Administrative law in Mongolia

Administrative law in Mongolia is the body of law that governs the activities of administrative agencies of the Mongolian government. These activities include rulemaking, adjudication, or the enforcement of a specific regulatory agenda.

| Mongolian Laws | |

|---|---|

| Constitution of Mongolia Mongolian nationality law Administrative law in Mongolia LGBT rights in Mongolia | |

| Mongolia | |

<div-align="center"> |

| Administrative law |

|---|

| General principles |

|

Administrative law in common law jurisdictions |

|

Administrative law in civil law jurisdictions |

| Related topics |

History of administrative law

Administrative law in Mongolia developed as the country transited from the Soviet-era to a democratic state. The development can be divided into two main stages.

Soviet-era

During the Soviet-era:

- Three central agencies of state administration were formed.[1]

- The Mongolian People's Government became the highest agency of state power, with the powers to implement reforms in law, ministries and judiciary. (Primacy of the one-party State upheld.)[1]

Post Soviet-era

After democratisation:

- Major reforms of administrative structures and practices of government agencies as part of the transition into a market economy[2]

- Founded the Management Development Program (MDP) in 1994 with the support of United Nations to implement more extensive reforms in[2]

- Public administration and civil service

- Decentralization and local administration strengthening

- Private sector development

- The formation of administrative courts.[3]

- Substantial reduction of the President's power in deference to Parliament, the Cabinet and the Law on the Presidency.[3]

- Greater autonomy for local administration on the principle of ‘self-government and central guidance’.[3]

- Executive power circumscribed by the Constitution, which in turn is enforced by a newly established Constitutional Tsets (Court).[3]

Further progression:

- Rapid implementation of MDP reforms initially, but progress soon stalled[2]

- United Nations adapted the New Zealand model of administrative reforms for Mongolia which served to further eliminate conflict of interests in the restructuring of administrative units.[2]

Sources of law in Mongolia

Constitution

The Constitution is the supreme source of law in Mongolia. Influenced by the Romano-Germanic civil law system, Mongolia recognizes written law as the main source of law. The Constitution in 1992 abolished Marxism-Leninist ideology and laid out the democratic principles of the separation of state powers and the fundamental rights of citizens.[4]

Statutes

Statutes are a primary source of law. There is an accepted distinction between normative acts (which regulates conventional social behavior) and non-normative acts.[5] The hierarchy of state agencies is a factor that determines which agency will govern which act. Only the legislative branch of the government has the right to make laws.[5]

Legal Customs

Mongolia's nomadic past and unique living habits has elevated the importance of customs as a source of law. Throughout generations, customs that complement existing legal norms have prevailed. However, as there is lack of substantial evidence in literature, it is uncertain if Mongolian courts will recognize customs in the absence of legislation.[5]

International Law

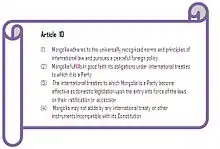

The position of international law as a source of law in Mongolia was elevated following the 1992 Constitution of Mongolia.[6] According to Art 10(3) of the Constitution, international treaties to which Mongolia is a party eventually becomes domestic law, unless they contradict the Constitution itself.[4]

Areas of administrative rulemaking

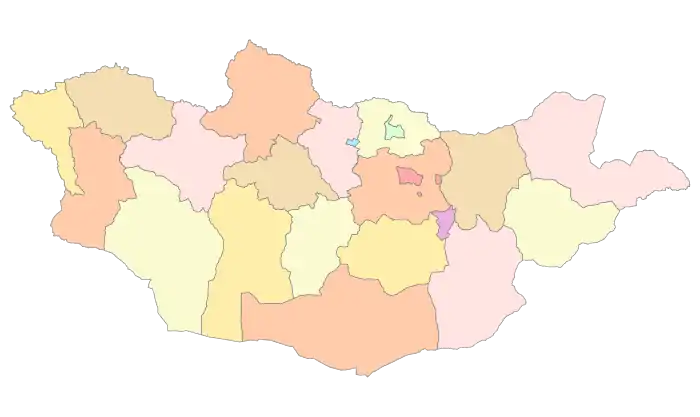

Mongolia is divided administratively into 21 aimags (provinces) according to Article 57 of the Constitution.[7] The Constitution vests the governor and parliament of the provinces with self-administrative powers.[7]

The Government of Mongolia is vested with the executive power of Mongolia[7] and is composed of Ministries[7] under the direction of the Cabinet and the Prime Minister. The roles, duties and responsibilities of these government agencies are usually defined by codified statutes.

The following lists the ministries within the Government with significant existing bodies of regulations:

Ministry of Mineral Resources

With respect to mining activity in Mongolia,[8] the Ministry of Mineral Resources and Energy, their subsidiary government and the local aimag government have responsibilities regulated by the Mineral Laws of Mongolia.[9] For instance, the local administrative body of an aimag has a duty to monitor compliance with respect to environmental reclamation, health and safety regulations under Article 12 of the Mineral Laws.[9]

Ministry of Environment

The duties and powers of the Ministry of Environment in Mongolia are largely governed by the Environmental Protection Law of Mongolia.[10] Furthermore, other laws such as the Law of Mongolia on Land also empower the land departments of individual aimags in the enforcement of the land laws of Mongolia.[11]

General Customs Office

The General Customs Office of Mongolia and their State Customs Inspectors have to abide by the Customs Law of Mongolia[12] when they enforce customs laws. In addition, they are also empowered to impose tariffs on goods under the Customs Tariff Law of Mongolia.[13]

Nuclear Energy Agency

The Nuclear Energy Agency is also bound by the Law of Mongolia on its nuclear-weapon-free status, to only use nuclear energy for non-military purposes.[14]

Ministry of Education

The Ministry of Education has recently reformed its laws. In 2000, due to budget deficiencies, Mongolian schools were reported to have resorted to child labour to generate income.[15] These problems were finally addressed by the 2002 Education Law, in which the government finally re-centralised educational finance in the form of the 'single treasury' measure.

Ministry of Justice and Home Affairs

Police laws were adopted in 1994 and were implemented to UN standards. The Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials and the Basic Principles for the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials are the body of regulations governing all law enforcement officers.[16]

National Human Rights Commission

The National Human Rights Commission of Mongolia Act was enacted to empower and regulate the administrative functions of the National Human Rights Commission. Thereafter, the Commission was established by a State Great Khural resolution on 11 January 2001.[17] The Act empowers the Commission with the power to investigate complaints with regards to violations of human rights,[18] amongst others.

Process of regulatory rulemaking and discretion of regulators

Legislature's role

The 1992 Constitution of Mongolia introduced a parliamentary system. Laws are made by a unicameral legislature known as the State Great Khural comprising 76 members representing 26 multi-member constituencies who are elected by bloc vote for a term of 4 years.

External input is sought by the legislature to ensure greater inclusiveness in decision-making. Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and Community-Based Organizations (CBOs) can participate in the law-making process by joining a group to aid in the drafting of a specific law, or by special invitation (fairly rare). In 2007, a CBO coalition proposed amendments to the law-making process which have been tabled in Parliament. The ‘citizens’ hall’ process was initiated in 2009 to facilitate the public's input into the law-making process.

These efforts also extend to ensuring transparency in executive action. In 2009, a parliamentary working group on the mineral sector was set up in an effort to ensure that Mongolia does not repeat the mistakes of other resource-rich countries in its mining program and that expansion of the mining sector adheres to principles of transparency.[19]

Executive's role

The Executive comprises the Prime Minister and his Cabinet, appointed by the President, a ceremonial head of state. The Executive enforces the laws made by the Legislature and can create subsidiary legislation to that end.

The Executive too has taken steps to ensure transparency. Mongolia's National Legal Institute (NLI), which is affiliated with the Ministry of Home Affairs and Justice, makes all approved legislation available online. The NLI also inputs into the legislative process by researching existing and proposed laws and by introducing new laws to the general public. The NLI also cooperates with the Mongolian parliament by exchanging information directly with the parliamentary research center. This ensures that citizens are aware of the laws they are subjected to and reflects transparency of rule-making to the Mongolian public.

Executive action in Mongolia is also bound by international conventions to which it is a signatory. This is stipulated in Article 10(3) of the Mongolian Constitution. 160 out of the 373 laws in force in Mongolia included provisions stating that should they conflict with international treaties, the treaties will take precedence.[20]

Executive power can also be subjected to judicial review, as will be discussed below.

Process for private challenges to government actions and rules

Judicial review of administrative action

Individuals may challenge executive acts through a process known as judicial review.

Case Study

In one example of an action involving judicial review of administrative action in 2005,[21] an application for a mining license by a mining company was discussed at a local hural (legislature) of a soum (district)[22] and most of those present were opposed to the application. However, the Praesidium (executive head of the soum) approved of the application and the mining company then obtained a license from the central government. Despite protests from leaders of the hural, the Praesidium issued a decision that the company had the right to proceed under its license. The leaders of the hural subsequently appealed to the Arkhangai Province Administrative Court. The court held that:

- the Praesidium had no authority to overrule the hural;

- the mining company's license was invalid;

- if the river were damaged by mining activities, the families in the valley would not be able to sustain their herds and would have to move to the city; and

- it called for more transparency in licensing procedures by the soum executive.

Process of judicial review

Step 1: A complainant must submit his complaint against a government action within 30 days under the statute of limitation.[23]

Step 2: A pre-hearing is conducted by the Administrative Tribunal before the complaint is allowed to proceed to the administrative courts. At the hearing, a direct supervising officer decides on the legality of the government action.[23]

Step 3: Parties not in favour of the outcome of the pre-hearing are allowed to file an appeal to the administrative courts.[23] Step 4: The administrative courts are to allow commencement of the action within 7 days upon receiving the claim.[23]

Step 5: A court official delivers the summons to the defendant.[23]

Step 6: In court, the judge or his law clerk would submit the copy of claim, attached materials, and inform the defendant of his rights.[23]

Step 7: When a claim is accepted by the court, the judge invites the defendant to a meeting to determine whether there is a valid defense. If a settlement is not reached, a date is allocated for the hearing and it must be held within 75 days (for the Capital City Administrative Court) or 85 days (for provincial administrative courts) after filing.[23]

Step 8: A public trial is held. All evidence is presented and examined at the hearing and the court secretary makes a full transcript.[23] Step 9: Decisions are made in the “conference room” after hearing the opinion/comment of the citizen representatives. If there is more than one judge on the bench, the decision is made by majority vote.[23]

Analysis and assessment of current rules

Current standard of administrative laws

Administrative laws in Mongolia have acceptable standards of transparency and clarity, with 160 of the 373 laws in Mongolia being international laws incorporated through the signing of treaties.[24] For example, most of Mongolia's police law (especially the regulations governing the use of force and firearms) adheres to specific UN standards.[25] For local laws, the Executive has also taken steps to ensure transparency in the rule-making process. However, the transplantation of international standards into the local social climate is insufficient in eradicating unlawful executive behaviour. For example, the detection and prosecution of corrupt police officers remains unsatisfactory due to the lack of an open procedural reporting system within the police force. In addition, the detention and prison system in Mongolia faces a huge lack of financial resources, giving rise to low inmate living conditions that are incompatible with the law.[26] It can thus be seen that though the letter of administrative law is fundamentally sound, its enforcement needs to be strengthened.

State of judicial review

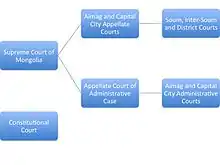

The establishment of administrative courts signified a marked progress in the judicial system of Mongolia as well as the increasing emphasis that the country is placing on protecting individual rights against unlawful governmental action. Nevertheless, the nascent development of administrative law in Mongolia has naturally invited a fair share of controversy and criticism over the role of the administrative courts in judicial review.

Executive non-compliance with judicial decisions

In a study conducted by Brent T. White[27] in his article,[28] 50% of experts surveyed disagreed with the statement, “Court decisions are respected and enforced by other branches of government.” These experts also indicated that the executive branch often does not honour court decisions with which it disagrees. One expert even indicated that tax inspectors feel free to ignore decisions by the courts when they believe the courts’ interpretation to be wrong.[29]

Executive interference with the judiciary

In the same study, only 19% of the experts surveyed agreed that “Court decisions are free from political influence from other branches of government or public officials.” These experts shared the views that high-ranking government officials, including the President, exert considerable influence over the courts, especially where the personal, political or business interests of the governments are at stake.

Conflicts with the Constitutional Tsets (Court)

A recent conflict between the administrative courts and the Constitutional Tsets arose in 2004-2005 when the Capital City Administrative Court ruled in favour of the plaintiffs in two landmark cases.[30] An action was then filed in the Constitutional Tsets asserting the unconstitutionality of Article 4.1.1 of the Law on Administrative Procedure, which lists the government offices and ministries which may be named as defendants in an administrative action. In Enkhbayar v Parliament,[31] the Tsets found Article 4.1.1 to be unconstitutional and accordingly directed Parliament to amend the Law on Administrative Procedure. Such an incident exemplifies the tension in the duty of the administrative courts in controlling the acts of the Executive and the Constitutional Tsets in protecting the Constitution as the supreme law of the land.

In a written article,[23] Tsogt Tsend, presently a Chief Judge in the Administrative Court of Appeals has nonetheless expressed two reasons for underscoring his support of the setting up of separate administrative courts despite the concern of jurisdictional overlapping with the Constitutional Tsets. The first is the specialized nature of the administrative courts which serves as a focal point for the development of Mongolian administrative law. The second is aggrieved claimants being given provision of access to judges highly trained in the field of administrative law. This will hopefully increase public confidence in the administrative courts and encourage attorneys to take the fight against illegal administrative action to a new level.

Comparison with other countries

Like most civil law systems, such as Kazakhstan and Germany, Mongolia has specialized administrative courts[7] with exclusive power to hear judicial reviews. In contrast, in common-law countries like England and Singapore, judicial review actions are heard in a court of general jurisdiction like the High Court.[32]

In addition, the powers of the administrative courts are derived from a codified statute called the Law on Administrative Procedure. This ensures certainty, reliability and legitimacy. In common law courts, (e.g. in England) judicial review is developed through case law and is not a power granted by statute, a result of which people have questioned the legitimacy of this process.[32]

See also

References

- Butler, William (1982), The Mongolian Legal System (Studies on Socialist Legal Systems), Springer, ISBN 978-90-247-2685-1

- Nixson, Frederick I.; Walters, Bernard (1999), Administrative Reform and Economic Development in Mongolia, 1990-1997: A Critical Perspective, Review of Policy Research, 1999, vol. 16, pp. 147–175, doi:10.1111/j.1541-1338.1999.tb00873.x, ISBN 978-90-247-2685-1 url to full text restricted to subscribers

- Sanders, Alan J.K. (1992), "Mongolia's New Constitution: Blueprint for Democracy", Asian Survey, Asian Survey Vol. 32, No. 6 (Jun., 1992), 32 (6): 506–520, doi:10.1525/as.1992.32.6.00p0176y, ISBN 978-90-247-2685-1, JSTOR 2645157 url to full text restricted to JSTOR subscribers

- "Constitution of Mongolia, at WIPO

- Butler, William (1982), The Mongolian Legal System (Studies on Socialist Legal Systems), Springer, ISBN 978-90-247-2685-1

- Legislation, Mongolia Lexadin, The World Law Guide

- The Constitution of Mongolia

- "CIA World Factbook"

- "The Mineral Laws of Mongolia, Articles 9, 10, 11 and 12" Archived March 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Environmental Protection Law of Mongolia" Archived March 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Law of Mongolia on Land" Archived March 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- " Customs Law of Mongolia" Archived March 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- " Customs Tariff Law of Mongolia" Archived March 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Law of Mongolia on its nuclear-weapon-free status" Archived March 31, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Decentralization and Recentralization Reform in Mongolia: Tracing the Swing of the Pendulum

- " Application of the Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials" Archived January 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "About the National Human Rights Commission of Mongolia Act" Archived September 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "National Human Rights Commission of Mongolia Act"

- "Mongolia Mission Report – Parliamentary Network on World Bank"

- "Mongolia Laws-Child Rights Information Network"

- "Decision of the Administrative Court, Arkhangai Province, No.4 (May 2, 2005) (Jargalsaikhan J)"

- "A governmental sub-division of Mongolia with administrative powers"

- Tsend, Tsogt (2010), Judicial Procedure for Administrative Case in Mongolia, Social Science Research Network, SSRN 1695283 (one-click download available for pdf; File name: SSRN-id1695283. Size: 128K)

- "Child Rights Information Network"

- "UNODC and Nutrisystem Can Unite in a Battle Against Addiction" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-13. Retrieved 2011-09-03.

- "Susan V. Lawrence, "Mongolia: Issues for Congress" (14 June 2011)"

- Associate Professor of Law, University of Arizona, James E. Rogers College of Law

- "Rotten to the Core: Project Capture and the Failure of Judicial Reform in Mongolia" [2009] 4 East Asia Law Review 209

- Interview with Tsogt Natsagdorj, Partner, Bona Lex Law Firm, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (May 7, 2008)

- Erdenebat & Erdenebaatar v. Government of Mongolia (Capital City Admin. Ct 2005); Enkhbold v. General Election Committee (Capital City Admin. Ct 2004)

- Constitutional Tsets (2005)

- Nelken, David; Orucu, Esin (2007), Comparative Law: A Handbook, Hart Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84113-596-0

.jpg.webp)