being placed in a slightly elevated position to better oversee the student. Both the student and instructor were provisioned with ejection seats; these were intentionally interlinked to fire in a synchronised manner if either seat was deployed as to eliminate any possibility of a mid-air collision between the two ejector seats occurring.[1][4]

During their late life, many L-29s were resold onto private operators and have seen use in the civil sector.[5] It has become common for various modifications to be carried out to convert the type for such use; these changes would commonly include the removal of military-orientated equipment (such as the gun sight), the replacement of the metric altimeters with Western counterparts, the addition of alternative radio systems, and new ejection seats. It was also routine for several subsystems, such as the oxygen system, to be disabled rather than removed.[5]

Operational history

In excess of 2,000 L-29 Delfins were ultimately supplied to the Soviet Air Force. Like the majority of Soviet-operated aircraft, it acquired its own NATO reporting name, "Maya."[4] In the trainer role, the L-29 enabled air forces to adopt an "all-through" training regime using only jet-powered aircraft, entirely replacing earlier piston-engined types.

The Delfin served in basic, intermediate and weapons training roles. For this latter mission, they were equipped with hardpoints to carry gunpods, bombs or rockets; according to Fredrikson, the L-29 functioned as a relatively good ground-attack aircraft when deployed as such.[1] It saw several uses in this active combat role, such as when a number of Egyptian L-29s were dispatched on attack missions against Israeli ground forces during the Yom Kippur War of 1973. The type was also used in anger during the Nigerian Civil War of the late 1960s.[1] On 16 July 1975, a Czechoslovak Air Force L-29 reportedly shot down a Polish civilian biplane piloted by Dionizy Bielański, who had been attempting to defect to the West.[7]

The L-29 was supplanted in the inventory of many of its operators by the Aero L-39 Albatros.[4] The L-29 which was commonly used alongside the newer L-39 for a time. The type was used extensively to conduct ground attack missions in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War by Azeri forces. At least 14 were shot down by Armenian air-defences, out of the total inventory of 18 L-29s; the Azeri Air Force lost large amounts of its air force due to anti aircraft fire.[8]

On 2 October 2007, an unmodified L-29 was used for the world's first jet flight powered solely by 100 per cent biodiesel fuel. Pilots Carol Sugars and Douglas Rodante flew their Delphin Jet from Stead Airport, Reno, Nevada to Leesburg International Airport, Leesburg, Florida in order to promote environmentally friendly fuels in aviation.[9]

The L-29, much like its L-39 successor, has found use in air racing, some of which have been re-engined with the British Armstrong Siddeley Viper turbojet engine.[10][11] From 10 September to 14 September 2008, a pair of L-29s took first and second place at the Reno Air Races. Both L-29s consistently posted laps at or above 500 miles per hour; former Astronaut Curt Brown took first place in "Viper," followed by Red Bull racer Mike Mangold in "Euroburner."[12]

Russia has claimed that it destroyed a pair of Georgian L-29s during the 2008 South Ossetia war.[13] On 18 January 2015, separatist forces in the War in Donbass claimed that they possessed an operational L-29.[14]

Operators

Current military operators

.jpg.webp)

Angola

Angola- National Air Force of Angola – 6 L-29s were in service as of December 2016.[15]

Georgia

Georgia- Army Air Section - 4 L-29s were in service as of December 2016.[15]

Former military operators

Afghanistan

Afghanistan- The Afghan Air Force operated as many as 24 from 1978 to as late as 1999.

Armenia

Armenia- The Armenian Air Force

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan- The Azerbaijani Air and Air Defence Force

Bulgaria

Bulgaria- Bulgarian Air Force operated 102 examples, delivered between 1963–1974, retired from service in 2002.

Czech Republic

Czech Republic- Czech Air Force[16]

.jpg.webp)

People's Republic of China

People's Republic of China- PLAAF got 4 L-29s in 1968.

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia- The Czechoslovak Air Force

East Germany

East Germany- East German Air Force

Egypt

Egypt- Egyptian Air Force[17] – withdrawn

Ghana

Ghana- Ghana Air Force[18]

Guinea

Guinea- Military of Guinea[19]

Hungary

Hungary- Hungarian Air Force

Indonesia

Indonesia- Indonesian Air Force[20]

Iraq

Iraq- Iraqi Air Force – Received 78 L-29s between 1968 and 1974. A number were converted to Unmanned aerial vehicles in the 1990s.[21] No longer operated

Libya

Libya- Libyan Arab Republic Air Force 20 L29s recorded lost in 1987 during the final stages of the Chadian–Libyan conflict[22]

Mali

Mali- Air Force of Mali – 6 in service as of December 2012.[23]

Nigeria

Nigeria- Nigerian Air Force

Romania

Romania- Romanian Air Force[24] – all the L-29 have been retired in 2006

Slovakia

Slovakia- Slovak Air Force – after dissolution of Czechoslovakia, 16 L-29 were given to newly independent Slovak Air Force.[25] They were withdrawn in 2003.

Syria

Syria- Syrian Air Force[26]

Uganda

Uganda- Ugandan Air Force[27]

Ukraine

Ukraine- Ukrainian Air Force[28]

Vietnam

Vietnam- Vietnam People's Air Force

United States

United States- United States Navy[29]

Soviet Union

Soviet Union- operated as many as 2,000

Civilian operators

- One private L-29, with experimental registration LV-X468. Registered in Uruguay as CX-LVN in 2011–12.

- One private L-29C, VH-BQJ. Based near Sydney, New South Wales.

- Private L-29C, OK-ATS, Czech Jet Team Žatec – Macerka.[30] Plane crashed on 10 June 2012, killing pilot and passenger.

- Private L-29, OK-AJW, Blue Sky Service Brno – Tuřany [31]

.svg.png.webp) Canada

Canada- Private L-29, powered by a Viper engine bringing up to 70% increase in thrust over the original stock engine, operated by WATERLOO WARBIRDS to deliver flight experiences to the public

- Private L-29, C-FLVB, operated by International Test Pilots School, Canada as a Flight Test Training tool.[32]

- Two private L-29s, operated by the ACER Cold War Museum. Ex-Bulgarian Air Force.[33]

- One L-29C, OY-LSD owned by Lasse Rungholm, Niels Egelund (until 31.12.2015), Claus Brøgger and Kåre Selvejer.[34]

- L-29 ZK-JET operated on commercial joyflights by Double X Aviation, Queenstown Airport

- L-29 ZK-SSU and ZK-VAU operated by Soviet Star from Christchurch International Airport.[35]

- Three L-29C, LN-RWN, LN-ADA and LN-KJJ, operated by Russian Warbirds of Norway (www.warbird.no). ADA and KJJ was both destroyed in 2016 in a big hangar fire.

- One civilian L-29 and one L-29 Viper operated by Feniks Aeroclub outside Moscow[36]

- Several L-29s operated by DOSAAF.

- One private L-29C, OM-JET, owned by Ján Slota[37]

- One L-29, OM-JLP is owned by Slovtepmont Inc. [38]

- Cpt. Jozef Vaško and col. Radomil Peca in retirement are owners of one L-29, OM-SLK [39]

- Two Sasol Tigers aerobatic team flying the L-29.

- University of Iowa Operator Performance Laboratory. Used as high dynamics flight research aircraft for development of pilot state characterization [40]

- One L-29, N29CZ, is operated by World Heritage Air Museum, in Detroit, Michigan.[41]

- One as an avionics high dynamics flight test aircraft at the Ohio University Avionics Engineering Center [42]

- One L-29C, N61300, is operated by DK Aviation Services, in Dallas Texas.

Accidents

- On 18 August 2000, a privately owned L-29 was destroyed after it impacted with the water during an aerobatic display at the Eastbourne Airbourne Air Show, at Eastbourne, East Sussex. The pilot, a former member of the Royal Air Force's (RAF) Red Arrows display team, was killed with no visible signs of attempting to eject from the aircraft.[5]

Specifications (L-29)

Data from Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1971–72,[43]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Length: 10.81 m (35 ft 6 in)

- Wingspan: 10.29 m (33 ft 9 in)

- Height: 3.13 m (10 ft 3 in)

- Wing area: 19.80 m2 (213.1 sq ft)

- Aspect ratio: 5.36:1

- Airfoil: NACA632A217 at root, NACA 642A212 at tip

- Empty weight: 2,280 kg (5,027 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 3,280 kg (7,231 lb)

- Fuel capacity: 962 L (254 US gal; 212 imp gal), provision for 2× 150 L (40 US gal; 33 imp gal) external tanks

- Powerplant: 1 × Motorlet M-701c 500 turbojet, 8.7 kN (1,960 lbf) thrust

Performance

- Maximum speed: 655 km/h (407 mph, 354 kn) at 5,000 m (16,400 ft)

- Stall speed: 130 km/h (81 mph, 70 kn) (flaps down)

- Never exceed speed: 820 km/h (510 mph, 440 kn)

- Range: 894 km (556 mi, 483 nmi) (with external tanks)

- Endurance: 2 hr 30 min

- Service ceiling: 11,000 m (36,000 ft)

- Rate of climb: 14.00 m/s (2,755 ft/min)

Armament

- Guns: 2x 7.62mm machine gun pods on hardpoints

- Hardpoints: 2

- Rockets: 8× air-to-ground rockets

- Bombs: 2× 100 kg (220 lb) bombs

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

References

Citations

- Fredriksen 2001, p. 4.

- "Selling to Eastern Europe." Archived 2017-10-28 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 13 June 1974. p. 174.

- "Prowling with Bob Lutz." Archived 2017-10-28 at the Wayback Machine Flying Magazine, October 1996. p. 67.

- "L-29 DELFÍN." Archived 2017-10-29 at the Wayback Machine army.cz, Retrieved: 28 October 2017.

- "AAIB Bulletin No: 3/2001: Aerovodochody L29 Delfin, G-MAYA." Archived 2017-02-05 at the Wayback Machine Air Accidents Investigation Branch, Retrieved: 28 October 2017.

- "History." Archived 2017-10-29 at the Wayback Machine GE Aviation, Retrieved: 28 October 2017.

- Cameron, Robert. "New facts emerge about 1975 downing of Polish aircraft." Archived 2009-04-18 at the Wayback Machine Czech Radio, 14 April 2009.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-06-04. Retrieved 2011-02-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Biello, David. "Biodiesel Takes to the Sky." Archived 2011-03-19 at the Wayback Machine Scientific American, 30 November 2007.

- "PRS – What it is like." Archived 2017-10-29 at the Wayback Machine racingjets.com, 22 June 2017.

- "National Championship Air Races 2016 Jet Qualifiers." Archived 2017-10-29 at the Wayback Machine airrace.org, Retrieved: 28 October 2017.

- Gibson, Robert “Hoot”. "2008 Reno Air Races." Archived 2017-10-29 at the Wayback Machine Plane & Pilot, 16 December 2008.

- Pike, John. "Georgia Air Force". www.globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 2009-05-15. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-08-13. Retrieved 2015-01-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "World Air Forces 2017". Flightglobal Insight. 2016. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- Flight International 16–22 November 2004, pp. 53–54.

- Flight International 16–22 November 2004, p. 56.

- Flight International 16–22 November 2004, p. 59.

- Flight International 16–22 November 2004, p. 62.

- "INDONESIA PURCHASES NEW JET TRAINERS FROM CZECHOSLOVAKIA | CIA FOIA (foia.cia.gov)". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-08-09. Retrieved 2018-08-09.

- Vala Aviation News May 2003, pp. 355–357.

- K. Pollack, Arabs at War, Chapter 4.

- Hoyle Flight International 11–17 December 2012, p. 55.

- Flight International 16–22 November 2004, pp. 81–82.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Flight International 16–22 November 2004, p. 88.

- Rodney Muhumuza (15 July 2007). "Force Commander Tells His Life Under Amin". Daily Monitor. Kampala. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Flight International 16–22 November 2004, pp. 91–92.

- "Naval Air: Cruise Missile Pretenders". www.strategypage.com. Archived from the original on 2010-07-01. Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-06-03. Retrieved 2008-11-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Aircraft – ITPS Canada". Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- "Our Aircraft." Archived 2017-12-15 at the Wayback Machine ACM Warbirds of Canada.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2012-01-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-13. Retrieved 2015-01-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-09-24. Retrieved 2016-09-23.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-05-31. Retrieved 2009-05-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-03-05. Retrieved 2017-03-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-03-05. Retrieved 2017-03-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Operator Performance Laboratory." Archived 2010-11-13 at the Wayback Machine College of Engineering, University of Iowa. Retrieved: 19 June 2017.

- "Aero Vodochody L29." Archived 2018-12-15 at the Wayback Machine World Heritage Air Museum. Retrieved: 19 June 2017.

- "Delfin L-29." Archived 2018-12-15 at the Wayback Machine Russ College of Engineering and Technology, Ohio University. Retrieved: 19 June 2017.

- Taylor 1971, p. 29.

Bibliography

- Fredriksen, John C. International Warbirds: An Illustrated Guide to World Military Aircraft, 1914–2000. ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1-576-07364-5.

- Gunston, Bill, ed. "Aero L-29 Delfin." The Encyclopedia of World Air Power. New York: Crescent Books, 1990. ISBN 0-517-53754-0.

- Hoyle, Craig. "World Air Forces Directory". Flight International. Vol. 180, No. 5321. 13–19 December 2011. pp. 26–52. ISSN 0015-3710.

- Hoyle, Craig. "World Air Forces Directory". Flight International. Vol. 182, No. 5370. 11–17 December 2012. pp. 40–64. ISSN 0015-3710.

- Hoyle, Craig. "World Air Forces Directory". Flight International. Vol. 188, No. 5517. 8–14 December 2015. pp. 26–53. ISSN 0015-3710.

- Taylor, John W. R. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1971–72. London:Jane's Yearbooks,1971. ISBN 0-354-00094-2.

- Vala, Vojtec. "Saddam's Deadly Drones". Aviation News. Vol 65, No, 5. May 2003. pp. 355–357.

- "World Air Forces 2004" Flight International. Vol. 166, No. 4960. 16–22 November 2004. pp. 41–100. ISSN 0015-3710.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aero L-29. |

- (1961) Aero L-29 Delfin Flight Manual

- Czech Jet Team — civilian display team.

- Aircraft.co.za – The Complete Aviation Reference

- Warbird Alley L-29 Page

- Gauntlet Warbirds — L-29 Training in the Chicago Area

- Walkaround L-29 Delfin from Poltava

- Walkaround L-29 Delfin from Yegoryevsk

- Walkaround L-29 Delfin from Zaporozhye

- Soviet Star, Christchurch, New Zealand

- Double X Aviation Ltd, Queenstown, New Zealand